Ursula Southeil (c. 1487 – 1561); also variously spelt as Southill, Soothtell,[4] Sontheil,[5][6] or Sonthiel,[7] popularly known as Mother Shipton, was an English soothsayer and prophetess according to English folklore.

Mother Shipton | |

|---|---|

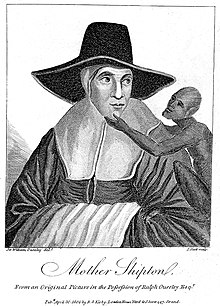

An 1804 portrait of Shipton with a monkey or familiar, taken from an oil painting dating from at least a century earlier[1] | |

| Born | Ursula Southeil c. 1486-8[2] Knaresborough, North Yorkshire, England |

| Died | 1561 (aged 72–75) |

| Other names | Ursula Soothtell, Ursula Sontheil, Ursula Sonthiel[3] |

| Occupation(s) | Fortune-teller, prophetess |

She has sometimes been described as a witch and is associated with folklore involving the origin of the Rollright Stones of Oxfordshire. A king and his men were said to have transformed to stone after failing her test, as reported by William Camden in a rhyming account in 1610.[8][9]

The first known edition of her prophecies was printed in 1641, eighty years after her reported death. This timing suggests that what was published was a legendary or mythical account. It contained numerous mainly regional predictions and only two prophetic verses.[10]

One of the most notable editions of her prophecies was published in 1684.[10] It gave her birthplace as Knaresborough, Yorkshire, in a cave now known as Mother Shipton's Cave.[a] The book reputed Shipton to be hideously ugly, and that she had married Toby Shipton, a local carpenter, near York in 1512, and told fortunes and made predictions throughout her life.

Personal life

editMother Shipton was born Ursula Southeil or Sonthiel, in 1486 or 1488 (though some sources claim she was born as early as 1448)[11] to 15-year-old Agatha Soothtale, allegedly in a cave outside the town of Knaresborough in North Yorkshire. The earliest sources of the legends of her birth and life were collected in 1667[12] by author and biographer Richard Head and later by J. Conyers in 1686.[4]

Both sources—1667 and 1686—state that Shipton was born during a violent thunderstorm, and was deformed and ugly, born with a hunchback and bulging eyes. The sources also state that Shipton cackled instead of crying after having been born, and as she did so, the previously raging storms ceased.[4]

The sources report Ursula's mother Agatha as a poor and desolate 15-year-old orphan, left with no means to support herself; having fallen under the influences of the Devil, Agatha engaged in an affair, resulting in the birth of Ursula.[12] Variations of this legend claim Agatha herself was a witch and summoned the Devil to conceive a child.

The true origin of Ursula's father is unknown, with Agatha refusing to reveal him; at one point, Agatha was forcibly brought before the local magistrate, but still refused to disclose his identity.[13] The scandalous nature of Agatha's life and Ursula's birth meant the two were ostracised from society and forced to live alone, in the same cave Ursula was born, for the first two years of Ursula's life.[14] Rumours that Agatha was a witch and Ursula the spawn of Satan were perpetuated, due to the cave's well-known skull-shaped pool, which turned things to stone.[15] The cave is known today as Mother Shipton's Cave; though the effects of the cave's pool are not those of true petrification, they closely resemble the process by which stalactites are formed, coating objects left in the cave with layers of minerals, and in essence hardening porous objects until they become hard and stone-like.[16]

According to 17th-century sources, after two years living alone in the Forest of Knaresborough, the abbot of Beverley intervened. The abbot removed them from the cave and secured Agatha a place in the Convent of the order of St. Bridget[4] in Nottinghamshire,[14] and Ursula a foster family in Knaresborough. Agatha and Ursula would never see each other again.

Developed from contemporary descriptions and depictions of her, it is likely Ursula had a large crooked nose and suffered from a hunchback and crooked legs. Physical differences acted as a visual reminder of the secretive events of her birth and the townspeople never forgot. She found acceptance with her foster family and a few friends, but Ursula was ultimately ostracised from the larger portion of people in town. She found sanctuary in the woods like her mother had and spent most of her childhood learning of plants and herbs and their medicinal properties.[17]

Legends of her childhood

editIt was claimed that when Ursula was two years old, she was left alone at home while her foster mother left to run errands. Her mother returned to find the front door wide open. Afraid of what might still be in the house, she called to her neighbours for assistance, and the group heard a loud wailing, like "a thousand cats in consort"[4] throughout the house. Ursula's cradle was found empty. After a frantic search throughout the house, her mother looked up to see Ursula naked and cackling, perched on top of the iron bar where the pot hooks were fastened above the fireplace.[4][14]

