Themes in Fyodor Dostoevsky's writings

This article is missing information about the themes of existentialism and Russian nihilism in Dostoevsky's works. (September 2020) |

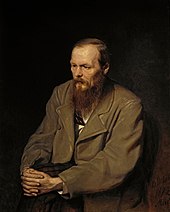

The themes in the writings of Russian writer Fyodor Dostoevsky (frequently transliterated as "Dostoyevsky"), which consist of novels, novellas, short stories, essays, epistolary novels, poetry,[1] spy fiction[2] and suspense,[3] include suicide, poverty, human manipulation, and morality. Dostoevsky was deeply Eastern Orthodox and religious themes are found throughout his works, especially in those written after his release from prison in 1854. His early works emphasised realism and naturalism, as well as social issues such as the differences between the poor and the rich. Elements of gothic fiction, romanticism, and satire can be found in his writings. Dostoyevsky was "an explorer of ideas",[4] greatly affected by the sociopolitical events which occurred during his lifetime. After his release from prison his writing style moved away from what Apollon Grigoryev called the "sentimental naturalism" of his earlier works and became more concerned with the dramatization of psychological and philosophical themes.

Themes and style

editThough sometimes described as a literary realist, a genre characterized by its depiction of contemporary life in its everyday reality, Dostoevsky saw himself as a "fantastic realist".[5] According to Leonid Grossman, Dostoevsky wanted "to introduce the extraordinary into the very thick of the commonplace, to fuse... the sublime with the grotesque, and push images and phenomena of everyday reality to the limits of the fantastic."[6] Grossman saw Dostoevsky as the inventor of an entirely new novelistic form, in which an artistic whole is created out of profoundly disparate genres—the religious text, the philosophical treatise, the newspaper, the anecdote, the parody, the street scene, the grotesque, the pamphlet—combined within the narrative structure of an adventure novel.[7] Dostoevsky engages with profound philosophical and social problems by using the techniques of the adventure novel as a means of "testing the idea and the man of the idea".[8] Characters are brought together in extraordinary situations for the provoking and testing of the philosophical ideas by which they are dominated.[9] For Mikhail Bakhtin, 'the idea' is central to Dostoevsky's poetics, and he called him the inventor of the polyphonic novel, in which multiple "idea-voices" co-exist and compete with each other on their own terms, without the mediation of a 'monologising' authorial voice. It is this innovation, according to Bakhtin, that made the co-existence of disparate genres within an integrated whole artistically successful in Dostoevsky's case.[10]

Bakhtin argues that Dostoyevsky's works can be placed in the tradition of menippean satire. According to Bakhtin, Dostoyevsky revived satire as a genre combining comedy, fantasy, symbolism, adventure, and drama in which mental attitudes are personified. The short story Bobok, found in A Writer's Diary, is "one of the greatest menippeas in all world literature", but examples can also be found in "The Dream of a Ridiculous Man", the first encounter between Raskolnikov and Sonja in Crime and Punishment, which is "an almost perfect Christianised menippea", and in "The Legend of the Grand Inquisitor".[11] Critic Harold Bloom stated that "satiric parody is the center of Dostoyevsky's art."[12]

Dostoyevsky investigated human nature. According to his friend, the critic Nikolay Strakhov, "All his attention was directed upon people, and he grasped at only their nature and character", and was "interested by people, people exclusively, with their state of soul, with the manner of their lives, their feelings and thoughts". Philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev stated that he "is not a realist as an artist, he is an experimenter, a creator of an experimental metaphysics of human nature". His characters live in an unlimited, irrealistic world, beyond borders and limits. Berdyaev remarks that "Dostoevsky reveals a new mystical science of man", limited to people "who have been drawn into the whirlwind".[13]

