Westminster Cathedral, formally the Metropolitan Cathedral of the Most Precious Blood of Our Lord Jesus Christ, is the largest Roman Catholic church in England and Wales and the seat of the Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster.

| Westminster Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| Metropolitan Cathedral of the Most Precious Blood of Our Lord Jesus Christ | |

Cathedral from Victoria Street | |

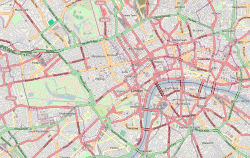

| 51°29′46″N 0°08′23″W / 51.4961°N 0.1397°W | |

| OS grid reference | TQ 29248 79074 |

| Location | Francis Street, Westminster London, SW1 |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Website | westminstercathedral |

| History | |

| Status | Cathedral |

| Dedication | Most Precious Blood |

| Consecrated | 1910 |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | John Francis Bentley |

| Style | Neo-Byzantine |

| Years built | 1895–1903 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 110m (360ft) |

| Width | 47m (156ft) |

| Number of towers | 1 |

| Tower height | 87m (284ft), including the cross |

| Administration | |

| Province | Westminster |

| Diocese | Westminster (since 1884) |

| Clergy | |

| Archbishop | Vincent Nichols |

| Dean | Slawomir Witon |

| Laity | |

| Organist(s) | Simon Johnson, Peter Stevens |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Designated | 1 December 1987 Amended 15 February 1994 |

| Reference no. | 1066500[1] |

The site on which the cathedral stands in the City of Westminster was purchased by the Diocese of Westminster in 1885, and construction was completed in 1903.[2] Designed by John Francis Bentley in a 9th-century Christian neo-Byzantine style, and accordingly made almost entirely of brick, without steel reinforcements,[3][4] Sir John Betjeman called it "a masterpiece in striped brick and stone" that shows "the good craftsman has no need of steel or concrete."[5]

History

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2022) |

In the late 19th century, the Roman Catholic Church's hierarchy had only recently been restored in England and Wales, and it was in memory of Cardinal Wiseman (who died in 1865, and was the first Archbishop of Westminster from 1850) that the first substantial sum of money was raised for the new cathedral. The land was acquired in 1884 by Wiseman's successor, Cardinal Manning, having previously been occupied by the second Tothill Fields Bridewell prison.

After two false starts, in 1867 (under architect Henry Clutton) and 1892 (architect Baron von Herstel), construction started in 1895 under Manning's successor, the third archbishop, Cardinal Vaughan, with John Francis Bentley as architect, in a style heavily influenced by Byzantine architecture.[6] The cost of the building was anticipated at £150,000 and its area 54,000 sq ft, the cathedral to be 350 ft long by 156 ft wide by 90 ft high.[7]

The foundation stone blessing by Cardinal Vaughan took place on a Saturday morning, 29 June 1895, before a "distinguished" gathering. After the "recitation of the Litanies, Cardinal Logue celebrated Low Mass coram episcopo. A procession composed of Benedictines, Franciscans, Jesuits, Passionists, Dominicans, Redemptorists, and secular clergy made the circuit of the grounds. The choir, directed by the Rev. Charles Cox, rendered, among other pieces, Webbe's 'O Roma Felix' and 'O Salutaris'. At the luncheon which followed, the speakers included Cardinal Vaughan, Cardinal Logue, the Duke of Norfolk, Lord Acton, Henry Matthews MP, Lord Edmund Talbot, and Sir Donald Macfarlane."[8]

The cathedral opened in 1903, a year after Bentley's death. One of the first public liturgies to be celebrated in the cathedral was Cardinal Vaughan's Requiem Mass; the Cardinal died on 19 June 1903.[9] When the debt on the building fund was liquidated, consecration ceremony took place on 28 June 1910[10] Under the laws of the Catholic Church, no place of worship could be consecrated unless free from debt.

The decoration of the interior had hardly been started at the time of consecration, as the decoration in Byzantine churches is applied, rather than integral to the architecture. Therefore finishing the decoration of the cathedral was left to the subsequent generations. It is an architectural gem with its interior notable for rich marble decorations and the beautiful, but still incomplete, mosaics.

