The 1695 Linfen earthquake struck Shanxi Province in North China, Qing dynasty on May 18. Occurring at a shallow depth within the continental crust, the surface-wave magnitude 7.8 earthquake had a maximum intensity of XI on the China seismic intensity scale and Mercalli intensity scale. This devastating earthquake affected over 120 counties across eight provinces of modern-day China. An estimated 52,600 people died in the earthquake, although the death toll may have been 176,365.

| Local date | May 18, 1695 |

|---|---|

| Magnitude | Ms 7.8 |

| Epicenter | 36°00′N 111°30′E / 36.0°N 111.5°E [1] |

| Type | Intraplate |

| Areas affected | Shanxi, Qing Dynasty |

| Max. intensity | MMI XI (Extreme) |

| Landslides | Yes |

| Casualties | 52,600–176,365 dead |

Tectonic setting

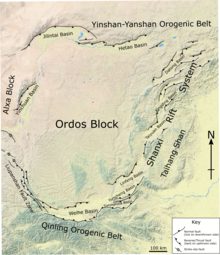

editThe Shanxi Rift System is a seismically active intracontinental rift zone in North China. Since 231 BC, eight Ms 7.0 earthquakes have been recorded in the rift system. The 1303 Hongdong and 1556 Shanxi earthquakes were the deadliest events occurring in the rift, with a death toll of 200,000 and 830,000, respectively.[2]

Bounded to the west by the Lüliang Mountains, and the east by the Taihang Mountains, the Shanxi Rift forms the eastern boundary of the Ordos Block; a fragment of continental crust within the Eurasian plate. Within the rift features half-grabens. It formed when extension began in the Miocene or Pliocene, separating the crust into the Ordos Block from the North China Craton. The reason for extension in this part of China is still debated though the most agreed hypothesis is crustal deformation resulting from the India-Asia collision involving the Indian and Eurasian plates along the Main Himalayan Thrust in the Himalayas, causing the rotation of crustal blocks in China. Other hypotheses are slab rollback of the Pacific plate as it subducts along the east coast of Japan; or localized intraplate tectonics.[3]

Dip-slip and strike-slip earthquakes in North China are consistent with ongoing crustal extension along the Shanxi Rift System. The rift extends for 1,200 km (750 mi), and is up to 60 km (37 mi) across. The graben is bounded by normal faults on both sides capable of generating earthquakes. Extension along the rift zone occur at a slow rate of 0.8 ± 0.3 mm (0.031 ± 0.012 in)/year, hence earthquakes occur with long intervals of recurrence. Previous estimated magnitudes of earthquakes by Chinese researchers have possible inaccuracies as they are biased on written descriptions and death toll from these earthquakes.[4]

Earthquake

editThe earthquake had an epicenter at Xiangfen County in the prefectural-level city of Linfen. The Linfen-Fushan Fault (also known as the Guojiazhuang Fault), Liucun Fault, and Luoyunshan Fault were determined to be sources of the event based on examining the seismic intensity from isoseismal maps. These individual faults were only capable of producing earthquakes with magnitudes up to 7.0, hence a multi-fault rupture was involved to produce a Ms 7.8 event.[5] It generated a 70 km (43 mi) rupture along a steeply-dipping northwest-striking fault with a left-lateral slip sense. The earthquake location is adjacent to another large earthquake in 1303. The previous event prior to 1695 was a Ms 7.0 earthquake in 1683. The 1695 earthquake occurred in a region of reduced stress due to coulomb stress transfer from previous events. The region was already under long-term stress which led to faults rupturing. The 1695 event is the most recent magnitude 7.0 or greater earthquake to occur in the Shanxi Rift.[2]

