The Ziwiye hoard is a treasure hoard containing gold, silver, and ivory objects, also including a few gold pieces with the shape of a human face, that was uncovered in a plot of land outside Ziwiyeh castle, near the city of Saqqez in Kurdistan Province, Iran, in 1947.

| |

| Coordinates | 36°15′44″N 46°41′16″E / 36.26222°N 46.68778°E |

|---|---|

| Type | Hoard |

Provenance

editObjects from the hoard provide a link between the cultures of the Iranian plateau and the nomadic or Scythian art forms known as the "animal style". "The Scythian motifs adopted by Urartu account for the decoration of the great Treasure of Saqqez brought to light on the south shore of Lake Urmia," was Leonard Woolley's assessment (Woolley 1961 p 176).

Style

editThe hoard contains objects in four styles: "Median", Assyrian, Scythian, proto-Achaemenid, and the provincial native pieces. Dated ca. 700 BC, this collection of objects illustrates the situation of the Iranian plateau as a crossroads of cultural highways—not least of them the Silk Road—which fused disparate cultures to inform early Iranian art. The objects have also been related to finds at Teppe Hasanlu and Marlyk.[1]

Current location

editExamples of the Ziwiye Treasure are scattered among public and private collections. A 'Ziwiye' provenance may have been applied to comparable objects that have passed through the trade since the 1960s. Items attributed to the hoard are currently in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the Louvre in Paris and the British Museum in London.[2][3][4]

Controversy

editThe archaeologist Oscar White Muscarella has questioned the whole account of the finding of the hoard (as he has done with the older Oxus Treasure), pointing out that none of the items were excavated under archaeological conditions, but passed through the hands of dealers. He concludes that "there are no objective sources of information that any of the attributed objects actually were found at Ziwiye, although it is probable that some were", and that the objects have no historical and archaeological value as a group",[5] although many are genuine and "exquisite works of art".[6] In a later work Muscarella denounced several "Ziwiye" objects as modern forgeries.[7]

Gallery

edit-

Gold necklaces

-

Some pieces of Zewiye hoard

-

Gold Rhyton in the form of a Ram's Head

-

Golden plaque

-

golden plaque

-

Jug

-

Ram-shaped pottery object

-

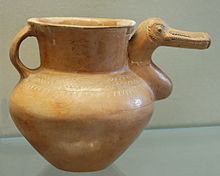

Duck vase

-

Bowl with base

-

Marble bowl

-

Tray

-

Large earthenware jar

-

Bracelet

-

Soldier

-

Golden piece

-

Stone base

-

Shield

-

Necklaces

-

Piece

See also

edit

References

edit- ^ Talbot Rice, 65-74

- ^ Metropolitan Museum Collection

- ^ Louvre Collection

- ^ British Museum Collection

- ^ Muscarella (1977), 955

- ^ Muscarella (1977), 992

- ^ Muscarella (2000), 76-81

Sources

edit- Muscarella, Oscar White (1977), Archaeology, Artifacts and Antiquities of the Ancient Near East: Sites, Cultures, and Proveniences, 2013, BRILL, ISBN 9004236694, 9789004236691, google books, reprinted article from Journal of Field Archaeology, 1977, 4, nr. 2, "Ziwiye and Ziwiye': The Forgery of a Provenience"; google books

- Muscarella, Oscar White (2000), The Lie Became Great. The Forgery of Ancient Near Eastern Cultures. Groningen, Styx 2000, 539 p., ISBN 9056930419, google books

- Talbot Rice, Tamara, Ancient Arts of Central Asia, 1965, Thames & Hudson (Praeger in USA)

- Woolley, Leonard, 1961.The Art of The Middle East, including Persia, Mesopotamia and Palestine. (New York: Crown Publishers)

- Porada, Edith et al., 1962. The Art of Ancient Iran : Pre-Islamic Cultures (New York: Crown) On-line excerpt

- Report of an exploratory dig at Ziwiye by the American archaeologist Robert Dyson in 1963, Penn Museum