Tonquin was a 290-ton American merchant ship initially operated by Fanning & Coles and later by the Pacific Fur Company (PFC), a subsidiary of the American Fur Company (AFC). Its first commander was Edmund Fanning, who sailed to the Qing Empire for valuable Chinese trade goods in 1807. The vessel was outfitted for another journey to China and then was sold to German-American entrepreneur John Jacob Astor. Included within his intricate plans to assume control over portions of the lucrative North American fur trade, the ship was intended to establish and supply trading outposts on the Pacific Northwest coast. Valuable animal furs purchased and trapped in the region would then be shipped to China, where consumer demand was high for particular pelts.

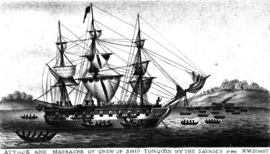

Tonquin being boarded by Tla-o-qui-aht

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Owner | Edmund Fanning |

| Operator | Edmund Fanning |

| Builder | Adam and Noah Brown |

| Laid down | 1 March 1807[1] |

| Launched | 26 May 1807[1] |

| Acquired | 1807 |

| Fate | Sold to the Pacific Fur Company |

| Owner | John Jacob Astor |

| Operator | Jonathan Thorn |

| Acquired | 23 August 1810 |

| Fate | Blown up 16 June 1811 at Clayoquot Sound, Vancouver Island |

| Sunk | 1811 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Bark |

| Tons burthen | 269 or 290 bm[2] |

| Length | 96 ft (29 m) |

| Propulsion | Sail, three-masted |

| Armament | 10 guns, fitted for 22[1] |

Tonquin began its journey to the Columbia River in late 1810, departing New York City and heading south through the Atlantic Ocean. In December, it reached the Falkland Islands, where Captain Jonathan Thorn briefly marooned eight PFC employees.[3][4] After passing Cape Horn into the Pacific Ocean, Tonquin visited the Kingdom of Hawaii in February 1811, where the ship restocked and hired 24 Native Hawaiian Kanakas after negotiations with Kamehameha I and Kalanimoku. Tonquin finally reached the Columbia River on 22 March 1811. Eight crewmen died before the ship found a safe route over the Columbia Bar.

Work began in May 1811 on the sole trading post founded by Tonquin, Fort Astoria, on the present-day Oregon coast. After construction was completed, the ship departed with a majority of the trade goods and general provisions from the fort, intending to trade them with indigenous tribes on the coast of Vancouver Island. When the crew began bartering with Tla-o-qui-aht natives at Clayoquot Sound in June, a dispute arose due to Captain Thorn's poor treatment of an elder.[5] All but four members of the crew were killed by armed Tla-o-qui-aht led by chief Wickaninnish. The survivors intentionally detonated the ship's powder magazine, and Tonquin was destroyed and sunk. Joseachal, a Quinault interpreter previously hired by Thorn, was the sole crew member to survive the entire incident and return to Fort Astoria. While there, he held several conversations with Duncan McDougall and gave the only detailed account of how Tonquin was destroyed.

Fanning & Coles

editConstruction

editTonquin was constructed by Adam and Noah Brown at a dry dock in New York City in 1807.[1]

Maiden voyage

editTonquin was first purchased by Fanning & Coles to participate in the Old China Trade. It originally had a crew of 24, including its captain, Edmund Fanning.[6] She departed New York City harbor on 26 May 1807 for the port of Guangzhou. Outside the port cities of China, Tonquin survived a typhoon while crossing the Macclesfield Bank.[7] From there the vessel passed the Wanshan Archipelago on its way to Guangzhou. Prior to returning to the United States, Tonquin was detained by Commodore Edward Pellew. Apparently Fanning was previously acquainted with both Pellew and his father, and after a discussion with Pellew, Fanning subsequently was allowed to start the return voyage, leaving the port on 18 November 1807.[8]

