The Villa Tunari Massacre was a 27 June 1988 mass murder committed by UMOPAR (Rural Patrol Mobile Unit) troops in response to a protest by coca-growing peasants (cocaleros) in the town of Villa Tunari in Chapare Province, Bolivia. The cocalero movement had mobilized since late May 1988 in opposition to coca eradication under Law 1008, then on the verge of becoming law.[1] According to video evidence and a joint church-labor investigative commission, UMOPAR opened fired on unarmed protesters, at least two of whom were fatally shot, and many of whom fled to their deaths over a steep drop into the San Mateo River. The police violence caused the deaths of 9 to 12 civilian protesters, including three whose bodies were never found, and injured over a hundred.[2][3][4] The killings were followed by further state violence in Villa Tunari, Sinahota, Ivirgarzama, and elsewhere in the region, including machine gun fire, beatings, and arrests.

| Villa Tunari massacre | |

|---|---|

| Part of Criminalization of coca in Bolivia | |

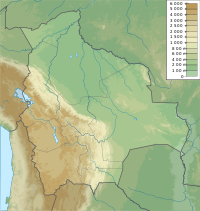

| Location | Villa Tunari, Chapare Province, Bolivia |

| Coordinates | 16°58′S 65°25′W / 16.967°S 65.417°W |

| Date | June 27, 1988 |

| Deaths | 9–12 Bolivian civilians |

| Perpetrators | Rural Mobile Patrol (UMOPAR) Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) (allegedly) |

| Motive | Repression of protest |

The massacre helped bring about the consolidation of Chapare coca growers' unions into the Coordinadora of the Six Federations of the Tropic of Cochabamba.[1]

Representatives of the National Congress, Catholic Church, Permanent Assembly for Human Rights, and the Central Obrera Boliviana labor federation formed a joint "multisectoral commission" to investigate the repression in the Chapare, which traveled to the region on 30 June 1988.[5]

Background

editUMOPAR, a police unit with military training,[6] was created in 1983 for the purpose of overseeing coca eradication in Bolivia. They received tactical and technical support from the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) who maintained an operational base in the Chapare region of the country[7][8] as did the Bolivian coca eradication and substitution agency Direccion de Reconversion Agricola (DIRECO). UMOPAR and the US conducted the joint Operation Blast Furnace in 1986, in an unsuccessful effort to eradicate cocaine processing labs from the Chapare.[9] US personnel and US-hired Bolivians actively directed antidrug operations in the region.[10] In 1988, the DEA and UMOPAR began the antinarcotics Operation Snowcap, while US Border Patrol agents supported Bolivia police checkpoints on roads in the Chapare.[11] US Army Special Forces troops conducted training courses for UMOPAR troops at the base camp of Chimoré, east of Villa Tunari, beginning in 1987.[11]

From 1985 to 1988, just as government policy increasingly focused on the eradication of coca crops, coca growers unions grew in size and activity in Bolivia.[12] Coca growers demanded that treatment of their crops be detached from the criminalization of the cocaine trade.[12] They carried out marches, demonstrations, hunger strikes, and road blockades in support of their demands.[12] Unionized coca growers’ hostility towards DIRECO and the UMOPAR increased throughout 1988 in the leadup to the massacre.[13] In early 1988, DIRECO staff used herbicides to destroy coca in violation of agreements reached between the government and farmers.[13] Bolivian coca growers in the region alleged that in addition to providing logistical assistance to UMOPAR the DEA was also responsible for this chemical eradication of their crops.[14]

Coca growers mobilization in 1988

editFrom late May onward, Chapare coca growers mobilized in opposition to herbicidal eradication and the pending passage of a law that would criminalize coca leaf production in their region.[15] On 30 May, farmers in the Chapare town of Eterazama warned journalists that the continued use of herbicides would lead them to confront DEA intruders in the region and coca producer leader Rene Santander likewise demanded that DEA agents leave the region or face organized resistance. On 11 June, farmers in Villa Tunari threatened to take over coca-eradication facilities by force if the Bolivian congress approved the Ley 1008 legislation that would classify coca-growers as cocaine traffickers. On 15 June, meetings between growers and the government ended without reaching any resolution on these issues and DIRECO officials soon went on collective vacation, aware of the farmers’ intentions to take direct action.[15]

