William Seward Burroughs II (/ˈbʌroʊz/; February 5, 1914 – August 2, 1997) was an American writer and visual artist. He is widely considered a primary figure of the Beat Generation and a major postmodern author who influenced popular culture and literature.[2][3][4] Burroughs wrote 18 novels and novellas, six collections of short stories, and four collections of essays. Five books of his interviews and correspondences have also been published. He was initially briefly known by the pen name William Lee. He also collaborated on projects and recordings with numerous performers and musicians, made many appearances in films, and created and exhibited thousands of visual artworks, including his celebrated "shotgun art".[5]

William S. Burroughs | |

|---|---|

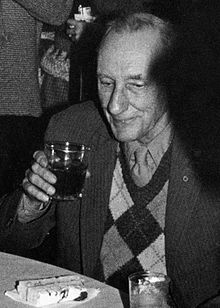

Burroughs in 1983 | |

| Born | William Seward Burroughs II February 5, 1914 St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | August 2, 1997 (aged 83) Lawrence, Kansas, U.S. |

| Pen name | William Lee |

| Occupation | Author |

| Education | Harvard University (BA) |

| Genre | Beat literature, surrealism, satire |

| Literary movement | Beat Generation, postmodernism, science fiction |

| Notable works | Junkie (1953) Naked Lunch (1959) The Nova Trilogy (1961–1964) Cities of the Red Night (1981) The Place of Dead Roads (1983) |

| Spouse | Ilse Klapper (1937–1946)[1] Joan Vollmer (1946–1951) |

| Children | William S. Burroughs Jr. |

| Relatives | William Seward Burroughs I (grandfather) Ivy Lee (maternal uncle) |

| Signature | |

Burroughs was born into a wealthy family in St. Louis, Missouri. He was a grandson of inventor William Seward Burroughs I, who founded the Burroughs Corporation, and a nephew of public relations manager Ivy Lee.

Burroughs attended Harvard University, where he studied English, then anthropology as a postgraduate, and went on to medical school in Vienna. In 1942, he enlisted in the U.S. Army to serve during World War II. After being turned down by both the Office of Strategic Services and the Navy, he veered into substance abuse, beginning with morphine and developing a heroin addiction that would affect him for the rest of his life.

In 1943, while living in New York City, he befriended Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac. This liaison would become the foundation of the Beat Generation, later a defining influence on the 1960s counterculture.

Burroughs found success with his confessional first novel, Junkie (1953), but is perhaps best known for his third novel, Naked Lunch (1959). It became the subject of one of the last major literary censorship cases in the United States after its US publisher, Grove Press, was sued for violating a Massachusetts obscenity statute.

Burroughs is believed to have killed his second wife, Joan Vollmer, in 1951 in Mexico City. He initially claimed that he had accidentally shot her while drunkenly attempting a "William Tell" stunt.[6] He later told investigators that he had been showing his pistol to friends when it fell and hit the table, firing the bullet that killed Vollmer.[7] After he fled Mexico back to the United States, he was convicted of manslaughter in absentia and received a two-year suspended sentence.

Much of Burroughs' work is highly experimental and features unreliable narrators, but it is also semi-autobiographical, often drawing from his experiences as a heroin addict. He lived at various times in Mexico City, London, Paris, and the Tangier International Zone in Morocco, and traveled in the Amazon rainforest — and featured these places in many of his novels and stories. With Brion Gysin, Burroughs popularized the cut-up, an aleatory literary technique, featuring heavily in such works of his as The Nova Trilogy (1961–1964). His writing also engages frequent mystical, occult, or otherwise magical themes, constant preoccupations in both his fiction and real life.[4][8]

In 1983, Burroughs was elected to the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters. In 1984, he was awarded the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by France.[9] Jack Kerouac called Burroughs the "greatest satirical writer since Jonathan Swift";[10] he owed this reputation to his "lifelong subversion"[11] of the moral, political, and economic systems of modern American society, articulated in often darkly humorous sardonicism. J. G. Ballard considered Burroughs to be "the most important writer to emerge since the Second World War," while Norman Mailer declared him "the only American writer who may be conceivably possessed by genius."[10]

Early life and education

editBurroughs was born in 1914, the younger of two sons born to Mortimer Perry Burroughs (June 16, 1885 – January 5, 1965) and Laura Hammon Lee (August 5, 1888 – October 20, 1970). Of prominent English ancestry, his family lived in St. Louis, Missouri. His grandfather, William Seward Burroughs I, had founded the Burroughs Adding Machine company, which evolved into the Burroughs Corporation. His mother was Laura Hammond Lee Burroughs, whose brother, Ivy Lee, was an advertising pioneer later employed as a publicist for the Rockefellers. His father ran an antiques and gift shop, Cobblestone Gardens, in St. Louis and later in Palm Beach, Florida, when they relocated. Burroughs would later write of growing up in a "family where displays of affection were considered embarrassing".[8]: 26

During his childhood, Burroughs developed a lifelong interest in magic and the occult, which would eventually find their way repeatedly into his writings.[a] Significantly, he later described how, as a child, he'd seen an apparition of a green reindeer in the woods, which he identified as a totem animal,[b] as well as a vision of ghostly gray figures at play in his bedroom.[c]

As a boy, Burroughs lived on Pershing Avenue (now Pershing Place) in St. Louis's Central West End. He attended John Burroughs School in St. Louis, where his first published essay — "Personal Magnetism", which revolved around telepathic mind-control — was printed in the John Burroughs Review in 1929.[15] He then attended the Los Alamos Ranch School in New Mexico, which was stressful for him. The school was a boarding school for the wealthy, "where the spindly sons of the rich could be transformed into manly specimens".[8]: 44 Burroughs kept journals documenting an erotic attachment to another boy. According to his own account, he destroyed these later, ashamed of their content.[16] He kept his sexual orientation concealed from his family well into adulthood. A common story says[17] that he was expelled from Los Alamos after taking chloral hydrate in Santa Fe with a fellow student. Yet, according to his own account, he left voluntarily: "During the Easter vacation of my second year I persuaded my family to let me stay in St. Louis."[16]

Harvard University

editBurroughs finished high school at Taylor School in Clayton, Missouri, and in 1932 left home to pursue an arts degree at Harvard University, where he was affiliated with Adams House. During the summers, he worked as a cub reporter for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, covering the police docket. He disliked the work, and refused to cover some events, like the death of a drowned child. He lost his virginity in an East St. Louis, Illinois, brothel that summer with a female prostitute whom he regularly patronized.[8]: papers, p.62 While at Harvard, Burroughs made trips to New York City and was introduced to the gay subculture there. He visited lesbian dives, piano bars, and the Harlem and Greenwich Village homosexual underground with Richard Stern, a wealthy friend from Kansas City. They would drive from Boston to New York in a reckless fashion. Once, Stern scared Burroughs so badly that he asked to be let out of the vehicle.[8]: 611

Burroughs graduated from Harvard in 1936. According to Ted Morgan's Literary Outlaw,[8]

His parents, upon his graduation, had decided to give him a monthly allowance of $200 out of their earnings from Cobblestone Gardens, a substantial sum in those days. It was enough to keep him going, and indeed it guaranteed his survival for the next twenty-five years, arriving with welcome regularity. The allowance was a ticket to freedom; it allowed him to live where he wanted to and to forgo employment.[8]: 69–70

Burroughs's parents sold the rights to his grandfather's invention and had no share in the Burroughs Corporation. Shortly before the 1929 stock market crash, they sold their stock for $200,000 (equivalent to approximately $3,500,000 in today's funds[18]).[19]

Europe and First Marriage

editAfter Burroughs graduated from Harvard, his formal education ended, except for brief flirtations with graduate study of anthropology at Columbia and medicine in Vienna, Austria. He traveled to Europe and became involved in Austrian and Hungarian Weimar-era gay culture; he picked up young men in steam baths in Vienna and moved in a circle of exiles, homosexuals, and runaways. There, he met Ilse Klapper, born Herzfeld (1900–1982), a German Jewish woman fleeing her country's Nazi government.[1] The two were never romantically involved, but Burroughs married her, in Croatia, against the wishes of his parents, to allow her to gain a visa to the United States. She made her way to New York City, and eventually divorced Burroughs, although they remained friends for many years.[8]: 65–68

After returning to the United States, he held a string of uninteresting jobs. In 1939, his mental health became a concern for his parents, especially after he deliberately severed the last joint of his left little finger at the knuckle to impress a man with whom he was infatuated.[20] This event made its way into his early fiction as the novella "The Finger".

