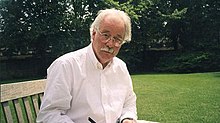

Winfried Georg Sebald[1] (18 May 1944 – 14 December 2001), known as W. G. Sebald or (as he preferred) Max Sebald, was a German writer and academic. At the time of his death at the age of 57, he was according to The New Yorker ”widely recognized for his extraordinary contribution to world literature.”[2]

W. G. Sebald | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Winfried Georg Sebald 18 May 1944 Wertach, Bavaria, Germany |

| Died | 14 December 2001 (aged 57) Norfolk, England |

| Occupation | Writer, academic |

| Language | German |

| Education | University of Freiburg University of Fribourg University of East Anglia (PhD) University of Hamburg |

| Notable works | Vertigo The Emigrants The Rings of Saturn Austerlitz |

Life

editSebald was born in Wertach, Bavaria, the second of the three children of Rosa and Georg Sebald, and his parents' only son. From 1948 to 1963, he lived in Sonthofen.[3] His father had joined the Reichswehr in 1929 and served in the Wehrmacht under the Nazis. His father remained a detached figure, a prisoner of war until 1947; his maternal grandfather, the small-town police officer Josef Egelhofer (1872–1956), was the most important male presence during his early years.[4] Sebald was shown images of The Holocaust while at school in Oberstdorf and recalled that no one knew how to explain what they had just seen. The Holocaust and European modernity, especially its modes of warfare and persecution, later became central themes in his work.[5]

Sebald studied German and English literature first at the University of Freiburg and then at the University of Fribourg in Switzerland, where he received a degree in 1965.[6] He was a Lector at the University of Manchester from 1966 to 1969. He returned to St. Gallen in Switzerland for a year hoping to work as a teacher but could not settle. Sebald married his Austrian-born wife, Ute, in 1967. In 1970 he became a lecturer at the University of East Anglia (UEA). There, he completed his PhD in 1973 with a dissertation entitled The Revival of Myth: A Study of Alfred Döblin's Novels.[7][8] Sebald acquired habilitation from the University of Hamburg in 1986.[9] In 1987, he was appointed to a chair of European literature at UEA. In 1989 he became the founding director of the British Centre for Literary Translation. He lived at Wymondham and Poringland while at UEA.

Final year

editThe 2001 publication of Austerlitz (both in German and English) secured Sebald worldwide fame:[10] "Austerlitz was received enthusiastically on an international scale; literary critics celebrated it frenetically; the book established Sebald as a modern classic."[11] He was tipped as a possible future winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature.[2][12][13] With grown and still growing reputation, he was now in high demand by literary institutions and radio programmes throughout Western Europe.[14] Newspapers, magazines and journals from Germany, Austria, Belgium, the Netherlands, Britain and the U.S. urged him for interviews.[15] "Condemned to unrest I am, I am afraid", he wrote to Andreas Dorschel in June 2001, returning from one trip and setting out for the next.

For a considerable time, Sebald had been aware of a congenital cardiac insufficiency;[16] to a visitor from the US, he described himself in August 2001 as "someone who knows he has to leave before too long".[17] Sebald died while driving near Norwich in December 2001.[18] The event threw the literary public into a state of shock.[19] Sebald had been driving with his daughter Anna, who survived the crash.[12] The coroner's report, released some six months after the accident, stated that Sebald had suffered a heart attack and had died of this condition before his car swerved across the road and collided with an oncoming lorry.[20]

W.G. Sebald is buried in St. Andrew's churchyard in Framingham Earl, close to where he lived.[21]

Themes and style

editSebald's works are largely concerned with the themes of memory and loss of memory (both personal and collective) and decay (of civilizations, traditions or physical objects). They are, in particular, attempts to reconcile himself with, and deal in literary terms with, the trauma of the Second World War and its effect on the German people. In On the Natural History of Destruction (1999), he wrote an essay on the wartime bombing of German cities and the absence in German writing of any real response. His concern with The Holocaust is expressed in several books delicately tracing his own biographical connections with Jews.[22] Contrary to Germany's political and intellectual establishment,[23] Sebald denied the singularity of the Holocaust: "I see the catastrophe caused by the Germans, dreadful as it was, by no means as a singular event – it developed with a certain logic from European history and then, for the same reason, ate itself into European history."[24] Consequently, Sebald, in his literary work, always tried to situate and contextualize the Holocaust within modern European history, even avoiding a focus on Germany.