27 June 1988

editFollowing a night of meetings in Villa Tunari,[16] peasant leaders made the decision to visit the DIRECO facility that was adjacent to the UMOPAR barracks in order to address directly the agency’s use of herbicides.[15] Union leader Julio Rocha[13] led what is variously reported as a group of 3,000,[17] 4,000,[18] or 5,000[19][20] coca-growers to the facilities. Finding the DIRECO compound unoccupied,[21] Rocha and three other peasant leaders went to the UMOPAR guard post and requested to speak with the commander in charge, Colonel José Luis Miranda, who authorized their entry while the rest of the farmers waited at the entrance and at the neighboring DIRECO facility.[22] While talks took place between the peasant leaders and the Colonel, the peasants remained calm and peaceful but UMOPAR troops nonetheless became increasingly nervous due to the peasants’ large numbers.[23]

At this time, the coca-grower Eusebio Tórrez Condori was shot and killed near the entrance to the DIRECO facility and dozens of growers began to enter the UMOPAR camp to report this event to their leaders who were at that time still meeting with the Colonel.[24] UMOPAR troops retreated and eventually between 400 and 600 of the coca-growers gained entrance to the camp.[24] Attempting to calm the increasingly tense situation, the UMOPAR Colonel promised to establish a committee to investigate the killing committed by DIRECO personnel[15] and reached a verbal commitment of mutual non-aggression with the peasant leader Julio Rocha.[25]

Despite a multisectoral research commission’s findings that the gathered peasants had up until this point shown neither violence or aggression,[24] an UMOPAR soldier radioed for reinforcements from the nearby town of Chimoré.[22] Upon arrival to Villa Tunari at 10:30 am, the reinforcement UMOPAR forces under the command of Major Primo Peña acted in what has been described as "disproportionate" and "brutal" violence.[19] Arriving in several vans, with DEA agents reportedly leading them,[20][26] the reinforcements opened fire on the peasants, killing Felicidad Mendoza de Peredo in the adjacent market grounds[24] and also firing tear gas into the market, school, and a health clinic.[22] The Villa Tunari UMOPAR troops likewise began shooting at the gathered peasants at this time.[24] Eyewitnesses claimed that as many as twenty peasants attempting to escape the crossfire by fleeing from the back of the camp fell 30 meters into the San Mateo River and drowned.[24] Other witnesses affirmed that they saw troops throw four unidentified peasants into the river.[20]

Some of the events in Villa Tunari were video recorded. Journalist Jo Ann Kawell summarized the "hour-long video tape made by a crew from a local television station":

Hundreds of marchers, dressed in shabby work clothes and carrying no visible arms, not even sticks, approach the post. Nervous police, wearing camouflage uniforms and armed with automatic rifles,block the marchers' advance. A union leader asks permission for the group to enter and go to the eradication program office located on the site. Shots ring out. One farmer falls dead, another is wounded. Several farmers, including the wounded man, point out the police agent who fired. A police official promises that his men's arms will not be used again "against campesinos. Only to fight drug traffickers." But many more shots are heard as the police push the marchers off the grounds and far down the road.[27]

These events resulted in the deaths of coca-growers Mario Sipe (drowned),[22][15] Tiburcio Alanoca (drowned),[22] Luis Mollo,[24] Sabino Arce,[24] Trifon Villarroel,[24] and Emigdio Vera Lopez,[24] whose bodies were all recovered. Calixto Arce, recorded as missing by the multisectoral commission, is among the dead as reported in 2018.[24][16][26] Multiple sources, including the state-run newspaper Cambio, report three additional deaths by drowning, whose bodies were never found.[16]

Eleven protesters were arrested during day's events.[28]

Allegations that the protesters were armed

editInformation Minister Herman Antelo publicly alleged that the peasant protesters were armed with carbines, revolvers, and dynamite cartridges, obligating the police to act in defense of the law and themselves.[29] Antelo claimed that three of the eleven arrested protesters were armed.[28] The multisectoral commission concluded that "not only does not a single piece of evidence prove this, but also the testimony of persons of religious [observers] is unanimous in signally that they did not see anyone either drunk or armed. This is corroborated by the images filmed on 27 June."[30]