The source dating to 1686[4] tells of an event where the chief members of the parish were gathered together in a meeting. Ursula walked past the group running an errand for her mother, and the men stopped to mock her, calling out "hag face" and "The Devil's bastard".[4] Ursula kept walking to continue her errands but as the men sat back down, the ruff on the neck of one of the principal yeomen transformed and a toilet seat clapped down around his neck. The man next to him began to laugh, and as he did the hat he was wearing was suddenly replaced with a chamber pot. The gathered members of the parish began to laugh loudly enough that the Master of the house came running to see what was happening; when he tried to run through the door, he found himself blocked by a large pair of horns that had grown suddenly from his head. The source reports that the strange occurrences reverted to normal shortly afterwards, and that the townspeople took them as a sign not to publicly mock Ursula.

Adulthood

editAs Ursula grew so did her knowledge of plants and herbs and she became an invaluable resource for the townspeople as a herbalist. The respect she earned from her work gave her the opportunity to expand her social circle and it was then she met the local carpenter[4] Toby Shipton.[18]

When Ursula was 24 years old she and Toby Shipton were married.[18] From this point on Ursula adopted her husband's surname and became Mother Shipton. The people in town were shocked at their union and whispered of how he must have been bewitched to marry her.

About a month into her marriage a neighbour came to the door and asked for her help, saying she had left her door open and a thief had come in and stole a new smock and petticoat. Without hesitation Mother Shipton calmed her neighbour and said she knew exactly who stole the clothing and would retrieve it the next day. The next morning Mother Shipton and her neighbour went to the market cross. The woman who had stolen the clothing couldn't stop herself from putting the smock on over her clothes, the petticoat in her hand, and marching through town. When she arrived at the market cross she began dancing and danced straight for Mother Shipton and her neighbour all the while singing "I stole my Neighbours Smock and Coat, I am a Thief, and here I show't." When she reached Mother Shipton she took off the smock, handed it over, curtsied and left.[4]

Two years later, in 1514, Toby Shipton died, and the town believed Ursula to have been responsible for his death. The grief of losing her husband and the harsh words of the town prompted Ursula Shipton to move into the woods, and the same cave she had been born in, for peace. Here she continued to create potions and herbal remedies for people. Mother Shipton's name slowly became more and more well known, and people would travel far distances to see her and receive potions and spells.

As her popularity grew she grew bolder and revealed she could see the future. She started by making small prophecies involving her town and the people within, and as her prophecies came true she began telling prophecies of the monarchy and the future of the world. In 1537 King Henry VIII wrote a letter to the Duke of Norfolk where he mentions a "witch of York",[18] believed by some to be a reference to Shipton.

Prophecies

editThis section's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (June 2023) |

River Ouse

edit"Water shall come over Ouse Bridge, and a windmill shall be set upon a Tower, and a Elm Tree shall lie at every man's door".[14][19]

The River Ouse was the river next to York, and Ouse Bridge was the bridge over the river. This prophecy meant nothing to the people of York until the town got a piped water system. The system brought water across Ouse Bridge in pipes to a windmill that drew up the water into the pipes. The pipes they used were made out of Elm trees and the pipes came to every man's door delivering water throughout the town.

"Before Ouse Bridge and Trinity Church meet, what is built in the day shall fall in the night, till the highest stone in the church be the lowest stone of the bridge."

Not long after Mother Shipton uttered this prophecy did a huge storm fall on York. During the storm the steeple on the top of Trinity Church fell and a portion of the Ouse Bridge was destroyed and swept away by the river. Later when making repairs to the bridge, pieces that had previously been the steeple of the church were used as the foundation of the new section of the bridge. Effectively making Trinity Church and the Ouse Bridge what was built in the day and fell in the night, and the steeple from Trinity Church, the highest stone, be the foundation of the bridge, the lowest stone of the bridge.[14][20]

Prophecy of the end of times

editThe most famous claimed edition of Mother Shipton's prophecies foretells many modern events and phenomena. Widely quoted today as if it were the original, it contains over a hundred prophetic rhymed couplets. But the language is notably non-16th century. This edition includes the now-famous lines:

The world to an end shall come

In eighteen hundred and eighty one.[21]

This version was not published until 1862. More than a decade later, its true author, Charles Hindley, admitted in print that he had created the manuscript.[22]

This fictional prophecy was published over the years with different dates and in (or about) several countries. The booklet The Life and Prophecies of Ursula Sontheil better known as Mother Shipton (1920s, and repeatedly reprinted)[23] predicted the world would end in 1991.[24][25] (In the late 1970s, many news articles were published about Mother Shipton and her prophecy that the world would end—these accounts said it would occur in 1981.)[citation needed]

Technology

editAmong other well-known lines from Charles Hindley's fictional version (often quoted as if they were original) are:

Carriages without horses shall go;

And accidents fill the world with woe...