Damage and casualties

editAt Linfen, where the maximum intensity was X–XI, many dwelling in villages were destroyed, killing their inhabitants. The shock knocked down structures in the city, including walls, temples, towers, homes, and warehouses. According to one account, more than 40,000 homes were destroyed.[6] Conflagrations were started and the ground erupted black-colored water, killing many. More than 60 villagers died at a settlement in Linfen when temples and homes collapsed. In another village, more than 80 of the 180 inhabitants died due to collapsing structures. The shock collapsed entire cave homes and buried many people. In Xinjian Village, Xiangling County, 7,000 people died. Many more livestock were also killed. In the aftermath, only a handful of homes, government buildings, temples and education institutions survived. Linfen lost at least 28,000 residents or 16 percent of its population. The city accounted for 53 percent of the total death toll. Reports of damage also came from Hebei, Gansu, and Jiangsu provinces.[7] An official report in 1875 stated that 52,600 people died, but a monument from the Yuan dynasty placed that figure at 176,365.[8] Ground effects associated with the earthquake are still visible today. At Dongputou and Xiputou villages in the Xiangcheng District, a large valley, splitting villages into two. The Tongli canal, a source of water for agriculture in the region, was destroyed during the tremors.[9]

Response

editKangxi Emperor, the third emperor of the Qing dynasty, was briefed about the devastation. He appointed ministers and government officials to survey the affected area. A disaster relief team was dispatched to conduct rescue and relief efforts. Kangxi provided relief fund to help the victims of the earthquake and rebuild damaged cities.[5] Taels of silver were given to each deceased individual. In Linfen, a total of 36,212 taels were handled out. Donations requested by the Minister of Relief from all government officials amounted to 4,594,200 taels of silver and were used to rebuild homes. Funds for the reconstruction of towns and the city structure were allocated by the government. Soldiers patrolled the area to prevent crimes and disorderly conduct.[9]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ National Geophysical Data Center / World Data Service (NGDC/WDS) (1972), Significant Earthquake Database (Data Set), National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA, doi:10.7289/V5TD9V7K

- ^ a b Bin Li; Mathilde Bøttger Sørensen; Kuvvet Atakan (2015). "Coulomb stress evolution in the Shanxi rift system, North China, since 1303 associated with coseismic, post-seismic and interseismic deformation". Geophysical Journal International. 203 (3): 1642–1664. doi:10.1093/gji/ggv384. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ^ Bin Li; Kuvvet Atakan; Mathilde Bøttger Sørensen; Jens Havskov (2015). "Stress pattern of the Shanxi rift system, North China, inferred from the inversion of new focal mechanisms". Geophysical Journal International. 201 (2): 505–527. doi:10.1093/gji/ggv025.

- ^ Yueren Xu; Honglin He; Qidong Deng; Mark B. Allen; Haoyue Sun; Lisi Bi (2018). "The CE 1303 Hongdong earthquake and the Huoshan Piedmont Fault, Shanxi Graben: Implications for magnitude limits of normal fault earthquakes" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 123 (4): 3098–3121. Bibcode:2018JGRB..123.3098X. doi:10.1002/2017JB014928. S2CID 135046043.

- ^ a b Yan Xiao-bing; Zhou Yong-sheng; Li Zi-hong; Guo Jin. "1695年临汾73/4级地震发震构造研究" [A study on the seismogenic structure of Linfen M7¾ earthquake in 1695]. Dizhen Dizhi (in Chinese). 40 (4): 883–902.

- ^ "Ruins after the Earthquake in Linfen (1695)". kepu.net.cn. Science Museums of China. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ^ "A brief account of the Linfen earthquake in 1695". m.fx361.com. Archived from the original on 26 September 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ^ Pradeep Talwani (2015). "5". Intraplate Earthquakes (PDF). Cambridge University Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-12-15. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- ^ a b Wen Zhengye (31 March 2021). "康熙"抗震救灾"之山西临汾8.0级大地震 [Kangxi "Earthquake Relief" earthquake of magnitude 8.0 in Linfen, Shanxi]". Sohu (in Chinese). Retrieved 26 September 2021.