Öpir or Öper (Old Norse: Øpiʀ/Œpir, meaning "shouter") was a runemaster who flourished during the late 11th century and early 12th century in Uppland, Sweden.[1] He was the most productive of all the old runemasters[2] and his art is classified as being in the highly refined Urnes style.[3]

Work

editDuring the 11th century, when most runestones were raised, the small number of professional runemasters and their apprentices were contracted to make runestones. When the work was finished, the stone was usually signed with the name of the runemaster.[4]

Öpir had been an associate or an apprentice of the runemaster Visäte.[1][5] He has signed about 50 runestones, and an additional 50 runestones were probably made by him.[1][5] He was active mostly in southern and eastern Uppland, but there are stones made by him also in Gästrikland and Södermanland.[5]

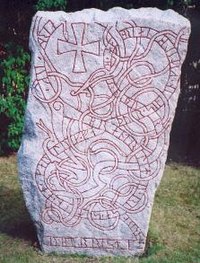

It is a characteristic of his runestones that there is a single rune serpent in the shape of an 8.[6] Moreover, the style is characterized by elegance and control in the complex intervolutions of the rune serpents.[1]

His name Öpir was probably originally a nickname as it means "shouter," and used as his sobriquet.[1][7] On one runestone, U 485 in Marma,[8] he gives his full name: Ofæigʀ Øpiʀ.[1][8]

Language and runes

editThe Old Norse of Öpir was special as the h phoneme does not appear to have been part of his language, and not mastering where to use it, he is known to have added , the Younger Futhark rune for the h phoneme, where it usually did not belong. Some instances of this misspelling are huaru (varu), hustr/huastr (austr or vestr), hut (ut) and Huikiar (the personal name Vigæir).[9] The loss of the initial h phoneme before vowels and its use in the beginning of words where it usually does not appear is a dialect trait still typical of Roslagen (eastern Uppland),[10] where Öpir was active.

However, recent research presents him as a consistent and careful speller with very few language errors,[2] and based on this reinterpretation of his language skills, the different ways he spelled his own name have led to a hypothesis that there were two runemasters named Öpir.[9]

Signed inscriptions

editWith the question regarding whether there was more than one runemaster named Öpir, one scholar accepted the following 46 signed inscriptions as being made by Öpir: Sö 308 in Vid Järnavägen, U 23 in Hilleshögs, U 36 in Svartsjö Djurgård, U 104 in Eds, U 118 in Älvsunda, the now-lost U 122 in Järva Krog, U 142 in Fällbro, the now-lost U 168 in Björkeby, U 179 in Riala, U 181 in Össeby-Garn, U 210 in Åsta, U 229 in Gällsta, the now-lost U 262 in Fresta, U 279 in Skälby, U 287 and U 288 in Vik, U 307 in Ekeby, the now-lost U 315 in Harg, U 462 in Prästgården, U 485 in Marma, U 489 in Morby, U 541 and U 544 in Husby-Lyhundra, the now-lost U 565 in Ekeby Skog, U 566 in Vällingsö, U 687 in Sjusta, U 880 in Skogstibble, U 893 in Högby, U 898 in Norby, U 922 and now-lost U 926 in Uppsala Cathedral, U 961 in Vaksala, U 970 in Bolsta, U 973 in Gränby, the now-lost U 984 in Ekeby, U 993 in Brunnby, U 1034 in Tensta, U 1063 in Källslätt, U 1072 in Bälinge, U 1100 in Sundbro, U 1106 in Äskelunda, U 1159 in Skensta, U 1177 in Hässelby, U Fv1948;168 in Alsike, U Fv1976;107 at Uppsala Cathedral, and the now-lost Gs 4 in Hedesunda.[11] Rundata lists three additional inscriptions: U 896 in Håga and U 940 in Uppsala, both of which have text stating that Öpir "arranged the runes," and U 1022 in Storvreta. It has been suggested that these three inscriptions represent works from the beginning of Öpir's career.[12]

Another inscription that listed by Rundata, Sö 11 in Gryts, is indicated as being signed by a second person named Öpir.