Iron in the water shall float,

As easy as a wooden boat.[21]

These lines hint at inventions not known in Shipton's time—but a reality in Hindley's—such as trains and iron ships, as well as at events such as wars and conflicts.[citation needed]

Historicity

editBased on contemporary references to her and countless resources detailing the events of her life, historians believe Mother Shipton was a real woman,[13][18][20] born in 1488 to an orphan fifteen-year-old girl named Agatha Soothtale in a cave in North Yorkshire outside of the town Knaresborough.[13][18][20] Based on how every contemporary record of her from the time references her appearance, she probably suffered from a hunchback and a large crooked nose, although much else regarding her appearance is conjecture. She made potions, herbal remedies, cast spells and prophesied the future.

In a possible reference to her existence, in 1537 Yorkshire, while Catholic people were rebelling against the dissolution of Catholic monasteries, Henry VIII wrote a letter to the Duke of Norfolk where he refers to a "witch of York".[18] It is believed that this letter is the earliest reference to the real Mother Shipton who would have been prophesying about Henry VIII at this time. In 1666 Samuel Pepys recorded in his diaries that, whilst surveying the damage to London caused by the 1666 Great Fire in the company of the Royal family, he heard them discuss Mother Shipton's prophecy of the event.[26]

The earliest account of Mother Shipton's prophecies was published in 1641, eighty years after her death. The story goes that the document of Mother Shipton's life was recorded by a woman named Joane Waller[14] who heard the story as a young girl and transcribed it as Mother Shipton spoke of her life. Mother Shipton never wrote anything down or published anything during her lifetime.

The cave where she lived is known as England's oldest tourist attraction and for hundreds of years people have trekked to see the cave where she was born. This cave's water has a mineral content so high anything placed in the pool will slowly be covered in layers of stone. Tourists will place items in the pool to later return and see it turned to stone. It is assumed that many of her prophecies were never written down, and many legends and prophecies accredited to her were created after her death to enhance the folk legend she had become. [27]

Legacy

editThe figure of Mother Shipton accumulated considerable folklore and legendary status. Her name became associated with many tragic events and strange goings-on recorded in the UK, North America and Australia throughout the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. Many fortune-tellers used her effigy and statue, presumably for purposes of association marketing. Many English pubs were named after her. Only two survive, one near her purported birthplace in Knaresborough and the other in Portsmouth. The latter has a statue of her above the door.

A caricature of Mother Shipton was used in early pantomime. Her appearance in pantomime was mentioned in a song from Yorkshire that was transcribed in the 18th century, and which reads (in part): "Of all the pretty pantomimes/ That have been seen or sung in rhimes,/Since famous Johnny Rich's times,/There's none like Mother Shipton."[28]

The Mother Shipton moth (Callistege mi) is named after her. Each wing's pattern resembles a hag's head in profile.

A fundraising campaign was started in 2013 to raise £35,000 to erect a statue of Shipton in Knaresborough. Completed in October 2017, the statue sits on a bench in the town's Market Square close to a statue of John Metcalf, an 18th-century road engineer known as Blind Jack.[29]

Mother Shipton is referred to in Daniel Defoe's A Journal of the Plague Year (1722), referring to the year 1665, when the bubonic plague erupted in London:

"These terrors and apprehensions of the people led them into a thousand weak, foolish, and wicked things, which they wanted not a sort of people really wicked to encourage them to: and this was running about to fortune-tellers, cunning-men, and astrologers to know their fortune, or, as it is vulgarly expressed, to have their fortunes told them, their nativities calculated, and the like... And this trade grew so open and so generally practised that it became common to have signs and inscriptions set up at doors: 'Here lives a fortune-teller', 'Here lives an astrologer', 'Here you may have your nativity calculated', and the like; and Friar Bacon's brazen-head, which was the usual sign of these people's dwellings, was to be seen almost in every street, or else the sign of Mother Shipton...."[30]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Along with the petrifying well and associated parkland, this property is now operated privately as a visitor attraction.

References

edit- ^ Smith, William (1883). Old Yorkshire. Longmans, Green & Co. p. 191.

- ^ Greenwood, Susan Witchcraft & Practical Magic. p.114. ISBN: 0-681-10391-4. London: Published by Hermes House for Anness Publishing, 2006.

- ^ Greenwood, Susan Witchcraft & Practical Magic. p.114. ISBN: 0-681-10391-4. London: Published by Hermes House for Anness Publishing, 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j The Strange and Wonderful History of Mother Shipton Plainly Setting Forth Her Prodigious Birth, Life, Death, and Burial, with an Exact Collection of All Her Famous Prophecys, More Compleat than Ever Yet before Published, and Large Explanations, Shewing How They Have All along Been Fulfilled to This Very Year. London: Printed for W.H. and sold by J. Conyers, 1686.

