ʻIoane ʻŪkēkē, born ʻIoane Hohopa (c. 1830s – May 1, 1903), was a kumu hula (master or teacher of hula) and musical performer who organized hula performance during the Hawaiian Kingdom. He organized hula troupes for the court of King Kalākaua and accompanied his group's dances with the ʻūkēkē, a traditional Hawaiian string instrument, which gave him his nickname John or ʻIoane ʻŪkēkē. He was known for his flamboyant way of dress and dubbed the Hawaiian Dandy or Hawaiian Beau Brummel by the local English-language press.

ʻIoane ʻŪkēkē | |

|---|---|

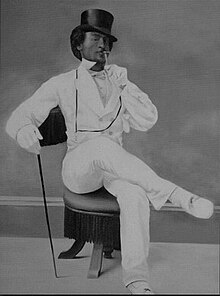

ʻIoane ʻŪkēkē dressed in his finest clothes | |

| Born | ʻIoane Hohopa c. 1830s |

| Died | May 1, 1903 |

| Resting place | Honolulu Catholic Cemetery |

| Nationality | Hawaiian Kingdom United States |

| Occupation(s) | kumu hula and musician |

| Spouse | Anna or Mary |

Life and career

editHe was born ʻIoane Hohopa in Hilo, on the island of Hawaii, around the 1830s. His obituary in The Hawaiian Star newspaper noted that he was over 70 years old when he died in 1903.[1][2] He was known variously as J. U. Smith, ʻIoane ʻŪkēkē, the Hawaiian Dandy, the Hawaiian Beau Brummel, and other variations of these names throughout his life.[1][3]

ʻIoane was a Hawaiian chanter and kumu hula, or master teacher, of hula who headed his own troupe of hula dancers, which included his wife and sister-in-law. He was noted for modernizing elements of the dance and accompanying his group's performance with music from his ʻūkēkē, a traditional Hawaiian string instrument, often described as a jew's harp. His skill at the ʻūkēkē gave him his nickname John or ʻIoane ʻŪkēkē.[4][5][6] His patrons included King Kalākaua and Princess Keʻelikōlani while "prominent people that wanted to entertain, besides court circles, would feel that things were amiss without the dandy and his jew’s-harp".[3][7]

Public performance of hula had been banned and heavily disparaged as heathen and lewd since the regency of Queen Kaʻahumanu due to the disapproval of the American Protestant missionaries. This changed during the reign of King Kalākaua (r. 1874–1891) who revived hula into cultural prominence.[8][9] During the coronation celebration of King Kalākaua in February 1883, ʻIoane and his troupe conducted public hula performances each night on the grounds of ʻIolani Palace. The festivities culminated in a grand luau at the palace, on February 26, which was attended by 5,000 people. The Pacific Commercial Advertiser, which gave a positive coverage the event of the luau, noted: "Dandy Ioane ... marshalled the performing girls in their short skirts and hula buskins, and accompanied their gyrations with his tremulous-toned instrument [a jew's-harp]."[10][11] The king was heavily criticized by his opponent and foreigners for sanctioning the public performance of hula, which had been banned since the days of the missionaries in Hawaii.[12][13]

ʻIoane was also renowned for his manner of dress and he was often seen on the streets of Honolulu with a velvet suit, jackets and slacks, white gloves, a cane, monocle and either a high silk hat or a beaver skin hat. Local English newspapers dubbed him the Hawaiian Dandy or the Hawaiian Beau Brummel.[14] He was often mistaken for a prince by visiting foreigners.[15][16] Lacking the financial means to purchase his fashionable wardrobe, he personally designed his own clothing, which his wife helped make, from donations made to him by his patrons and admirers. His image was later featured on a local brand of smoking tobacco.[3][17] Anthropologist Jane Desmond noted that ʻIoane's appearance and manner of dress in photographs "unusual, when compared with tourist representations, as an image of an obviously successful Native Hawaiian male."[18]

Personal life

editHis wife was named as Anna in his 1883 coverage in the Pacific Commercial Advertiser.[11] They raised a large family and she was described as "an industrious native wife" who "washed for many years for a living".[11] She and her sister were hula dancers in ʻIoane's troupe. Later sources called her Mary Kapule and her sister Anne Kapule.[19][20]

In later life, ʻIoane became blind. Impoverished, he resorted to playing his signature ʻūkēkē and begging for money on the streets of Honolulu. He died of old age, on May 1, 1903, at his residence on Punchbowl Street in Honolulu. He was buried at the Honolulu Catholic Cemetery.[1][2][17][21][22]

References

edit- ^ a b c The Hawaiian Star 4 May 1903

- ^ a b The Pacific Commercial Advertiser 3 May 1903

- ^ a b c The Honolulu Advertiser 20 January 1927

- ^ Kanahele 1979, pp. 66–67, 392–394.