In 1895, the cathedral was dedicated to the Most Precious Blood of Our Lord Jesus Christ. This is indicated by the Latin dedication above the portal arch: Domine Jesus Rex et Redemptor per Sanguinem tuum salva nos (English translation: "Lord Jesus, King and Redeemer, heal us through your blood"). The additional patrons are St Mary, the mother of Jesus, St Joseph, his foster father, and St Peter, his vicar. The cathedral also has numerous secondary patrons: St Augustine and all British saints, St Patrick and all saints of Ireland.[11] The Feast of the Dedication of the Cathedral is celebrated each year on 1 July,[11] which from 1849 until 1969 was the feast of the Most Precious Blood of Our Lord Jesus Christ.

In 1977, as part of her Silver Jubilee Celebrations, Queen Elizabeth II visited the cathedral to view a flower show.

On 28 May 1982, the first day of his six-day pastoral visit to the United Kingdom, Pope John Paul II celebrated Mass in the cathedral.

On St Andrew's Day (30 November) 1995, at the invitation of Basil Cardinal Hume, Queen Elizabeth again visited the cathedral but this time she attended Choral Vespers, the first participation of the Queen in a Roman Catholic church liturgy in Great Britain.

On 18 September 2010, on the third day of his four-day state visit to the United Kingdom, Pope Benedict XVI celebrated Mass in the cathedral.

In January 2011 the cathedral was the venue for the reception and later ordination of three former Anglican bishops[12] into the newly formed Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham.

In 2012, the cathedral was the host of two episodes of the BBC Four three-part documentary series named Catholics: the first episode looked at women who attend and/or work at the cathedral and their faith, and the third episode looked at the men training to become priests at Allen Hall seminary, and in the episode was a brief scene of their ordination at the cathedral.

In May 2021, during the Covid Pandemic and the banning of public mass, Prime Minister Boris Johnson and Carrie Symonds were wed at the Cathedral.[13]

Architecture

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2015) |

Westminster Cathedral is the 50th largest church in the world in terms of interior area (5,017m²), seating up to 2,000 people. It is the 38th largest Catholic church globally in terms of interior area.

The whole building, in the neo-Byzantine style, covers a floor area of about 5,017 square metres (54,000 sq ft); the dominating factor of the scheme, apart from the campanile, being a spacious and uninterrupted nave, 18 metres (59 ft) wide and 70 metres (230 ft) long from the narthex to the sanctuary steps,[14] covered with domical vaulting.

In planning the nave, a system of supports was adopted not unlike that to be seen in most Gothic cathedrals, where huge, yet narrow, buttresses are projected at intervals, and stiffened by transverse walls, arcading and vaulting. Unlike in a Gothic cathedral, at Westminster they are limited to the interior. The main piers and transverse arches that support the domes divide the nave into three bays, each about 395 square metres (4,250 sq ft). The domes rest on the arches at a height of 27 metres (89 ft) from the floor, the total internal height being 34 metres (112 ft).

In selecting the pendentive type of dome, of shallow concavity, for the main roofing, weight and pressure have been reduced to a minimum. The domes and pendentures are formed of concrete, and as extraneous roofs of timber were dispensed with, it was necessary to provide a thin independent outer shell of impervious stone. The concrete flat roofing around the domes is covered with asphalt. The sanctuary is essentially Byzantine in its system of construction. The extensions that open out on all sides make the corona of the dome seem independent of support.

The eastern termination of the cathedral suggests the Romanesque, or Lombardic style of Northern Italy. The crypt with openings into the sanctuary, thus closely following the Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio, Milan, the open colonnade under the eaves, the timber roof following the curve of the apex, are all familiar features. The large buttresses resist the pressure of a vault 14.5-metre (48 ft) in span. Although the cruciform plan is not very noticeable inside the building, it is emphasised outside by the boldly projecting transepts. These with their twin gables, slated roofs, and square turrets with pyramidal stone cappings suggest a Norman prototype in striking contrast to the rest of the design.