- ^ "Ursula Sontheil (1488-1561)". History and Women. 8 May 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ^ "The Life and Prophecies of URSULA SONTHEIL Better Known as MOTHER SHIPTON . Knaresborough, Yorkshire: Amazon.co.uk: J.C. Simpson: Books". Amazon.co.uk. 2 January 2011. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ^ Greenwood, Susan Witchcraft & Practical Magic. p.114. ISBN: 0-681-10391-4. London: Published by Hermes House for Anness Publishing, 2006.

- ^ "William Camden", Encyclopedia Britannia.

- ^ Anon. "Rollright Stones". BBC: Where I live: Oxford. BBC. Retrieved 19 June 2009.

- ^ a b Mother Shipton's Prophecies (Mann, 1989)

- ^ Greenwood, Susan Witchcraft & Practical Magic. p.114. ISBN: 0-681-10391-4. London: Published by Hermes House for Anness Publishing, 2006.

- ^ a b Head, Richard. The Life and Death of Mother Shipton: Giving a Wonderful Account of Her Strange and Monstrous Birth, Life, Actions and Death: with the Correspondence She Had with an Evil Spirit ..: with All Her Prophecies That Have Come to Pass, from the Reign of Henry VII ... to This Present Year 1694 ...: with Divers Not Yet Come to Pass ...: with the Explanation of Each Prophecy and Prediction. London: Printed for J. Back ..., 1667.

- ^ a b c "The Story". Mother Shipton's Cave. Accessed 21 October 2020. https://www.mothershipton.co.uk/the-story/ .

- ^ a b c d e f What'sHerName, Dr. Katie Nelson, and Olivia Meikle. "THE WITCH Mother Shipton". What'shername, 10 February 2020. https://www.whatshernamepodcast.com/mother-shipton/

- ^ "England's Oldest Tourist Attraction". Mother Shipton's Cave. Accessed 10 October 2020. https://www.mothershipton.co.uk/

- ^ "England's Oldest Attraction Turns Teddy Bears To Stone". youtube.com. Tom Scott (entertainer). 26 April 2021. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ "The Story". Mother Shipton's Cave. Accessed 21 October 2020. https://www.mothershipton.co.uk/the-story/

- ^ a b c d e f Simon, Dr. Ed. "Divining the Witch of York: Propaganda and Prophecy – 'Mother Shipton' in Medieval England". Brewminate, 22 August 2019. https://brewminate.com/divining-the-witch-of-york-propaganda-and-prophecy-mother-shipton-in-medieval-england/ .

- ^ Martha, Robert Nixon, and Shipton. "The Life and Prophecies of Mother Shipton". Chapter. In Prophecies of Robert Nixon, Mother Shipton, and Martha, the Gipsy, 103–96. London: Published for the booksellers, 1866.

- ^ a b c Harrison, William H. Mother Shipton Investigated: the Result of Critical Examination in the British Museum Library of the Literature Relating to the Yorkshire Sibyl. Folcroft, PA: Folcroft Library Editions, 1977.

- ^ a b Harrison, William Henry (1881). Mother Shipton investigated. The result of critical examination in the British Museum Library, of the literature relating to the Yorkshire sibyl. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Notes and Queries 1873-04-26: Vol 11 Iss 278". Internet Archive. 26 June 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "The Life and Prophecies of URSULA SONTHEIL Better Known as MOTHER SHIPTON: Books". Amazon.co.uk. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ^ Simpson, J. C. (24 August 2017). "The Life and Prophecies of URSULA SONTHEIL Better Known as MOTHER SHIPTON ". The Waverley Press – via Amazon.

- ^ "12 failed end of the world predictions, for 1990 to 1994". Religioustolerance.org. 3 November 1993. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ^ Entry for 20 October 1666, cited in Mother Shipton's Prophecies (Mann, 1989)

- ^ Araujo: Mother Shipton: Secrets, Lies and Prophesies (2010).

- ^ Ingledew, C. J. Davison (1860). The Ballads and Songs of Yorkshire, Transcribed from Private Manuscripts, Rare Broadsides, and Scarce Publications. London, UK: Bell and Daldy. p. 123.

- ^ "Knaresborough campaign for Mother Shipton statue". BBC News. 3 October 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ A Journal of the Plague Year (1772), Daniel Defoe, The Project Gutenberg EBook, 2006

External links

edit- Media related to Mother Shipton at Wikimedia Commons

- Works by or about Mother Shipton at Wikisource

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 988–989.

- Mother Shipton's Cave and Dropping Well

- Mother Shipton, Her Life and Prophecies, Mysterious Britain & Ireland