XY complete gonadal dysgenesis, also known as Swyer syndrome, is a type of defect hypogonadism in a person whose karyotype is 46,XY. Though they typically have normal vulvas,[1] the person has underdeveloped gonads, fibrous tissue termed "streak gonads", and if left untreated, will not experience puberty. The cause is a lack or inactivation of an SRY gene which is responsible for sexual differentiation. Pregnancy is sometimes possible in Swyer syndrome with assisted reproductive technology.[2][3][4] The phenotype is usually similar to Turner syndrome (45,X0) due to a lack of X inactivation. The typical medical treatment is hormone replacement therapy.[5] The syndrome was named after Gerald Swyer, an endocrinologist based in London.

| XY gonadal dysgenesis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Swyer syndrome |

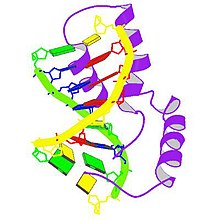

| |

| Protein SRY | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

Signs and symptoms

editThose with Swyer syndrome develop phenotypes typical of females and in most cases, non-reproductive gonads. Individuals are most commonly diagnosed during adolescence after puberty fails to occur.[6]

The consequences of Swyer syndrome without treatment:

- The individual's gonads do not have two X chromosomes, so the breasts will not develop and the uterus will not grow and menstruate until estrogen is administered. This is often given transdermally.

- Their gonads cannot make progesterone, so menstrual periods will not be predictable until progestin is administered, usually as a pill.

- Their gonads cannot produce eggs, so conceiving children is not possible.

- Streak gonads with Y chromosome-containing cells have a high likelihood of developing cancer, especially gonadoblastoma.[7] Streak gonads are usually removed within a year or so of diagnosis, since the cancer can begin during infancy.[citation needed]

- Osteopenia is often present.[8]

Genetics

editGenetic associations of Swyer syndrome include:

| Type | OMIM | Gene | Locus |

|---|---|---|---|

| 46,XY gonadal dysgenesis, complete, SRY-related | 400044 | SRY | Yp11.3 |

| 46,XY gonadal dysgenesis, complete or partial, DHH-related | 233420 | DHH | 12q13.1 |

| 46,XY gonadal dysgenesis, complete or partial, with or without adrenal failure | 612965 | NR5A1 | 9q33 |

| 46,XY gonadal dysgenesis, complete, CBX2-related | 613080 | CBX2 | 17q25 |

| 46,XY gonadal dysgenesis, complete or partial, with 9p24.3 deletion | 154230 | DMRT1/2 | 9p24.3 |

Seven other genes have been identified with probable associations that are as yet less clearly understood.[9]

Pure gonadal dysgenesis

editThere are several forms of gonadal dysgenesis. The term "pure gonadal dysgenesis" (PGD) has been used to describe conditions with normal sets of sex chromosomes (e.g., 46,XX or 46,XY), as opposed to those whose gonadal dysgenesis results from missing all or part of the second sex chromosome. The latter group includes those with Turner syndrome (i.e., 45,X) and its variants, as well as those with mixed gonadal dysgenesis and a mixture of cell lines, some containing a Y chromosome (e.g., 46,XY/45,X).

Thus Swyer syndrome is referred to as PGD, 46,XY, and XX gonadal dysgenesis as PGD, 46,XX.[10] People with PGD have a normal karyotype but may have defects of a specific gene on a chromosome.

Pathogenesis

editThe first known step of sexual differentiation of a male fetus is the development of testes. The early stages of testicular formation in the second month of gestation requires the action of several genes, one of the earliest and most important of which is SRY: the sex-determining region of the Y chromosome.[11][12]

When such a gene is defective, the indifferent gonads fail to differentiate into testes in an XY fetus. Without testes, no testosterone or anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) is produced. Without testosterone, the Wolffian ducts fail to develop, so no internal male organs are formed. Also, the lack of testosterone means that no dihydrotestosterone is formed and consequently the external genitalia fail to virilize, resulting in a normal vulva.[13] Without AMH, the Müllerian ducts develop into normal internal female organs (uterus, fallopian tubes, cervix, vagina).[14]