Beginning of the Beats

editBurroughs enlisted in the U.S. Army early in 1942, shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor brought the United States into World War II. But when he was classified as a 1-A infantry, not an officer, he became dejected. His mother recognized her son's depression and got Burroughs a civilian disability discharge – a release from duty based on the premise that he should have not been allowed to enlist due to previous mental instability. After being evaluated by a family friend, who was also a neurologist at a psychiatric treatment center, Burroughs waited five months in limbo at Jefferson Barracks outside St. Louis before being discharged. During that time he met a Chicago soldier also awaiting release, and once Burroughs was free, he moved to Chicago and held a variety of jobs, including one as an exterminator. When two of his friends from St. Louis – University of Chicago student Lucien Carr and his admirer, David Kammerer – left for New York City, Burroughs followed.

Addiction and Joan Vollmer

editIn 1945, Burroughs began living with Joan Vollmer Adams in an apartment they shared with Jack Kerouac and Edie Parker, Kerouac's first wife.[21] Vollmer Adams was married to a G.I. with whom she had a young daughter, Julie Adams.

Burroughs and Kerouac got into trouble with the law for failing to report a murder involving Lucien Carr, who had killed David Kammerer in a confrontation over Kammerer's incessant and unwanted advances. This incident inspired Burroughs and Kerouac to collaborate on a novel titled And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks, completed in 1945. The two fledgling authors were unable to get it published during their lifetimes, but the manuscript was eventually published in November 2008 by Grove Press and Penguin Books.

During this time, Burroughs began using morphine and became addicted. He eventually sold heroin in Greenwich Village to support his habit. Vollmer also became an addict, but her drug of choice was Benzedrine, an amphetamine sold over the counter at that time. Because of her addiction and social circle, her husband immediately divorced her after returning from the war. With urging from Allen Ginsberg, and also perhaps Kerouac, Burroughs became intellectually and emotionally linked with Vollmer and by summer 1945, had moved in with Vollmer and her daughter. In spring 1946, Burroughs was arrested for forging a narcotics prescription. Vollmer asked her psychiatrist, Lewis Wolberg, to sign a surety bond for Burroughs's release. As part of his release, Burroughs returned to St. Louis under his parents' care, after which he left for Mexico to get a divorce from Ilse Klapper. Meanwhile, Vollmer's addiction led to a temporary psychosis that resulted in her admission to Bellevue Hospital, which endangered the custody of her child. Upon hearing this, Burroughs immediately returned to New York City to gain her release, asking her to marry him. Their marriage was never formalized, but she lived as his common-law wife.

They returned to St. Louis to visit Burroughs's parents and then moved with her daughter to Texas.[22] Vollmer soon became pregnant with Burroughs's child. Their son, William S. Burroughs Jr., was born in 1947. The family moved briefly to New Orleans in 1948.[23]

Mexico and South America (1950–1952)

editIn New Orleans, police stopped Burroughs's car one evening. They found an unregistered handgun belonging to him as well as a letter from Ginsberg that contained details about the sale of marijuana. The police then searched Burroughs’s home, where they discovered his stash of drugs and half a dozen or more firearms.[24] Burroughs fled to Mexico to escape possible detention in Louisiana's Angola State Prison. Vollmer and their children followed him. Burroughs planned to stay in Mexico for at least five years, the length of his charge's statute of limitations. Burroughs also attended classes at the Mexico City College in 1950, studying Spanish, as well as Mesoamerican manuscripts (codices) and the Mayan language with R. H. Barlow.

Killing of Vollmer

editTheir life in Mexico was by all accounts an unhappy one.[25] Without heroin and suffering from Benzedrine abuse, Burroughs began to pursue other men as his libido returned, while Vollmer, feeling abandoned, started to drink heavily and mock Burroughs openly.[22]

One night, while drinking with friends at a party above the Bounty Bar in Mexico City,[26] a drunk Burroughs allegedly took his handgun from his travel bag and told his wife, "It's time for our William Tell act." There is no indication that they had performed such an action previously.[25] Vollmer, who was also drinking heavily and undergoing amphetamine withdrawal, allegedly obliged him by putting a highball glass on her head. Burroughs shot Vollmer in the head, killing her almost immediately.[27]

Soon after the incident, Burroughs changed his account, claiming that he had dropped his gun and it had accidentally fired.[28] Burroughs spent 13 days in jail before his brother came to Mexico City and bribed Mexican lawyers and officials to release Burroughs on bail while he awaited trial for the killing, which was ruled culpable homicide.

Vollmer's daughter, Julie Adams, went to live with her grandmother, and William S. Burroughs Jr. went to St. Louis to live with his grandparents. Burroughs reported every Monday morning to the jail in Mexico City while his prominent Mexican attorney worked to resolve the case. According to James Grauerholz, two witnesses had agreed to testify that the gun had fired accidentally while he was checking to see if it was loaded, with ballistics experts bribed to support this story.[8]: 202 Nevertheless, the trial was continuously delayed and Burroughs began to write what would eventually become the short novel Queer while awaiting his trial. Upon Burroughs's attorney fleeing Mexico in light of his own legal problems, Burroughs decided, according to Ted Morgan, to "skip" and return to the United States. He was convicted in absentia of homicide and was given a two-year suspended sentence.[8]: 214

Although Burroughs was writing before his murder of Joan Vollmer, this event marked him and, biographers argue, his work for the rest of his life.[8]: 197–198 Vollmer's death also resonated with Allen Ginsberg, who wrote of her in Dream Record: June 8, 1955, "Joan, what kind of knowledge have the dead? Can you still love your mortal acquaintances? What do you remember of us?" In Burroughs: The Movie, Ginsberg claimed that Vollmer had seemed possibly suicidal in the weeks leading up to her death, and he suggested that this may have been a factor in her willingness to take part in the risky William Tell stunt.[29]

The Yage Letters

editAfter leaving Mexico, Burroughs drifted through South America for several months, seeking out a drug called yagé, which promised to give the user telepathic abilities. A book composed of letters between Burroughs and Ginsberg, The Yage Letters, was published in 1963 by City Lights Books. In 2006, a re-edited version, The Yage Letters Redux, showed that the letters were largely fictionalised from Burroughs's notes.

Beginning of literary career

editBurroughs described Vollmer's death as a pivotal event in his life, and one that provoked his writing by exposing him to the risk of possession by a malevolent entity he called "the Ugly Spirit":

I am forced to the appalling conclusion that I would never have become a writer but for Joan's death, and to a realization of the extent to which this event has motivated and formulated my writing. I live with the constant threat of possession, and a constant need to escape from possession, from Control. So the death of Joan brought me in contact with the invader, the Ugly Spirit, and maneuvered me into a life long struggle, in which I have had no choice except to write my way out.[30]

As Burroughs makes clear, he meant this reference to "possession" to be taken absolutely literally, stating: "My concept of possession is closer to the medieval model than to modern psychological explanations ... I mean a definite possessing entity."[30] Burroughs' writing was intended as a form of "sorcery", in his own words[31] – to disrupt language via methods such as the cut-up technique, and thus protect himself from possession.[d][e][f][g] Later in life, Burroughs described the Ugly Spirit as "Monopolistic, acquisitive evil. Ugly evil. The ugly American", and took part in a shamanic ceremony with the explicit aim of exorcising the Ugly Spirit.[36]

Oliver Harris has questioned Burroughs's claim that Vollmer's death catalysed his writing, highlighting the importance for Queer of Burroughs's traumatic relationship with the boyfriend fictionalized in the story as Eugene Allerton, rather than Burroughs's shooting of Vollmer. In any case, he had begun to write in 1945. Burroughs and Kerouac collaborated on And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks, a mystery novel loosely based on the Carr–Kammerer situation and that at the time remained unpublished. Years later, in the documentary What Happened to Kerouac?, Burroughs described it as "not a very distinguished work". An excerpt of this work, in which Burroughs and Kerouac wrote alternating chapters, was finally published in Word Virus,[37] a compendium of William Burroughs's writing that was published by his biographer after his death in 1997. The complete novel was finally published by Grove Press in 2008.

