A veche[a] was a popular assembly during the Middle Ages. The veche is mentioned during the times of Kievan Rus' and it later became a powerful institution in Russian cities such as Novgorod and Pskov,[1] where the veche acquired great prominence and was broadly similar to the Norse thing or the Swiss Landsgemeinde.[2] The last veche meeting was held in Pskov before the institution was abolished in 1510.[3]

Etymology

editThe word veche is a transliteration of the Russian "вече" (pl. веча, vecha), which is in turn inherited from Proto-Slavic *vě̑ťe (lit. 'council, counsel' or 'talk'), which is also represented in the word soviet, both ultimately deriving from the Proto-Slavic verbal stem of *větiti 'to talk, speak').[1]

History

editOrigins

editProcopius of Caesarea mentioned Slavs gathering in popular assemblies in the 6th century:[4]

But when the report was carried about and reached the entire nation, practically all the Antae assembled to discuss the situation, and they demanded that the matter be made a public one(...). For these nations, the Sclaveni and the Antae, are not ruled by one man, but they have lived from of old under a democracy, and consequently everything which involves their welfare, whether for good or ill, is referred to the people.[5]

The veche is thought to have originated in the tribal assemblies of Eastern Europe, thus predating the state of Kievan Rus'.[6][7][8] Although most authors have adopted this view, the evidence is not abundant and is mainly based on the statement of Procopius and a few other communications from foreign authors such as Byzantine emperor Maurice's Strategikon, as well as a few chronicle mentions.[8] The Poliane in Kiev, according to the Primary Chronicle, are said to have consulted among themselves (s"dumavshe poliane) before deciding to ultimately pay tribute to the Khazars.[4] The words duma and dumati are used in later instances to refer to the activities of the veche.[4] The Primary Chronicle also indicates the recognition of the people as a separate political agent in a 944 treaty with the Byzantine Empire: "And our grand prince Igor and his boyars, and the whole people of Rus have sent us".[4]

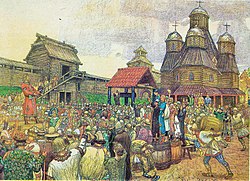

The earliest mentions of the veche in chronicles refer to examples in Belgorod in 997,[9] Novgorod in 1016,[10] and Kiev in 1068.[11] A central role of the veche is found in the Suzdal Chronicle under the year 1176: "From of old the people of Novgorod, of Smolensk, of Kiev, of Polotsk, and of all the lands have assembled for counsel in veches".[11] Some scholars have used this quote in their argument that the veche was a universal occurrence and has immemorial origins.[11] The assemblies discussed matters of war and peace, adopted laws, and called for and expelled rulers. In Kiev, the veche was summoned in front of the Cathedral of St. Sophia.

The majority of references to veche meetings during the Kievan period is connected with dynastic crises.[12] There are not many references of a veche in towns in the 11th century, but there are significantly more in the 12th century, with such references mostly concerning Novgorod and Pskov.[4][13] Medieval chronicles, such as the Primary Chronicle, and the Novgorod First Chronicle for Novgorod especially, are the basic source regarding the veche.[4] The Primary Chronicle remains the main source for the early history of Kievan Rus', but its narrative ends at 1116.[14] The next generation of chronicles, including the Suzdal Chronicle, are also important sources.[4] Following the Mongol invasions, most references concern Novgorod and Pskov.[14]

Russia

editMost of the information about the veche concerns the 13th to 15th centuries.[15] For veche proceedings, the veche had to be convoked first, often by the prince, but the main topic of the meeting usually was about a conflict between the prince and the population.[15] As a result, there was no regular procedure to be followed, which often led to violence among the participants.[16] There are several mentions of the prince being deposed and the crowd pillaging the residence of the prince.[16] Not much is known about actual proceedings except that the bishop could function as the chairman, while in other instances, the prince could assume this role.[15] The chronicles also mention the existence of a veche bell in not only Novgorod and Pskov, but also in Vladimir.[16] Almost all that is known about treaty-making activities of towns concerns Novgorod, and to a lesser extent, Pskov.[17]

During Tatar rule, there was little room for veche independence.[18] The cities in the northwest were less affected by Tatar overlordship, and so the institution survived longer there.[19] In 1262, veche meetings were held in Rostov, Suzdal, Vladimir and Yaroslavl, in which it was decided to throw out the tax collectors sent by the Tatars.[18] In 1304, the citizens of Kostroma and Nizhny Novgorod rebelled against the local aristocracy at the veche meetings.[18] There is also a final mention of a veche meeting in Moscow in 1382, when Tokhtamysh had launched a campaign against Dmitry Donskoy.[18] The latter had fled to Kostroma while the former had captured Serpukhov near the city of Moscow.[18] Nikolay Karamzin said that the people of Moscow "at the sound of the bells assembled for a veche, remembering the ancient right of the Russian citizens to decide their own fate in important situations by a majority of votes".[18]

