The banded houndshark (Triakis scyllium) is a species of houndshark in the family Triakidae, common in the northwestern Pacific Ocean from the southern Russian Far East to Taiwan. Found on or near the bottom, it favors shallow coastal habitats with sandy or vegetated bottoms, and also enters brackish water. This shark reaches 1.5 m (4.9 ft) in length. It has a short, rounded snout and mostly narrow fins; the pectoral fins are broad and triangular, and the trailing margin of the first dorsal fin is almost vertical. It is gray above and lighter below; younger sharks have darker saddles and dots, which fade with age.

| Banded houndshark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Order: | Carcharhiniformes |

| Family: | Triakidae |

| Genus: | Triakis |

| Species: | T. scyllium

|

| Binomial name | |

| Triakis scyllium J. P. Müller & Henle, 1839

| |

| |

| Range of the banded houndshark[2] | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Hemigaleus pingi Evermann & Shaw, 1927 | |

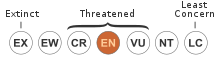

Nocturnal and largely solitary, the banded houndshark preys on benthic invertebrates and bony fishes. It is aplacental viviparous, with the developing embryos sustained by yolk. After mating during summer, females bear as many as 42 pups following a gestation period of 9–12 months. The banded houndshark poses no danger to humans and adapts well to captivity. It is caught as bycatch off Japan, Taiwan, and likely elsewhere in its range; it may be eaten but is not as well-regarded as related species. Because fishing does not appear to have diminished this shark's population, the International Union for Conservation of Nature has listed it under Endangered.

Taxonomy

editThe first scientific description of the banded houndshark was authored by German biologists Johannes Peter Müller and Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle, based on a dried specimen from Japan, in their 1838–41 Systematische Beschreibung der Plagiostomen. They gave it the specific epithet scyllium, derived from the Ancient Greek skylion ("dogfish"), and placed it in the genus Triakis.[3] Within the genus, it is placed in the subgenus Triakis along with the leopard shark (T. (Triakis) semifasciata).[2]

Distribution and habitat

editNative to the northwestern Pacific Ocean, the banded houndshark occurs from the southern Russian Far East to Taiwan, including Japan, Korea, and eastern China; records from the Philippines are questionable.[1] This common, benthic shark is found over continental and insular shelves, mostly close to shore, but also to a depth of 150 m (490 ft).[4] It frequents sandy flats and beds of seaweed and eelgrass; additionally, it is tolerant of brackish water and enters estuaries and bays.[1]

Description

editThe banded houndshark is a moderately slender-bodied species growing up to 1.5 m (4.9 ft) long. The snout is short, broad, and rounded; the widely separated nostrils are each preceded by a lobe of skin that does not reach the mouth. The horizontally oval eyes are placed high on the head; they are equipped with rudimentary nictitating membranes (protective third eyelids) and have prominent ridges underneath. The mouth forms a short, wide arch and bears long furrows at the corners that extend onto both jaws. Each tooth has an upright to oblique knife-like central cusp flanked by strong cusplets. There are five pairs of gill slits.[2]

Most of the fins are fairly narrow; in adults the pectoral fins are broad and roughly triangular. The moderately tall first dorsal fin is placed about halfway between the pectoral and pelvic fins, and its trailing margin is nearly vertical near the apex. The second dorsal fin is about three-quarters as high as the first and larger than the anal fin. The caudal fin has a well-developed lower lobe and a prominent ventral notch near the tip of the upper lobe; in young sharks the lower caudal fin lobe is much less distinct.[2] This species is gray above, with darker saddles and scattered black spots that fade with age; the underside is off-white.[4]

Biology and ecology

editThe banded houndshark is nocturnal and generally solitary, though several individuals may rest together, sometimes piled atop one another inside a cave.[4][5] It feeds mainly on crustaceans (including shrimp, crabs, hermit crabs, and mantis shrimp), cephalopods (including octopus), and spoon worms; polychaete worms, tunicates, peanut worms, and small, bottom-living bony fishes (including flatfishes, conger eels, herring, jacks, drums, and grunts) are occasionally consumed. Shrimp and spoon worms are important prey for sharks up to 70 cm (28 in) long; cephalopods predominate in the diets of larger sharks.[6]

Mating occurs during the summer, and involves the male swimming parallel to the female and gripping her pectoral fin with his teeth; thus secured, he then twists the distal portion of his body to insert a single clasper into her cloaca for copulation. The banded houndshark is aplacental viviparous, in which the developing embryos are sustained to birth by yolk. Females bear litters of 9–26 pups after a gestation period of 9–12 months, though litters as large as 42 pups have been recorded.[5][7][8]

In 2016, at the Uozu Aquarium in Japan, two puppies were born in a tank with only females, and parthenogenesis was confirmed.[9]

