The common redshank or simply redshank (Tringa totanus) is a Eurasian wader in the large family Scolopacidae.

| Common redshank | |

|---|---|

| |

| Breeding plumage | |

| |

| Non-breeding (winter) plumage | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Scolopacidae |

| Genus: | Tringa |

| Species: | T. totanus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Tringa totanus | |

| |

| Range of the common redshank Breeding Resident Passage Non-breeding

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Taxonomy

editThe common redshank was formally described by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in 1758 in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae under the binomial name Scolopax totanus.[2] It is now placed with twelve other species in the genus Tringa that Linnaeus had introduced in 1758.[3][4] The genus name Tringa is the Neo-Latin name given to the green sandpiper by the Italian naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi in 1603 based on Ancient Greek trungas, a thrush-sized, white-rumped, tail-bobbing wading bird mentioned by Aristotle. The specific totanus is from Tótano, the Italian name for this bird.[5]

Six subspecies are recognised:[4]

- T. t. robusta (Schiøler, 1919)[6] – breeds in Iceland and the Faroe Islands; non-breeding around the British Isles and west Europe

- T. t. totanus (Linnaeus, 1758) – breeds in west, north Europe to west Siberia; winters in Africa, India and Indonesia

- T. t. ussuriensis Buturlin, 1934[7] – breeds in southern Siberia, Mongolia and east Asia; non-breeding in Africa, India and southeast Asia

- T. t. terrignotae Meinertzhagen, R. & Meinertzhagen, A., 1926 – breeds in southern Manchuria and eastern China; non-breeding in east and southeast Asia

- T. t. craggi Hale, 1971 – breeds in northwest China; non-breeding in east and southeast Asia

- T. t. eurhina (Oberholser, 1900)[8] – breeds in Tajikistan, north India and Tibet;[9] non-breeding in India and the Malay Peninsula

Description

editCommon redshanks in breeding plumage are a marbled brown color, slightly lighter below. In winter plumage they become somewhat lighter-toned and less patterned, being rather plain greyish-brown above and whitish below. They have red legs and a black-tipped red bill, and show white up the back and on the wings in flight.

The spotted redshank (T. erythropus), which breeds in the Arctic, has a longer bill and legs; it is almost entirely black in breeding plumage and very pale in winter. It is not a particularly close relative of the common redshank, but rather belongs to a high-latitude lineage of largish shanks. T. totanus on the other hand is closely related to the marsh sandpiper (T. stagnatilis), and closer still to the small wood sandpiper (T. glareola). The ancestors of the latter and the common redshank seem to have diverged around the Miocene-Pliocene boundary, about 5–6 million years ago. These three subarctic- to temperate-region species form a group of smallish shanks with have red or yellowish legs, and in breeding plumage are generally a subdued light brown above with some darker mottling, and have somewhat diffuse small brownish spots on the breast and neck.[10]

Distribution and habitat

editThe common redshank is a widespread breeding bird across temperate Eurasia. It is a migratory species, wintering on coasts around the Mediterranean, on the Atlantic coast of Europe from Ireland and Great Britain southwards, and in South Asia. They are uncommon vagrants outside these areas; on Palau in Micronesia for example, the species was recorded in the mid-1970s and in 2000.[11] A tagged redshank was spotted at Manakudi Bird Sanctuary, Kanniyakumari District of Tamil Nadu, India in the month of April 2021.[12]

Behaviour and ecology

editThey are wary and noisy birds which will alert everything else with their loud piping call.

Breeding

editRedshanks will nest in any wetland, from damp meadows to saltmarsh, often at high densities.[13] They lay 3–5 eggs.

Food and feeding

editLike most waders, they feed on small invertebrates.

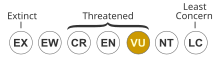

Status

editThe common redshank is widely distributed and quite plentiful in some regions, and thus not considered a threatened species by the IUCN.[1] It is one of the species to which the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA) applies.[14]

Gallery

edit-

Bird (non-breeding) in flight (Venetian Lagoon, Italy)

-

Common redshank in the Hailuoto Island, Finland

-

Common redshank is significantly smaller than, for example the Common greenshank

-

Redshank searching for food

References

edit- ^ a b c BirdLife International (2016). "Tringa totanus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22693211A86687799. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22693211A86687799.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 145.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 148.

- ^ a b Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (July 2021). "Sandpipers, snipes, coursers". IOC World Bird List Version 11.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 388, 390. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ Schiøler, E.L. (1919). "Om den Islandske Redben (Totunus calidris robustus)". Dansk Ornitologisk Forenings Tidsskrift (in Danish). XIII: 207–211.

- ^ Buturlin, S.A. (1934). Полный определитель птиц СССР [Polnyi Opredelitel Ptitsy SSSR] [Complete keys to the birds of the USSR] (in Russian). I: 88.

- ^ Oberholser, H.C. (1900). "Birds from Central Asia". Proceedings of the U.S. National Museum. XXII: 207–208.

- ^ Hale, W.G. (1971). "A revision of the taxonomy of the Redshank Tringa totanus". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 50 (3): 199–268. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1971.tb00761.x.

- ^ Pereira, Sérgio Luiz; Baker, Alan J. (2005). "Multiple Gene Evidence for Parallel Evolution and Retention of Ancestral Morphological States in the Shanks (Charadriiformes: Scolopacidae)". The Condor. 107 (3): 514–526. doi:10.1650/0010-5422(2005)107[0514:MGEFPE]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 86221767.

- ^ Wiles, Gary J.; Johnson, Nathan C.; de Cruz, Justine B.; Dutson, Guy; Camacho, Vicente A.; Kepler, Angela Kay; Vice, Daniel S.; Garrett, Kimball L.; Kessler, Curt C.; Pratt, H. Douglas (2004). "New and Noteworthy Bird Records for Micronesia, 1986–2003". Micronesica. 37 (1): 69–96. Archived from the original on 5 May 2009.

- ^ Two Tagged migratory birds spotted in salt pans in Manakudy bird reserve, The Hindu, Thiruchirappalli, Tamil Nadu Edition, India, pp4, 12.04.2021. thehindu.com

- ^ Cadbury, C. J.; Green, R.; Allport, G. (1987). "Redshanks and other breeding waders of British saltmarshes". RSPB Conservation Review. Vol. 1. pp. 37–40 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ "Species". Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA). Retrieved 14 November 2021.

External links

edit- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Redshank Images and documentation

- Ageing and sexing (PDF; 1.4 MB) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze

- "Tringa totanus". Avibase.

- "Common redshank media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Common redshank photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Interactive range map of Tringa totanus at IUCN Red List maps

- Audio recordings of Common redshank on Xeno-canto.

- Tringa totanus in Field Guide: Birds of the World on Flickr

- Common redshank media from ARKive