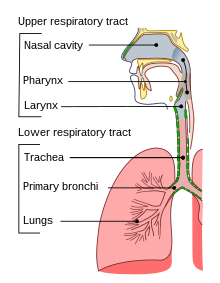

An upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) is an illness caused by an acute infection, which involves the upper respiratory tract, including the nose, sinuses, pharynx, larynx or trachea.[3][4] This commonly includes nasal obstruction, sore throat, tonsillitis, pharyngitis, laryngitis, sinusitis, otitis media, and the common cold.[5]: 28 Most infections are viral in nature, and in other instances, the cause is bacterial.[6] URTIs can also be fungal or helminthic in origin, but these are less common.[7]: 443–445

| Upper respiratory tract infection | |

|---|---|

| |

| Conducting passages | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Frequency | (2015)[1] |

| Deaths | 3,100[2] |

In 2015, 17.2 billion cases of URTIs are estimated to have occurred.[1] As of 2016, they caused about 3,000 deaths, down from 4,000 in 1990.[8]

Signs and symptoms

editIn uncomplicated colds, coughing and nasal discharge may persist for 14 days or more even after other symptoms have resolved.[6] Acute URTIs include rhinitis, pharyngitis/tonsillitis, and laryngitis often referred to as a common cold, and their complications: sinusitis, ear infection, and sometimes bronchitis (though bronchi are generally classified as part of the lower respiratory tract.) Symptoms of URTIs commonly include cough, sore throat, runny nose, nasal congestion, headache, low-grade fever, facial pressure, and sneezing.[9]

Symptoms of rhinovirus in children usually begin 1–3 days after exposure. The illness usually lasts 7–10 more days.[6]

Color or consistency changes in mucous discharge to yellow, thick, or green are the natural course of viral URTI and not an indication for antibiotics.[6]

Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis/tonsillitis (strep throat) typically presents with a sudden onset of sore throat, pain with swallowing, and fever. Strep throat does not usually cause a runny nose, voice changes, or cough.[citation needed]

Pain and pressure of the ear caused by a middle-ear infection (otitis media) and the reddening of the eye caused by viral conjunctivitis[10] are often associated with URTIs.

Cause

editIn terms of pathophysiology, rhinovirus infection resembles the immune response. The viruses do not cause damage to the cells of the upper respiratory tract, but rather cause changes in the tight junctions of epithelial cells. This allows the virus to gain access to tissues under the epithelial cells and initiate the innate and adaptive immune responses.[5]: 27

Up to 15% of acute pharyngitis cases may be caused by bacteria, most commonly Streptococcus pyogenes, a group A streptococcus in streptococcal pharyngitis ("strep throat").[11] Other bacterial causes are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Corynebacterium diphtheriae, Bordetella pertussis, and Bacillus anthracis[citation needed].

Sexually transmitted infections have emerged as causes of oral and pharyngeal infections.[12]

Diagnosis

edit| Symptoms | Allergy | URI (Common Cold) | Influenza (Flu) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Itchy, watery eyes | Common | Rare (conjunctivitis may occur with adenovirus) | Soreness behind eyes, sometimes conjunctivitis |

| Nasal discharge | Common | Common[6] | Common |

| Nasal congestion | Common | Common | Sometimes |

| Sneezing | Very common | Very common[6] | Sometimes |

| Sore throat | Sometimes (post-nasal drip) | Very common[6] | Sometimes |

| Cough | Sometimes | Common (mild to moderate, hacking)[6] | Common (dry cough, can be severe) |

| Headache | Uncommon | Rare | Common |

| Fever | Never | Rare in adults, possible in children[6] | Very common 37.8–38.9 °C (100–102 °F)(or higher in young children), lasting 3–4 days; may have chills |

| Malaise | Sometimes | Sometimes | Very common |

| Fatigue, weakness | Sometimes | Sometimes | Very common (can last for weeks, extreme exhaustion early in course) |

