A vocal register is a range of tones in the human voice produced by a particular vibratory pattern of the vocal folds. These registers include modal voice (or normal voice), vocal fry, falsetto, and the whistle register.[1][2][3] Registers originate in laryngeal function. They occur because the vocal folds are capable of producing several different vibratory patterns. Each of these vibratory patterns appears within a particular range of pitches and produces certain characteristic sounds.[1][3][4]

In speech pathology, the vocal register has three components: a certain vibratory pattern of the vocal folds, a certain series of pitches, and a certain type of sound. Although this view is also adopted by many vocal pedagogists, others define vocal registration more loosely than in the sciences, using the term to denote various theories of how the human voice changes, both subjectively and objectively, as it moves through its pitch range.[2] There are many divergent theories on vocal registers within vocal pedagogy, making the term somewhat confusing and at times controversial within the field of singing. Vocal pedagogists may use the term vocal register to refer to any of the following:[2]

- a particular part of the vocal range such as the upper, middle, or lower registers

- a resonance area such as chest voice or head voice

- a phonatory process

- a certain vocal timbre

- a region of the voice defined or delimited by vocal breaks

Manuel Garcia II in the late nineteenth century was one of the first to develop a scientific definition of registers, a definition that is still used by pedagogues and vocal teachers today.

- "A register is a series of homogeneous sounds produced by one mechanism, differing essentially from another series of equally homogeneous sounds produced by another mechanism."[5]

Another definition is from Clifton Ware in the 1990s.

- "A series of distinct, consecutive, homogeneous vocal tones that can be maintained in pitch and loudness throughout a certain range."[6]

A register consists of the homogeneous tone qualities produced by the same mechanical system, whereas registration is the process of using and combining the registers to achieve artistic singing. For example: a skilled singer moves through their range and dynamics smoothly, so that you are unaware of register changes. This process could be described as good or clean registration.[7] The term "register" originated in the sixteenth century. Before then, it was recognized that there were different "voices". As teachers started to notice how different the ranges on either side of the passaggi or breaks in the voice were, they were compared to different sets of pipes in an organ. These clusters of pipes were called registers, so the same term was adopted for voices.[8]

Vibratory patterns

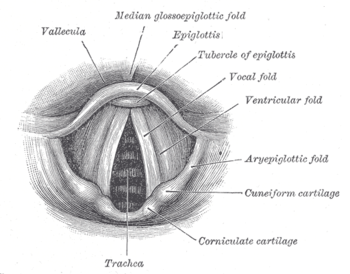

editVocal registers arise from different vibratory patterns produced by the vocal cords. Research by speech pathologists and some vocal pedagogists has revealed that the vocal cords are capable of producing at least four distinct vibratory forms, although not all persons can produce all of them. The first of these vibratory forms is known as natural or normal voice;[9] another name for it is modal voice, which is widely used in both speech pathology and vocal pedagogy publications. In this usage, modal refers to the natural disposition or manner of action of the vocal cords. The other three vibratory forms are known as vocal fry, falsetto, and whistle. Each of these four registers has its own vibratory pattern, its own pitch range (although there is some overlap), and its own characteristic sound. Arranged by the pitch ranges covered, vocal fry is the lowest register, modal voice is next, then falsetto, and finally the whistle register.[4][9]

While speech pathologists and scholars of phonetics recognize four registers, vocal pedagogists are divided. Indiscriminate use of the word register has led to confusion and controversy about the number of registers in the human voice within vocal pedagogical circles. This controversy does not exist within speech pathology and the other sciences, because vocal registers are viewed from a purely physiological standpoint concerned with laryngeal function. Writers concerned with the art of singing state that there are anywhere from one to seven registers present. The diversity of opinion is wide with no consensus.[9]

The prevailing practice within vocal pedagogy is to divide both men and women's voices into three registers. Men's voices are designated "chest", "head", and "falsetto" and women's voices are "chest", "middle", and "head". This way of classifying registers, however, is not universally accepted. Many vocal pedagogists blame this confusion on the incorrect use of the terms "chest register" and "head register". These professionals argue that, since all registers originate in laryngeal function, it is meaningless to speak of registers being produced in the chest or head. The vibratory sensations which are felt in these areas are resonance phenomena and should be described in terms related to resonance, not to registers. These vocal pedagogists prefer the terms "chest voice" and "head voice" over the term register. Many of the problems described as register problems are actually problems of resonance adjustment. This helps to explain the multiplicity of registers which some vocal pedagogists advocate.[2] For more information on resonance, see Vocal resonation.