Possible identification with Russian priest

editA record of Упирь (Upir′) appears in a document dated 1047 AD. It is a colophon in a manuscript of the Book of Psalms written by a priest who transcribed the book from Glagolitic into Cyrillic for the Novgorodian Prince Vladimir Yaroslavovich.[13][14] The priest writes that his name is "Upir′ Likhyi " (Упирь Лихый), which would mean something like "Wicked Vampire"[15] or "Foul Vampire."[16] This apparently strange name has been cited as an example of surviving paganism and/or of the use of nicknames as personal names.[17] However, in 1982, Swedish Slavicist Anders Sjöberg suggested that "Upir′ likhyi" was in fact an Old Russian transcription and/or translation of the name of Ofeigr Öpir.[18] Sjöberg argued that Öpir could possibly have lived in Novgorod before moving to Sweden, considering the connection between Eastern Scandinavia and Kievan Rus' at the time. This theory is still controversial, although at least one Swedish historian, Henrik Janson, has expressed support for it.[16]

Gallery

edit-

The cast copy of U 104, one of the Greece Runestones

-

Runestone U 142 is one of the Jarlabanke Runestones and is signed by Öpir.

-

Runestone U 489 is signed by Öpir.

-

Runestone U 933 is attributed to Öpir.

-

The Vaksala Runestone (U 961) is signed by Öpir.

-

Runestone U 1014 is attributed to Öpir.

Notes and references

edit- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f The article Öpir in Nationalencyklopedin (1996).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Runristaren Öpir begåvad konstnär, an announcement on the new dissertation by Marit Åhlén at Uppsala University., retrieved January 14, 2007.

- ^ Fuglesang, Signe Horn (1998). "Swedish Runestones of the Eleventh Century: Ornament and Dating". In Düwel, Klaus; Nowak, Sean (eds.). Runeninschriften als Quellen Interdisziplinärer Forschung. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH. pp. 197–218. ISBN 3-11-015455-2. p. 197.

- ^ Vilka kunde rista runor? at the Swedish National Heritage Board, retrieved March 3, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c The article Runristare at the Swedish Museum of National Antiquities Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved January 13, 2007.

- ^ An article at the site of the Foteviken Museum, retrieved January 13, 2007.

- ^ Thompson, Claiborne W. (1972). "Öpir's Teacher" (PDF). Fornvännen. 67. Swedish National Heritage Board: 6–19. ISSN 1404-9430. Retrieved 2 October 2010. p. 16.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Project Samnordisk Runtextdatabas Svensk - Rundata.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Herschend, Frands (1998). "Ubiʀ, Ybiʀ, ybir: är det U485 Ofeg Öpir?" (PDF). Fornvännen. 93. Swedish National Heritage Board: 97–110. ISSN 1404-9430. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- ^ The article Uppland, subsection dialekter, in Nationalencyklopedin (1996).

- ^ Bertelsen, Lise Gjedssø (2006). "On Öphir's Pictures". In Stoklund, Marie; Nielsen, Michael Lerche; et al. (eds.). Runes and Their Secrets: Studies in Runology. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. pp. 31–64. ISBN 87-635-0428-6. p. 31.

- ^ Källström, Magnus (2010). "Some Thoughts on the Rune-Carver Øpir: A Revaluation of the Storvreta Stone (U 1022) and Some Related Carvings". Futhark. 1. Uppsala University and University of Oslo: 143–160. ISSN 1892-0950. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- ^ Sobolevskij, A. I. "Slavjano-russkaja paleografija" (in Russian). Archived from the original on December 11, 2005.

- ^ http://www.stsl.ru/manuscripts/book.php?col=1&manuscript=089 Archived 2012-11-01 at the Wayback Machine The original manuscript, Книги 16 Пророков толковыя

- ^ "Löfstrand, Elisabeth. V nacale bylo slovo — om språkhistorisk forskning vid Institutionen för slaviska och baltiska språk. Föreläsningar hållna vid Institutionens för slaviska och baltiska språk femtioårsjubileum 1994". Archived from the original on January 1, 2007. Retrieved 2007-02-28.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lind, John H. (2004). "Varangians in Europe's Eastern and Northern Periphery". Ennen & NYT (4). ISSN 1458-1396.

- ^ "Ванькова А.Б., Родионов О.А., Долотова И.А. История России. 6-7 кл : Учебник для основной школы: В 2-х частях. Ч. 1: С древнейших времен до конца XVI века.- М.: ЦГО, 2002.- 256 c. : ил.; 60х90/16 .- ISBN 5-7662-0149-4 (В пер.), 1000 экз. (тир.) УДК 371.671.11:94(47).01/04.. ББК 63.3(2)4я721" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-14. Retrieved 2007-02-28.

- ^ Pop Upir' Lichoj and the Swedish rune-carver Ofeigr Upir. Scando-Slavica, Volume 28, Issue 1 1982, pp. 109-124.