| Muscle pain | Never | Slight[6] | Very common (often severe) |

Classification

editA URTI may be classified by the area inflamed. Rhinitis affects the nasal mucosa, while rhinosinusitis or sinusitis affects the nose and paranasal sinuses, including frontal, ethmoid, maxillary, and sphenoid sinuses. Nasopharyngitis (rhinopharyngitis or the common cold) affects the nares, pharynx, hypopharynx, uvula, and tonsils generally. Without involving the nose, pharyngitis inflames the pharynx, hypopharynx, uvula, and tonsils. Similarly, epiglottitis (supraglottitis) inflames the superior portion of the larynx and supraglottic area; laryngitis is in the larynx; laryngotracheitis is in the larynx, trachea, and subglottic area; and tracheitis is in the trachea and subglottic area.[citation needed]

Prevention

editVaccination against influenza viruses, adenoviruses, measles, rubella, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, diphtheria, Bacillus anthracis, and Bordetella pertussis may prevent them from infecting the URT or reduce the severity of the infection.[citation needed]

Treatment

editTreatment comprises symptomatic support usually via analgesics for headache, sore throat, and muscle aches.[13] Moderate exercise in sedentary subjects with a naturally acquired URTI probably does not alter the overall severity and duration of the illness.[14] No randomized trials have been conducted to ascertain benefits of increasing fluid intake.[15]

Antibiotics

editPrescribing antibiotics for laryngitis is not a suggested practice.[16] The antibiotics penicillin V and erythromycin are not effective for treating acute laryngitis.[16] Erythromycin may improve voice disturbances after a week and cough after 2 weeks, but any modest subjective benefit is not greater than the adverse effects, cost, and the risk of bacteria developing resistance to the antibiotics.[16] Health authorities have been strongly encouraging physicians to decrease the prescribing of antibiotics to treat common URTIs because antibiotic usage does not significantly reduce recovery time for these viral illnesses.[16] A 2017 systematic review found three interventions which were probably effective in reducing antibiotic use for acute respiratory infections: C-reactive protein testing, procalcitonin-guided management, and shared decision-making between physicians and patients.[17] The use of narrow-spectrum antibiotics has been shown to be just as effective as broad-spectrum alternatives for children with acute bacterial URTIs, and has a lower risk of side effects in children.[18] Decreased antibiotic usage may also help prevent drug-resistant bacteria. Some have advocated a delayed antibiotic approach to treating URTIs, which seeks to reduce the consumption of antibiotics while attempting to maintain patient satisfaction. A Cochrane review of 11 studies and 3,555 participants explored antibiotics for respiratory tract infections. It compared delaying antibiotic treatment to either starting them immediately or to no antibiotics. Outcomes were mixed depending on the respiratory tract infection; symptoms of acute otitis media and sore throat were modestly improved with immediate antibiotics with minimal difference in complication rate. Antibiotic usage was reduced when antibiotics were only used for ongoing symptoms and maintained patient satisfaction at 86%.[19] In a trial involving 432 children with a URTI, amoxicillin was no more effective than placebo, even for children with more severe symptoms such as fever or shortness of breath.[20][21]

For sinusitis while at the same time discouraging overuse of antibiotics the CDC recommends:

- Target likely organisms with first-line medications: amoxicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanate

- Use the shortest effective course; should see improvement in 2–3 days. Continue treatment for 7 days after symptoms improve or resolve (usually a 10–14 day course).

- Consider imaging studies in recurrent or unclear cases; some sinus involvement is frequent early in the course of uncomplicated viral URI[6]

Cough medicine

editNo good evidence exists for or against the effectiveness of over-the-counter cough medications for reducing coughing in adults or children.[22] Children under 2 years old should not be given any type of cough or cold medicine due to the potential for life-threatening side effects.[23] In addition, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics, the use of cough medicine to relieve cough symptoms should be avoided in children under 4 years old, and the safety is questioned for children under 6 years old.[24]

Decongestants

editAccording to a Cochrane review, a single oral dose of nasal decongestant in the common cold is modestly effective for the short-term relief of congestion in adults; however, data on the use of decongestants in children are insufficient. Therefore, decongestants are not recommended for use in children under 12 years of age with the common cold.[19] Oral decongestants are also contraindicated in patients with hypertension, coronary artery disease, and history of bleeding strokes.[26][27]