The main structural parts of the building are of brick and concrete, the latter material being used for the vaulting and domes of graduated thickness and complicated curve. Following Byzantine tradition, the interior was designed with a view to the application of marble and mosaic. Throughout the exterior, the lavish introduction of white stone bands in connection with the red brickwork (itself quite common in the immediate area) produces an impression quite foreign to the British eye. The bricks were hand-moulded and delivered by Faversham Brickfields at Faversham in Kent and Thomas Lawrence Brickworks in Bracknell.[15] The main entrance façade owes its composition, in a measure, to accident rather than design. The most prominent feature of the façade is the deeply recessed arch over the central entrance, flanked by tribunes, and stairway turrets. The elevation on the north, with a length of nearly 91.5 metres (300 ft) contrasted with the vertical lines of the campanile and the transepts, is most impressive. It rests on a continuous and plain basement of granite, and only above the flat roofing of the chapels does the structure assume a varied outline.

Marble columns, with capitals of Byzantine type, support the galleries and other subsidiary parts of the building. The marble selected for the columns was, in some instances, obtained from formations quarried by the ancient Romans, chiefly in Greece.

High altar

editThe central feature of the decoration in the cathedral is the baldacchino over the high altar. This is one of the largest structures of its kind, the total width being 9.5 metres (31 ft), and the height 11.5 metres (38 ft). The upper part of white marble is richly inlaid with coloured marbles, lapis lazuli, pearl, and gold. Eight columns of yellow marble, from Verona, support the baldacchino over the high altar, and others, white and pink, from Norway, support the organ galleries.

Behind the baldacchino the crypt emerges above the floor of the sanctuary, and the podium thus formed is broken in the middle by the steps that lead up to the retro-choir. The curved wall of the crypt is lined with narrow slabs of green carystran marble. Opening out of this crypt is a smaller chamber, directly under the high altar. Here are laid the remains of the first two Archbishops of Westminster, Cardinal Wiseman and Cardinal Manning. The altar and relics of Saint Edmund of Canterbury occupy a recess on the south side of the chamber. The little chapel of Saint Thomas of Canterbury, entered from the north transept, is used as a chantry for Cardinal Vaughan. A large Byzantine style crucifix, suspended from the sanctuary arch, dominates the nave.

Chapels

editThe chapel of the Blessed Sacrament, on the north side of the sanctuary, and the Lady Chapel on the south, are entered from the transepts; they are 6.7 m (22 ft) wide, lofty, with open arcades, barrel vaulting, and apsidal ends. Over the altar of the Blessed Sacrament chapel a small baldacchino is suspended from the vault, and the chapel is enclosed with bronze grilles and gates through which people may enter. In the Lady Chapel the walls are clad in marble and the altar reredos is a mosaic of the Virgin and Child, surrounded by a white marble frame. The conches of the chapel contain predominantly blue mosaics of the Old Testament prophets Daniel, Isaiah, Jeremiah and Ezekiel. Unlike the Blessed Sacrament chapel, the chapel dedicated to the Blessed Mother is completely open. The building of the Lady Chapel was funded by Baroness Weld in memory of her second husband.[16]

Those chapels which may be entered from the aisles of the nave are also 6.7 metres (22 ft) wide, and roofed with simple barrel vaulting. The chapel of Saints Gregory and Augustine, next to the baptistery, from which it is separated by an open screen of marble, was the first to have its decoration completed. The marble lining of the piers rises to the springing level of the vaulting and this level has determined the height of the altar reredos, and of the screen opposite. On the side wall, under the windows, the marble dado rises to but little more than half this height. From the cornices the mosaic decoration begins on the walls and vault. This general arrangement applies to all the chapels yet each has its own distinct artistic character. Thus, in sharp contrast to the chapel dedicated to St. Gregory and St. Augustine which contains vibrant mosaics, the chapel of the Holy Souls employs a more subdued, almost funereal style, decoration with late Victorian on a background of silver.[17]