Sebald completely rejected the mainstream of Western German literature of the 1950s to 1970s, as represented by Heinrich Böll and Günter Grass: "I hate [...] the German postwar novel like pestilence."[25] He took a deliberate counter-stance. Sebald's distinctive and innovative novels (which he mostly called simply: prose ("Prosa")[26]) were written in an intentionally somewhat old-fashioned and elaborate German (one passage in Austerlitz famously contains a sentence that is 9 pages long). Sebald closely supervised the English translations (principally by Anthea Bell and Michael Hulse). They include Vertigo, The Emigrants, The Rings of Saturn and Austerlitz. They are notable for their curious and wide-ranging mixture of fact (or apparent fact), recollection and fiction, often punctuated by indistinct black-and-white photographs set in evocative counterpoint to the narrative rather than illustrating it directly. His novels are presented as observations and recollections made while travelling around Europe. They also have a dry and mischievous sense of humour.[27]

Sebald was also the author of three books of poetry: For Years Now with Tess Jaray (2001), After Nature (1988), and Unrecounted (2004).

Works

edit- 1988 After Nature. London: Hamish Hamilton. (Nach der Natur. Ein Elementargedicht) English ed. 2002

- 1990 Vertigo. London: Harvill. (Schwindel. Gefühle) English ed. 1999

- 1992 The Emigrants. London: Harvill. (Die Ausgewanderten. Vier lange Erzählungen) English ed. 1996

- 1995 The Rings of Saturn. London: Harvill. (Die Ringe des Saturn. Eine englische Wallfahrt) English ed. 1998

- 1998 A Place in the Country. (Logis in einem Landhaus) English ed. 2013

- 1999 On the Natural History of Destruction. London: Hamish Hamilton. (Luftkrieg und Literatur: Mit einem Essay zu Alfred Andersch) English ed. 2003

- 2001 Austerlitz. London: Hamish Hamilton. English translation by Anthea Bell won the 2002 Independent Foreign Fiction Prize.

- 2001 For Years Now. London: Short Books.

- 2003 Unrecounted London: Hamish Hamilton. (Unerzählt, 33 Texte) English ed. 2004

- 2003 Campo Santo London: Hamish Hamilton. (Campo Santo, Prosa, Essays) English ed. 2005

- 2008 Across the Land and the Water: Selected Poems, 1964–2001. (Über das Land und das Wasser. Ausgewählte Gedichte 1964–2001.) English ed. 2012

Influences

editThe works of Jorge Luis Borges, especially "The Garden of Forking Paths" and "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius", were a major influence on Sebald. (Tlön and Uqbar appear in The Rings of Saturn.)[28] In a conversation during his final year, Sebald named Gottfried Keller, Adalbert Stifter, Heinrich von Kleist and Jean Paul as his literary models.[29] He also credited the Austrian novelist Thomas Bernhard as a major influence on his work,[30] and paid homage within his work to Kafka[31] and Nabokov (the figure of Nabokov appears in every one of the four sections of The Emigrants).[32]

Memorials

editSebaldweg ("Sebald Way")

editAs a memorial to the writer, in 2005 the town of Wertach created an eleven kilometre long walkway called the "Sebaldweg". It runs from the border post at Oberjoch (1,159m) to W. G. Sebald's birthplace on Grüntenseestrasse 3 in Wertach (915m). The route is that taken by the narrator in Il ritorno in patria, the final section of Vertigo ("Schwindel. Gefühle") by W. G. Sebald. Six steles have been erected along the way with texts from the book relating to the respective topographical place, and also with reference to fire and to people who died in the Second World War, two of Sebald's main themes.[33]

Sebald Copse

editIn the grounds of the University of East Anglia in Norwich a round wooden bench encircles a copper beech tree, planted in 2003 by the family of W. G. Sebald in memory of the writer. Together with other trees donated by former students of the writer, the area is called the "Sebald Copse". The bench, whose form echoes The Rings of Saturn, carries an inscription from the penultimate poem of Unerzählt ("Unrecounted"): "Unerzählt bleibt die Geschichte der abgewandten Gesichter" ("Unrecounted always it will remain the story of the averted faces"[34])

Patience (After Sebald)

editIn 2011, Grant Gee made the documentary Patience (After Sebald) about the author's trek through the East Anglian landscape.[35]

References

editCitations

edit- ^ In a number of interviews, Sebald claimed that his third given name was "Maximilian" – this has, however, turned out not to be the case; see Uwe Schütte, W.G. Sebald. Leben und literarisches Werk. Berlin/Boston, MA: de Gruyter, 2020, p. 8.

- ^ a b O'Connell, Mark (14 December 2011). "Why You Should Read W. G. Sebald". The New Yorker.