Antelo also stated that the police "did not fire shots at the crowd, but rather at the air" and claimed that one police officer was killed.[28] The multisectoral commission reported that, "The announced death of a soldier on June 27 was denied to this Commission by the very officials and soldiers of UMOPAR [in] Villa Tunari. That soldier had died days before the events."[24]

DEA involvement controversy

editThe direct role of the US Drug Enforcement Administration officers in the violence is disputed. A witness to the shooting of Felicidad Mendoza de Peredo in the market stated that she was killed by "a gringo" shooting at point-blank range.[31] Evo Morales recalled that "I was a witness to how the gringos from the DEA fired upon us and the Villa Tunari massacre was made. Later, we recovered cadavers drowned in the river and others with bullet wounds. It was all for the defense of the coca leaf against Law 1008."[32] In a 1989 summary of the incident, the US State Department stated, "Five DEA agents were at the base, but they did not take part in the fighting and were not hurt."[33] Jo Ann Kawell, describing video evidence of the massacre wrote, "The farmers later charged that agents of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration had encouraged the police action. Nothing in the video seems to prove this, though, judging by their appearance, several men among the police could be North Americans."[34]

The multisectoral commission concluded that,

There is conclusive evidence that DEA agents and/or US military instructors participated in the reinforcement detachment from UMOPAR-CHIMORE. What has not been possible to objectively determine is whether they came to fire weapons or chemical agents against the peasants, as multiple denunciations affirm.[35]

According to Rensselaer W. Lee, "It was widely reported in the media that the reinforcements included DEA agents."[36]

Peter Andreas and Coletta Youngers wrote that, "The presence of DEA personnel in the police station at the time of the incident evoked bitter criticism of DEA interference in Bolivian internal affairs. As a result of such incidents, the perception of much of the population in Bolivia, as in the rest of the Andes, is that the DEA now plays the role of an occupation army."[37]

Aftermath

editAfter the massacre, UMOPAR troops continued their repression of protesters and the population of the Chapare. In Villa Tunari, American helicopters flew overhead as houses were raided. Residents Danitza Guzmán de Gordillo, Francisco Choque Sausiri and others were arrested and several union and civic leaders kidnapped in what the Multisectoral Commission later described as a climate of "fear, anxiety and intimidation".[24] Leaders of the Federación Especial de Agricultores del Trópico described to the newspaper Ultima Hora how "they came back to repress the townspeople of Villa Tunari, in the presence of civic leaders and local authorities," as soon as journalists covering the massacre had left the town.[38] Municipal council leader José Villarroel Vargas attributed the repression to "North American military troops who entered" Villa Tunari on the day of the massacre.[38]

This violence next spread to nearby towns in the Chapare, where other peasants were preparing their own protests.[39] Peasants on the Villa Tunari-Sinahota road and the Sinahota-Chimoré road were beaten by UMOPAR troops and teargassed from overhead helicopters. For example, at the intersection of the road to Aurora Ala, UMOPAR troops beat up Aquilino Montaño and Carlos Rodrigues while teargassing others. At the intersection of the Lauca Ñ road UMOPAR troops also beat and kicked peasants.[24] An unknown number were arrested; the multisectorial commission concluded "the detentions … had no justified reason."[26][24]

Later the same afternoon, a town hall was held in nearby Ivirgarzama to analyze the morning’s events in Villa Tunari. At 4:00 pm UMOPAR troops and helicopters (identified as DEA aircraft by locals) began to tear gas and machine gun those gathered.[40] Román Colque Oña, Margarita Ávila Panozo, and three-year-old Grover Quiroz were transported to Cochabamba with gunshot wounds.[24][26] In the coming days, security forces would continue beatings, the use of tear gas, and helicopter fly-overs in Ivirgarzama as well as Parajtito.[24]

On 30 June, the Central Obrera Boliviana (COB), the country's labor federation, carried out a 48-hour strike in protest of the killings in Villa Tunari; the government declared the strike to be illegal.[41]