Various types of chest or head noises can be made in different registers of the voice. This happens through differing vibratory patterns of the vocal folds and manipulation of the laryngeal muscles.[10] "Chest voice" and "head voice" can be considered the simplest registers to differentiate between. However, there are other sounds other than pure chest voice and head voice that a voice can make. These sounds or timbres exist on a continuum that is more complex than singing purely in chest voice and head voice. The vocal timbres created by physical changes in the vocal fold vibrations and muscular changes in the laryngeal muscles are known as glottal configurations.[11] These configurations happen as a result of adduction and abduction of the glottis. A glottal configuration is the area in which the vocal folds come together when phonating. Glottal configurations existing on this continuum are adducted chest, abducted chest, adducted falsetto, and abducted falsetto. In this case, falsetto could also be referred to as head voice as it applies to females as well. Vocally, the process of adduction is when the posterior of the glottis is closed. Abduction is when the posterior of the glottis is open. An example of adducted chest is belting as well as bass, baritone, and tenor classical singing. Abducted falsetto, on the opposite end of the spectrum, sounds very breathy and can possibly be a sign of a lack of vocal fold closure. However, in styles like jazz and pop, this breathy falsetto is a necessary singing technique for these genres. Abducted chest is a lower, breathier phonation occurring in the chest register, also occurring in jazz and pop styles. Abducted falsetto is treble classical singing. Chestmix and headmix lie on this continuum as well with chest mix being which is more adducted than headmix.[12]

These different vocal fold vibratory patterns occur as the result of certain laryngeal muscles being either active or inactive. During adducted and abducted chest voice, the thyroarytenoid muscle is always activated while during falsetto this muscle is not activated. When the posterior of the glottis is closed the interarytenoid muscle is engaged. This occurs in both adducted falsetto and adducted chest. [13]

The confusion which exists concerning the definition and number of registers is due in part to what takes place in the modal register when a person sings from the lowest pitches of that register to the highest pitches. The frequency of vibration of the vocal folds is determined by their length, tension, and mass. As pitch rises, the vocal folds are lengthened, tension increases, and their thickness decreases. In other words, all three of these factors are in a state of flux in the transition from the lowest to the highest tones.[1]

If a singer holds any of these factors constant and interferes with their progressive state of change, their laryngeal function tends to become static and eventually breaks occur, with obvious changes of tone quality. These breaks are often identified as register boundaries or as transition areas between registers. The distinct change or break between registers is called a passaggio or a ponticello.[14] Vocal pedagogists teach that, with study, a singer can move effortlessly from one register to another with ease and consistent tone. Registers can even overlap while singing. Teachers who prefer the theory of "blending registers" usually help students through the "passage" from one register to another by hiding their "lift" (where the voice changes).

However, many pedagogists disagree with this distinction of boundaries, blaming such breaks on vocal problems which have been created by a static laryngeal adjustment that does not permit the necessary changes to take place. This difference of opinion has affected the different views on vocal registration.[2]

Vocal fry register

editThe vocal fry register is the lowest vocal register and is produced through a loose glottal closure which will permit air to bubble through with a popping or rattling sound of a very low frequency. The chief use of vocal fry in singing is to obtain pitches of very low frequency which are not available in modal voice. This register may be used therapeutically to improve the lower part of the modal register. This register is not used often in singing, but male quartet pieces, and certain styles of folk music for both men and women have been known to do so.[2]

Modal voice register

editThe modal voice is the usual register for speaking and singing, and the vast majority of both are done in this register. As pitch rises in this register, the vocal folds are lengthened, tension increases, and their edges become thinner. A well-trained singer or speaker can phonate two octaves or more in the modal register with consistent production, beauty of tone, dynamic variety, and vocal freedom. This is possible only if the singer or speaker avoids static laryngeal adjustments and allows the progression from the bottom to the top of the register to be a carefully graduated continuum of readjustments.[9]

Falsetto register

editThe falsetto register lies above the modal voice register and overlaps the modal register by approximately one octave. The characteristic sound of falsetto is flute-like with few overtones present. The essential difference between the modal and falsetto registers lies in the amount and type of vocal cord involvement. The falsetto voice is produced by the vibration of the ligamentous edges of the vocal cords, in whole or in part, and the main body of the fold is more or less relaxed. In contrast, the modal voice involves the whole vocal cord with the glottis opening at the bottom first and then at the top. The falsetto voice is also more limited in dynamic variation and tone quality than the modal voice.[9]

Whistle register

editThe whistle register is the highest register of the human voice.[15] The whistle register is so called because the timbre of the notes that are produced from this register are similar to that of a whistle or the upper notes of a flute, whereas the modal register tends to have a warmer, less shrill timbre.