Before killing Vollmer, Burroughs had largely completed his first novel, Junkie, which he wrote at the urging of Allen Ginsberg, who was instrumental in getting the work published as a cheap mass-market paperback.[38] Ace Books published the novel in 1953 as part of an Ace Double under the pen name William Lee, retitling it Junkie: Confessions of an Unredeemed Drug Addict (it was later republished as Junkie, then in 1977 as Junky, and finally in 2003 as Junky: the definitive text of 'Junk', edited by Oliver Harris).[38]

Tangier

editDuring 1953, Burroughs was at loose ends. Due to legal problems, he was unable to live in the cities toward which he was most inclined. He spent time with his parents in Palm Beach, Florida, and in New York City with Allen Ginsberg. When Ginsberg refused his romantic advances,[39] Burroughs went to Rome to meet Alan Ansen on a vacation financed from his parents' continuing support. He found Rome and Ansen's company dreary and, inspired by Paul Bowles' fiction, he decided to head for the Tangier International Zone,[8]: 232–234 where he rented a room and began to write a large body of text that he personally referred to as Interzone.[40]

To Burroughs, all signs directed a return to Tangier, a city where drugs were freely available and where financial support from his family would continue. He realized that in the Moroccan culture he had found an environment that synchronized with his temperament and afforded no hindrances to pursuing his interests and indulging in his chosen activities. He left for Tangier in November 1954 and spent the next four years there working on the fiction that would later become Naked Lunch, as well as attempting to write commercial articles about Tangier. He sent these writings to Ginsberg, his literary agent for Junkie, but none were published until 1989 when Interzone, a collection of short stories, was published. Under the strong influence of a marijuana confection known as majoun and a German-made opioid called Eukodol, Burroughs settled in to write. Eventually, Ginsberg and Kerouac, who had traveled to Tangier in 1957, helped Burroughs type, edit, and arrange these episodes into Naked Lunch.[8]: 238–242

Naked Lunch

editWhereas Junkie and Queer were conventional in style, Naked Lunch was his first venture into a nonlinear style. After the publication of Naked Lunch, a book whose creation was to a certain extent the result of a series of contingencies, Burroughs was exposed to Brion Gysin's cut-up technique at the Beat Hotel in Paris in October 1959. He began slicing up phrases and words to create new sentences.[41] At the Beat Hotel, Burroughs discovered "a port of entry" into Gysin's canvases: "I don't think I had ever seen painting until I saw the painting of Brion Gysin."[42] The two would cultivate a long-term friendship that revolved around a mutual interest in artworks and cut-up techniques. Scenes were slid together with little care for narrative.

Excerpts from Naked Lunch were first published in the United States in 1958. The novel was initially rejected by City Lights Books, the publisher of Ginsberg's Howl; and Olympia Press publisher Maurice Girodias, who had published English-language novels in France that were controversial for their subjective views of sex and antisocial characters. Nevertheless, Ginsberg managed to get excerpts published in Black Mountain Review and Chicago Review in 1958. Irving Rosenthal, student editor of Chicago Review, a quarterly journal partially subsidized by the university, promised to publish more excerpts from Naked Lunch, but he was fired from his position in 1958 after Chicago Daily News columnist Jack Mabley called the first excerpt obscene. Rosenthal went on to publish more in his newly created literary journal Big Table No. 1; however, the United States Postmaster General ruled that copies could not be mailed to subscribers on the basis of obscenity laws. John Ciardi did get a copy and wrote a positive review of the work, prompting a telegram from Allen Ginsberg praising the review.[43] This controversy made Naked Lunch interesting to Girodias again, and he published the novel in 1959.[44]

After the novel was published, it became notorious across Europe and the United States, garnering interest from not just members of the counterculture of the 1960s, but also literary critics such as Mary McCarthy. Once published in the United States, Naked Lunch was prosecuted as obscene by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, followed by other states. In 1966, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court declared the work "not obscene" on the basis of criteria developed largely to defend the book. The case against Burroughs's novel still stands as the last obscenity trial against a work of literature – that is, a work consisting of words only, and not including illustrations or photographs – prosecuted in the United States.

The Word Hoard, the collection of manuscripts that produced Naked Lunch, also produced parts of the later works The Soft Machine (1961), The Ticket That Exploded (1962), and Nova Express (1964). These novels feature extensive use of the cut-up technique that influenced all of Burroughs's subsequent fiction to a degree. During Burroughs's friendship and artistic collaborations with Gysin and Ian Sommerville, the technique was combined with images, Gysin's paintings, and sound, via Sommerville’s tape recorders. Burroughs was so dedicated to the cut-up method that he often defended his use of the technique before editors and publishers, most notably Dick Seaver at Grove Press in the 1960s[8]: 425 and Holt, Rinehart & Winston in the 1980s. The cut-up method, because of its random or mechanical basis for text generation, combined with the possibilities of mixing in text written by other writers, deemphasizes the traditional role of the writer as creator or originator of a string of words, while simultaneously exalting the importance of the writer's sensibility as an editor.[citation needed] In this sense, the cut-up method may be considered as analogous to the collage method in the visual arts.[citation needed] New restored editions of The Nova Trilogy (or Cut-Up Trilogy), edited by Oliver Harris (President of the European Beat Studies Network) and published in 2014, included notes and materials to reveal the care with which Burroughs used his methods and the complex histories of his manuscripts.

Paris and the "Beat Hotel"

editBurroughs moved into a rundown hotel in the Latin Quarter of Paris in 1959 when Naked Lunch was still looking for a publisher. Tangier, with its political unrest, and criminals with whom he had become involved, became dangerous to Burroughs.[45] He went to Paris to meet Ginsberg and talk with Olympia Press. He left behind a criminal charge which eventually caught up with him in Paris. Paul Lund, a British former career criminal and cigarette smuggler whom Burroughs met in Tangier, was arrested on suspicion of importing narcotics into France. Lund gave up Burroughs, and evidence implicated Burroughs in the importation of narcotics into France. When the Moroccan authorities forwarded their investigation to French officials, Burroughs faced criminal charges in Paris for conspiracy to import opiates. It was during this impending case that Maurice Girodias published Naked Lunch; its appearance helped to get Burroughs a suspended sentence, since a literary career, according to Ted Morgan, is a respected profession in France.

The "Beat Hotel" was a typical European-style boarding house hotel, with common toilets on every floor, and a small place for personal cooking in the room. Life there was documented by the photographer Harold Chapman, who lived in the attic room. This shabby, inexpensive hotel was populated by Gregory Corso, Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky for several months after Naked Lunch first appeared.

Burroughs's time at the Beat Hotel was dominated by occult experiments – "mirror-gazing, scrying, trance and telepathy, all fuelled by a wide variety of mind-altering drugs".[46] Later, Burroughs would describe "visions" obtained by staring into the mirror for hours at a time – his hands transformed into tentacles,[h] or his whole image transforming into some strange entity,[i] or visions of far-off places,[48] or of other people rapidly undergoing metamorphosis.[j] It was from this febrile atmosphere that the famous cut-up technique emerged.

The actual process by which Naked Lunch was published was partly a function of its "cut-up" presentation to the printer. Girodias had given Burroughs only ten days to prepare the manuscript for print galleys, and Burroughs sent over the manuscript in pieces, preparing the parts in no particular order. When it was published in this authentically random manner, Burroughs liked it better than the initial plan. International rights to the work were sold soon after, and Burroughs used the $3,000 advance from Grove Press to buy drugs (equivalent to approximately $31,000 in today's funds[18]).[8]: 316–326 Naked Lunch was featured in a 1959 Life magazine cover story, partly as an article that highlighted the growing Beat literary movement. During this time Burroughs found an outlet for material otherwise rendered unpublishable in Jeff Nuttall's My Own Mag.[49] Also, poetry by Burroughs appeared in the avant garde little magazine Nomad at the beginning of the 1960s.

The London years

editBurroughs left Paris for London in 1960 to visit Dr. Dent, a well-known English medical doctor who spearheaded a reputedly painless heroin withdrawal treatment using the drug apomorphine.[50] Dent's apomorphine cure was also used to treat alcoholism, although it was held by several people who undertook it to be no more than straightforward aversion therapy. Burroughs, however, was convinced. Following his first cure, he wrote a detailed appreciation of apomorphine and other cures, which he submitted to The British Journal of Addiction (Vol. 53, 1956) under the title "Letter From A Master Addict To Dangerous Drugs"; this letter is appended to many editions of Naked Lunch.