Diagnosis

editDue to the inability of the streak gonads to produce sex hormones (both estrogens and androgens), most of the secondary sex characteristics do not develop. This is especially true of estrogenic changes such as breast development, widening of the pelvis and hips, and menstrual periods.[15] As the adrenal glands can make limited amounts of androgens and are not affected by this syndrome, most of these persons will develop pubic hair, though it often remains sparse.[16]

Evaluation of delayed puberty usually reveals elevation of gonadotropins, indicating that the pituitary is providing the signal for puberty but the gonads are failing to respond. The next steps of the evaluation usually include checking a karyotype and imaging of the pelvis.[17] The karyotype reveals XY chromosomes and the imaging demonstrates the presence of a uterus but no ovaries (the streak gonads are not usually seen by most imaging). Although an XY karyotype can also indicate a person with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome, the absence of breasts, and the presence of a uterus and pubic hair exclude the possibility. At this point it is usually possible for a physician to make a diagnosis of Swyer syndrome.[18]

Related conditions

editSwyer syndrome represents one phenotypic result of a failure of the gonads to develop properly, and hence is part of a class of conditions termed gonadal dysgenesis. There are many forms of gonadal dysgenesis.[19]

Swyer syndrome is an example of a condition in which an externally unambiguous female body carries dysgenetic, atypical, or abnormal gonads.[20] Other examples include complete androgen insensitivity syndrome, partial X chromosome deletions, lipoid congenital adrenal hyperplasia, and Turner syndrome.[21]

Treatment

editUpon diagnosis, estrogen and progestogen therapy is typically commenced, promoting the development of female characteristics.

Hormone replacement therapy can also reduce the likelihood of osteoporosis.[1]

Epidemiology

editA 2017 study estimated that the incidence of Swyer syndrome is approximately 1 in 100,000 females.[22] Fewer than 100 cases have been reported as of 2018. There are extremely rare instances of familial Swyer syndrome.[23][24]

History

editSwyer syndrome was first described by G. I. M. Swyer in 1955 in a report of two cases.[23]

People with XY gonadal dysgenesis

edit- Arisleyda Dilone, American director and actress[25]

- Sara Forsberg, Finnish singer, songwriter, and television presenter[26]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "Swyer Syndrome". MedlinePlus Genetics.

- ^ Taneja, Jyoti; Ogutu, David; Ah-Moye, Michael (18 October 2016). "Rare successful pregnancy in a patient with Swyer Syndrome". Case Reports in Women's Health. 12: 1–2. doi:10.1016/j.crwh.2016.10.001. ISSN 2214-9112. PMC 5885995. PMID 29629300.

- ^ Urban, Aleksandra; Knap-Wielgus, Weronika; Grymowicz, Monika; Smolarczyk, Roman (September 2021). "Two successful pregnancies after in vitro fertilisation with oocyte donation in a patient with Swyer syndrome – a case report". Przegla̜d Menopauzalny = Menopause Review. 20 (3): 158–161. doi:10.5114/pm.2021.109361. ISSN 1643-8876. PMC 8525253. PMID 34703418.

- ^ Gupta, Anupam; Bajaj, Ritika; Jindal, Umesh N. (2019). "A Rare Case of Swyer Syndrome in Two Sisters with Successful Pregnancy Outcome in Both". Journal of Human Reproductive Sciences. 12 (3): 267–269. doi:10.4103/jhrs.JHRS_14_19. ISSN 0974-1208. PMC 6764226. PMID 31576088.

- ^ Massanyi EZ, Dicarlo HN, Migeon CJ, Gearhart JP (29 December 2012). "Review and management of 46,XY disorders of sex development". J Pediatr Urol. 9 (3): 368–379. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2012.12.002. PMID 23276787.

- ^ "Swyer syndrome". National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD).

- ^ Eh, Zheng; Liu, Weili (June 1994). "A familial 46 XY gonadal dysgenesis and high incidence of embryonic gonadal tumors". Chinese Journal of Cancer Research. 6 (2): 144–148. doi:10.1007/BF02997250. S2CID 84107076. Originally published in Chinese as E, Z; Xu, XL; Li, C; Gao, FZ (May 1981). "家族性XY型性腺发育不全和高发胚胎性肿瘤研究:II.XY型性腺发育不全姐妹中第4人继发无性细胞瘤报告和细胞遗传学检查" [A familial XY gonadal dysgenesis causing high incidence of embryonic gonadal tumors- a report of the fourth dysgerminoma in sibling suffering from 46, XY gonadal dysgenesis]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi (in Chinese). 3 (2): 89–90. PMID 7307902.