Another vessel owned by Fanning & Coles, Hope, was encountered the same day. After meeting with its captain, Reuben Brumley, Fanning continued to sail towards the Bocca Tigris. A squadron of British vessels stationed there stopped Tonquin and detained it for a day. The following day, orders from Commodore Pellew arrived, detailing that Tonquin was to be freed immediately and sent Fanning "his apology for your detention, and his good wishes, that you may have a pleasant and safe passage."[9] Prior to the departure of the principal British officers, a toast to the United States and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was held. Fanning returned to New York City with a full cargo of valuable trade goods on 6 March 1808.[1]

Second voyage

editOrganized in 1808, the second voyage of Tonquin was focused on the active sandalwood trade throughout the Pacific Ocean. The previous year, an arrangement with a group of iTaukei people on Fiji was made by Captain Brumley of Hope. The sandalwood tree Santalum yasi was to be cut, collected, and processed by the iTaukei until Brumley returned in 18 months.[10] The then still active Embargo Act of 1807 was a potential roadblock in this overseas project. Coles and Fanning both went to Washington, D.C. to request federal approval for the voyage to Fiji. There they held meetings with Albert Gallatin, the Secretary of the Treasury. Gallatin sent the proposal to President Thomas Jefferson, who formally approved it.

Tonquin was dispatched to Fiji on 15 June 1808.[10] Brumley was appointed captain, with Coles and Fanning both on board. From New York City, the vessel went south through the Atlantic Ocean and sailed past part of the Brazilian coast and later Gough Island. After passing Cape Horn, the ship continued to sail west, landing at King George Sound in modern Western Australia on 8 October 1808. A tent there was made to allow crew members with scurvy to recover. Local Noongar groups frequently visited the Americans at their tent. Through signs the Noongar would initiate potential commercial transactions by establishing their peaceful intentions through dropping their weapons. Only after the Americans would put down their firearms would a spirited trade begin between the two groups. American goods such as beads, metal buttons and knives were often exchanged in return for Noongar-manufactured stone tools and food supplies. Those of the crew afflicted with illness were restored to health over the following days. Tonquin left the sound on 21 October for Tongatapu, where local peoples sold the crew stockpiles of "hogs, bread-fruit, [and] yams" among other products.[11]

On 10 December, Tonquin passed Vatoa and landed at Vanua Levu the following day. Greeted by a group of iTaukei men bearing gifts of fruit, the Americans informed their hosts of the previous agreement made over sandalwood. The dignitaries soon departed to transmit news elsewhere. Shortly after sunrise the next day, iTaukei men gave fresh coconuts, breadfruit, hogs, and yams from their assembled canoes. The local leader, Tynahoa, arrived with his followers and announced that he had the agreed amount of sandalwood harvested and stockpiled. Over the course of an hour the Americans and Tynahoa held a discussion on board Tonquin. He told the merchants that several British ships from Port Jackson had visited and were still anchored nearby during the time of Brumley's absence. However, he was insistent that no sandalwood had been sold to them, as he had declared a tabu on the sale of sandalwood among his subordinates.[12]

The sandalwood was delivered gradually to Tonquin from subjects of Tynahoa. This process would span several months, although the wait was apparently worth it. Fanning later stated that the entire hull and part of the deck were loaded with the raw material. The tabu was formally absolved by Tynahoa, allowing the waiting British merchants to finally purchase their own supplies of sandalwood. Tonquin departed for Guangzhou on 22 March 1809.[12] Sailing roughly northwest from Vanua Levu, the islands of modern Vanuatu and the Solomon Islands were sighted, in addition to parts of the Federated States of Micronesia, such as Kapingamarangi, which Fanning called the Equator Isles.[13] After entering the Guangzhou port, the sandalwood cargo was sold in return for various Chinese products. Tonquin safely returned to New York City.[14]