Though he ultimately relapsed, Burroughs ended up working out of London for six years, traveling back to the United States on several occasions, including one time escorting his son to the Lexington Narcotics Farm and Prison after the younger Burroughs had been convicted of prescription fraud in Florida. In the "Afterword" to the compilation of his son's two previously published novels Speed and Kentucky Ham, Burroughs writes that he thought he had a "small habit" and left London quickly without any narcotics because he suspected the U.S. customs would search him very thoroughly on arrival. He claims he went through the most excruciating two months of opiate withdrawal while seeing his son through his trial and sentencing, traveling with Billy to Lexington, Kentucky from Miami to ensure that his son entered the hospital that he had once spent time in as a volunteer admission.[51] Earlier, Burroughs revisited St. Louis, Missouri, taking a large advance from Playboy to write an article about his trip back to St. Louis, one that was eventually published in The Paris Review, after Burroughs refused to alter the style for Playboy’s publishers. In 1968 Burroughs joined Jean Genet, John Sack, and Terry Southern in covering the 1968 Democratic National Convention for Esquire magazine. Southern and Burroughs, who had first become acquainted in London, would remain lifelong friends and collaborators. In 1972, Burroughs and Southern unsuccessfully attempted to adapt Naked Lunch for the screen in conjunction with American game-show producer Chuck Barris.[52]

Burroughs supported himself and his addiction by publishing pieces in small literary presses. His avant-garde reputation grew internationally as hippies and college students discovered his earlier works. He developed a close friendship with Antony Balch and lived with a young hustler named John Brady who continuously brought home young women despite Burroughs's protestations. In the midst of this personal turmoil, Burroughs managed to complete two works: a novel written in screenplay format, The Last Words of Dutch Schultz (1969); and the traditional prose-format novel The Wild Boys (1971).

It was during his time in London that Burroughs began using his "playback" technique in an attempt to place curses on various people and places who had drawn his ire, including the Moka coffee bar[53][k] and the London HQ of Scientology.[l] Burroughs himself related the Moka coffee bar incident:

Here is a sample operation carried out against the Moka Bar at 29 Frith Street, London, W1, beginning on August 3, 1972. Reverse Thursday. Reason for operation was outrageous and unprovoked discourtesy and poisonous cheesecake. Now to close in on the Moka Bar. Record. Take pictures. Stand around outside. Let them see me. They are seething around in there ... Playback would come later with more pictures ... Playback was carried out a number of times with more pictures. Their business fell off. They kept shorter and shorter hours. October 30, 1972, the Moka Bar closed. The location was taken over by the Queen's Snack Bar.[56]

In the 1960s, Burroughs joined and then left the Church of Scientology. In talking about the experience, he claimed that the techniques and philosophy of Scientology helped him and that he felt that further study of Scientology would produce great results.[57] He was skeptical of the organization itself, and felt that it fostered an environment that did not accept critical discussion.[58] His subsequent critical writings about the church and his review of Inside Scientology by Robert Kaufman led to a battle of letters between Burroughs and Scientology supporters in the pages of Rolling Stone magazine.

Return to United States

editIn 1974, concerned about his friend's well-being, Allen Ginsberg gained for Burroughs a contract to teach creative writing at the City College of New York. Burroughs successfully withdrew from heroin use and moved to New York. He eventually found an apartment, affectionately dubbed "The Bunker", on the Lower East Side of Manhattan at 222 Bowery.[59] The dwelling was a partially converted YMCA gym, complete with lockers and communal showers. The building fell within New York City rent control policies that made it extremely cheap; it was only about four hundred dollars a month until 1981 when the rent control rules changed, doubling the rent overnight.[60] Burroughs added "teacher" to the list of jobs he did not like, as he lasted only a semester as a professor; he found the students uninteresting and without much creative talent. Although he needed income desperately, he turned down a teaching position at the University at Buffalo for $15,000 a semester. "The teaching gig was a lesson in never again. You were giving out all this energy and nothing was coming back."[8]: 477 His savior was the newly arrived twenty-one-year-old bookseller and Beat Generation devotee James Grauerholz, who worked for Burroughs part-time as a secretary as well as in a bookstore. Grauerholz suggested the idea of reading tours. Grauerholz had managed several rock bands in Kansas and took the lead in booking for Burroughs reading tours that would help support him throughout the next two decades. It raised his public profile, eventually aiding in his obtaining new publishing contracts. Through Grauerholz, Burroughs became a monthly columnist for the noted popular culture magazine Crawdaddy, for which he interviewed Led Zeppelin's Jimmy Page in 1975. Burroughs decided to relocate back to the United States permanently in 1976. He then began to associate with New York cultural players such as Andy Warhol, John Giorno, Lou Reed, Patti Smith, and Susan Sontag, frequently entertaining them at the Bunker; he also visited venues like CBGB to watch the likes of Patti Smith perform.[61] Throughout early 1977, Burroughs collaborated with Southern and Dennis Hopper on a screen adaptation of Junky. It was reported in The New York Times that Burroughs himself would appear in the film. Financed by a reclusive acquaintance of Burroughs, the project lost traction after financial problems and creative disagreements between Hopper and Burroughs.[62][63]

In 1976, he appeared in Rosa von Praunheim's New York documentary Underground & Emigrants.

Organized by Columbia professor Sylvère Lotringer, Giorno, and Grauerholz, the Nova Convention was a multimedia retrospective of Burroughs's work held from November 30 to December 2, 1978, at various locations throughout New York. The event included readings from Southern, Ginsberg, Smith, and Frank Zappa (who filled in at the last minute for Keith Richards, then entangled in a legal problem), in addition to panel discussions with Timothy Leary and Robert Anton Wilson and concerts featuring The B-52's, Suicide, Philip Glass, and Debbie Harry and Chris Stein.

In 1976, Burroughs was having dinner with his son, William S. "Billy" Burroughs Jr., and Allen Ginsberg in Boulder, Colorado, at Ginsberg's Buddhist poetry school (Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics) at Chogyam Trungpa's Naropa University when Billy began to vomit blood. Burroughs Sr. had not seen his son for over a year and was alarmed at his appearance when Billy arrived at Ginsberg's apartment. Although Billy had successfully published two short novels in the 1970s and was deemed by literary critics like Ann Charters as a bona fide "second generation beat writer",[64] his brief marriage to a teenage waitress had disintegrated. Billy was a constant drinker, and there were long periods when he was out of contact with any of his family or friends. The diagnosis was liver cirrhosis so complete that the only treatment was a rarely performed liver transplant operation. Fortunately, the University of Colorado Medical Center was one of two places in the nation that performed transplants under the pioneering work of Dr. Thomas Starzl. Billy underwent the procedure and beat the thirty-percent survival odds. His father spent time in 1976 and 1977 in Colorado, helping Billy through additional surgeries and complications. Ted Morgan's biography asserts that their relationship was not spontaneous and lacked real warmth or intimacy. Allen Ginsberg was supportive to both Burroughs and his son throughout the long period of recovery.[8]: 495–536

In London, Burroughs had begun to write what would become the first novel of a trilogy, published as Cities of the Red Night (1981), The Place of Dead Roads (1983), and The Western Lands (1987). Grauerholz helped edit Cities when it was first rejected by Burroughs's long-time editor Dick Seaver at Holt Rinehart, after it was deemed too disjointed. The novel was written as a straight narrative and then chopped up into a more random pattern, leaving the reader to sort through the characters and events. This technique differed from the author's earlier cut-up methods, which were accidental from the start. Nevertheless, the novel was reassembled and published, still without a straight linear form, but with fewer breaks in the story. The trilogy featured time-travel adventures in which Burroughs's narrators rewrote episodes from history to reform mankind.[8]: 565 Reviews were mixed for Cities. Novelist and critic Anthony Burgess panned the work in Saturday Review, saying Burroughs was boring readers with repetitive episodes of pederast fantasy and sexual strangulation that lacked any comprehensible world view or theology; other reviewers, like J. G. Ballard, argued that Burroughs was shaping a new literary "mythography".[8]: 565

In 1981, Billy Burroughs died in Florida. He had cut off contact with his father several years before, even publishing an article in Esquire magazine claiming his father had poisoned his life and claiming that he had been molested as a fourteen-year-old by one of his father's friends while visiting Tangier. The liver transplant had not cured his urge to drink, and Billy suffered from serious health complications years after the operation. After he had stopped taking his transplant rejection drugs, he was found near the side of a Florida highway by a stranger. He died shortly afterward. Burroughs was in New York when he heard from Allen Ginsberg of Billy's death.