Dostoyevsky's works explore the irrational, dark motifs, dreams, emotions and visions. He was an avid reader of the Gothic and enjoyed the works of Radcliffe, Balzac, Hoffmann, Charles Maturin and Soulié. Among his first Gothic works was The Landlady. The stepfather's demonic fiddle and the mysterious seller in Netochka Nezvanova are Gothic-like. Other aspects of the genre can be found in Crime and Punishment, for example the dark and dirty rooms and Raskolnikov's Mephistophelian character, and in the descriptions of Nastasia Filippovna in The Idiot and Katerina Ivanovna in The Brothers Karamazov.[14]

Dostoyevsky's use of space and time were analysed by philologist Vladimir Toporov. Toporov compares time and space in Dostoyevsky with film scenes: the Russian word vdrug (suddenly) appears 560 times in the Russian edition of Crime and Punishment, reinforcing the atmosphere of tension characteristic of the book.[15] Dostoyevsky's works often use precise numbers (at two steps ... , two roads to the right), as well as high and rounded numbers (100, 1000, 10000). Critics such as Donald Fanger[16] and Roman Katsman, writer of The Time of Cruel Miracles: Mythopoesis in Dostoevsky and Agnon, call these elements "mythopoeic".[17]

Suicides are found in several of Dostoyevsky's books. The 1860s–1880s marked a near-epidemic period of suicides in Russia, and many contemporary Russian authors wrote about suicide. Dostoyevsky's suicide victims and murderers are often unbelievers or tend towards unbelief: Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment, Ippolit in The Idiot, Kirillov and Stavrogin in Demons, and Ivan Karamazov and Smerdiakov in The Brothers Karamazov. Disbelief in God and immortality and the influence of contemporary philosophies such as positivism and materialism are seen as important factors in the development of the characters' suicidal tendencies. Dostoyevsky felt that a belief in God and immortality was necessary for human existence.[18][19]

Early writing

editDostoyevsky's translations of Balzac's Eugénie Grandet and Sand's La dernière Aldini differ from standard translations. In his translation of Eugénie Grandet, he often omitted whole passages or paraphrased significantly, perhaps because of his rudimentary knowledge of French or his haste.[20] He also used darker words, such as "gloomy" instead of "pale" and "cold", and sensational adjectives, such as "horrible" and "mysterious". The translation of La desnière Aldini was never completed because someone already published one in 1837.[21] He also abandoned working on Mathilde by Sue due to lack of funds.[22] Influenced by the plays he watched during this time, he wrote verse dramas for two plays, Mary Stuart by Schiller and Boris Godunov by Pushkin, which have been lost.[23][24]

Dostoyevsky's first novel, Poor Folk, an epistolary novel, depicts the relationship between the elderly official Makar Devushkin and the young seamstress Varvara Dobroselova, a remote relative. The correspondence between them reveals Devushkin's tender, sentimental adoration for his relative and her confident, warm regard for him as they grapple with the bewildering and sometimes heartbreaking problems forced upon them by their lowly social positions. The novel was a success, with the influential critic Vissarion Belinsky calling it "Russia's first social novel",[25] for its sympathetic depiction of poor and downtrodden people.[26] Dostoyevsky's next work, The Double, was a radical departure from the form and style of Poor Folk. It centres on the disintegrating inner and outer world of its shy and 'honourable' protagonist, Yakov Golyadkin, as he slowly discovers that his treacherous doppelgänger has achieved the social respect and success denied to him. Unlike the first novel, The Double was not well received by critics. Belinsky commented that the work had "no sense, no content and no thoughts", and that the novel was boring due to the protagonist's garrulity, or tendency towards verbal diarrhoea.[27] He and other critics stated that the idea for The Double was brilliant, but that its external form was misconceived and full of multi-clause sentences.[28][29]

The short stories Dostoyevsky wrote during the period before his imprisonment explore similar themes to Poor Folk and The Double.[30] "White Nights" "features rich nature and music imagery, gentle irony, usually directed at the first-person narrator himself, and a warm pathos that is always ready to turn into self-parody". The first three parts of his unfinished novel Netochka Nezvanova chronicle the trials and tribulations of Netochka, stepdaughter of a second-class fiddler, while in "A Christmas Tree and a Wedding", Dostoyevsky switches to social satire.[31]