The newborns measure 18–20 cm (7.1–7.9 in) long. Males mature sexually at 5–6 years old, when they are 93–106 cm (37–42 in) long, and live up to 15 years. Females mature sexually at 6–7 years old, when they are 106–107 cm (42–42 in) long, and live up to 18 years.[1] Known parasites of this species include the tapeworms Callitetrarhynchus gracilis,[10] Onchobothrium triacis, and Phyllobothrium serratum,[11] the leech Stibarobdella macrothela,[12] and the copepods Achtheinus impenderus,[13] Caligus punctatus,[14] Kroyeria triakos,[15] and Pseudopandarus scyllii.[16]

Human interactions

editHarmless to humans,[17] the banded houndshark is commonly displayed in public aquariums in China and Japan,[1] and has reproduced in captivity.[8] Individuals have survived in captivity for over five years.[5] This species is often caught incidentally off Japan in gillnets and set nets; the meat is sometimes sold, but is considered to be of poorer quality than that of other houndsharks in the region. It is caught in lesser numbers off Taiwan, and is probably also fished off Korea and northern China. Off Japan, it can be found in rocky areas that provide refuge from fishing pressure.[1]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f Rigby, C.L.; Walls, R.H.L.; Derrick, D.; Dyldin, Y.V.; Herman, K.; Ishihara, H.; Jeong, C.-H.; Semba, Y.; Tanaka, S.; Volvenko, I.V.; Yamaguchi, A. (2021). "Triakis scyllium". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T161395A124476903. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-1.RLTS.T161395A124476903.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d Compagno, L.J.V. (1984). Sharks of the World: An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Shark Species Known to Date. Rome: Food and Agricultural Organization. p. 432. ISBN 92-5-101384-5.

- ^ Müller, J. & F.G.J. Henle (1838–41). Systematische Beschreibung der Plagiostomen. Veit und Comp. pp. 63–64.

- ^ a b c Hennemann, R.M. (2001). Sharks & Rays: Elasmobranch Guide of the World (second ed.). IKAN – Unterwasserarchiv. p. 113. ISBN 3-925919-33-3.

- ^ a b c Michael, S.W. (1993). Reef Sharks & Rays of the World. Sea Challengers. p. 59. ISBN 0-930118-18-9.

- ^ Kamura, S.; Hashimoto, H. (2004). "The food habits of four species of triakid sharks, Triakis scyllium, Hemitriakis japanica, Mustelus griseus and Mustelus manazo, in the central Seto Inland Sea, Japan". Fisheries Science. 70 (6): 1019–1035. Bibcode:2004FisSc..70.1019K. doi:10.1111/j.1444-2906.2004.00902.x.

- ^ Ni, J.; Li, J.; Xu, Y. (1992). "Preliminary observation on the feeding habits and reproduction of Triakis scyllium". Journal of Oceanography of Huanghai & Bohai Seas. 10 (1): 42–46. Archived from the original on 2013-06-09. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

- ^ a b Michael, S.W. (2001). Aquarium Sharks & Rays. T.F.H. Publications. p. 229. ISBN 1-890087-57-2.

- ^ "メスしか泳いでないのになぜ? 赤ちゃんザメ誕生 富山". 朝日新聞. 2016-08-25. Archived from the original on September 14, 2016.

- ^ Williams, H.H.; Jones, A. (1994). Parasitic Worms of Fish. CRC Press. p. 390. ISBN 0-85066-425-X.

- ^ Yamaguti, S. (1952). "Studies on the helminth fauna of Japan. Part 49. Cestodes of fishes, II". Acta Medicinae Okayama. 8: 1–76. Archived from the original on 2011-08-23. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

- ^ Yamauchi, T.; Ota, Y.; Nagasawa, K. (August 20, 2008). "Stibarobdella macrothela (Annelida, Hirudinida, Piscicolidae) from Elasmobranchs in Japanese Waters, with New Host Records". Biogeography. 10: 53–57.

- ^ Shen, C.J.; Wang, K.N. (1959). "A new parasitic copepod, Achtheinus impenderus (Coligoida, Pandaridae), from a shark taken at Peitaiho, Hopei Province". Acta Zoologica Sinica. 10 (1): 27–31.

- ^ Boxshall, G.A.; Defaye, D., eds. (1993). Pathogens of Wild and Farmed Fish: Sea Lice. CRC Press. p. 16. ISBN 0-13-015504-7.

- ^ Izawa, K. (2008). "Redescription of four species of Kroyeria and Kroeyerina (Copepoda, Siphonostomatoida, Kroyeriidae) infecting Japanese sharks". Crustaceana. 81 (6): 695–724. doi:10.1163/156854008784513465.

- ^ Yamaguti, S.; Yamasu, T. (1959). "Parasitic copepods from fishes of Japan with descriptions of 26 new species and remarks on two known species". Biological Journal of Okayama University. 5 (3/4): 89–165.

- ^ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Triakis scyllium". FishBase. May 2011 version.