Burroughs, by 1979, was once again addicted to heroin. The cheap heroin that was easily purchased outside his door on the Lower East Side "made its way" into his veins, coupled with "gifts" from the overzealous if well-intentioned admirers who frequently visited the Bunker. Although Burroughs would have episodes of being free from heroin, from this point until his death he was regularly addicted to the drug. In an introduction to Last Words: The Final Journals of William S. Burroughs, James Grauerholz (who managed Burroughs's reading tours in the 1980s and 1990s) mentions that part of his job was to deal with the "underworld" in each city to secure the author's drugs.[65]

Later years in Kansas

editBurroughs moved to Lawrence, Kansas, in 1981, taking up residence at 1927 Learnard Avenue where he would spend the rest of his life. He once told a Wichita Eagle reporter that he was content to live in Kansas, saying, "The thing I like about Kansas is that it's not nearly as violent, and it's a helluva lot cheaper. And I can get out in the country and fish and shoot and whatnot."[66] In 1984, he signed a seven-book deal with Viking Press after he signed with literary agent Andrew Wylie. This deal included the publication rights to the unpublished 1952 novel Queer. With this money he purchased a small bungalow for $29,000.[8]: 596 He was finally inducted into the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters in 1983 after several attempts by Allen Ginsberg to get him accepted. He attended the induction ceremony in May 1983. Lawrence Ferlinghetti remarked the induction of Burroughs into the Academy proved Herbert Marcuse's point that capitalistic society had a great ability to incorporate its one-time outsiders.[8]: 577

By this point, Burroughs was a counterculture icon. In his final years, he cultivated an entourage of young friends who replaced his aging contemporaries. In the 1980s he collaborated with performers ranging from Bill Laswell's Material and Laurie Anderson to Throbbing Gristle. Burroughs and R.E.M. collaborated on the song "Star Me Kitten" on the Songs in the Key of X: Music from and Inspired by the X-Files album. A collaboration with musicians Nick Cave and Tom Waits resulted in a collection of short prose, Smack My Crack, later released as a spoken-word album in 1987. In 1989, he appeared with Matt Dillon in Gus Van Sant's film, Drugstore Cowboy. In 1990, he released the spoken word album Dead City Radio, with musical backup from producers Hal Willner and Nelson Lyon, and alternative rock band Sonic Youth. He collaborated with Tom Waits and director Robert Wilson on The Black Rider, a play that opened at the Thalia Theatre in Hamburg in 1990 to critical acclaim, one that was later performed across Europe and the U.S. In 1991, with Burroughs's approval, director David Cronenberg adapted Naked Lunch into a feature film, which opened to critical acclaim.

During 1982, Burroughs developed a painting technique whereby he created abstract compositions by placing spray paint cans in front of blank surfaces, and then shooting at the paint cans with a shotgun. These splattered and shot panels and canvasses were first exhibited in the Tony Shafrazi Gallery in New York City in 1987. By this time he had developed a comprehensive visual art practice, using ink, spray paint, collage and unusual things such as mushrooms and plungers to apply the paint. He created file-folder paintings featuring these mediums as well as "automatic calligraphy" inspired by Brion Gysin. He originally used the folders to mix pigments before observing that they could be viewed as art in themselves. He also used many of these painted folders to store manuscripts and correspondence in his personal archive[67] Until his last years, he prolifically created visual art. Burroughs's work has since been featured in more than fifty international galleries and museums including Royal Academy of the Arts, Centre Pompidou, Guggenheim Museum, ZKM Karlsruhe, Sammlung Falckenberg, New Museum, Irish Museum of Modern Art, Los Angeles County Museum, and Whitney Museum of American Art.[68]

According to Ministry frontman Al Jourgensen, "We hung out at Burroughs's house one time in '93. So he decides to shoot up heroin and he takes out this utility belt full of syringes. Huge, old-fashioned ones from the '50s or something. Now, I have no idea how an 80 year old guy finds a vein, but he knew what he was doing. So we're all laying around high and stuff and then I notice in the pile of mail on the coffee table that there's a letter from the White House. I said 'Hey, this looks important.' and he replies 'Nah, it's probably just junk mail.' Well, I open the letter and it's from President Clinton inviting Burroughs to the White House for a poetry reading. I said 'Wow, do you have any idea how big this is!?' So he says 'What? Who's president nowadays?' and it floored me. He didn't even know who our current president was."[69]

In 1990, Burroughs was honored with a star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame.[70]

In June 1991, Burroughs underwent triple bypass surgery.[71]

He became a member of a chaos magic organization, the Illuminates of Thanateros, in 1993.[72]

He was a voice actor in the 1995 video game The Dark Eye based on the works of Edgar Allan Poe, in which he recites "Annabel Lee".

Burroughs's last filmed performance was in the music video for "Last Night on Earth" by Irish rock band U2, filmed in Kansas City, Missouri, directed by Richie Smyth and also featuring Sophie Dahl.[73]

Political beliefs

editThe only newspaper columnist Burroughs admired was Westbrook Pegler, a right-wing opinion shaper for the William Randolph Hearst newspaper chain.[8]: 170 Burroughs believed in frontier individualism, which he championed as "our glorious frontier heritage on minding your own business." Burroughs came to equate liberalism with bureaucratic tyranny, viewing government authority as a collective of meddlesome forces legislating the curtailment of personal freedom. According to his biographer Ted Morgan, his philosophy for living one's life was to adhere to a laissez-faire path, one without encumbrances – in essence a credo shared with the capitalist business world.[8]: 55 His abhorrence of the government did not prevent Burroughs from using its programs to his own advantage. In 1949 he enrolled in Mexico City College under the GI Bill, which paid for part of his tuition and books and provided him with a seventy-five-dollar-per-month stipend. He maintained, "I always say, keep your snout in the public trough."[8]: 173

Burroughs was a gun enthusiast and owned several shotguns, a Colt .45 and a .38 Special. Sonic Youth vocalist Thurston Moore recounted meeting Burroughs: "he had a number of Guns and Ammo magazines laying about, and he was only very interested in talking about shooting and knifing ... I asked him if he had a Beretta and he said: 'Ah, that's a ladies' pocket-purse gun. I like guns that shoot and knives that cut.'" Hunter S. Thompson gave him a one-of-a-kind .454 caliber pistol.[74] Burroughs was also a staunch supporter of the Second Amendment, being quoted as saying: "I sure as hell wouldn't want to live in a society where the only people allowed guns are the police and the military."[75]

Magical beliefs

editBurroughs had a longstanding preoccupation with magic and the occult, dating from his earliest childhood, and was insistent throughout his life that we live in a "magical universe".[76] As he himself explained:

In the magical universe there are no coincidences and there are no accidents. Nothing happens unless someone wills it to happen. The dogma of science is that the will cannot possibly affect external forces, and I think that's just ridiculous. It's as bad as the church. My viewpoint is the exact contrary of the scientific viewpoint. I believe that if you run into somebody in the street it's for a reason. Among primitive people they say that if someone was bitten by a snake he was murdered. I believe that.[77]

Or, speaking in the 1970s:

Since the word "magic" tends to cause confused thinking, I would like to say exactly what I mean by "magic" and the magical interpretation of so-called reality. The underlying assumption of magic is the assertion of "will" as the primary moving force in this universe – the deep conviction that nothing happens unless somebody or some being wills it to happen. To me this has always seemed self evident ... From the viewpoint of magic, no death, no illness, no misfortune, accident, war or riot is accidental. There are no accidents in the world of magic.[78]

His was not an idle interest: Burroughs practiced magic in his everyday life, seeking out mystical visions through practices like scrying,[79][80][48] taking measures to protect himself from possession,[81][82][35][36] and attempting to lay curses on those who had crossed him.[53][54][83] Burroughs spoke openly about his magical practices, and his engagement with the occult is attested by a number of interviews,[m][n][85] as well as personal accounts from those who knew him.[53][54][35]

Biographer Ted Morgan has argued: "As the single most important thing about Graham Greene was his viewpoint as a lapsed Catholic, the single most important thing about Burroughs was his belief in the magical universe. The same impulse that led him to put out curses was, as he saw it, the source of his writing ... To Burroughs behind everyday reality there was the reality of the spirit world, of psychic visitations, of curses, of possession and phantom beings."[8][86]

Burroughs insisted that his writing itself had a magical purpose.[o][p][q][r][91] This was particularly true when it came to his use of the cut-up technique. Burroughs was adamant that the technique had a magical function, stating "the cut ups are not for artistic purposes".[92] Burroughs used his cut-ups for "political warfare, scientific research, personal therapy, magical divination, and conjuration"[92] – the essential idea being that the cut-ups allowed the user to "break down the barriers that surround consciousness".[93] As Burroughs himself stated:

I would say that my most interesting experience with the earlier techniques was the realization that when you make cut-ups you do not get simply random juxtapositions of words, that they do mean something, and often that these meanings refer to some future event. I've made many cut-ups and then later recognized that the cut-up referred to something that I read later in a newspaper or a book, or something that happened ... Perhaps events are pre-written and pre-recorded and when you cut word lines the future leaks out.[93]