Pacific Fur Company

editTonquin was sold for $37,860 (equivalent to $738,000 in 2023) to German-American businessman John Jacob Astor on 23 August 1810.[15] Astor purchased the vessel to spearhead his plans for gaining a foothold in the ongoing maritime fur trade on the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America.[16] Tonquin was assigned to the Pacific Fur Company (PFC) to accomplish this major commercial goal. The PFC was a subsidiary venture funded largely by the American Fur Company, the original fur enterprise founded by Astor in 1808. Astor was able to gain the services of United States Navy lieutenant Jonathan Thorn and put him in command of the 10-gun merchant vessel.[16]

Atlantic Ocean

editOn 8 September 1810, Tonquin departed New York harbor bound for the Columbia River in the Pacific Northwest.[17] Cargo on board included fur trade goods, seeds, building material for a trading post, tools, and the frame of a schooner to be used in the coastal trade.[16] The crew consisted of 34 people including the captain, 30 of whom were British subjects.[18] Four partners of the company were on board: Duncan McDougall, David and Robert Stuart, and Alexander McKay.[16] Additionally there were 12 clerks and 13 Canadian voyageurs, plus four tradesmen: Augustus Roussel, a blacksmith; Johann Koaster, a carpenter; Job Aitkem, a boat builder; and George Bell, a cooper.[19]

After leaving the national waters of the United States, Tonquin sailed southeast into the Atlantic. On 5 October, the ship came within sight of Boa Vista in the Cape Verde Islands.[20] The enforced policy of impressment by the United Kingdom made Thorn wary of passing British vessels. Consequently, he decided against staying at the holdings of the Kingdom of Portugal and avoided the Cape Verde Islands.[21] After sailing down the coast of West Africa, Tonquin made way for South America. Off the coast of Argentina an extreme storm struck, ruining many of the sails and adding two additional leaks in the hull.[22] As the voyage continued on, the freshwater supplies dwindled to three gills a day per sailing member.[23]

The vessel landed at the Falkland Islands on 4 December to make repairs and take on water supplies, with a suitable source of freshwater located at Port Egmont.[24] Captain Thorn set sail on 11 December without eight of the men, including partner David Stuart, Gabriel Franchère and Alexander Ross.[3][4] Having only a rowboat, the eight men spent over six hours rowing before they caught up with Tonquin.[3][4] Robert Stuart quickly threatened Thorn to stop the ship, saying if he refused then "You are a dead man this instant."[4] This display made Thorn order the Tonquin crew to sail back and pick up the stranded crew. Thorn's actions led to increasing tensions between him and the employees of the Pacific Fur Company. Communication between company workers was no longer held in English to keep the captain excluded from discussions. Company partners held talks in their ancestral Scottish Gaelic and hired PFC workers used Canadian French. The atmosphere of "their jokes and chanting their outlandish songs" greatly frustrated Thorn.[4] On 25 December, Tonquin safely traversed around Cape Horn and sailed north into the Pacific Ocean.

Pacific Ocean

editTonquin reached the Kingdom of Hawaii on 12 February 1811, dropping anchor at Kealakekua Bay.[25] The possibility of men deserting the ship in favor of the islands became a major threat. Thorn had no choice but to make amends with the PFC partners to police the crew.[26] Several men abandoned ship but the cooperation of the nearby Native Hawaiians saw their return. One man was flogged, another put in chains. Thorn assembled all of the crew and PFC employees and harassed the men to remain on the ship.[26] Commercial transactions eventually began with the Hawaiians; the crew purchased cabbage, sugar cane, purple yams, taro, coconuts, watermelon, breadfruit, hogs, goats, two sheep,[27] and poultry for "glass beads, iron rings, needles, cotton cloth".[26][25] A courier from government agent John Young ordered Tonquin to visit him for meat supplies and then to have an audience with King Kamehameha I who resided on Oʻahu.[28][22]

