Bruce Duncan "Utah" Phillips (May 15, 1935 – May 23, 2008)[1] was an American labor organizer, folk singer, storyteller and poet. He described the struggles of labor unions and the power of direct action, self-identifying as an anarchist.[2] He often promoted the Industrial Workers of the World in his music, actions, and words.

Utah Phillips | |

|---|---|

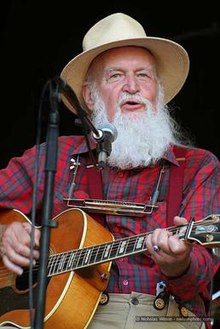

Utah Phillips, 2006 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Bruce Duncan Phillips |

| Born | May 15, 1935 Cleveland, Ohio |

| Died | May 23, 2008 (aged 73) Nevada City, California |

| Genres | Folk music |

| Occupation(s) | Songwriter, performer, raconteur |

| Website | thelongmemory.com |

Early years

editPhillips was born in Cleveland to Edwin Deroger Phillips and Frances Kathleen Coates. His father, Edwin Phillips, was a labor organizer, and his parents' activism influenced much of his life's work. Phillips was a card-carrying member of the Industrial Workers of the World (Wobblies), which were headquartered in Chicago. His parents divorced and his mother remarried. Phillips was adopted at the age of five by his stepfather, Syd Cohen, who managed the Hippodrome Theater in Cleveland, one of the last vaudeville houses in the city. Cohen moved the family to Salt Lake City, Utah, where he managed the Lyric Theater, another vaudeville house. Phillips attributes his early exposure to vaudeville through his stepfather as being an important influence on his later career.[3]

Phillips attended East High School in Salt Lake City, where he was involved in the arts and plays.[4] He served in the United States Army for three years in the 1950s. Witnessing the devastation of post-war Korea greatly influenced his social and political thinking. After discharge from the army, Phillips rode the railroads, and wrote songs.[5]

Career

editWhile riding the rails and tramping around the west, Phillips returned to Salt Lake City, where he met Ammon Hennacy from the Catholic Worker Movement. He gave credit to Hennacy for saving him from a life of drifting to one dedicated to using his gifts and talents toward activism and public service.[4] Phillips assisted him in establishing a mission house of hospitality named after the activist Joe Hill.[6][7] Phillips worked at the Joe Hill House for the next eight years, then ran for the U.S. Senate as a candidate of Utah's Peace and Freedom Party in 1968. He received 2,019 votes (0.5%) in an election won by Republican Wallace F. Bennett. He also ran for president of the United States in 1976 for the Do-Nothing Party.[8]

He adopted the name U. Utah Phillips in keeping with the hobo tradition of adopting a moniker that included an initial and the state of origin, and in emulation of country vocalist T. Texas Tyler.[9]

Phillips met folk singer Rosalie Sorrels in the early 1950s, and remained a close friend of hers. Sorrels started playing the songs that Phillips wrote, and through her his music began to spread. After leaving Utah in the late 1960s, he went to Saratoga Springs, New York, where he was befriended by the folk community at the Caffè Lena coffee house. He became a staple performer there for a decade, and would return throughout his career.

Phillips was a member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW or Wobblies). His views of unions and politics were shaped by his parents, especially his mother who was a labor organizer for the CIO. But Phillips was more of a Christian anarchist and a pacifist, so found the modern-day Wobblies to be the perfect fit for him, an iconoclast and artist. In recent years, perhaps no single person did more to spread the Wobbly gospel than Phillips, whose countless concerts were, in effect, organizing meetings for the cause of labor, unions, anarchism, pacifism, and the Wobblies. He was a tremendous interpreter of classic Wobbly tunes including "Hallelujah, I'm a Bum," "The Preacher and the Slave," and "Bread and Roses."

An avid trainhopper, Phillips recorded several albums of music related to the railroads, especially the era of steam locomotives. His 1973 album, Good Though!, is an example, and contains such songs as "Daddy, What's a Train?" and "Queen of the Rails" as well as what may be his most famous composition, "Moose Turd Pie"[10] wherein he tells a tall tale of his work as a gandy dancer repairing track in the Southwestern United States desert.

In 1991 Phillips recorded, in one take, an album of song, poetry and short stories entitled I've Got To Know, inspired by his anger at the first Gulf War. The album includes "Enola Gay," his first composition written about the United States' atomic attack on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Phillips was a mentor to folk singer Kate Wolf. In 1998, he was the first recipient of the Kate Wolf Memorial Award from the World Folk Music Association.[11] He recorded songs and stories with Rosalie Sorrels on a CD called The Long Memory (1996), originally a college project "Worker's Doxology" for 1992 'cold-drill Magazine' Boise State University. His admirer, Ani DiFranco, recorded two CDs, The Past Didn't Go Anywhere (1996) and Fellow Workers (1999), with him.[12] He was nominated for a Grammy Award for his work with DiFranco. His "Green Rolling Hills" was made into a country hit by Emmylou Harris, and "The Goodnight-Loving Trail" became a classic as well, being recorded by Ian Tyson, Tom Waits, and others.