Evo Morales, later president of Bolivia from 2006 to 2019, was present at the confrontation.[32][16] At the time of the massacre, Morales was serving as the executive of the Central 2 de Agosto, a local union of coca growers.[16] Soon afterwards, Morales was elected to head the Federation of Peasant Workers of the Tropic of Cochabamba as part of a slate known as the Broad Front of Anti-Imperialist Masses (Frente Amplio de Masas Anti-Imperialistas).[42] On June 27, 1989, Morales spoke at the one-year anniversary commemoration of the massacre. The following day, UMOPAR agents beat Morales up, leaving him in the mountains to die, but he was rescued by other union members.[43][44]

Passage of coca law

editThe Coca and Controlled Substances Regime Law (Spanish: Ley 1008, Ley del Regimen de la Coca y Substancias Controladas) was passed on 19 July 1988.[45] The law outlawed coca production outside of specified zones, making all coca growing in the Chapare subject to eradication without compensation. However, some US priorities were excluded from the law: defoliants, herbicides, and aerial spraying of crops were prohibited from being used in eradicating coca, and areas including the Chapare were placed into a transitional category where coca growers were entitled to economic support during the process of eradication.[45] According to Peter Andreas and Coletta Youngers, the law "outlawed herbicide use in an apparent attempt to appease protesters."[46][47]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Gutiérrez Aguilar, Raquel (2008). Los ritmos del Pachakuti: Movimiento y levantamiento indígena-popular en Bolivia. La Paz, Bolivia: Ediciones Yachaywasi : Textos Rebeldes. p. 165.

- ^ Madeline Barbara Léons, Harry Sanabria, ed. (1997). Coca, cocaine, and the Bolivian reality. SUNY Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-7914-3482-6.

- ^ Gomez, Luis (February 28, 2006). "Bolivia's Political Moment, Part II: Contradictions in Response to Viceroy Greenlee". Narco News. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- ^ "Bolivia: Cocaleros Sign Truce". WEEKLY NEWS UPDATE ON THE AMERICAS. No. 266. NICARAGUA SOLIDARITY NETWORK OF GREATER NEW YORK. October 6, 2002. Archived from the original on July 1, 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- ^ "Comisión viaja hoy al Chapare". Ultima Hora. 1988-06-30.

- ^ Córtez Hurtado, Róger (1993). "Coca y cocaleros en Bolivia". In Hermes Tovar Pinzón (ed.). La coca y las economias de exportación en América Latina. Albolote, Spain: Universidad Hispanoamericana. Santa María de la Rábida. p. 142. ISBN 84-8010-017-6.

UMOPAR … es una unidad para-policial, militarizada, que se especializa en la represión antidrogas

- ^ Painter, James (1994). Bolivia and coca: a study in dependency. United Nations University Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-92-808-0856-8.

- ^ Menzel, Sewall H. (1997). Fire in the Andes: U.S. Foreign Policy and Cocaine Politics in Bolivia and Peru. University Press of America. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-7618-1001-8.

- ^ Malamud-Goti, Jaime (1990). "Soldiers, Peasants, Politicians and the War on Drugs in Bolivia Recent Developments Articles". American University Journal of International Law and Policy. 6 (1): 41–42. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

Operation Blast Furnace was designed to lower the market price of the coca leaf by destroying cocaine laboratories, thus reducing the demand for raw coca. On July 18, 1986, Bolivian troops, aided by American pilots, moved into the Beni, Chapare, and Santa Cruz regions. Before the troops arrived, however, the traffickers deserted all the drug processing labs, and the troops found no narcotics.

- ^ Christian, Shirley (1986-09-24). "Bolivia's Coca Growers: Bitterness Over Lost Crop". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

Despite her perception of the Leopards as being responsible for the raids, interviews with others in the region suggested that civilians employed by the United States Government, both American and Bolivian, play a major role by pushing or nudging the Bolivian policemen into action day by day. … Almost every time that the one Bolivian helicopter assigned to the anti-drug effort in the Chapare takes to the air in search of stamping pits, an American or Bolivian working for the United States Government goes along to help spot targets for ground troops to raid.

- ^ a b Bolivia: A Country Study. Washington, DC: Library of Congress. 1991. p. 264.

- ^ a b c Córtez Hurtado, Róger (1993). "Coca y cocaleros en Bolivia". In Hermes Tovar Pinzón (ed.). La coca y las economias de exportación en América Latina. Albolote, Spain: Universidad Hispanoamericana. Santa María de la Rábida. p. 141. ISBN 84-8010-017-6.

