This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (March 2017) |

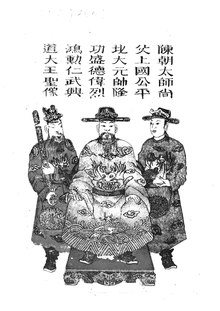

Trần Hưng Đạo (Vietnamese: [ʈə̂n hɨŋ ɗâːwˀ]; 1228–1300), real name Trần Quốc Tuấn (陳國峻), also known as Grand Prince Hưng Đạo (Hưng Đạo Đại Vương – 興道大王), was a Vietnamese royal prince, statesman and military commander of Đại Việt military forces during the Trần dynasty. After his death, he was considered a saint and deified by the people and named Đức Thánh Trần (德聖陳) or Cửu Thiên Vũ Đế (九天武帝).[1][2] Hưng Đạo commanded the Vietnamese armies that repelled two out of three major Mongol invasions in the late 13th century.[3] His multiple victories over the Yuan dynasty under Kublai Khan are considered among the greatest military feats in Vietnamese history.

| Trần Hưng Đạo | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imperial Prince of Đại Việt Grand Prince of Hưng Đạo | |||||

| |||||

| Born | 1228 Tức Mặc, Mỹ Lộc, Thiên Trường, Đại Việt (today Nam Định, Vietnam) | ||||

| Died | 1300 (aged 71–72) Vạn Kiếp, Đại Việt (today Chí Linh, Hải Dương Province, Vietnam) | ||||

| Burial | An Lạc garden | ||||

| Spouse | Mother of the Nation Lady Nguyên Từ | ||||

| Issue | Trần Thị Trinh Trần Quốc Nghiễn Trần Quốc Hiện Trần Quốc Tảng | ||||

| |||||

| House | Trần dynasty | ||||

| Father | Prince Trần Liễu | ||||

| Mother | Mother of the Nation Lady Thiện Đạo | ||||

| Religion | Buddhism | ||||

| Occupation | Quốc công tiết chế thống lĩnh chư quân (Commander-in-chief of the armies) | ||||

Origins

editTrần Hưng Đạo was born as Prince Trần Quốc Tuấn (陳 國 峻) in 1228, as a son of Prince Trần Liễu, the elder brother of the new child emperor, Trần Thái Tông, after the Trần dynasty replaced the Lý family in 1225 AD. Later, Trần Liễu—the Empress Lý Chiêu Hoàng's brother-in-law at the time—was forced to defer his own wife (Princess Thuận Thiên) to his younger brother Emperor Thái Tông under pressure from Imperial Regent Trần Thủ Độ to solidify Trần clan's dynastic stability. The brothers Trần Liễu and Emperor Trần Thái Tông harboured grudges against their uncle Trần Thủ Độ for the forced marital arrangement.

First Mongol invasion

edit| Trần Hưng Đạo | |

| Vietnamese alphabet | Trần Hưng Đạo |

|---|---|

| Chữ Hán | 陳興道 |

During the first Mongol invasion of Vietnam in 1258, Trần Hưng Đạo served as an officer commanding troops on the frontier.[citation needed]

Second Mongol invasion

editIn 1278, Trần Thái Tông died. King Trần Thánh Tông retired and made crown prince Trần Khâm (known as Trần Nhân Tông, and to the Mongol as Trần Nhật Tôn) his successor. Kublai sent a mission led by Chai Chun to Đại Việt, and once again urged the new king to come to China in person, but the king refused.[4]: 212 The Yuan then refused to recognize him as king, and tried to place a Vietnamese defector as king of Đại Việt.[5]: 105 Frustrated with the failed diplomatic missions, many Yuan officials urged Kublai to send a punitive expedition to Đại Việt.[4]: 213 In 1283, Khublai Khan sent Ariq Qaya to Đại Việt with an imperial request for Đại Việt to help attack Champa through Vietnamese territory, and demands for provisions and other support for the Yuan army, but the king refused.[6]: 213 [7]: 19