Upon entering Honolulu, the crew was greeted by Francisco de Paula Marín and Isaac Davis. Marín acted as an interpreter in negotiations with Kamehameha I and Kalanimoku, a prominent Hawaiian government official.[29] Besides his work in discussion between the Hawaiian Monarch and the PFC officers, Marín also acted as the pilot to guide the ship into port, for which he received five Spanish dollars.[30] Twenty-four Hawaiian kanakas were recruited for three years service, half in the fur venture and the other half as laborers on Tonquin.[31] One of the Hawaiians, Naukane, was appointed by Kamehameha I to oversee the interests of these laborers. Naukane was given the name John Coxe while on Tonquin and later joined the North West Company.[32] Tonquin and its crew left the Hawaiian Kingdom on 1 March 1811.[33]

The Columbia River was reached on 22 March 1811, but its dangerous bar posed a major problem.[34] Thorn sent five men in a boat to attempt to locate the channel, but the rough surf capsized the vessel and its crew was lost. Two days later another attempt by an additional small boat also sank. Of the five crew members, which included two Hawaiian Kanakas, only an American and a Hawaiian survived. In total eight men died attempting to find a safe route past the Columbia Bar.[35] Finally, on March 24, Tonquin crossed into the Columbia's estuary and laid anchor in Baker Bay. The personnel then proceeded fifteen miles up the river to present-day Astoria, Oregon,[16] where they spent two months laboring to establish Fort Astoria. Some trade goods and other materials that composed the cargo were transferred to the new trading post.[36] During this work, small transactions with curious Chinookan Clatsop people occurred.

Destruction

editOn 5 June 1811, Tonquin left Baker's Bay with a crew of 24 and sailed north for Vancouver Island to trade with various Nuu-chah-nulth peoples living on the island's west coast.[16] Alexander McKay was aboard the ship as supercargo and James Lewis as clerk.[16] Near Destruction Island, a member of the Quinault nation, Joseachal, was recruited by Thorn to act as an interpreter, being recorded as "Joseachal" by McDougall in company records. He had a sister married to a Tla-o-qui-aht man, a factor that has been attributed to his later survival on Vancouver Island.[37]

While anchored at Clayoquot Sound, the Tonquin crew engaged in fur trading activities with the natives. Members of the neighboring Tla-o-qui-aht nation boarded the ship in large numbers to trade. Commercial dealings were negotiated between an experienced elder, Nookamis, and Thorn. Thorn offered an exchange rate found to be unsatisfactory by the elder, who wanted five blankets for every fur skin sold.[37] These discussions continued on throughout the day and Thorn increasingly became frustrated at the indigenous intransigence to accept his terms. The interpreter later informed McDougall that Thorn "got in a passion with Nookamis", taking one of Nookamis' fur skins and hitting him on the face with it.[37] After this outburst, Thorn ordered the ship prepare to depart, with the Tla-o-qui-aht still on board.

The Tla-o-qui-aht consulted among themselves and on 15 June, as Tonquin was close to leaving the area, offered to trade their fur stockpiles again. They proposed that in return for a skin, the PFC officers sell three blankets and a knife. McDougall recounted that "A brisk trade was carried on untill all the Indians setting round on the decks of the Ship were supplied with a knife a piece."[38] Violence immediately erupted as warriors led by Wickaninnish attacked the crew on board, killing all but four of the men. Three crew members escaped in a rowboat during the confusion, and one badly wounded man, James Lewis, was left aboard the ship. The following day, 16 June, Lewis allegedly scuttled Tonquin by lighting a fuse that detonated the ship's powder magazine when the Tla-o-qui-aht returned to loot the ship; the explosion may have killed more than 100 natives. The crew members who had escaped during the initial massacre were allegedly captured and tortured to death by the Tla-o-qui-aht following the explosion. The only known survivor of the crew was Joseachal, who arrived back at Fort Astoria with the assistance of prominent Lower Chinookan noble Comcomly.[37] His account is the only one detailing the fate of the Tonquin.