Vladimir-Suzdal

editA semi-legendary account of Aleksandr of Suzdal (r. 1309–1331) moving the veche bell from Vladimir to his appanage center Suzdal during his reign as grand prince is found in chronicles:[20][21]

This Prince Alexander from Vladimir took the veche bell from the Church of the Holy Mother of God to Suzdal and the bell ceased to ring as in Vladimir. And Prince Alexander thought he had been rude to the Holy Mother of God, and he ordered it taken back to Vladimir. And when the bell was brought back and installed in its place, its peal once again became acceptable to God.[21]

— Novgorod First Chronicle

Novgorod Republic

editThe Novgorod veche was the highest legislative and judicial authority in the city until 1478, after Novgorod was formally annexed by Ivan III.[22] Each of the kontsy (boroughs or "ends") of Novgorod also had their own veche to elect borough officials.[13] The veche for the city selected the prince, posadnik and archbishop.[13]

Historians debate whether the Novgorod veche consisted of entirely free males or was instead dominated by a small group of nobles known as boyars.[13] The Novgorod veche grew to become more structured in a way that it could be compared to similar bodies in Italian and Flemish towns during the same period.[23] Traditional scholarship argues that a series of reforms in 1410 transformed the veche into something similar to the public assembly (Concio) of the Republic of Venice; it became the lower chamber of the parliament. An upper chamber knowns as the Council of Lords (sovet gospod) was also created which oversaw the veche,[13] with title membership for all former city magistrates (posadniki and tysyatskiye). Some sources indicate that veche membership may have become full-time, and parliament deputies were now called vechniki. Some recent scholars call this interpretation into question.

The Novgorod veche could be presumably summoned by anyone who rang the veche bell, although it is more likely that the common procedure was more complex. The whole population of the city, including boyars, merchants, and common citizens, then gathered in front of the Cathedral of Saint Sophia or at Yaroslav's Court on the Trade Side.[13]

Of all other towns of Novgorod Land, the chronicles only mention a veche in Torzhok; however they possibly existed in all other towns as well.[24][25]

Pskov Republic

editThe veche of the Pskov Land and later Pskov Republic had legislative powers; it could appoint military commanders and hear ambassadors' reports. It also approved expenses such as grants to princes and payments to builders of walls, towers and bridges.[26] The veche gathered at the court of the Trinity Cathedral, which held the archives of the veche and important private papers and state documents. The veche assembly included posadniki (mayors), "middle" and common people.[27] Historians differ on the extent to which the veche was dominated by the elites, with some saying that real power was held in the hands of boyars, with others considering the veche to be a democratic institution.[28] Conflicts were common and the confrontation between the veche and the posadniki in 1483–1484 led to the execution of one posadnik and the confiscation of the property of three other posadniki who fled to Moscow.[29] The most significant achievement of the Pskov veche was the adoption of the Pskov Judicial Charter, likely after 1462, which was the most comprehensive Russian legislation enacted until the Sudebnik of 1497 under Ivan III, the first collection of laws of the unified state.[23]

In the autumn of 1509, Grand Prince Vasily III visited Novgorod, where he received complaints from the Pskov veche against the Muscovite governor of the city.[30] At first, Vasily encouraged complaints against the governor, but soon demanded that the city abolish its traditional institutions, including the removal of the veche bell.[30] From that point on, Pskov was to be ruled exclusively by his governors and officials, and on 13 January 1510, the veche bell was removed and transported to Moscow.[30]

Poland

editThe veche, known in Poland as wiec, were convened even before the beginning of the Polish statehood in the Kingdom of Poland.[31] Issues were first debated by the elders and leaders, and later presented to all the free men for a wider discussion.[31][32]

One of the major types of wiec was the one convened to choose a new ruler.[31] There are legends of a 9th-century election of the legendary founder of the Piast dynasty, Piast the Wheelwright, and a similar election of his son, Siemowit, but sources for that time come from the later centuries and their validity is disputed by scholars.[33][34] The election privilege was usually limited to the elites,[31] which in the later times took the form of the most powerful nobles (magnates, princes) or officials, and was heavily influenced by local traditions and strength of the ruler.[35] By the 12th or 13th century, the wiec institution likewise limited its participation to high ranking nobles and officials.[32] The nationwide gatherings of wiec officials in 1306 and 1310 can be seen as precursors of the Polish parliament (the General Sejm).[32]

See also

edit- Zemsky Sobor, Russian parliament from the early modern period

- Duma, a type of Russian assembly

- Landsgemeinde, a Swiss assembly

- Thing in Scandinavia, Sejm in Poland, Seimas in Lithuania, Saeima in Latvia

- Rada, a later kind of popular assembly, then the parliament of Ukraine

Notes

edit- ^ Russian: ве́че, romanized: veche, IPA: [ˈvʲet͡ɕe]; Polish: wiec, IPA: [vjɛt͡s] ; Ukrainian: ві́че, romanized: víče, IPA: [ˈʋ⁽ʲ⁾it͡ʃe] ; Belarusian: ве́ча, romanized: viéča, IPA: [ˈvʲɛt͡ʂa]; Church Slavonic: вѣще, romanized: věšte

- ^ See the Slavic etymology of the word and the corresponding references in the following entries of the Max Vasmer's Etymological dictionary:

- of the particular word вече/veche (in Russian),

- of the basic root вѣт- (in Russian),

- and the possible further Indo-European etymology of this root in the entry

- all of them presented online in the etymological databases of The Tower of Babel project.