Dostoyevsky's early works were influenced by contemporary writers, including Pushkin, Gogol and Hoffmann, which led to accusations of plagiarism. Several critics pointed out similarities in The Double to Gogol's works The Overcoat and The Nose. Parallels have been made between his short story "An Honest Thief" and George Sand's François le champi and Eugène Sue's Mathilde ou Confessions d'une jeune fille, and between Dostoyevsky's Netochka Nezvanova and Charles Dickens' Dombey and Son. Like many young writers, he was "not fully convinced of his own creative faculty, yet firmly believed in the correctness of his critical judgement."[31]

Later years

editAfter his release from prison, Dostoyevsky became more concerned with elucidating psychological and philosophical themes, and his writing style moved away from the kind of "sentimental naturalism" found in Poor Folk and The Insulted and Injured.[32] Despite having spent four years in prison in horrendous conditions, he wrote two humorous books: the novella Uncle's Dream and the novel The Village of Stepanchikovo.[33] The House of the Dead is a semi-autobiographical memoir written while Dostoyevsky was in prison and includes religious themes. Characters from the three Abrahamic religions—Judaism, Islam, and Christianity– appear in it, and while the Jewish character Isay Fomich and characters affiliated with the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Old Believers are depicted negatively, the Muslims Nurra and Aley from Dagestan are depicted positively. Aley is later educated by reading the Bible, and shows a fascination for the altruistic message in Christ's Sermon on the Mount, which he views as the ideal philosophy.[34]

The novel Notes from the Underground, which he partially wrote in prison, was his first secular book, with few references to religion. Later, he wrote about his reluctance to remove religious themes from the book, stating, "The censor pigs have passed everything where I scoffed at everything and, on the face of it, was sometimes even blasphemous, but have forbidden the parts where I demonstrated the need for belief in Christ from all this".[35]

Victor Terras speculated that Dostoyevsky's concern with the downtrodden after the publication of Notes from the Underground was "motivated not so much by compassion as by an unhealthy curiosity about the darker recesses of the human psyche, ... by a perverse attraction to the diseased states of the human mind, ... or ... by sadistic pleasure in observing human suffering".[5] Humiliated and Insulted was similarly secular; only at the end of the 1860s, beginning with the publication of Crime and Punishment, did Dostoyevsky's religious themes resurface.[34]

The works Dostoyevsky published in the 1870s explore human beings' capacity for manipulation. The Eternal Husband and "The Meek One" describe the relationship between a man and woman in marriage, the first chronicling the manipulation of a husband by his wife; the latter the opposite. "The Dream of a Ridiculous Man" raises this theme of manipulation from the individual to a metaphysical level.[36] Philosopher Strakhov agreed that Dostoyevsky "a great thinker and a great visionary ... a dialectician of genius, one of Russia's greatest metaphysicians."[37]

Philosophy

editDostoyevsky's works were often called "philosophical", although he described himself as "weak in philosophy".[38] According to Strakhov, "Fyodor Mikhailovich loved these questions about the essence of things and the limits of knowledge".[38] His close friend, the philosopher and theologian Vladimir Solovyov, felt that he was "more a sage and an artist than a strictly logical, consistent thinker."[39] His irrationalism is mentioned in William Barrett's Irrational Man: A Study in Existential Philosophy and in Walter Kaufmann's Existentialism from Dostoevsky to Sartre.[40]

References

edit- ^ Достоевский Федор Михайлович: Стихотворения [Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoyevsky: Poems] (in Russian). Lib.ru. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ^ Cicovacki 2012, p. 80.

- ^ Lantz 2004, p. 170.

- ^ Terras 1998, p. 59.

- ^ a b Terras 1998, p. preface.

- ^ Grossman, Leonid (1925). The Poetics of Dostoevsky. pp. 61–2.

- ^ Grossman, Leonid (1925). The Poetics of Dostoevsky. pp. 174–75.