Later years and death

editThough known primarily for his work as a concert performer and labor organizer, Phillips also worked as an archivist, dishwasher, and warehouse-man.[13]

Phillips was a member of various socio-political organizations and groups throughout his life. A strong supporter of labor struggles, he was a member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers (Mine Mill), and the Travelling Musician's Union AFM Local 1000. In solidarity with the poor, he was also an honorary member of Dignity Village, a homeless community. A pacifist, he was a member of Veterans for Peace and the Peace Center of Nevada County.[13]

In his personal life, Phillips enjoyed varied hobbies and interests. These included Egyptology; amateur chemistry; linguistics; history (Asian, African, Mormon and world); futhark; debate; and poetry. He also enjoyed culinary hobbies, such as pickling, cooking and gardening.[13]

He married Joanna Robinson on July 31, 1989, in Nevada City.[13]

Phillips became an elder statesman for the folk music community, and a keeper of stories and songs that might otherwise have passed into obscurity. He was also a member of the great Traveling Nation, the community of hobos and railroad bums that populates the Midwest United States along the rail lines, and was an important keeper of their history and culture. He also became an honorary member of numerous folk societies in the US and Canada.[13]

When Kate Wolf grew ill and was forced to cancel concerts, she asked Phillips to fill in. Suffering from an ailment which makes it more difficult to play guitar, Phillips hesitated, citing his declining guitar ability. "Nobody ever came just to hear you play," she said. Phillips told this story as a way of explaining how his style over the years became increasingly based on storytelling instead of just songs. He was a gifted storyteller and monologist, and his concerts generally had an even mix of spoken word and sung content. He attributed much of his success to his personality. "It is better to be likeable than talented," he often said, self-deprecatingly.

From 1997 to 2001, Phillips hosted his own weekly radio show, Loafer's Glory: The Hobo Jungle of the Mind, originating on KVMR and nationally syndicated. The show was suspended after 100 episodes due to lack of funding.

Phillips lived in Nevada City, California, for 21 years where he worked on the start-up of the Hospitality House, a homeless shelter,[14] and the Peace and Justice Center. "It's my town. Nevada City is a primary seed-bed for community organizing."[5]

In August 2007, Phillips announced that he would undergo catheter ablation to address his heart problems.[15] Later that autumn, Phillips announced that due to health problems he could no longer tour.[16] By January 2008, he decided against a heart transplant.[5]

Phillips died May 23, 2008, in Nevada City, California, from complications of heart disease, eight days after his 73rd birthday,[1] and is buried in Forest View Cemetery in Nevada City.[5]

Personal papers

editArchival materials related to Phillips' personal and professional life are open for research at the Walter P. Reuther Library in Detroit, Michigan. The papers include correspondence, interviews, writings, notes, contracts, flyers, publications, articles, clippings, photographs, audiovisual recordings, and other materials.[17]

Discography

edit|

Solo albums

|

Other albums

|

Bibliography

edit- 1973 Starlight on the Rails and Other Songs (Wooden Shoe)

- 2011 Starlight on the Rails and Other Songs (2nd edition, expanded) (Dream Garden Press)

References

edit- ^ a b "Utah Phillips Has Left the Stage" Archived August 21, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, KVMR, Nevada City, California, May 24, 2008. Retrieved 24 May 2008.

- ^ "Voting For the First Time". Retrieved December 27, 2007.

I'm an anarchist and I've been an anarchist many, many years.

- ^ Phillips, Utah. clownzen.com Archived December 18, 2013, at the Wayback Machine June 2002 interview. Retrieved December 7, 2013.

- ^ a b "Folk Revival in Salt Lake City?", folkworks.org. Retrieved 7 December 2013

- ^ a b c d Pelline, Jeff; Butler, Pat (May 26, 2008). "From hobo to fame". The Union. Archived from the original on May 30, 2008. Retrieved April 14, 2018.

- ^ Rattler, Fast. "Utah Phillips on the Catholic Worker, Polarization, and Songwriting". Archived from the original (interview) on December 12, 2007. Retrieved March 1, 2008.

- ^ Crane, Carolyn. "Interview with Utah Phillips". Archived from the original (interview, Z Magazine) on January 20, 2008. Retrieved March 1, 2008.

- ^ Hawthorn, Tom. "Unapologetic Wobbly folk singer found a second home in Canada". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved June 16, 2008.

- ^ Direct quotation from his biography in The Washington Post, May 30, 2008.

- ^ Phillips, Bruce. "Moose Turd Pie". Archived from the original (mp3) on June 13, 2007. Retrieved January 12, 2008.

- ^ Noble, Richard E. (2009). Number #1 : the story of the original Highwaymen. Denver: Outskirts Press. p. 265. ISBN 9781432738099. OCLC 426388468.

- ^ Merritt, Stephanie (April 28, 2001). "Life Support". The Guardian.

- ^ a b c d e "Bruce Phillips". The Union. May 29, 2008. Archived from the original on May 24, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2008.

- ^ Russell, Tony (June 24, 2008). "Utah Phillips: Folksinger, songwriter and bard of the last days of the US railroad". The Guardian. London. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- ^ Phillips, U.Utah. "The Latest From FW Utah Phillips" (announcement). Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- ^ Phillips, Utah. "Retirement Announcement". Archived from the original (mp3) on February 27, 2008. Retrieved March 1, 2008.

- ^ Pillen, Dallas. "Collection Spotlight: The Utah Phillips Papers". Walter P. Reuther Library. Wayne State University. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

External links

edit- Folksinger, Storyteller, Railroad Tramp Utah Phillips Dead at 73 – Picture gallery and official obituary provided by family.

- Biography from the 1997 Folk Alliance Lifetime Achievement Awards

- Summer 2005 Interview in "Unlikely Stories"

- Simon, Scott (May 31, 2008). "Remembering Utah Phillips". Weekend Edition. NPR. (Radio broadcast)

- The “Golden Voice of the Great Southwest”, Utah Phillips memorial page on Democracy Now!

- cover performance of "All Used Up" by Suzanne Langille in London, May 14, 2011 on YouTube.

- Utah Phillips at IMDb