Passaggio

editThe Passaggio is a bridge or transition point between the different registers of the voice. Singers are often trained to navigate this area in the voice. Instabilities often happen in this bridge while the voice is phonating on pitches within this location. When a singer does not navigate this area sufficiently the voice folds temporarily lose the mucosal wave pattern resulting in an audible crack. These cracks can be navigated often through changing vowel. The female voice has two passaggios, primo and secondo passaggio.[16] The male voice has two passaggios as well, however the points of transition lie differently than those of a treble singer and are also navigated in a different manner.[17]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c Large, John (February–March 1972). "Towards an Integrated Physiologic-Acoustic Theory of Vocal Registers". The NATS Bulletin. 28: 30–35.

- ^ a b c d e f McKinney, James (1994). The Diagnosis and Correction of Vocal Faults. Genovex Music Group. ISBN 978-1-56593-940-0.

- ^ a b Appelman, D. Ralph (1986). The Science of Vocal Pedagogy: Theory and Application. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-20378-6.

- ^ a b Johnson, Alex; Barbara Jacobson; Carol Frattali; Robert Miller; Michael Benninger; J Brown; Carl Coelho; Kathleen Youse; Glendon Gardner; Lee Ann Golper; Jacqueline Hinckley; Michael Karnell; Susan Langmore; Jeri Logemann (2006). Medical Speech-Language Pathology. Thieme. ISBN 978-1-58890-320-4.

- ^ Garcia, Manuel. Hints on Singing. London: E. Ascherberg, 1894. Print.

- ^ Ware, Clifton. Basics of Vocal Pedagogy: The Foundations and Process of Singing. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1998. Print.

- ^ Ware, Clifton. Basics of Vocal Pedagogy: The Foundations and Process of Singing. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1998. Print.

- ^ Alderson, Richard. Complete Handbook of Voice Training. West Nyack, NY: Parker Pub., 1979. Print.

- ^ a b c d e Greene, Margaret; Lesley Mathieson (2001). The Voice and its Disorders. John Wiley & Sons; 6th Edition. ISBN 978-1-86156-196-1.

- ^ Herbst, Christian T.; Ternström, Sten; Švec, Jan G. (2009-02-05). "Investigation of four distinct glottal configurations in classical singing—A pilot study". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 125 (3): EL104–EL109. Bibcode:2009ASAJ..125L.104H. doi:10.1121/1.3057860. ISSN 0001-4966. PMID 19275279.

- ^ Herbst, Christian T.; Ternström, Sten; Švec, Jan G. (2009-02-05). "Investigation of four distinct glottal configurations in classical singing—A pilot study". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 125 (3): EL104–EL109. Bibcode:2009ASAJ..125L.104H. doi:10.1121/1.3057860. ISSN 0001-4966. PMID 19275279.

- ^ Kochis-Jennings, Karen Ann (2008). Intrinsic laryngeal muscle activity and vocal fold adduction patterns in female vocal registers (Thesis). The University of Iowa. doi:10.17077/etd.gvo1u70h.

- ^ Herbst, Christian T.; Ternström, Sten; Švec, Jan G. (2009-03-01). "Investigation of four distinct glottal configurations in classical singing—A pilot study". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 125 (3): EL104–EL109. doi:10.1121/1.3057860. ISSN 0001-4966. PMID 19275279.

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Opera. John Warrack and Ewan West, ISBN 0-19-869164-5

- ^ Vocalist.org.uk. "Voice Registers: Chest, head and other voices at Vocalist.org.uk". www.vocalist.org.uk. Retrieved 2017-09-26.

- ^ Echternach, Matthias; Burk, Fabian; Köberlein, Marie; Selamtzis, Andreas; Döllinger, Michael; Burdumy, Michael; Richter, Bernhard; Herbst, Christian Thomas (2017-05-03). Larson, Charles R. (ed.). "Laryngeal evidence for the first and second passaggio in professionally trained sopranos". PLOS ONE. 12 (5): e0175865. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1275865E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0175865. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5414960. PMID 28467509.

- ^ "Passaggio (i)", Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2001, doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.21026, retrieved 2024-02-23

Further reading

edit- Van den Berg, J.W. (December 1963). "Vocal Ligaments versus Registers". The NATS Bulletin. 19: 18.