Mucolytics

editMucolytics such as acetylcysteine and carbocystine are widely prescribed for upper and lower respiratory tract infection without chronic broncho-pulmonary disease. However, in 2013 a Cochrane review reported their efficacy to be limited.[28] Acetylcysteine is considered to be safe for the children older than 2 years.[28]

Alternative medicine

editRoutine supplementation with vitamin C is not justified, as it does not appear to be effective in reducing the incidence of common colds in the general population.[29] The use of vitamin C in the inhibition and treatment of upper respiratory infections has been suggested since the initial isolation of vitamin C in the 1930s. Some evidence exists to indicate that it could be justified in persons exposed to brief periods of severe physical exercise and/or cold environments.[29] Given that vitamin C supplements are inexpensive and safe, people with common colds may consider trying vitamin C supplements to assess whether they are therapeutically beneficial in their case.[29]

Some low-quality evidence indicates the use of nasal irrigation with saline solution may alleviate symptoms in some people.[30] Also, saline nasal sprays can be of benefit.[citation needed]

Epidemiology

editChildren typically have two to nine viral respiratory illnesses per year.[6] In 2013, 18.8 billion cases of URTIs were reported.[31] As of 2014, they caused about 3,000 deaths, down from 4,000 in 1990.[8] In the United States, URTIs are the most common infectious illness in the general population, and are the leading reasons for people missing work and school.[citation needed]

Dietary research

editWeak evidence suggests that probiotics may be better than a placebo treatment or no treatment for preventing upper respiratory tract infections.[32]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Brown A, et al. (GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ^ Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, et al. (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ^ Guibas GV, Papadopoulos NG (2017). "Viral Upper Respiratory Tract Infections". In Green RJ (ed.). Viral Infections in Children, Volume II. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 1–25. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-54093-1_1. ISBN 978-3-319-54093-1. PMC 7121526.

- ^ Ellis ME (12 February 1998). Infectious Diseases of the Respiratory Tract. Cambridge University Press. p. 453. ISBN 978-0-521-40554-6. Archived from the original on 18 June 2024. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ a b Pokorski M (2015). Pulmonary infection. Cham: Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-17458-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Rhinitis Versus Sinusitis in Children" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 19 December 2016. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ * Heymann D (2015). Control of communicable diseases manual: an official report of the American Public Health Association. APHA Press, the American Public Health Association. ISBN 978-0-87553-018-5.

- ^ a b Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. (December 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30050819. PMC 10790329. PMID 23245604. S2CID 1541253. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ Dasaraju PV, Liu C (1996). "Chapter 93: Infections of the Respiratory System". In Baron S (ed.). Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2. PMID 21413304. Archived from the original on 26 October 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2021 – via National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Conjunctivitis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. 23 July 2020. Archived from the original on 10 July 2021. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ Bisno AL (January 2001). "Acute pharyngitis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 344 (3): 205–11. doi:10.1056/nejm200101183440308. PMID 11172144.

- ^ "Human papillomavirus (HPV) and Oropharyngeal Cancer, Sexually Transmitted Diseases". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 4 November 2016. Archived from the original on 16 December 2016. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ "Common Cold: Treatments and Drugs". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 12 February 2010. Retrieved 9 January 2010.

- ^ Weidner T, Schurr T (August 2003). "Effect of exercise on upper respiratory tract infection in sedentary subjects". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 37 (4): 304–6. doi:10.1136/bjsm.37.4.304. PMC 1724675. PMID 12893713.

- ^ Guppy MP, Mickan SM, Del Mar CB (February 2004). ""Drink plenty of fluids": a systematic review of evidence for this recommendation in acute respiratory infections". The BMJ. 328 (7438): 499–500. doi:10.1136/bmj.38028.627593.BE. PMC 351843. PMID 14988184.