In January 1285, Prince Toghan led the Mongol invasion of Đại Việt.[8] Trần Hưng Đạo was the general of the combined Đại Việt land and naval forces, which was routed by the main Mongol land forces and retreated back to the capital Thăng Long.[8] After hearing about the successive defeats, emperor Trần Nhân Tông travelled by small boat to meet Trần Hưng Đạo in Quảng Ninh and ask him if Đại Việt should surrender.[8] Trần Hưng Đạo resisted and asked for the aid of the private armies of the Trần princes.[8] In early 1285, Trần envoys offered peace terms to the Mongols.[8] Toghan and his deputy Omar Batur refused, engaged Trần Hưng Đạo's forces in battle on the banks of the Red River, and successfully captured Thăng Long.[8] Trần Hưng Đạo escorted the Trần royalty to their palace at Thiên Trường in Nam Định.[8]

The Mongol forces under Sodu, deputy to Toghan, continued to push further south and installed defected prince Trần Ích Tắc as the new King of Annam.[8] The Trần forces had their forces surrounded by the Yuan army while their emperors fled along the coast to Thanh Hóa.[8] As fighting in Champa intensified, Toghan ordered Sodu to return to Champa with the warm weather and disease in Đại Việt given as the official reason.[8] During this retreat, Trần Hưng Đạo's forces inflicted major victories over on the Red River, resulting in the death of Sodu and the retreat of Omar Batur to China.[8] Đại Việt forces retook Thăng Long and Toghan returned to China with great losses.[8]

Third Mongol invasion

editIn 1287, Kublai Khan this time sent one of his favorite sons, Prince Toghan to lead another invasion campaign into Đại Việt with a determination to occupy and redeem the previous defeat. The Yuan Mongol and Chinese forces formed an even larger infantry, cavalry and naval fleet with the total strength estimated at 120,000 troops according to the Mongols and 500,000 men according to the Vietnamese.

During the first stage of the invasion, the Mongols quickly defeated most of the Đại Việt troops that were stationed along the border. Prince Toghan's naval fleet devastated most of the naval force of General Trần Khánh Dư in Vân Đồn. Simultaneously, Prince Ariq-Qaya led his massive cavalry and captured Phú Lương and Đại Than garrisons, two strategic military posts bordering Đại Việt and China. The cavalry later rendezvous with Prince Toghan's navy in Vân Đồn. In response to the battle skirmish defeats at the hands of the Mongol forces, the Emperor Emeritus Trần Thánh Tông summoned General Trần Khánh Dư to be court-martialed for military failures, but the general managed to delay reporting to the court and was able to regroup his forces in Vân Đồn. The cavalry and fleet of Prince Toghan continued to advance into the imperial capital Thăng Long. Meanwhile, the trailing supply fleet of Prince Toghan, arriving at Vân Đồn a few days after General Trần Khánh Dư's had already occupied this strategic garrison, the Mongol supply fleet was ambushed and captured by General Trần Khánh Dư's forces. Khánh Dư was then pardoned by Emperor Emeritus. The Mongol main occupying army quickly realized their support and supply fleet has been cut off.

The capture of the Mongol supply fleet at Vân Đồn along with the concurring news that General Trần Hưng Đạo had recaptured Đại Than garrison in the north sent the fast advancing Mongol forces into chaos. The Đại Việt forces unleashed guerrilla warfare on the weakened Mongol forces causing heavy casualties and destructions to the Yuan forces. However, the Mongols continued advancing into Thăng Long due to their massive cavalry strength, but by this time, the emperor decided to vacate Thăng Long to flee and he ordered the capital to be burned down so the Mongols wouldn't collect any spoils of war. The subsequent battle skirmishes between the Mongols and Đại Việt had mixed results: the Mongols won and captured Yên Hưng and Long Hưng provinces, but lost in the naval battles at Đại Bàng. Eventually, Prince Toghan decided to withdraw his naval fleet and consolidate his command on land battles where he felt the Mongol's superior cavalry would defeat the Đại Việt infantry and cavalry forces. Toghan led the cavalry through Nội Bàng while his naval fleet commander, Omar, directly launched the naval force along the Bạch Đằng River simultaneously.