- ^ a b c Malamud-Goti, Jaime (1990-01-01). "Soldiers, Peasants, Politicians and the War on Drugs in Bolivia". American University International Law Review. 6 (1): 45.

- ^ Malamud-Goti, Jaime (1990). "Soldiers, Peasants, Politicians and the War on Drugs in Bolivia Recent Developments Articles". American University Journal of International Law and Policy. 6 (1): 45. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

Peasants alleged that DEA officials in the Chapare instructed the DIRECO staff to use the herbicides.

- ^ a b c d e Centro de Documentación e Información (CEDOIN) (1988). "Villa Tunari: Dos Versiones Sobre Un Mismo Hecho". Informe "R". No. 153/154.

- ^ a b c d e Chambi O., Víctor Hugo (2018-06-27). "La Masacre de Villa Tunari Tuvo El Sello de La Intromisión de EEUU". Cambio. Archived from the original on 2018-06-28.

- ^ US Department of State. Bureau of Diplomatic Security (1989). Significant Incidents of Political Violence Against Americans 1988. Washington: Department of State. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-4289-6573-7.

- ^ "Cinco Muertos Habrían Causado Enfrentamientos En El Chapare". Los Tiempos. Cochabamba. June 28, 1988.

- ^ a b Centro de Documentación e Información (CEDOIN) (1988). "Represión en Villa Tunari: Cuidado con la guerra de la coca". Informe "R". No. 152.

- ^ a b c Azcui, Mabel (1988-06-29). "La 'guerra de la cocaína' en Bolivia". El País. Madrid. ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- ^ Long, William R. (1988-08-29). "Peasants' Way of Life : Coca Leaf--Not Just for Getting High". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- ^ a b c d e "Tensa Calma Reina En Toda La Región Del Chapare". Ultima Hora. La Paz. 1988-06-29.

- ^ "Comisión Investigadora Multisectorial". Informe "R". No. 153/154. 1988.

Cuando la columna llegó … una delegación de cuatro dirigentes campesinos solicitó entrevistarse con el Comandante, Cnl. José Luis Miranda, quien ese día estaba al mando … El Comandane de UMOPAR autorizó el ingerso de la reducida comitiva después que fueron revisados de no partara armas. El resto de los campesinos se quedó en la entrada del cuartel y de las vecinas instalaciones de DIRECO.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Comisión Investigadora Multisectorial". Informe "R". No. 153/154. 1988.

- ^ “Tensa Calma Reina En Toda La Región Del Chapare”; Azcui, “La ‘guerra de la cocaína’ en Bolivia”; Centro de Documentación e Información (CEDOIN), “Represión En Villa Tunari: Cuidado Con La Guerra de La Coca,” 3

- ^ a b c d Reyes Zárate, Raúl (2018-06-28). "A 30 años de la masacre de Villa Tunari". Rebelión. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- ^ Kawell, Jo Ann (1989). "Under the Flag of Law Enforcement". NACLA Report on the Americas. 22 (6): 25–40. doi:10.1080/10714839.1989.11723283.

- ^ a b c "Ministro de Informaciones: Asalto al cuartel de UMOPAR originó los sucesos del Chapare". Ultima Hora. La Paz. 1988-06-30.

- ^ "Versión del Gobierno: Extrema izquierda y traficantes son responsables de incidentes". Los Tiempos. Cochabamba. 1988-06-29.

- ^ "Respecto al supuesto armamento de los campesinos o de que estuiveron ebrios, no sólo no existe una sola prueba sino que el testimonio de personas y de los religiosos es unánime en señalar que no se vio a nadie ebrio por las imágenes filmadas el 27 de junio." "Comisión Investigadora Multisectorial". Informe "R". No. 153/154. 1988.

- ^ Cortez Hurtado, Roger (1992). La Guerra de la coca: una sombra sobre los Andes. La Paz: CID, Centro de Informacion para el Desarrollo : FLACSO, Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales. p. 128.