As in many Catholic churches, there are the Stations of the Cross to be found along the outer aisles. The ones at Westminster Cathedral are by the sculptor Eric Gill, and are considered to be amongst the finest examples of his work.[2]

Mosaics

editWhen the cathedral's architect John Bentley died, there were no completed mosaics in the cathedral and Bentley left behind precious little in terms of sketches and designs. Consequently, the subject and styles of the mosaics were influenced by donors as well as designers, overseen by a cathedral committee established for this purpose. Indeed, Bentley's influence is, in reality, only seen in the chapel dedicated to the Holy Souls.[17] Due to the prevailing absence of any real designs by Bentley, there was no real agreement as to how the mosaics should look, and in one instance, works already installed (in the Sacred Heart shrine) were removed after the death of the artist, George Bridge.[17]

Mosaics installed during the period 1912–1916 were mostly done by devotees of the Arts and Crafts Movement. Those in the Lady Chapel were installed by the experienced mosaicist Gertrude Martin (who had worked with George Bridge), in 1912–1913. The work was supervised by Anning Bell and Marshall, who later designed the mosaic of Christ enthroned which is above the entrance to the cathedral. The Tympanum of the portal shows in a Byzantine mosaic technique from left to right the kneeling St Peter with the Keys of Heaven, the Virgin Mary, Jesus Christ as Pantocrator on the throne, St Joseph, the Nursing Father of Jesus with a lily in his right hand, and in a kneeling position the canonized English King Edward the Confessor in royal regalia. As Jesus Christ blesses the viewer with his right hand, he holds in his left hand the Book of Life. The Latin inscription of the opened book pages reads: Ego sum ostium per me si quis introierit salvabitur (I am the gate; whoever enters through me will be saved; Gospel of John 10,9).

The mosaics in the chapel dedicated to Saint Andrew, paid for by The 4th Marquess of Bute, also belong to work of the Arts and Craft Movement.[18]

The five-year period 1930 to 1935 saw a tremendous amount of work done, with mosaics placed in the Lady Chapel, in the alcoves above the confessionals, in the crypt dedicated to Saint Peter, and on the sanctuary arch.

No new mosaics were installed until 1950 when one depicting St Thérèse of Lisieux (later replaced by a bronze) was placed in the south transept and another, in 1952, in memory of those in the Royal Army Medical Corps who died in World War II, in the chapel of Saint George. From 1960 to 1962, the Blessed Sacrament Chapel was decorated in a traditional, early Christian style, with the mosaics being predominantly pale pink in order to afford a sense of light and space. The designer, Boris Anrep, chose various Eucharistic themes such as the sacrifice of Abel, the hospitality of Abraham and the gathering of the manna in the wilderness, as well as the Feeding the multitude and the Wedding Feast at Cana. In his old age, Anrep also acted as adviser and principal sketch artist for the mosaics installed in the chapel of Saint Paul (1964–1965).[19] These mosaics depict various moments in the life of Paul; his occupation as a tent-maker, his conversion to Christ, the shipwreck on Malta and his eventual execution in Rome.

It was not until the visit of Pope John Paul II in 1982 that the next mosaic was installed above the north-west entrance. Rather than a scene, this mosaic is an inscription: Porta sis ostium pacificum per eum qui se ostium appellavit, Jesus Christum (May this door be the gate of peace through Him who called Himself the gate, Jesus Christ). In 1999, the mosaic of Saint Patrick, holding a shamrock and a pastoral staff as well as trampling on a snake, was installed at the entrance to the chapel in his honour. In 2001, a striking mosaic of Saint Alban, strongly influenced by the style of early Byzantine iconography, was installed by the designer, Christopher Hobbs. Due to the very favourable reception of the work, Hobbs was commissioned for further mosaics: the chapel to Saint Joseph which contains mosaics of the Holy Family (2003) and men working on Westminster Cathedral (2006). Hobbs also did the chapel in honour of Saint Thomas Becket illustrating the saint standing in front of the old Canterbury Cathedral on the chapel's east wall and the murder of Thomas on the west wall. The vault is decorated with a design of flowers, tendrils and roundels (2006). As of 2011[update], there were plans for further mosaics, including depictions of Saint Francis of Assisi and Saint Anthony in the narthex.[20]