In the final decade of his life, Burroughs became heavily involved in the chaos magic movement. Burroughs's magical techniques – the cut-up, playback, etc. – had been incorporated into chaos magic by such practitioners as Phil Hine,[94][95][96] Dave Lee[97] and Genesis P-Orridge.[98][53] P-Orridge in particular had known and studied under Burroughs and Brion Gysin for over a decade.[53] This led to Burroughs contributing material to the book Between Spaces: Selected Rituals & Essays From The Archives Of Templum Nigri Solis[99] Through this connection, Burroughs came to personally know many of the leading lights of the chaos magic movement, including Hine, Lee, Peter J. Carroll, Ian Read and Ingrid Fischer, as well as Douglas Grant, head of the North American section of chaos magic group the Illuminates of Thanateros (IOT).[76][100] Burroughs's involvement with the movement further deepened, as he contributed artwork and other material to chaos magic books,[101] addressed an IOT gathering in Austria,[102] and was eventually fully initiated into the Illuminates of Thanateros.[s][103][76] As Burroughs's close friend James Grauerholz states: "William was very serious about his studies in, and initiation into the IOT ... Our longtime friend, Douglas Grant, was a prime mover."[100]

Death

editBurroughs died August 2, 1997, at age 83, in Lawrence, Kansas, from complications of a heart attack he had suffered the previous day.[19] He was interred in the family plot in Bellefontaine Cemetery in St. Louis, Missouri,[105] with a marker bearing his full name and the epitaph "American Writer". His grave lies to the right of the white granite obelisk of William Seward Burroughs I (1857–1898).

Posthumous works

editSince 1997, several posthumous collections of Burroughs's work have been published. A few months after his death, a collection of writings spanning his entire career, Word Virus, was published (according to the book's introduction, Burroughs himself approved its contents prior to his death). Aside from numerous previously released pieces, Word Virus also included what was promoted as one of the few surviving fragments of And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks, a novel by Burroughs and Kerouac. The complete Kerouac/Burroughs manuscript And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks was published for the first time in November 2008.[106]

A collection of journal entries written during the final months of Burroughs's life was published as the book Last Words in 2000. Publication of a memoir by Burroughs entitled Evil River by Viking Press has been delayed several times; after initially being announced for a 2005 release, online booksellers indicated a 2007 release, complete with an ISBN (ISBN 0-670-81351-6), but it remains unpublished.[107]

New enlarged or unexpurgated editions of numerous texts have been published in recent years as "Restored Text" or "Redux" editions all containing additional material and essays on the works or incorporating material edited out of previous versions. Beginning with Barry Miles and James Grauerholz's 2003 edition of Naked Lunch, followed by Oliver Harris's reconstructions of three trilogies of writings. The first of these are the early writings: Junky:the definitive text of "Junk" (2003), Queer: 25th-Anniversary Edition (2010) and The Yage Letters Redux (2006). Following the publication of the latter in December 2007, Ohio State University Press released Everything Lost: The Latin American Journals of William S. Burroughs also edited by Harris, the book contains transcriptions of journal entries made by Burroughs during the time of composing Queer and The Yage Letters, with cover art and review information. There followed "restored text" versions of some of Burroughs's best known novels The Soft Machine, The Ticket that Exploded and Nova Express (styled "the Cut Up Trilogy" officially here for the first time) from Penguin in 2014, and of Burroughs's more obscure collaborative poetic experiments of 1960 Minutes to Go: Redux and The Exterminator: Redux by Moloko Press in 2020. These books, originally pamphlets, are bulked out to three times their original size and the "trilogy" is complete with the completely new BATTLE INSTRUCTIONS an allied experimental collaboration, composited by Harris from unpublished drafts and recordings of the same period.

Literary style and periods

editBurroughs's major works can be divided into four different periods. The dates refer to the time of writing, not publication, which in some cases was not until decades later:

- Early work (early 1950s)

- Junkie, Queer and The Yage Letters are relatively straightforward linear narratives, written in and about Burroughs's time in Mexico City and South America.

- The cut-up period (mid-1950s to mid-1960s)

- Although published before Burroughs discovered the cut-up technique, Naked Lunch is a fragmentary collection of "routines" from The Word Hoard – manuscripts written in Tangier, Paris, London, as well as of other texts written in South America such as "The Composite City", blending into the cut-up and fold-in fiction also partly drawn from The Word Hoard: The Soft Machine, Nova Express, The Ticket That Exploded, also referred to as "The Nova Trilogy" or "The Cut-Up Trilogy", self-described by Burroughs as an attempt to create "a mythology for the space age". Interzone also derives from the mid-1950s.

- Experiment and subversion (mid-1960s to mid-1970s)

- This period saw Burroughs continue experimental writing with increased political content and branching into multimedia such as film and sound recording. Perhaps the defining and most important of which works is The Third Mind (with Brion Gysin) announced in 1966 and not published until the late '70s. The only major novels written in this period are The Wild Boys, and Port of Saints (republished in a different rewritten form in 1980, in the style Burroughs would adopt at that time). However, he also wrote dozens of published articles, short stories, scrap books and other works, several in collaboration with Brion Gysin. The major anthologies representing work from this period are The Burroughs File, The Adding Machine and Exterminator!.

- The Red Night trilogy (mid-1970s to mid-1980s)

- The books Cities of the Red Night, The Place of Dead Roads and The Western Lands came from Burroughs in a final, mature stage, creating a complete mythology.

Burroughs also produced numerous essays and a large body of autobiographical material, including a book with a detailed account of his own dreams (My Education: A Book of Dreams).

Reaction to critics and view on criticism

editSeveral literary critics treated Burroughs's work harshly. For example, Anatole Broyard and Philip Toynbee wrote devastating reviews of some of his most important books. In a short essay entitled "A Review of the Reviewers", Burroughs answers his critics in this way:

Critics constantly complain that writers are lacking in standards, yet they themselves seem to have no standards other than personal prejudice for literary criticism. ... such standards do exist. Matthew Arnold set up three criteria for criticism: 1. What is the writer trying to do? 2. How well does he succeed in doing it? ... 3. Does the work exhibit "high seriousness"? That is, does it touch on basic issues of good and evil, life and death and the human condition. I would also apply a fourth criterion ... Write about what you know. More writers fail because they try to write about things they don't know than for any other reason.

— William S. Burroughs, "A Review of the Reviewers"[108]

Burroughs clearly indicates here that he prefers to be evaluated against such criteria over being reviewed based on the reviewer's personal reactions to a certain book. Always a contradictory figure, Burroughs nevertheless criticized Anatole Broyard for reading authorial intent into his works where there is none, which sets him at odds both with New Criticism and the old school as represented by Matthew Arnold.

Photography

editBurroughs used photography extensively throughout his career, both as a recording medium in planning his writings, and as a significant dimension of his own artistic practice, in which photographs and other images feature as significant elements in cut-ups. With Ian Sommerville, he experimented with photography's potential as a form of memory-device, photographing and rephotographing his own pictures in increasingly complex time-image arrangements.[109]

Legacy

editBurroughs is often called one of the greatest and most influential writers of the 20th century, most notably by Norman Mailer whose quote on Burroughs, "The only American novelist living today who may conceivably be possessed by genius", appears on many Burroughs publications. Others consider his concepts and attitude more influential than his prose. Prominent admirers of Burroughs's work have included British critic and biographer Peter Ackroyd, the rock critic Lester Bangs, the philosopher Gilles Deleuze and the authors Michael Moorcock. J. G. Ballard, Angela Carter, Jean Genet, William Gibson, Alan Moore, Kathy Acker and Ken Kesey. Burroughs had an influence on the German writer Carl Weissner, who in addition to being his German translator was a novelist in his own right and frequently wrote cut-up texts in a manner reminiscent of Burroughs.[110]

Burroughs continues to be named as an influence by contemporary writers of fiction. Both the New Wave and, especially, the cyberpunk schools of science fiction are indebted to him. Admirers from the late 1970s – early 1980s milieu of this subgenre include William Gibson and John Shirley, to name only two. First published in 1982, the British slipstream fiction magazine Interzone (which later evolved into a more traditional science fiction magazine) paid tribute to him with its choice of name. He is also cited as a major influence by musicians Roger Waters, David Bowie, Patti Smith, Genesis P-Orridge,[111] Ian Curtis, Lou Reed, Laurie Anderson, Todd Tamanend Clark, John Zorn, Tom Waits, Gary Numan and Kurt Cobain.[112] A number of musical groups across a variety of genres use band names that are direct references to Burroughs' works, including Soft Machine, The Insect Trust, Steely Dan, two bands called Naked Lunch (a British band and an Austrian band, respectively), Interzone, Thin White Rope, Clem Snide, and Success Will Write Apocalypse Across the Sky.

