Thomas Earle (1754–1822) was an English slave trader.[1] He was responsible for at least 73 slave voyages and alongside his brother he transported over 19,000 enslaved people. Of these 3,000 died on board his ships. One of his ships, Annabella, was seized by the British Crown for slave trading with the enemy. He was Mayor of Liverpool in 1787.

Early life

editEarle was born in Liverpool in 1754.[2] He was the son of William Earle, who was also a slave trader.[3] He attended Manchester Grammar School from the age of 11. There are no records to indicate that he had been a slave ship captain like his father. His obituary stated that he had spent some time in his childhood in Italy and in his later life he wintered in the country.[4]

Slave trader

editEarle was responsible for at least 73 slave voyages in a period spanning the twenty years between 1779 and 1799.[2]

Earle was the son of William Earle, who was also a slave trader. He spent much of his time in the slavery industry alongside his brother William Earle.[3] He and his brother mostly traded under the name T. & W. Earle. For a UK parliamentary commission dated 3 March 1790, the company was listed as the sixth biggest in Liverpool.[5] The Earle brothers traded at least 19,000 enslaved people of whom 3,000 died on board their ships. During this period they had a particularly high mortality rate of 13%. One of their ships Liverpool Hero left Calabar with 560 enslaved people, but 330 of them died before arriving at Dominica. In their early voyages the Earle's took enslaved people from Bonny, the Cameroons, Calabar and Whydah.[6]

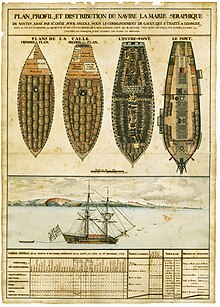

An account of the Earle's slave trading was recorded by William Butterworth, a boy who was tricked into signing up to sail on Hudibras. He wrote that the ship arrived in Old Calabar where two other Earle ships were already in harbour. Butterworth describes the enslaved people as "the unfortunate sons and daughters of Africa".[7] He described how Hudibras was fortified and partitioned to ensure the captives could not escape. It was around six months before Hudibras was full and set sail with 360 enslaved people.[7]

Butterworth described one event whereby the captain of the Hudibras was met by an African vessel containing a single cannon and 12–14 African men armed with guns and swords. The leader of this ship offered to sail up the river and capture people who he would then sell to the captain. Butterworth described the practice of using "Pawns"; an African slave trader would take payment in advance of delivering captives, but leave a relative of theirs on board. If the slave trader did not return, then their relative would be enslaved.[8]

Thomas Earle had his slave-ship Annabella confiscated by the British Crown in 1804.[9] Britain was at war, but the captain of Annabella, John McClure, bought 140 male and 63 female enslaved people from the Governor of Elmina, which was controlled by the Dutch, an enemy state. Annabella was seized by Edward Stirling Dickson, Captain of HMS Inconstant.[10] Captain Dickson had orders to sail the African coast and capture enemy vessels, when he received news that Annabella was moored off Elmina he set sail to investigate and discovered that McClure had bought the enslaved people from the enemy.[10] It is likely that McClure had orders from Earle to behave in this illegal way. Earle's insurers Lloyd's of London listed the ship as confiscated "for illicit trade".[10] McClure protested his innocence to no avail. Shortly after this Earle exited the slave trade, around 3 years before it was officially abolished with the Slave Trade Act 1807. It is likely that the incident with Annabella was a factor in Earle's decision to leave the trade.[11]

Mayor of Liverpool

editEarle was Mayor of Liverpool in 1787–1788.[12] In 1787, 37 of the 41 members of the Liverpool council were slavers, as were all 20 mayors from this year until abolition in 1807.[13]

Personal life

editEarle married his first cousin Mary Earle and they had seven children, including the railway investor Hardman Earle.[14]

Earle's wider family were also slave traders. Thomas's father, grandfather, brother and other relatives were all slavers.[15]

The Earle Collection

editA collection of papers and documents relating to the Earle family is held by the Merseyside Maritime Museum in Liverpool. The papers are of significant importance to the research of the slave trade. The papers were collected by a family member T. Algernon Earle in the 19th century. They were discovered by David Richardson of Hull University, and in 1993 the owner Sir George Earle donated them to the Maritime Museum.[16]

References

edit- ^ Earle 2015, p. 195.

- ^ a b Richardson 2007, p. 198.

- ^ a b Earle 2015, p. 193.

- ^ Earle 2015, p. 194.

- ^ Earle 2015, p. 199.

- ^ Earle 2015, p. 200.

- ^ a b Earle 2015, p. 203.

- ^ Earle 2015, p. 204.

- ^ Earle 2015, p. 214.

- ^ a b c Earle 2015, p. 213.

- ^ Earle 2015, pp. 213–214.

- ^ "Former Mayors and Lord Mayors". Liverpool Town Hall.

- ^ "British History in depth: The Business of Enslavement". bbc.co.uk.

- ^ "Summary of Individual | Legacies of British Slavery". ucl.ac.uk.

- ^ Earle 2015, p. 196.

- ^ "The Earle Collection" – via National Archive of the UK.

Sources

edit- Earle, Peter (2015). The Earles of Liverpool. Liverpool, UK: Liverpool University Press.

- Richardson, David (2007). Liverpool and Transatlantic Slavery. Liverpool, UK: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-84631-066-9.