- ^ W.G. Sebald, Schriftsteller und Schüler am Gymnasium Oberstdorf Archived 3 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine (in German)

- ^ Thomas Diecks (2010). "Sebald, W. G. (Max, eigentlich Winfried Georg Maximilian)". Neue Deutsche Biographie. Historische Kommission bei der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (HiKo), München. pp. 106–107. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ Carrigan Jr., Henry L. (2010). W. G. Sebald (4th ed.). Critical Survey of Long Fiction.

- ^ Eric Homberger, "WG Sebald," The Guardian, 17 December 2001, accessed 9 October 2010.

- ^ Martin, James R. (2013). "On Misunderstanding W.G. Sebald" (PDF). Cambridge Literary Review. IV (7): 123–38. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ Sebald, W. G. (1973). The Revival of myth: a study of Alfred Döblin's novels. British Library EThOS (Ph.D). Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ [1][permanent dead link]

- ^ Uwe Schütte, 'Rezeption | Anglo-amerikanischer Raum'. In: Claudia Öhlschläger, Michael Niehaus (eds.), W.G. Sebald-Handbuch: Leben – Werk – Wirkung. Stuttgart: Metzler, 2017, pp. 305–309, pp. 305 and 306.

- ^ Christian Hein, 'Rezeption | Deutschsprachiger Raum'. In: Claudia Öhlschläger, Michael Niehaus (eds.), W.G. Sebald-Handbuch: Leben – Werk – Wirkung. Stuttgart: Metzler, 2017, pp. 300–305, p. 300: "Austerlitz wurde international begeistert rezipiert, von der Literaturkritik frenetisch gefeiert und verlieh Sebald den Status eines modernen Klassikers."

- ^ a b Gussow, Mel (15 December 2001). "W. G. Sebald, Elegiac German Novelist, Is Dead at 57". The New York Times.

- ^ In 2007 Horace Engdahl, former secretary of the Swedish Academy, mentioned Sebald, Ryszard Kapuściński and Jacques Derrida as three recently deceased writers who would have been worthy laureates. "Tidningen Vi – STÃNDIGT DENNA HORACE!". Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ Philippa Comber, 'Autorbiographie'. In: Claudia Öhlschläger, Michael Niehaus (eds.), W.G. Sebald-Handbuch: Leben – Werk – Wirkung. Stuttgart: Metzler, 2017, pp. 5–9, p. 9.

- ^ Uwe Schütte, W.G. Sebald. Einführung in Leben und Werk. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2011, p. 33.

- ^ Uwe Schütte, Figurationen. Zum lyrischen Werk von W.G. Sebald. Eggingen: Isele, 2021, p. 49.

- ^ Lynne Sharon Schwartz (ed.), The Emergence of Memory: Conversations with W.G. Sebald, New York, NY/London/Melbourne/Toronto 2007, p. 162.

- ^ Vanessa Thorpe, 'Cult novelist killed in car accident', The Observer, 16 December 2001.

- ^ Scott Denham, 'Forword: The Sebald Phenomenon', in: Scott Denham, Mark McCulloh (eds.), W.G. Sebald: History – Memory – Trauma, Berlin/New York, NY: de Gruyter 2006, pp. 1–6, p. 2: ”Sebald's premature death in December, 2001, shocked the literary world in Germany as well as in his home, Britain, and in the U.S.”

- ^ Angier, Carole (2021). Speak, Silence: In Search of W.G. Sebald. Bloomsbury.

- ^ Uwe Schütte, W.G. Sebald: Einführung in Leben und Werk. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2011, p. 33.

- ^ Cf. Carol Jacobs, Sebald's Vision. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2015, p. 72 and passim.

- ^ as represented, e.g., by Richard von Weizsäcker and Jürgen Habermas.

- ^ W.G. Sebald, "Auf ungeheuer dünnem Eis." Gespräche 1971 bis 2001, ed. Torsten Hoffmann, Frankfurt/M.: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 2011, p. 260: "Ich sehe die von den Deutschen angerichtete Katastrophe, grauenvoll wie sie war, durchaus nicht als Unikum an – sie hat sich mit einer gewissen Folgerichtigkeit herausentwickelt aus der europäischen Geschichte und sich dann, aus diesem Grunde auch, hineingefressen in die europäische Geschichte."

- ^ W.G. Sebald, "Auf ungeheuer dünnem Eis." Gespräche 1971 bis 2001, ed. Torsten Hoffmann, Frankfurt/M.: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 2011, p. 77: "Ich hasse [...] den deutschen Nachkriegsroman wie die Pest." Ironically, Sebald received the Heinrich-Böll-Preis in 1997.