Music

editDespite its relatively short history compared to other English cathedrals, Westminster has a distinguished choral tradition. It has its origin in the shared vision of Cardinal Vaughan, the cathedral's founder, and Sir Richard Runciman Terry, its inaugural Master of Music. Terry prepared his choristers for a year before their first sung service in public. For the remainder of his tenure (until 1924) he pursued a celebrated revival of great quantities of Latin repertoire from the English Renaissance, most of which had lain unsung ever since the Reformation. Students at the Royal College of Music who would become household names were introduced to their heritage when Charles Villiers Stanford sent them to the cathedral to hear "polyphony for a penny" (the bus fare). This programme also required honing the boys' sight-reading ability to a then-unprecedented standard.

The choir has commissioned many works from distinguished composers, many of whom are better known for their contribution to Anglican music, such as Benjamin Britten and Ralph Vaughan Williams. However, the choir is particularly renowned for its performance of Gregorian chant and polyphony of the Renaissance.

Unlike most other English cathedrals, Westminster does not have a separate quire; instead, the choir are hidden from view in the apse behind the high altar. This, with the excellent acoustic of the cathedral building, contributes to its distinctive sound.

Located in the west gallery, the Grand Organ of four manuals and 81 stops occupies a more commanding position than many British cathedral organs enjoy. Built by Henry Willis III from 1922 to 1932, it remains one of the most successful and admired. One of Louis Vierne's best-known organ pieces, "Carillon de Westminster", the final movement from Suite no. 3 (op. 54) of Pièces de Fantaisie, was originally improvised on it in 1924,[21] and the subsequent 1927 published version is dedicated to Willis.

The apse organ of fifteen stops was built in 1910 by Lewis & Co.[22] Although the Grand Organ has its own attached console, a console in the apse can play both instruments.

On 3 May 1902, some 3,000 people attended a concert of sacred music in the cathedral, organised to raise money for the Choir School and to test the acoustics in the building. The music was provided by an orchestra of a hundred and a choir of two hundred, including the Cathedral Choir, directed by Richard Terry. The programme included music by Wagner, Purcell, Beethoven, Palestrina, Byrd and Tallis. The acoustics proved to be excellent.[23] One year later, on 6 June 1903, the first performance in London of The Dream of Gerontius, a poem by Cardinal John Henry Newman, set to music by Edward Elgar, took place in the cathedral. The composer himself conducted, with Richard Terry at the organ.[24] Once again, the proceeds went to support the Cathedral Choir School.

John Tavener's The Beautiful Names, a setting of the 99 names of Allah found in the Qur'an, premièred in the cathedral on 19 June 2007, in a performance by the BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus in the presence of Charles, Prince of Wales.[25]

Choir

editThe founder of Westminster Cathedral, Cardinal Herbert Vaughan laid great emphasis on the beauty and integrity of the cathedral's liturgy. Initially, he determined there should be a community of Benedictine monks at the new cathedral, performing the liturgies and singing the daily Office. This caused great resentment amongst the secular clergy of the diocese, who felt they were being snubbed. In the end, negotiations with both the English Benedictines and the community of French Benedictines at Farnborough failed and a traditional choir of men and boys was set up instead.[26] Despite great financial problems, the Choir School opened on 5 October 1901 with eleven boy choristers, in the building originally intended for the monks. Cardinal Vaughan received the boys with the words "You are the foundation stones".[27] The Cathedral Choir was officially instituted three months later in January 1902.[28] Sung Masses and Offices were immediately established when the cathedral opened for worship in 1903, and have continued without interruption ever since.