In the film William S. Burroughs: A Man Within, Ira Silverberg commented on Burroughs's development as a writer:

Usually, the most radical work tends to come from the upper classes, because they're trying so hard to shop so hard to get away from their roots. So he's a fascinating character uniquely American in that regard. I don't think that work could have existed had he not been breaking away from an incredibly patrician Midwestern background.

Drugs, homosexuality, and death, common among Burroughs's themes, have been taken up by Dennis Cooper, of whom Burroughs said, "Dennis Cooper, God help him, is a born writer".[113] Cooper, in return, wrote, in his essay 'King Junk', "along with Jean Genet, John Rechy, and Ginsberg, [Burroughs] helped make homosexuality seem cool and highbrow, providing gay liberation with a delicious edge". Splatterpunk writer Poppy Z. Brite has frequently referenced this aspect of Burroughs's work. Burroughs's writing continues to be referenced years after his death; for example, a November 2004 episode of the TV series CSI: Crime Scene Investigation included an evil character named Dr. Benway (named for an amoral physician who appears in a number of Burroughs's works.) This is an echo of the hospital scene in the movie Repo Man, made during Burroughs's life-time, in which both Dr. Benway and Mr. Lee (a Burroughs pen name) are paged.

Burroughs had an impact on twentieth-century esotericism and occultism as well, most notably through disciples like Peter Lamborn Wilson and Genesis P-Orridge. Burroughs is also cited by Robert Anton Wilson as the first person to notice the "23 Enigma":

I first heard of the '23 Enigma' from William S. Burroughs, author of Naked Lunch, Nova Express, etc. According to Burroughs, he had known a certain Captain Clark, around 1960 in Tangier, who once bragged that he had been sailing 23 years without an accident. That very day, Clark's ship had an accident that killed him and everybody else aboard. Furthermore, while Burroughs was thinking about this crude example of the irony of the gods that evening, a bulletin on the radio announced the crash of an airliner in Florida, USA. The pilot was another Captain Clark and the flight was Flight 23.

— Robert Anton Wilson, Fortean Times[114]

Some research[115] suggests that Burroughs is arguably the progenitor of the 2012 phenomenon, a belief of New Age Mayanism that an apocalyptic shift in human consciousness would occur at the end of the Mayan Long Count calendar in 2012. Although never directly focusing on the year 2012 himself, Burroughs had an influence on early 2012 proponents such as Terence McKenna and Jose Argüelles, and as well had written about an apocalyptic shift of human consciousness at the end of the Long Count as early as 1960's The Exterminator.[116]

Burroughs appears on the cover of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, the iconic 1967 Beatles’ album. He is in the middle of the second row; see List of images on the cover of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.[117][118]

Bibliography

editFootnotes

edit- ^ "TV: So much of your work deals with the juncture between science and mystery, it seems. I mean there've been references to Orgone boxes, and Scientology, and Castaneda, it just goes on and on ... how did you get interested in this sort of area?

WB: Always was. I always was involved in that area from my early childhood. I was always interested in the occult and the mysterious ... just a life-long preoccupation." — William S. Burroughs, interviewed by Tom Vitale, November 26, 1986[12] - ^ "When I was four years old I saw a vision in Forest Park, St. Louis ... I was lagging behind and I saw a little green reindeer about the size of a cat ... Later, when I studied anthropology at Harvard, I learned that this was a totem animal vision and knew that I could never kill a reindeer." — William S. Burroughs[13]

- ^ "I was subject to hallucinations as a child. Once I woke up in the early morning light and saw little men playing in a block house I had made. I felt no fear, only a feeling of stillness and wonder." — William S. Burroughs[14]

- ^ "When Gysin, apparently in trance, told Burroughs 'The Ugly Spirit shot Joan because' he thought he finally had the answer ... the unforgiveable slip that had caused the death of his common-law wife, Joan Vollmer ... had come about because he was literally possessed by an evil spirit ... William instinctively knew the only solution available to him ... If the Word was indeed the basic mechanism of control – the 'virus' by which The Ugly Spirit, or its agency Control, exerted its malevolent influence – then surely a real understanding of the Word, what words are and what can be done with them – was essential. All these explorations and obsessions were not merely diversions, experiments for artistic or literary amusement ... but part of a deadly struggle with unseen, invisible – perhaps evil – psycho-spiritual enemies." — Stevens, Matthew Levi[32]

- ^ "The cut-up techniques made very explicit a preoccupation with exorcism – William's texts became spells, for instance." — Terry Wilson[33]

- ^ "The word of course is one of the most powerful instruments of control ... Now if you start cutting these up and rearranging them you are breaking down the control system." — William S. Burroughs[34]

- ^ "Burroughs often wrote about his belief in a 'magical universe.' ... Curses are real, possession is real. This struck him as a better model for human experience and psychology than the neurosis theories of Freud, in the end ... he did pursue a lifelong quest for spiritual techniques by which to master his unruly thoughts and feelings, to gain a feeling of safety from oppression and assault from without, and from within."[35]

- ^ "Once I looked in a mirror and saw my hands completely inhuman, thick, black-pink, fibrous, long white tendrils growing from the curiously abbreviated finger-tips as if the finger have been cut off to make way for tendrils." — William S. Burroughs, Letter to Allen Ginsberg, January 2, 1959[47]

- ^ "What is happening is that I literally turn into someone else, not a human creature but man-like: He wears some sort of green uniform. The face is full of black boiling fuz and what most people would call evil – silly word. I have been seeing him for some time in the mirror." — William S. Burroughs, Letter to Allen Ginsberg, late July 1959[47]

- ^ "The Para-normal occurrences thick and fast ... I saw Stern lose about seven pounds in ten minutes ... On another occasion he felt my touch on his arm across six feet of space." — William S. Burroughs, Letter to Allen Ginsberg, January 2, 1959[47]

- ^ "William continued going to the bar for a few more days, enduring their abuse, while he tape recorded the sounds inside. Later, he would stand outside and film or photograph the premises from outside. Then he went back in and began to play the tape recordings at low or subliminal levels, and continued to take photographs on his way in and out of the place ... The effects were remarkable: accidents occurred, fights broke out, the place lost customers, the subsequent loss of income became irredeemable, and within a few weeks, the bar was permanently closed." — Cabell McLean[54]

- ^ " ... Burroughs also made similarly sorcerous attempts that same year against the London HQ of Scientology at 37 Fitzroy Street. Although he considered it another success when they closed down, he seemed unable to bring any 'playback' influence to bear on their new location in Tottenham Court Road." — M.L. Stevens[55]

- ^ "Interviewer: You're interested in the occult, aren't you?

Burroughs: Certainly. I'm interested in the golden dawn, Aleister Crowley, all the astrological aspects." — William S. Burroughs[84] - ^ "I will speak now for magical truth to which I myself subscribe. Magic is the assertion of will, the assumption that nothing happens in this universe (that is to say the minute fraction of the universe we are able to contact) unless some entity wills it to happen." — William S. Burroughs

- ^ "It is to be remembered that all art is magical in origin – music sculpture writing painting – and by magical I mean intended to produce very definite results ..." — William S. Burroughs[87]

- ^ "I will examine the connections between so-called occult phenomena and the creative process. Are not all writers, consciously or not, operating in these areas?" — William S. Burroughs[88]

- ^ "JT: Rather than simply informing us of a vision of the future, as in The Wild Boys, I feel the ultimate end of your fiction is a kind of alchemy – magic based on precise and incantatory arrangement of language to create particular effects, such as the violation of Western conditioning.

WB: I would say that that was accurate ... Of course the beginning of writing, and perhaps of all art, was related to the magical. Cave painting, which is the beginning of writing ... The purpose of those paintings was magical, that is to produce the effect that is depicted." — William S. Burroughs[89] - ^ "NZ: Your work often seems more primitive, ritualistic or magical perhaps.

WB: It's supposed to be, yes. It's supposed to have an element of magical invocation." — William S. Burroughs[90] - ^ "William ... was subsequently initiated into the IOT, by myself and another Frater and Soror. William did not receive an honorary degree, he was put through an evening of ritual that included a Retro Spell Casting Rite, and Invocation of Chaos, and a Santeria Rite, as well as the Neophyte Ritual inducting William into the IOT as a full member ... Though it is not included in the list of items buried with William, James Grauerholz assured me that William was buried with his IOT Initiate ring." — D. Grant (2003)

References

edit- ^ a b Lawlor, William (2005). Beat Culture: Lifestyles, icons, and impact. ABC-CLIO. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-85109-400-4.

