Delaware Canal State Park is a 830-acre (336 ha) Pennsylvania state park in Bucks and Northampton Counties in Pennsylvania. The main attraction of the park is the Delaware Canal which runs parallel to the Delaware River between Easton and Bristol.

| Delaware Canal State Park | |

|---|---|

A trail along the Delaware Canal | |

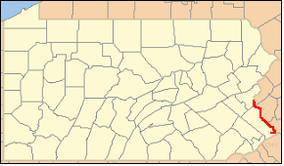

Location of Delaware Canal State Park in Pennsylvania | |

| Location | Pennsylvania, United States |

| Coordinates | 40°33′01″N 75°05′08″W / 40.55028°N 75.08556°W |

| Area | 830 acres (340 ha) |

| Elevation | 127 ft (39 m) |

| Established | 1931 |

| Named for | Delaware Canal |

| Governing body | Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources |

| Website | Delaware Canal State Park |

The Delaware River is the longest free-flowing river east of the Mississippi River in the United States. It serves as a major migration path for American Shad and waterfowl. A visitor center is located at New Hope and the park management office is located in Upper Black Eddy. Within the park are two designated natural areas: Nockamixon Cliffs and River Islands. Recreational opportunities include hiking, biking and cross-country skiing along the towpath, fishing in the canal and river, and canal boat rides.

Delaware Canal State Park was chosen by the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR) and its Bureau of Parks as one of "25 Must-See Pennsylvania State Parks".[1]

The Delaware Canal State Park frequently floods. The path was restored recently but was washed out again due to flooding in April 2011. Canal paths for the Delaware and Raritan Canal on the New Jersey side of the Delaware have not suffered the same damage.

Course

editThe Delaware Canal runs from the mouth of the Lehigh River in Easton along the Delaware River south to Bristol. The land along the canal is a mixture of private property and state park lands, with the state park covering some 830 acres (336 ha) along the 60 miles (97 km) of the canal.[2][3]

The course of Delaware Canal State Park is as follows: leaving Easton, the canal enters Williams Township in Northampton County, and heads south paralleling the Delaware River.[3] The park crosses into Bucks County and passes through the following municipalities: the borough of Riegelsville, the townships of Durham, Nockamixon, Bridgeton, Tinicum, Plumstead, and Solebury, the borough of New Hope, back into Solebury Township, Upper Makefield and Lower Makefield townships, the borough of Yardley, back into Lower Makefield Township, and the borough of Morrisville.[2]

The Delaware River has followed a southeast course until now, but after Morrisville in Falls Township it turns approximately ninety degrees to flow southwest. The canal and park turn southwest earlier and leave the river in Morrisville, cutting off this corner. The park and canal pass through Falls Township to the borough of Tullytown, where they again follows a course parallel to the river. From Tullytown the canal passes through Bristol Township and ends at the borough of Bristol.[2]

History

editThe Delaware Canal stretches from Bristol to Easton along the Delaware River. It was used to haul coal and other products from the Lehigh Canal beginning in Mauch Chunk (today Jim Thorpe) to the industrial centers of the Philadelphia area near Bristol, Pennsylvania. The canal was built in the mid-19th century and ran its last commercial traffic on October 17, 1931. The state bought 40 miles (64 km) of the canal in 1931 and bought the remaining 20 miles (32 km) in 1940.[4][5]

The Delaware Division of the Pennsylvania Canal and its towpath became Theodore Roosevelt State Park in the early 1950s, when the berms were restored and the canal was refilled with water. The park was renamed Delaware Canal State Park in 1989. The U.S. Congress designated the Delaware Canal as a Registered National Historic Landmark and its towpath is a National Recreation Trail.

From the mid 1950s until 2006, visitors to the park were given the chance to explore the canal in mule-drawn canal boats operated from a landing at Lock 11 in New Hope, and operated north of that point, terminating about 1 mile (1.6 km) north of the Lock 11 landing, near the Rabbit Run and U.S. Route 202 bridges, but was able to navigate all the way to the Virginia Forrest Recreation Area, about 4.5 miles (7.2 km) north of the Lock 11 landing for private parties. Due to lack of maintenance of the canal by DCNR and floods, the barge concession was forced out of business.

Natural areas

editPennsylvania state park natural areas are special areas that are set aside within the state parks to allow the natural condition of biological and physical processes to operate, usually without human intervention. There are two such areas at the Delaware Canal State Park: River Islands and Nockamixon Cliffs. These natural areas are set aside to provide scientists with the chance to observe the natural ecosystems at work and to protect examples of unique and typical plant life, animal habitats, and to protect examples of natural beauty.[6][7]

River islands

editThere are eleven islands in the Delaware River that are protected from further development. The islands contain archeological clues to the past, provide habitats for migrating waterfowl and songbirds, and offer recreational opportunities in a wild setting for fisherman and canoeists.[6][7]

Some of the islands were originally part of the shoreline of the river and have since been cut off by the effects of erosion, river movement or intervention by man, but other islands have been built up naturally in the river. These river islands grew from silt deposits that attracted seeds. The seeds grew into plants and trees. The roots of the plants and trees caused the further building of silt and dirt and lead to the formation of the islands. These islands are mostly stable but can be shifted by the erosion effects of the river and flooding.[6][7]

Nockamixon Cliffs

editThe cliffs along the Delaware River, known as Nockamixon Cliffs, appear to rise from the land, but are in fact formations of very hard stone that have eroded at a much slower pace than the surrounding land. These cliffs are made of weather resistant rock called hornfel, formed at the end of the Triassic Period when magma rose up from deep within the Earth's crust and flowed into beds of sedimentary rock. The cliffs "rose" during the Jurassic Period when the surrounding sandstone and shale was eroded by wind and water.[6][7]