Legacy

editNotable namesakes include Tonquin Beach in Tofino, Canada; and Tonquin Valley and Tonquin Pass, both in the Canadian Rockies. A movie was in planning stages in 2008, to portray the events ending with the 1811 destruction of Tonquin.[39]

See also

edit- John R. Jewitt, whose ship Boston was similarly captured nearby

Citations

edit- ^ a b c d e Fanning 1838, p. 84.

- ^ Irving (1836), p. 58

- ^ a b c Franchère 1854, pp. 47–49.

- ^ a b c d e Ross 1849, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Jones 1997, p. 300.

- ^ Fanning 1838, p. 105.

- ^ Fanning 1838, p. 94.

- ^ Fanning 1838, p. 102.

- ^ Fanning 1838, p. 110.

- ^ a b Fanning 1838, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Fanning 1838, pp. 119–121.

- ^ a b Fanning 1838, pp. 123–126.

- ^ Fanning 1838, pp. 129–131.

- ^ Fanning 1838, p. 135.

- ^ Gough, Barry M. "Tonquin". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Eddins 2007.

- ^ Franchère 1854, p. 31.

- ^ Begg 1894, p. 7.

- ^ Franchère 1854, pp. 29–31.

- ^ Ross 1849, p. 16.

- ^ Franchère 1854, pp. 35–36.

- ^ a b Ross 1849, p. 19.

- ^ Franchère 1854, p. 41.

- ^ Franchère 1854, pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b Franchère 1854, p. 55.

- ^ a b c Ross 1849, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Franchère 1854, p. 81.

- ^ Franchère 1854, p. 59.

- ^ Franchère 1854, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Ross 1849, p. 34.

- ^ Franchère 1854, p. 84.

- ^ Duncan 1973, p. 95.

- ^ Ross 1849, p. 52.

- ^ Franchère 1854, pp. 86–88.

- ^ Franchère 1854, p. 94.

- ^ Franchère 1854, p. 102.

- ^ a b c d Jones 1997, pp. 301–302.

- ^ Jones 1997, p. 308.

- ^ "The Suicide Bomber of Clayoquot Sound, Revived". The Tyee. 14 March 2008.

Bibliography

edit- Begg, Alexaner (1894), History of British Columbia from its earliest discovery to the present time, Toronto: William Briggs, archived from the original on 2016-03-05, retrieved 2008-07-13

- Duncan, Janice K. (1973), "Kanaka World Travelers and Fur Company Employees, 1785–1860", Hawaiian Journal of History, 7, Hawaiian Historical Society: 95, hdl:10524/133

- Eddins, O. Ned (2007), "Astorians And The Pacific Fur Company – The First Company To Trap The Pacific Northwest Area", The Fur Trade role in Western Expansion, TheFurTrapper.com, retrieved 2017-01-08

- Fanning, Edmund (1838), Voyages to the South Seas, Indian and Pacific Oceans (4th ed.), New York: William H. Vermilye

- Franchère, Gabriel (1854), Narrative of a voyage to the Northwest coast of America, in the years 1811, 1812, 1813, and 1814, or, The first American settlement on the Pacific, translated by J. V. Huntington, New York City: Redfield

- Irving, Washington (1836), Astoria: or, Enterprise beyond the Rocky Mountains, Richard Bentley

- Jones, Robert F. (1997), "The Identity of the Tonquin's Interpreter", Oregon Historical Quarterly, 98 (3), Oregon Historical Society: 296–314

- Ross, Alexander (1849), Adventures of the first settlers on the Oregon or Columbia River, London: Smith, Elder and Co., ISBN 9780598286024

External links

edit- Account of Tonquin Massacre by Edgar Allan Poe

- Tonquin Anchor

- History Link.org – Tonquin sights the mouth of the Columbia River (essay 8673)

- "Astoria" (1836) by Washington Irving – Project Gutenberg