In September 2020, Cardinal Vincent Nichols responded to a strategic review of sacred music at Westminster Cathedral, asking that "all those who profess to be fervent supporters of this precious inheritance of sacred music to become regular contributors to its financial support. It is, unquestionably, time to look ahead in order to ensure that this tradition of sacred music in Westminster Cathedral...can be put onto a firm footing for years to come."[29]

When the question of a musical director was first considered, the choice fell on the singer Sir Charles Santley, who had conducted the choir of the pro-cathedral in Kensington on several occasions. But Santley knew his limitations and refused.[30] Richard Runciman Terry—Director of Music at Downside Abbey School—then became the first director of music of Westminster Cathedral. It proved to be an inspired choice. Terry was both a brilliant choir trainer and a pioneering scholar, one of the first musicologists to revive the great works of the English and other European Renaissance composers. Terry built Westminster Cathedral Choir's reputation on performances of music—by Byrd, Tallis, Taverner, Palestrina and Victoria, among others—that had not been heard since the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and Mass at the cathedral was soon attended by inquisitive musicians as well as the faithful. The performance of great Renaissance Masses and motets in their proper liturgical context remains the cornerstone of the choir's activity.

Terry resigned in 1924, and was succeeded by Canon Lancelot Long who had been one of the original eleven choristers in 1901.

At the beginning of the Second World War, the boys were at first evacuated to Uckfield in East Sussex, but eventually the choir school was closed altogether for the remainder of the war. The music at the cathedral was performed by a reduced body of professional men singers.[31] During this period, from 1941 to 1947, the Master of Music was William Hyde, who had been the sub-organist under Richard Terry.[32]

Hyde was succeeded by George Malcolm, who developed the continental sound of the choir and consolidated its musical reputation—in particular through the now legendary recording of Victoria's Tenebrae responsories. More recent holders of the post have included Francis Cameron, Colin Mawby, Stephen Cleobury, David Hill, James O'Donnell and Martin Baker. In May 2021, Simon Johnson was appointed as the Master of Music.[33]

In addition to its performances of Renaissance masterpieces, Westminster Cathedral Choir has given many first performances of music written especially for it by contemporary composers. Terry gave the premières of music by Vaughan Williams (whose Mass in G minor received its liturgical performance at a Mass in the cathedral), Gustav Holst, Herbert Howells and Charles Wood; in 1959 Benjamin Britten wrote his Missa brevis for the choristers; and since 1960 works by Lennox Berkeley, William Mathias, Colin Mawby and Francis Grier have been added to the repertoire. Most recently four new Masses—by Roxanna Panufnik, James MacMillan, Sir Peter Maxwell Davies and Judith Bingham—have received their first performance in the cathedral. In June 2005 the choristers performed the world première of Sir John Tavener's Missa Brevis for boys' voices.

Westminster Cathedral Choir made its first recording in 1907. Many more have followed in the Westminster Cathedral Choir discography, most recently the series on the Hyperion label, and many awards have been conferred on the choir's recordings. Of these the most prestigious are the 1998 Gramophone Awards for both Best Choral Recording of the Year and Record of the Year, for the performance of Martin's Mass for Double Choir and Pizzetti's Requiem, conducted by O'Donnell. It is the only cathedral choir to have won in either of these categories.

When its duties at the cathedral permit, the choir also gives concert performances both at home and abroad. It has appeared at many important festivals, including Aldeburgh, Cheltenham, Salzburg, Copenhagen, Bremen and Spitalfields. It has appeared in many of the major concert halls of Britain, including the Royal Festival Hall, the Wigmore Hall and the Royal Albert Hall. The cathedral choir also broadcasts frequently on radio and television.

Westminster Cathedral Choir has undertaken a number of international tours, including visits to Hungary, Germany and the US. The choristers participated in the 2003 and 2006 International Gregorian chant Festival in Watou, Belgium, and the full choir performed twice at the Oslo International Church Music Festival in March 2006. In April 2005, 2007 and 2008 they performed as part of the "Due Organi in Concerto" festival in Milan. In October 2011, they sang the inaugural concert of the Institute for Sacred Music at Saint John's in Minnesota.