- ^ Severo, Richard (August 3, 1997). "William S. Burroughs Dies at 83; Member of the Beat Generation Wrote 'Naked Lunch'". The New York Times. Retrieved August 28, 2021.

- ^ Campbell, James (August 4, 1997). "Struggles with the Ugly Spirit". the Guardian. Retrieved August 28, 2021.

- ^ a b Stevens, Matthew Levi (2014). The Magical Universe of William S. Burroughs. Mandrake of Oxford.

- ^ Jones, Josh (September 14, 2012). "William S. Burroughs Shows You How to Make "Shotgun Art"". Open Culture. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

There is no exact process. If you want to do shotgun art, you take a piece of plywood, put a can of spray paint in front of it, and shoot it with a shotgun or high powered rifle.

- ^ El Nacional, September 8, 1951

- ^ La Prensa, September 8, 1951

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Morgan, Ted (1988). Literary Outlaw: The life and times of William S. Burroughs. New York: Avon. ISBN 0-8050-0901-9 – via Google Books; re-published Morgan, Ted (2012) [1988]. Literary Outlaw. W.W. Norton & Company.

- ^ Biography, The Guardian

- ^ a b Naked Lunch: The Restored Text, Harper Perennial Modern Classics (2005). It includes an introduction by J. G. Ballard and an appendix of biography and reference to further reading: "About the author", "About the book", and "Read on".

- ^ Burroughs, 2003. Penguin Modern Classics edition of Junky.

- ^ Transcript published as A Moveable Feast in Burroughs Live: The Collected Interviews of William S. Burroughs 1960–1997 2001.

- ^ Burroughs, 1992. The Cat Inside. Viking.

- ^ Burroughs, 1977, Junky, prologue. Penguin.

- ^ "William S Burroughs". Popsubculture.com. Biography.

- ^ a b Grauerholz, James; Silverberg, Ira; Douglas, Ann, eds. (2000). Word Virus: The William S. Burroughs Reader. New York City: Grove Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0802136947.

- ^ Staff, Flavorwire (February 4, 2011). "97 Things you didn't know about William S. Burroughs". Flavorwire. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ a b 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ a b Severo, Richard (August 3, 1997). "William S. Burroughs Dies at 83; Member of the Beat Generation Wrote 'Naked Lunch'". The New York Times. Retrieved October 22, 2007.

- ^ Grauerholz, James. Introduction p. xv, in William Burroughs. Interzone. New York: Viking Press, 1987.

- ^ Johnson, Joyce (2012). The Voice is All: The lonely victory of Jack Kerouac. Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-670-02510-7.

- ^ a b Grauerholz, James; Silverberg, Ira (December 1, 2007). Word Virus: The William S. Burroughs Reader. Grove Press. p. 42.

- ^ Latvala, Maureen (August 22, 2005). "Joan Vollmer". Women of the Beat.org. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007.

- ^ "William S. Burroughs". 64parishes. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ a b Severo, Richard (August 4, 1997). "William S. Burroughs, the beat writer who distilled his raw nightmare life, dies at 83". The New York Times. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ Grauerholz, James (December 9, 2003). "The death of Joan Vollmer-Burroughs: What really happened?". lawrence.com. American Studies Department, University of Kansas. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

- ^ Snowden, Lynn (February 1992). "Which is the fly and which is human?". Esquire. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ "Heir's pistol kills his wife; he denies playing Wm. Tell". Associated Press. September 7, 1951. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ "Burroughs: The Movie". Janus Films.

- ^ a b Queer, Penguin, 1985, p. xxiii.

- ^ Stevens, Matthew Levi. The Magical Universe of William S. Burroughs. p.125.

- ^ Stevens, Matthew Levi. The Magical Universe of William S. Burroughs. pp. 124–125.

- ^ Terry Wilson in conversation with Brion Gysin. Ports of Entry, published in Here to go: planet R-101 (1982). Re/Search Publications.

- ^ interviewed by Daniel Odier. Journey through space-time, published in The Job (1970). John Calder Ltd.

- ^ a b c James Grauerholz, On Burroughs and Dharma, Summer Writing Institute, June 24, 1999, Naropa University. Transcript published in Beat Scene Magazine, No.71a, Winter 2014.

- ^ a b William S. Burroughs, interviewed by Allen Ginsberg (1992). Published as The Ugly Spirit in Burroughs Live: The Collected Interviews of William S. Burroughs 1960–1997. 2001.

- ^ James Grauerholz. Word Virus, New York: Grove, 1998.

- ^ a b "William S. Burroughs." Biography.com.

- ^ Bill Morgan, 2006. I Celebrate Myself, New York: Viking Press, p. 159.

- ^ James Grauerholz writes, in Interzone, the body of text that Burroughs was working on was called Interzone, see Burroughs, William S. Interzone. "Introduction", pp. ix–xiii. New York: Viking Press, 1987.

- ^ Miles, Barry (2003). "The Inventive Mind of Brion Gysin". In Kuri, José Férez (ed.). Brion Gysin: Tuning in to the Multimedia Age. London, England: Thames and Hudson. pp. 124–125. ISBN 978-0500284384.

- ^ Burroughs, William S., Ports of Entry – Here is Space-Time Painting, p.32.

- ^ Ginsberg, Allen. Postcard to John Ciardi. July 11, 1959. MS. Stuart Wright Collection: Richard Ghormley Eberhart Papers. Joyner Lib., Greenville, North Carolina.

- ^ Baker, P., William S. Burroughs (London: Reaktion Books, 2010), p. 118.

- ^ Grauerholz, James. Introduction p. xviii, in William Burroughs. Interzone. New York: Viking Press, 1987.

- ^ Stevens, Matthew Levi. The Magical Universe of William S. Burroughs. p.50.

- ^ a b c The Letters of William S. Burroughs, 1945 to 1959. Viking Penguin, 1993.

- ^ a b William S. Burroughs, letter to Brion Gysin, January 17, 1959. The Letters of William S. Burroughs, 1945 to 1959. Viking Penguin, 1993.

- ^ "My Own Mag – RealityStudio".

- ^ Dent, John Yerbury. Anxiety and Its Treatment. London: J. Murray, 1941.

- ^ Burroughs, William, S. "Afterword". Speed/Kentucky Ham: Two Novels. New York: Overlook Press, 1984.

- ^ Lee Hill A Grand Guy: The Art and Life of Terry Southern.

- ^ a b c d e P-Orridge, Genesis. Magick Squares and Future Beats

- ^ a b c McLean, Cabell (2003). "Playback: My experience of chaos magic with William S. Burroughs, Sr". Ashé Journal of Experimental Spirituality. Vol. 2, no. 3.

- ^ Stevens, Matthew Levi. The Magical Universe of William S. Burroughs. p.129.

- ^ William S. Burroughs, Playback From Eden to Watergate, published in The Job. John Calder Ltd.

- ^ David S. Wills, "The Weird Cult: William S. Burroughs and Scientology", Beatdom Literary Journal, December 2011.

- ^ Burroughs on Scientology, Los Angeles Free Press, March 6, 1970.

- ^ "222 Bowery · 222 Bowery, New York, NY 10012, USA". 222 Bowery · 222 Bowery, New York, NY 10012, USA.

- ^ Bockris, V. With William Burroughs: A Report From the Bunker. New York: St. Martin's Griffin, 1996.

- ^ "William Burroughs at 100: Thurston Moore on seeing him watch Patti Smith at CBGB, his response to Kurt Cobain's suicide and 'cut-up' songwriting". February 5, 2014.

- ^ Marzoni, A., "Precarious Immortality: William S. Burroughs on Film", ARTnews, December 8, 2015.

- ^ Palmer, R., "The Pop Life", The New York Times, March 18, 1977.

- ^ Charters, Ann. "Introduction". Speed/Kentucky Ham: Two Novels. New York: Overlook Press, 1984.

- ^ Burroughs, William. "Introduction". Last Words: The Final Journals of William S. Burroughs. New York: Grove Press, 2000.

- ^ "Godfather of Beat Generation was content to live last days in Kansas" Archived December 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Wichita Eagle and Kansas.com, April 5, 2010.

- ^ "Riflemaker Contemporary Art | The Riflemaker Gallery |". www.riflemaker.org.

- ^ "William Burroughs Biography", October Gallery.

- ^ Jourgensen, Al & Wiederhorn, Jon (July 9, 2013). Ministry: The Lost Gospels according to Al Jourgensen. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-82218-6 – via Internet Archive. Includes the discography section on pp. 275-278. Between pp. 128 and 129 there are 12 pages of pictures.