- ^ a b c d Reveiz L, Cardona AF (May 2015). "Antibiotics for acute laryngitis in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (5): CD004783. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004783.pub5. PMC 6486127. PMID 26002823.

- ^ Tonkin-Crine SK, Tan PS, van Hecke O, Wang K, Roberts NW, McCullough A, et al. (September 2017). "Clinician-targeted interventions to influence antibiotic prescribing behaviour for acute respiratory infections in primary care: an overview of systematic reviews". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (9): CD012252. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012252.pub2. PMC 6483738. PMID 28881002.

- ^ Gerber JS, Ross RK, Bryan M, Localio AR, Szymczak JE, Wasserman R, et al. (December 2017). "Association of Broad- vs Narrow-Spectrum Antibiotics With Treatment Failure, Adverse Events, and Quality of Life in Children With Acute Respiratory Tract Infections". JAMA. 318 (23): 2325–2336. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.18715. PMC 5820700. PMID 29260224.

- ^ a b Spurling GK, Dooley L, Clark J, Askew DA (October 2023). "Immediate versus delayed versus no antibiotics for respiratory infections". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2023 (10): CD004417. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004417.pub6. PMC 10548498. PMID 37791590.

- ^ Little P, Francis NA, Stuart B, O'Reilly G, Thompson N, Becque T, et al. (June 2023). "Antibiotics for lower respiratory tract infection in children presenting in primary care: ARTIC-PC RCT". Health Technology Assessment. 27 (9): 1–90. doi:10.3310/DGBV3199. PMC 10350739. PMID 37436003.

- ^ "Antibiotics make little difference to children's chest infections". NIHR Evidence. UK: National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). 27 November 2023. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_60506. Archived from the original on 18 June 2024. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ Smith SM, Schroeder K, Fahey T (November 2014). "Over-the-counter (OTC) medications for acute cough in children and adults in community settings". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (11): CD001831. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001831.pub5. PMC 7061814. PMID 25420096.

- ^ Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. "Special Features – Use Caution When Giving Cough and Cold Products to Kids". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 12 January 2017. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ^ Goldsobel AB, Chipps BE (March 2010). "Cough in the pediatric population". The Journal of Pediatrics. 156 (3): 352–8. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.12.004. PMID 20176183.

- ^ "Mortality and Burden of Disease Estimates for WHO Member States in 2002" (xls). World Health Organization. 2002. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013.

- ^ Tietze KJ (2004). "Disorders related to cold and allergy". In Berardi RR (ed.). Handbook of Nonprescription Drugs (14th ed.). Washington, DC: American Pharmacists Association. pp. 239–269. ISBN 978-1-58212-050-8. OCLC 56446842.

- ^ Covington TR, ed. (2002). "Common cold". Nonprescription Drug Therapy: Guiding Patient Self-care (1st ed.). St Louis, MO: Facts & Comparisons. pp. 743–769. ISBN 978-1-57439-146-6. OCLC 52895543.

- ^ a b Chalumeau M, Duijvestijn YC (May 2013). "Acetylcysteine and carbocysteine for acute upper and lower respiratory tract infections in paediatric patients without chronic broncho-pulmonary disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD003124. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003124.pub4. PMC 11285305. PMID 23728642.

- ^ a b c Hemilä H, Chalker E (January 2013). "Vitamin C for preventing and treating the common cold". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 (1): CD000980. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000980.pub4. PMC 1160577. PMID 23440782.

- ^ King D, Mitchell B, Williams CP, Spurling GK (April 2015). "Saline nasal irrigation for acute upper respiratory tract infections" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (4): CD006821. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006821.pub3. PMC 9475221. PMID 25892369. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- ^ Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators (August 2015). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 386 (9995): 743–800. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60692-4. PMC 4561509. PMID 26063472.

- ^ Zhao Y, Dong BR, Hao Q (August 2022). "Probiotics for preventing acute upper respiratory tract infections". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022 (8): CD006895. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006895.pub4. PMC 9400717. PMID 36001877.

External links

edit- Upper Respiratory Tract Infection from Cleveland Clinic Online Medical Reference