- ^ a b "He sido testigo de cómo los gringos de la DEA nos dispararon y se produjo la masacre en Villa Tunari. Después recogimos cadáveres ahogados en el río y otros con orificios de bala. Todo era por la defensa de la hoja de coca contra la Ley 1008" "Evo rinde homenaje a mártires de la masacre de Villa Tunari". Cambio. 2009-06-16. Archived from the original on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ^ US Department of State. Bureau of Diplomatic Security. 1989. Significant Incidents of Political Violence Against Americans 1988. Washington: Department of State.

- ^ Kawell, Jo Ann (1989). "Under the Flag of Law Enforcement". NACLA Report on the Americas. 22 (6): 25–40. doi:10.1080/10714839.1989.11723283.

- ^ "Comisión Investigadora Multisectorial". Informe "R". No. 153/154. 1988.

Hay evidencias concluyentes de que en el destacamento de UMOPAR-CHIMORE partiparon agentes de la DEA y/o instructores militares norteamericanos. Lo que no ha sido posible determinar objetivamente es si llegaron a disparar armas y/o agentes químicos contra los campesinos tal cual afirman múltiples denuncias.

- ^ Lee, Rensselaer W. (1991-01-01). The White Labyrinth: Cocaine and Political Power. Transaction Publishers. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-1-4128-3963-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Andreas, Peter; Youngers, Coletta (1989). "U. S. Drug Policy and the Andean Cocaine Industry". World Policy Journal. 6 (3): 550. ISSN 0740-2775. JSTOR 40209118.

- ^ a b "Paulatinamente retorna la tranquilidad en el Chapare". Ultima Hora. La Paz. 1988-06-30.

- ^ Ataque a población de Ivirgarzama . Pero el 27 de junio , el ataque instruido por el Gobierno y la DEA también alcanzó a otras poblaciones del Trópico , sobre todo a Ivirgarzama y Chimoré , donde se realizaban preparativos para el inicio de movilizaciones en contra de la Ley 1008 y denunciando el inicio de la 'guerra biológica.' Salazar Ortuño, Fernando (2008). Kawsachun coca. Cochabamba?: UMSS, IESE, Instituto de Estudios Sociales y Económicos : UDESTRO, Unidad de Desarrollo Económico y Social de Trópico. p. 142. ISBN 978-99954-0-300-3.

- ^ Centro de Documentación e Información (CEDOIN) (1988). "2ª Quincena de junio". Informe "R". No. 152.

Población de Ivirgazama denuncia que helicóptero de DEA ametralló concentración campesina dejando saldo de tres heridos.

- ^ "Hoy comienza paro de la COB que fue declarado ilegal". Ultima Hora. 1988-06-30.

- ^ "In 1988, shortly after the Massacre of Villa Tunari, Morales and a group of associates, who called themselves the “Anti-Imperial Front” (Frente Amplio de Masas Anti-Imperialistas—FAMAI), were elected to the leadership." Grisaffi, Thomas (2018-12-31). Coca Yes, Cocaine No: How Bolivia's Coca Growers Reshaped Democracy. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-1-4780-0433-2.

- ^ Sivak, Martín (2010). Evo Morales: The extraordinary rise of the first indigenous president of Bolivia. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-230-62305-7.

- ^ Terán, Néstor Taboada (2006). Tierra mártir: del socialismo de David Toro al socialismo de Evo Morales. Editora H & P. p. 100.

- ^ a b Thoumi, Francisco E. (2003). Illegal drugs, economy and society in the Andes. Woodrow Wilson Center Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-8018-7854-1.

Nevertheless, there was substantial accommodation: aerial spraying was banned as well as the use of defoliants and herbicides in coca eradication efforts (Malamud-Goti 1994). In addition, international funding was required for alternative development and peasant compensation programs in the Chapare.

- ^ Andreas, Peter; Youngers, Coletta (1989). "U. S. Drug Policy and the Andean Cocaine Industry". World Policy Journal. 6 (3): 529–562. ISSN 0740-2775. JSTOR 40209118.

- ^ Malamud-Goti, Jaime (1990). "Soldiers, Peasants, Politicians and the War on Drugs in Bolivia Recent Developments Articles". American University Journal of International Law and Policy. 6 (1): 46. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

This law restricted the means of eradication to inefficient manual procedures. Thus, coca growers have demonstrated that as an organized force, they have enough political power to influence and restrain the Bolivian government.