The cathedral is frequently referred to as the 'Drome'. This dates from the early 20th century days when the Lay Clerks were represented by Equity—the trade union for actors and variety artists. In the profession, it was jokingly referred to as 'The Westminster Hippodrome'—a nickname which was later shortened to the 'Drome'.[34]

Oremus magazine

editWestminster Cathedral has published a monthly magazine since 1896, before the building work was completed. The latest in a series of titles is Oremus, which first appeared in 1996. (The Latin word oremus translates into English as "Let us pray".) Oremus is a 32-page colour magazine, which contains features and articles by well-known members of the Catholic community, as well as non-Catholic commentators and leading figures within British society. It is the successor of titles such as the Westminster Cathedral Record, selling at 6d per copy from January 1896, the Westminster Cathedral Chronicle, a monthly, available from January 1907 at 2d a copy or 3/- a year, post paid, and the Westminster Cathedral Bulletin, first published in 1974. Dylan Parry, who edited the magazine between 2012 and August 2016, took the decision to make Oremus a free publication in 2013. The magazine is also available to download via Westminster Cathedral's website.[35][36]

Burials

editIn order of years of office:

- Richard Challoner (1691–1781) Vicar Apostolic of the London District (Re-interred in the cathedral 1946)

- Nicholas Wiseman (28 September 1850 – 15 February 1865) First Archbishop of Westminster upon the re-establishment of the Catholic hierarchy in England and Wales in 1850. (Re-interred in the cathedral 1907)

- Henry Edward Manning (16 May 1865 – 14 January 1892) Archbishop of Westminster. (Re-interred in the cathedral 1907)

- Herbert Vaughan (8 April 1832 – 19 June 1903) Archbishop of Westminster. (Re-interred in the cathedral 2005)

- Arthur Hinsley (1 April 1935 – 17 March 1943) Archbishop of Westminster

- Bernard Griffin (18 December 1943 – 19 August 1956) Archbishop of Westminster

- William Godfrey (3 December 1956 – 22 January 1963) Archbishop of Westminster

- John Heenan (22 February 1965 – 7 November 1975) Archbishop of Westminster

- Basil Hume (9 February 1976 – 17 June 1999) Archbishop of Westminster

- Cormac Murphy-O'Connor (15 February 2000 – 3 April 2009) (Died on 1 September 2017) Archbishop of Westminster and first emeritus Archbishop, since the other holders died in office

Also buried in the crypt is Alexander count Benckendorff, the Russian ambassador to the Court of St James's from 1903 until his death in 1917.

In popular culture

edit- In Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson's apocalyptic science fiction novel Lord of the World, Westminster Cathedral is the only church in London still used for religious purposes. The others have all been confiscated by the state.

- The Campanile Bell Tower of Westminster Cathedral was featured prominently in the Alfred Hitchcock film Foreign Correspondent, at which the attempted murder of a journalist played by Joel McCrea took place.

- In Shekhar Kapur's Elizabeth: The Golden Age scenes taking place at El Escorial were shot in Westminster Cathedral.

- The cathedral has been painted by London-born Irish artist Brian Whelan.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Historic England. "Wesminster Cathedral (1066500)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ a b "Westminster Cathedral – London, England". www.sacred-destinations.com. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ Mark Daly (16 October 2018). London Uncovered (New Edition): More than Sixty Unusual Places to Explore. White Lion Publishing. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-7112-3998-2.

- ^ Lance Day; Ian McNeil (11 September 2002). Biographical Dictionary of the History of Technology. Routledge. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-134-65019-4.

- ^ Betjeman, John (25 July 1974). A Pictorial History of English Architecture. Penguin Books Ltd. p. 95. ISBN 978-0140038248.

- ^ Westminster Cathedral Piazza Archived 19 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine from London Gardens Online retrieved 16 May 2013

- ^ "The New Roman Catholic Cathedral, Westminster". The Illustrated London News: 3. 20 July 1895 – via Archive.Org.

- ^ "The New Roman Catholic Cathedral, Westminster". The Illustrated London News: 3. 20 July 1895 – via Archive.org.