- ^ Peter Morgan distinguishes the "novel" Austerlitz from the "prose narratives" Vertigo, The Emigrants and The Rings of Saturn ('The Sign of Saturn: Melancholy, Homelessness and Apocalypse in W.G. Sebald's Prose Narratives.' In: Franz-Josef Deiters (ed.), Passagen: 50 Jahre Germanistik an der Monash Universität. St. Ingbert: Röhrig, 2010, pp. 491–517, p. 491).

- ^ Wood, James (29 May 2017). "W.G. Sebald, Humorist". The New Yorker. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ McCulloh, Mark Richard (2003). Understanding W. G. Sebald. University of South Carolina Press. p. 66. ISBN 1-57003-506-7. Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- ^ Lynne Sharon Schwartz (ed.), The Emergence of Memory: Conversations with W.G. Sebald, New York, NY/London/Melbourne/Toronto 2007, p. 166.

- ^ "Sebald's Voice", 17 April 2007

- ^ "Among Kafka's Sons: Sebald, Roth, Coetzee", 22 January 2013; review of Three Sons by Daniel L. Medin, ISBN 978-0810125681

- ^ "Netting the Butterfly Man: The Significance of Vladimir Nabokov in W. G. Sebald's The Emigrants" by Adrian Curtin and Maxim D. Shrayer, in Religion and the Arts, vol. 9, nos. 3–4, pp. 258–283, 1 November 2005

- ^ Gutbrod, Hans (31 May 2023). "Sebald's Path in Wertach -- Commemorating the Commemorator". Cultures of History Forum. doi:10.25626/0146 (inactive 1 November 2024). Retrieved 6 June 2023.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Jo Catling; Richard Hibbitt, eds. (2011). Saturn's Moons, W. G. Sebald - A Handbook. Translated by Hamburger, Michael. Legenda. p. 659. ISBN 978-1-906540-0-29.

- ^ "Patience (After Sebald): watch the trailer – video", The Guardian (31 January 2012)

General and cited sources

edit- Arnold, Heinz Ludwig (ed.). W. G. Sebald. Munich, 2003 (Text+Kritik. Zeitschrift für Literatur. IV, 158). Includes bibliography.

- Bewes, Timothy. "What is a Literary Landscape? Immanence and the Ethics of Form". differences, vol. 16, no. 1 (Spring 2005), 63–102. Discusses the relation to landscape in the work of Sebald and Flannery O'Connor.

- Bigsby, Christopher. Remembering and Imagining the Holocaust: The Chain of Memory. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Blackler, Deane. Reading W. G. Sebald: Adventure and Disobedience. Camden House, 2007.

- Breuer, Theo, "Einer der Besten. W. G. Sebald (1944–2001)" in T.B., Kiesel & Kastanie. Von neuen Gedichten und Geschichten, Edition YE 2008.

- Denham, Scott and Mark McCulloh (eds.). W. G. Sebald: History, Memory, Trauma. Berlin, Walter de Gruyter, 2005.

- Grumley, John, "Dialogue with the Dead: Sebald, Creatureliness, and the Philosophy of Mere Life", The European Legacy, 16,4 (2011), 505–518.

- Jacobs, Carol. Sebald's Vision. New York: Columbia University Press, 2017.

- Long, J. J. W. G. Sebald: Image, Archive, Modernity. New York, Columbia University Press, 2008.

- Long, J. J. and Anne Whitehead (eds.). W. G. Sebald: A Critical Companion. Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2006.

- McCulloh, Mark R. Understanding W. G. Sebald. University of South Carolina Press, 2003.

- Patt, Lise et al. (eds.). Searching for Sebald: Photography after W. G. Sebald. ICI Press, 2007. An anthology of essays on Sebald's use of images, with artist's projects inspired by Sebald.

- Wylie, John. "The Spectral Geographies of W. G. Sebald". Cultural Geographies, 14,2 (2007), 171–188.

- Zaslove, Jerry. "W. G. Sebald and Exilic Memory: His Photographic Images of the Cosmogony of Exile and Restitution". Journal of the Interdisciplinary Crossroads, Vol. 3 (No. 1) (April 2006).

- Rupprecht, Caroline. “Silkworms and Concentration Camps: W.G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn and Austerlitz” Asian Fusion: New Encounters in the Asian-German Avant-garde, Peter Lang, 2020. 33-54.

External links

edit| External image | |

|---|---|

| Max Sebald |

- Complete bibliography of Sebald's works

- An essay by Ben Lerner on Sebald in The New York Review of Books

- Jaggi, Maya (20 December 2001). "The last word". The Guardian. The last interview

- Mitchelmore, Stephen (1 November 2004). "W. G. Sebald: Looking and Looking Away". Spike Magazine.

- Audio interview with Sebald on KCRW's Bookworm

- Sebald-Forum

- BBC Radio4 Program: "A German Genius in Britain"