The Nockamixon Cliffs are situated along the river in such a way that the north facing cliffs in Pennsylvania receive little to no direct sunlight, causing their temperatures to be cooler than normal. The cool habitat supports an alpine-Arctic plant community that is very unusual for the latitude of Delaware Canal State Park. The south facing cliffs in New Jersey at Delaware and Raritan Canal State Park have a nearly opposite habitat. They receive a high amount of sunshine, which makes the area near the cliffs warmer and drier than usual, creating a habitat for plants that normally thrive in much more arid areas.[6][7]

American shad

editThe Delaware River is used by American shad during their spawning run. The fish are the largest members of the herring family. They are an anadromous species, which means they are born and spawn in fresh water but spend the majority of their lives in salt water (of the Atlantic Ocean). After spending three to six years at sea, the shad return to the waters of their birth to spawn. Unlike salmon, not all shad die after spawning; some survive and return to the ocean.[8]

The American Shad have long been a vital food resource for the people living along the Delaware River. The Lenape (or Delaware) tribe depended on the migration of the shad as a staple of their diet. They harvested the fish and prepared them in several ways. Some fish were grilled quickly on wooden racks and others were preserved for later use by smoking them or air drying. The Moravians and other early European settlers in the Delaware River Valley also depended on shad for their diets.[8]

The booming population along the Delaware River, especially in Philadelphia, Easton, Camden and Trenton, led to increased levels of pollution in the Delaware River. Sewage and industrial pollution combined with extensive overfishing nearly led to a total collapse of the shad population. The pollution was so bad that in the years following World War II nearly 20 miles (32 km) of the river was a dead zone, free of dissolved oxygen. This dead zone prevented the migration of shad. Dams built during the canal era to provide water for the canals also limited the migration patterns of the shad. The combination of dams and pollution nearly caused the shad to abandon the Delaware River and its tributaries altogether.[8]

Beginning in the late 1960s, an effort began to re-establish the population of American Shad in the Delaware River basin. Pollution levels dropped tremendously, and fish ladders were built to allow the shad to bypass the dams that blocked their way and to migrate further up the river. These efforts have led to the restoration of the American Shad in the Delaware River.[8]

Recreation

editThe Delaware Canal towpath runs along the canal for 60 miles (97 km) from Easton to Bristol and was once used by teams of mules as they towed the barges up and down the canal. Today it is a National Recreational Trail open to walkers, joggers, cyclists, bird watchers and cross-country skiers. Five bridges over the Delaware River connect the paths in Delaware Canal State Park with paths in New Jersey at the Delaware and Raritan Canal State Park.[4]

The Delaware River and the Delaware Canal are warm water fisheries. Common game fish include the American shad, striped bass, walleye and smallmouth bass. The river is also popular with people who wish to explore it in canoes and other small non-powered watercraft. All boats must have a launch permit for Pennsylvania or New Jersey or a current registration from any state.[4]

Nearby state parks

editThe following state parks are within 30 miles (48 km) of Delaware Canal State Park:[2][3][9][10]

- Beltzville State Park (Carbon County)

- Benjamin Rush State Park (Philadelphia County)

- Big Pocono State Park (Monroe County)

- Bull's Island State Park (New Jersey)

- Delaware and Raritan Canal State Park (New Jersey)

- Evansburg State Park (Montgomery County)

- Fort Washington State Park (Montgomery County)

- Hacklebarney State Park (New Jersey)

- Jacobsburg Environmental Education Center (Northampton County)

- Neshaminy State Park (Bucks County)

- Nockamixon State Park (Bucks County)

- Norristown Farm Park (Montgomery County)

- Ralph Stover State Park (Bucks County)

- Rancocas State Park (New Jersey)

- Ridley Creek State Park (Delaware County)

- Round Valley State Park (New Jersey)

- Tyler State Park (Bucks County)

- Voorhees State Park (New Jersey)

- Washington Crossing State Park (New Jersey)

- Washington Rock State Park (New Jersey)

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Find a Park: 25 Must-see Parks". Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Archived from the original on September 26, 2011. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- ^ a b c d 2007 General Highway Map Bucks County Pennsylvania (PDF) (Map). 1:65,000. Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, Bureau of Planning and Research, Geographic Information Division. Retrieved July 27, 2006.[permanent dead link] Note: shows Delaware Canal State Park

- ^ a b c 2006 General Highway Map Northampton County Pennsylvania (PDF) (Map). 1:65,000. Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, Bureau of Planning and Research, Geographic Information Division. Retrieved July 27, 2006.[permanent dead link] Note: shows Delaware Canal State Park

- ^ a b c "Delaware Canal State Park". Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved November 27, 2006.

- ^ "Delaware Canal". National Canal Museum. Archived from the original on February 5, 2012. Retrieved February 27, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e "Delaware Canal State Park - A Day on the Canal". Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Archived from the original on December 11, 2006. Retrieved January 2, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e "Delaware Canal State Park - Natural Areas". Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Archived from the original on December 11, 2006. Retrieved January 2, 2007.

- ^ a b c d "Delaware Canal State Park - The American Shad". Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Archived from the original on December 11, 2006. Retrieved January 2, 2007.

- ^ "Find a Park by Region (interactive map)". Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Archived from the original on September 24, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ Michels, Chris (1997). "Latitude/Longitude Distance Calculation". Northern Arizona University. Archived from the original on April 11, 2008. Retrieved April 20, 2008.

External links

edit- "Delaware Canal State Park official map" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016. (1367 KB)