- ^ Howse, Christopher (30 April 2005). "Sacred Mysteries". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ^ Alba, M.J. (14 May 2013). "10 Most Famous Unfinished Buildings". Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ^ a b "Dedication of the Cathedral – Westminster Cathedral". www.westminstercathedral.org.uk. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ "Ex-Anglican bishops ordained as Catholics". BBC News. 15 January 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ^ "The Reinvention of the Catholic Church". The Atlantic. 11 December 2022.

- ^ Winefride de L'Hôpital, Westminster Cathedral and its Architect, vol. 1, p. 47.

- ^ "Data" (PDF). britishbricksoc.co.uk. 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ Cooksey, Pamela (4 October 2007). "Weld, Jane Charlotte [known as Baroness Weld] (1806–1871), convert to Roman Catholicism and benefactor". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/95696. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. Retrieved 14 May 2023. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b c Rogers, Patrick (July 2004). "Cathedral Mosaics: Part I – Trial and Error". Oremus. Westminster Cathedral. Archived from the original on 30 May 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ Rogers, Patrick (July 2004). "Cathedral Mosaics: Part III – The Arts and Crafts Men". Oremus. Westminster Cathedral. Archived from the original on 30 May 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ Rogers, Patrick (July 2004). "Cathedral Mosaics: Part V – A Russian Perspective". Oremus. Westminster Cathedral. Archived from the original on 30 May 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ Rogers, Patrick (July 2004). "Cathedral Mosaics: Part VI – The Journey proceeds". Oremus. Westminster Cathedral. Archived from the original on 30 May 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ "Westminster Cathedral - The Grand Organ". westminstercathedral.org.uk. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- ^ "Westminster Cathedral". Organrecitals.com. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ^ Patrick Rogers, Westminster Cathedral. An Illustrated History, London, 2012, p. 44.

- ^ ""Gerontius" At The Westminster Cathedral". Archived from the original on 22 September 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help), article in: The Tablet, 13 June 1903, p. 7. - ^ "Allah to be glorified in Westminster Cathedral". Catholic Action UK. 20 June 2007. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Westminster Cathedral 1895–1995. A souvenir brochure compiled by Mgr George Stack, Cathedral Administrator, p. 16.

- ^ Alan Mould, The English Chorister. A History, London, 2007, p. 221.

- ^ Patrick Rogers, Westminster Cathedral. An Illustrated History, London, 2012, p.38.

- ^ "Cardinal's Response to Strategic Review of Sacred Music". rcdow.org.uk. 25 September 2020. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ^ Rev. Lancelot Long, A "Song School" Jubilee. Article in The Tablet, 2 October 1926.

- ^ Peter Doyle, Westminster Cathedral 1895–1995, London, 1995, p. 64.

- ^ The Tablet, 6 February 1954, p. 18.

- ^ "Westminster Cathedral Appoints Simon Johnson as Master of Music -". Rhinegold. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ "Oremus, Nov. 2017" (PDF).

- ^ "Oremus – The Cathedral Magazine". Westminster Cathedral. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ^ "Behind the Scenes of Oremus". Westminster Cathedral. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

Sources

edit- This article incorporates text (concerning architecture) from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Westminster Cathedral". Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company.

- Winefride de L'Hôpital. Westminster Cathedral and Its Architect, 2 vols. Dodd, Mead & Co., New York (1919).

- Patrick Rogers. Westminster Cathedral: from Darkness to Light. Burns & Continuum International Publishing Group, London (2003). ISBN 0-86012-358-8.

- Peter Doyle. Westminster Cathedral: 1895–1995. Geoffrey Chapman Publishers, London (1995). ISBN 978-0-225-66684-7.

- John Browne and Timothy Dean. Westminster Cathedral: Building of Faith. Booth-Clibborn Editions, London (1995). ISBN 1-873968-45-0.

- John Jenkins and Alana Harris, 'More English than the English, more Roman than Rome? Historical signifiers and cultural memory at Westminster Cathedral', Religion 49:1 (2019), pp. 48–73 https://doi.org/10.1080/0048721X.2018.1515328