References

edit- ^ "veche (medieval Russian assembly) - Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ Københavns universitet. Polis centret (2000). A Comparative Study of Thirty City-state Cultures: An Investigation. Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskab. pp. 268–. ISBN 978-87-7876-177-4. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ Feldbrugge 2009, p. 250.

- ^ a b c d e f g Feldbrugge 2017, pp. 415–418.

- ^ All the Slavs of Procopius, In Nomine Jassa

- ^ "Вече". Hist.msu.ru. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ veche. 2010). Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ a b Feldbrugge 2017, p. 421.

- ^ Feldbrugge 2017, p. 416.

- ^ Feldbrugge 2009, p. 147.

- ^ a b c Feldbrugge 2017, p. 417.

- ^ Feldbrugge 2009, p. 151.

- ^ a b c d e f Langer, Lawrence N. (15 September 2021). Historical Dictionary of Medieval Russia. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 234. ISBN 978-1-5381-1942-6.

- ^ a b Feldbrugge 2009, p. 148.

- ^ a b c Feldbrugge 2017, p. 429.

- ^ a b c Feldbrugge 2009, p. 157.

- ^ Feldbrugge 2017, p. 432.

- ^ a b c d e f Feldbrugge 2009, p. 158.

- ^ Feldbrugge 2009, p. 159.

- ^ Pudalov, B. M. (2004). Русские земли Среднего Поволжья (вторая треть XIII – первая треть XIV в.) [Russian lands of the Middle Volga region (second third of the 13th to first third of the 14th centuries)] (in Russian). Nizhny Novgorod: Комитет по делам архивов Нижегородской области. ISBN 5-93413-023-4.

- ^ a b Tikhomirov, Mikhail N. (1959). The Towns of Ancient Rus. Foreign Languages Publishing House. p. 227.

- ^ Feldbrugge 2009, pp. 147–165.

- ^ a b Feldbrugge 2009, p. 160.

- ^ Kostomarov, Nikolay (2013). Russkaya Respublika Русская республика (Севернорусские народоправства во времена удельно-вечевого уклада. История Новгорода, Пскова и Вятки) (in Russian). Pubmix.com. p. 213. ISBN 9785424117350.

- ^ Stepnyak-Kravchinsky, Sergey (2013). Россия под властью царей (in Russian). Pubmix.com. p. 18. ISBN 9785424119651.

- ^ Kafengauz, Berngardt (1969). Древний Псков. Очерки по истории феодальной республики (in Russian). Nauka. pp. 98–105.

- ^ Kafengauz, Berngardt (1969). Древний Псков. Очерки по истории феодальной республики (in Russian). Nauka. p. 111.

- ^ Kafengauz, Berngardt (1969). Древний Псков. Очерки по истории феодальной республики (in Russian). Nauka. pp. 85–90, 110.

- ^ Kafengauz, Berngardt (1969). Древний Псков. Очерки по истории феодальной республики (in Russian). Nauka. p. 74.

- ^ a b c Crummey 2014, p. 92.

- ^ a b c d Juliusz Bardach, Bogusław Leśnodorski, and Michał Pietrzak, Historia państwa i prawa polskiego (Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1987, p.20, 26-27

- ^ a b c Juliusz Bardach, Bogusław Leśnodorski, and Michał Pietrzak, Historia państwa i prawa polskiego (Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1987, p.63-64

- ^ Norman Davies (23 August 2001). Heart of Europe: The Past in Poland's Present. Oxford University Press. p. 249. ISBN 978-0-19-280126-5. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Janusz Roszko (1980). Kolebka Siemowita. Iskry. p. 170. ISBN 978-83-207-0090-9. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Juliusz Bardach, Bogusław Leśnodorski, and Michał Pietrzak, Historia państwa i prawa polskiego (Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1987, p.62-63

Sources

edit- Crummey, Robert O. (6 June 2014). The Formation of Muscovy 1300 - 1613. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-87199-6.

- Feldbrugge, Ferdinand J. M. (2 October 2017). A History of Russian Law: From Ancient Times to the Council Code (Ulozhenie) of Tsar Aleksei Mikhailovich of 1649. BRILL. pp. 415–418. ISBN 978-90-04-35214-8.

- Feldbrugge, Ferdinand Joseph Maria (2009). Law in Medieval Russia. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-16985-2.