The Battle of Bạch Đằng River

editThe Mongol naval fleet was unaware of the river's terrain. Days before this expedition, the Prince of Hưng Đạo predicted the Mongol's naval route and quickly deployed heavy unconventional traps of steel-tipped wooden stakes unseen during high tides along the Bạch Đằng River bed. When Omar ordered the Mongol fleet to retreat from the river, the Viet deployed smaller and more maneuverable vessels into agitating and luring the Mongol vessels into the riverside where the booby traps were waiting while it was still high tide. As the river tide on Bạch Đằng River receded, the Mongol vessels were stuck and sunk by the embedded steel-tipped stakes. Under the presence of the Emperor Emeritus Thánh Tông and Emperor Nhân Tông, the Viet forces led by the Prince of Hưng Đạo burned down an estimated 400 large Mongol vessels and captured the remaining naval crew along the river. The entire Mongol fleet was destroyed and the Mongol fleet admiral Omar was captured.[9]

The cavalry force of Prince Toghan was more fortunate. They were ambushed by General Phạm Ngũ Lão along the road through Nội Bàng, but his remaining force managed to escape back to China by dividing their forces into smaller retreating groups but most were captured or killed in skirmishes on the way back to the border frontier, resulting in losing half the remaining army.

Death

editIn 1300 AD, he fell ill and died of natural causes at the age of 73. His body was cremated and his ashes were dispersed under his favorite oak tree he planted in his royal family estate near Thăng Long in accordance to his will. The Viet intended to bury him in a lavish royal mausoleum and official ceremony upon his death, but he declined in favour of a simplistic private ceremony. For his military brilliance in defending Đại Việt during his lifetime, the Emperor posthumously bestowed Trần Hưng Đạo the title of Hưng Đạo Đại Vương (Grand Prince Hưng Đạo).

Family

edit- Father: Prince Yên Sinh

- Mother: Lady Thiện Đạo

- Consort: Princess Thiên Thành

- Issues:

- Trần Quốc Nghiễn, later Prince Hưng Vũ

- Trần Quốc Hiện, later Prince Hưng Trí

- Trần Quốc Tảng, later Prince Hưng Nhượng, father of Empress Consort Bảo Từ of Emperor Trần Anh Tông

- Trần Quốc Uy, later Prince Hưng Hiếu

- Trần Thị Trinh, later Empress Consort Khâm Từ Bảo Thánh of Emperor Trần Nhân Tông

- Empress Tuyên Từ

- Princess Anh Nguyên, later wife of General Phạm Ngũ Lão

Legacy

editPlacenames

editThe majority of cities and towns in Vietnam have central streets, wards and schools named after him.[10][11][12]

- Hanoi's Tran Hung Dao street (previously Boulevard Gambetta during the French Indochina time) is a major road in the south of Hoan Kiem District. It links the city's First Ring Road (originally Route Circulaire) to the main hall of the Central Station. Several embassies and government ministries are located on this street.

- Hai Phong's Tran Hung Dao road runs along the central park square and links the Haiphong Opera House and the Cấm River.

- Da Nang's Tran Hung Dao road is a waterfront boulevard on the eastern side of the Hàn River.

- Ho Chi Minh City's Tran Hung Dao road is a thoroughfare of its Chinatown. It also hosts the headquarters of the city police and fire departments. A statue in honor of him is placed at a major square at city downtown.

- A statue in Westminster, CA is dedicated to him, with the road Bolsa Avenue given an alternative name "Đại Lộ Trần Hưng Đạo", translating to "Trần Hưng Đạo Boulevard".