- ^ Hopkins 1980, pp. 1–5.

- ^ Vaughan 2006, pp. 80–86.

- ^ Taylor 1935.

- ^ Imada 2012, pp. 12–13, 25.

- ^ The Pacific Commercial Advertiser 31 July 1880

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, p. 264.

- ^ a b c The Pacific Commercial Advertiser 27 February 1883

- ^ Ing 2019, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 265, 345.

- ^ The Pacific Commercial Advertiser 5 May 1903

- ^ Ka Nupepa Kuokoa 8 May 1903

- ^ Ke Aloha Aina 9 May 1903

- ^ a b The Pacific Commercial Advertiser 4 May 1903

- ^ Desmond 1999, p. 475.

- ^ Scott 1968, p. 183.

- ^ Desmond 1999, p. 474.

- ^ The Independent 4 May 1903

- ^ The Hawaiian Gazette 5 May 1903

Bibliography

editBooks and journals

edit- Desmond, Jane (1999). "Picturing Hawaiʻi: The "Ideal" Native and the Origins of Tourism, 1880–1915". Positions: East Asia Cultures Critique. 7 (2). Durham, NC: Duke University Press: 459–501. doi:10.1215/10679847-7-2-459. ISSN 1527-8271. OCLC 365413362. S2CID 144857781. Archived from the original on April 26, 2016. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- Hopkins, Jerry (February 1980). "Ioane ʻŪkēkē: Hawaiian Dandy, Hawaiian Tragedy". Haʻilono Mele. VI (2). Honolulu: The Hawaiian Music Foundation: 1–5.

- Imada, Adria L. (2012). Aloha America: Hula Circuits Through the U.S. Empire. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-9516-4. OCLC 806017785.

- Ing, Tiffany Lani (2019). Reclaiming Kalākaua: Nineteenth-Century Perspectives on a Hawaiian Sovereign. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-8156-6. OCLC 1085155006.

- Kanahele, George S. (1979). Hawaiian Music and Musicians: An Illustrated History. University Press of Hawaii. ISBN 978-0-8248-0578-4. OCLC 903648649.

- Kuykendall, Ralph Simpson (1967). The Hawaiian Kingdom 1874–1893, The Kalakaua Dynasty. Vol. 3. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-87022-433-1. OCLC 500374815. Archived from the original on January 20, 2015. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- Scott, Edward B. (1968). The Saga of the Sandwich Islands. Vol. 1. Crystal Bay, NV: Sierra-Tahoe Publishing Company. OCLC 1667230.

- Vaughan, Palani (2006). "ʻIoane ʻŪkēkē: Hawaiian Dandy, Hawaiian Tragedy". Humu Moʻolelo, Journal of the Hula Arts. 1 (2). Hilo, HI: Humu Moʻolelo: 80–86. OCLC 72467302.

Newspapers and online sources

edit- "Brief Mentions". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. July 31, 1880. p. 3. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- "The Coronation Luau at the Palace". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. February 27, 1883. p. 2. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- "DIED – Hohopa". The Hawaiian Star. Honolulu. May 4, 1903. p. 7. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- "'Hawaiian Dandy' Pau". The Independent. Honolulu. May 4, 1903. p. 3. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- "'Dandy' is Dead". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. May 3, 1903. p. 8. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- "Hawaiian Beau Brummel Dead". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. May 4, 1903. p. 2. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- ""Dandy" In His Prime". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. May 5, 1903. p. 8. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- "'Dandy' is Dead". The Hawaiian Gazette. Honolulu. May 5, 1903. p. 7. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- "'Dandy' Ioane Was A Porter – He Made His Own Fine Raiment – Blossomed In Royalty Days". The Honolulu Advertiser. Honolulu. January 20, 1927. p. 2. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- "Ua Nalohia Kona Leo Uhene". Ka Nupepa Kuokoa (in Hawaiian). Vol. XLI, no. 19. Honolulu. May 8, 1903. p. 6. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- "Make O Ioane Ukeke". Ke Aloha Aina (in Hawaiian). Vol. IX, no. 19. Honolulu. May 9, 1903. p. 6. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- Taylor, Emma Ahuena (February 9, 1935). "Princess Ruth Keelikolani Haughty But Kind, Was A Beloved Alii Of Old Hawaii's Days". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Honolulu. p. 5. Retrieved July 4, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.