- ^ Michala, L.; Goswami, D.; Creighton, SM; Conway, GS (2008). "Swyer syndrome: Presentation and outcomes". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 115 (6): 737–741. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01703.x. PMID 18410658. S2CID 11953597. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ Kremen J, Chan YM, Swartz JM (January 2017). "Recent findings on the genetics of disorders of sex development". Curr Opin Urol. 27 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1097/MOU.0000000000000353. PMC 5877806. PMID 27798415.

- ^ Bomalaski, M. David (February 2005). "A practical approach to intersex". Urologic Nursing. 25 (1): 11–8, 23, quiz 24. PMID 15779688.

- ^ "SRY gene: MedlinePlus Genetics". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "SRY sex determining region Y [Homo sapiens (human)] - Gene - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ Silverman, Ann-Judith. "Gonadal Development" (PDF). Department of Anatomy & Cell Biology. 14 (1) – via Columbia University.

- ^ Wilson, Danielle; Bordoni, Bruno (2022), "Embryology, Mullerian Ducts (Paramesonephric Ducts)", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 32491659, retrieved 20 January 2023

- ^ "Gonadal and Placental Hormones". The Endocrine System. 1 (1). 6 March 2013 – via University of Hawaii.

- ^ Yildiz, Bulent O.; Azziz, Ricardo (2007). "The adrenal and polycystic ovary syndrome". Reviews in Endocrine & Metabolic Disorders. 8 (4): 331–342. doi:10.1007/s11154-007-9054-0. ISSN 1389-9155. PMID 17932770. S2CID 32857950.

- ^ Abitbol, Leah; Zborovski, Stephen; Palmert, Mark R. (19 July 2016). "Evaluation of delayed puberty: what diagnostic tests should be performed in the seemingly otherwise well adolescent?". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 101 (8): 767–771. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2015-310375. ISSN 1468-2044. PMID 27190100. S2CID 25495530.

- ^ "Swyer syndrome". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ King, Thomas F. J.; Conway, Gerard S. (2014). "Swyer syndrome". Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Obesity. 21 (6): 504–510. doi:10.1097/MED.0000000000000113. ISSN 1752-2978. PMID 25314337. S2CID 20181415.

- ^ Zieliñska, Dorota; Zajaczek, Stanislaw; Rzepka-Górska, Izabella (29 May 2007). "Tumors of dysgenetic gonads in Swyer syndrome". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 42 (10): 1721–1724. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.05.029. ISSN 1531-5037. PMID 17923202.

- ^ Gottlieb, Bruce; Trifiro, Mark A. (1993), Adam, Margaret P.; Everman, David B.; Mirzaa, Ghayda M.; Pagon, Roberta A. (eds.), "Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome", GeneReviews®, Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle, PMID 20301602, retrieved 20 January 2023

- ^ Witchel, Selma Feldman (April 2018). "Disorders of Sex Development". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 48: 90–102. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2017.11.005. ISSN 1521-6934. PMC 5866176. PMID 29503125.

- ^ a b Banoth M, Naru RR, Inamdar MB, Chowhan AK (May 2018). "Familial Swyer syndrome: a rare genetic entity". Gynecol. Endocrinol. 34 (5): 389–393. doi:10.1080/09513590.2017.1393662. PMID 29069951. S2CID 4452231.

- ^ "Swyer syndrome". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Mami Y Yo y Mi Gallito, by Director Arisleyda Dilone – Intersex Campaign for Equality". www.intersexequality.com. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Kantola, Iida (27 October 2023). "Sara Forsberg kertoo olevansa intersukupuolinen". Ilta-Sanomat (in Finnish).

Further reading

edit- Stoicanescu D, Belengeanu V, et al. (2006). "Complete gonadal dysgenesis with XY chromosomal constitution". Acta Endocrinologica. 2 (4): 465–70. doi:10.4183/aeb.2006.465.

External links

edit