Shrines

editHe is revered by the Vietnamese people as a national hero. Several shrines are dedicated to him, and even religious belief and mediumship includes belief in him as a god, Đức Thánh Trần (Tín ngưỡng Đức Thánh Trần).

Other

editThe Tran Hung Dao a Gepard-class frigate commissioned in 2018 for the Vietnam People's Navy is named after him.

See also

edit- Hịch tướng sĩ Proclamation to the Officers

- History of Vietnam

- Mongol invasions of Vietnam

- Trần dynasty military tactics and organization

References

edit- ^ Marie-Carine Lall, Edward Vickers Education As a Political Tool in Asia 2009. p. 144 "... to the official national autobiography, the legends relating to the origins of the nation are complemented by other legends of heroes in order to constitute the Vietnamese nation's pantheon: Hai Bà Trưng, Lý Thường Kiệt, Trần Hưng Đạo, etc."

- ^ Bruce M. Lockhart, William J. Duiker The A to Z of Vietnam p. 374 Trần Hưng Đạo

- ^ "Vietnam - The Tran Dynasty and the Defeat of the Mongols". countrystudies.us.

- ^ a b Sun, Laichen (2014). "Imperial Ideal Compromised: Northern and Southern Courts Across the New Frontier in the Early Yuan Era". In Anderson, James A.; Whitmore, John K. (eds.). China's Encounters on the South and Southwest: Reforging the Fiery Frontier Over Two Millennia. United States: Brill. pp. 193–231.

- ^ Haw, Stephen G. (2006). Marco Polo's China: A Venetian in the Realm of Khubilai Khan. Taylor & Francis.

- ^ Anderson, James A. (2014). "Man and Mongols: the Dali and Đại Việt Kingdoms in the Face of the Northern Invasions". In Anderson, James A.; Whitmore, John K. (eds.). China's Encounters on the South and Southwest: Reforging the Fiery Frontier Over Two Millennia. United States: Brill. pp. 106–134. ISBN 978-9-004-28248-3.

- ^ Baldanza, Kathlene (2016). Ming China and Vietnam: Negotiating Borders in Early Modern Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-53131-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Lien, Vu Hong; Sharrock, Peter (2014). "6: The Trần Dynasty (1226-1443)". Descending Dragon, Rising Tiger: A History of Vietnam. Reaktion Books. ISBN 9781780233888.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên (1993), Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư (in Vietnamese) (Nội các quan bản ed.), Hanoi: Social Science Publishing House, pp. 196–198

- ^ Vietnam Country Map. Periplus Travel Maps. 2002–2003. ISBN 0-7946-0070-0.

- ^ Andrea Lauser, Kirsten W. Endres Engaging the Spirit World: Popular Beliefs and Practices in Modern Vietnam p. 94 2012 "These scholars may have underestimated existing links between male and female rituals. Nowadays, as Phạm Quỳnh Phương (2009) has noted, a strict distinction between the Mothers' cult and the cult of Trần Hưng Đạo is no longer upheld, "

- ^ Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David: Vietnam Past and Present: The North (History and culture of Hanoi and Tonkin). Chiang Mai. Cognoscenti Books, 2012. ASIN: B006DCCM9Q.

Bibliography

edit- Taylor, K. W. (2013). A History of the Vietnamese (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521875862. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- Hall, Kenneth R., ed. (2008). Secondary Cities and Urban Networking in the Indian Ocean Realm, C. 1400–1800. Volume 1 of Comparative urban studies. Lexington Books. ISBN 0739128353. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

External links

edit- Tran Hung Dao (1213–1300)

- Statue of Trần Hưng Đạo, Vietnamese Hero, 19th–20th. C.

- (in French) Le Vietnam et la stratégie du faible au fort

- Call of Soldiers Translated and adapted by George F. Schultz