- ^ Bakhtin, Mikhail (1984). Problems of Dostoevsky's Poetics. University of Minnesota Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-8166-1227-7.

- ^ Bakhtin, Mikhail (1984). p. 114

- ^ Bakhtin, Mikhail (1984). p. 105

- ^ René Wellek. "Bakhtin's View of Dostoevsky: "Polyphony" and "Carnivalesque"". University of Toronto. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- ^ Bloom 2004, p. 10.

- ^ Nikolay Berdyaev (1918). "The Revelation About Man in the Creativity of Dostoevsky". Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- ^ Lantz 2004, pp. 167–170.

- ^ Vladimir Toporov (1995). Мив. Ритуал. Симбол. Образ. [Myth. Ritual. Symbol. Image] (in Russian). Прогресс (Progress). pp. 193–211. ISBN 5-01-003942-7.

- ^ Donald Fanger, Dostoevsky and Romantic Realism: A Study of Dostoevsky in Relation to Balzac, Dickens, and Gogol, Northwestern University Press, 1998, p. 14

- ^ Boris Sergeyevich Kondratiev. "Мифопоэтика снов в творчестве Ф. М. Достоевского" [Mythopoetic Dreams in the Creativity of F. M. Dostoyevsy]. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- ^ Paperno 1997, pp. 123–6.

- ^ Lantz 2004, pp. 424–8.

- ^ Lantz 2004, p. 29.

- ^ Catteau 1989, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Lantz 2004, p. 419.

- ^ Sekirin 1997, p. 51.

- ^ Carr 1962, p. 20.

- ^ Bloom 2004, p. 12.

- ^ Lantz 2004, p. 334-35.

- ^ Belinsky 1847, p. 96.

- ^ Reber 1964, p. 22.

- ^ Terras 1969, p. 224.

- ^ Frank 2009, p. 103.

- ^ a b Terras 1998, pp. 14–30.

- ^ Catteau 1989, p. 197.

- ^ Terras 1998, pp. 32–50.

- ^ a b Bercken 2011, p. 23-6.

- ^ Pisma, XVIII, 2, 73

- ^ Neuhäuser 1993, pp. 94–5.

- ^ Scanlan 2002, p. 2.

- ^ a b Anna Dostoyevskaya, Polnoe sobranie sochinenii F. M. Dostoevskogo, St. Petersburg, 1882–83, 1:225

- ^ Vladimir Solovyov, Sobranie sochinenii Vladimira Sergeevicha Solov'eva, St. Petersburg, Obshchestvennaia Pol'za, 1901–07, 5:382

- ^ Scanlan 2002, p. 3-6.

Bibliography

edit- Belinsky, Vissarion (1847). Polnoye sobranye (in Russian). Vol. 10.

- Bercken, Wil van den (2011). Christian Fiction and Religious Realism in the Novels of Dostoevsky. Anthem Press. ISBN 978-0-85728-976-6.

- Bloom, Harold (2004). Fyodor Dostoevsky. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7910-8117-4.

- Carr, Edward Hallett (1962). Dostoevsky 1821–1881. Taylor & Francis. OCLC 319723.

- Catteau, Jacques (1989). Dostoyevsky and the Process of Literary Creation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-32436-6.

- Cicovacki, Predrag (2012). Dostoevsky and the Affirmation of Life. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4128-4606-6.

- Frank, Joseph (2009). Dostoevsky: A Writer in His Time. Vol. 1–5. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12819-1.

- Kjetsaa, Geir (15 January 1989). A Writer's Life. Fawcett Columbine.

- Lantz, Kenneth A. (2004). The Dostoevsky Encyclopedia. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-30384-5.

- Neuhäuser, Rudolf (1993). F.M. Dostoejevskij: Die Grossen Romane und Erzählungen; Interpretationen und Analysen (in German). Vienna; Cologne; Weimar: Böhlau Verlag. ISBN 978-3-205-98112-1.

- Paperno, Irina (1997). Suicide As a Cultural Institution in Dostoevsky's Russia. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8425-4.

- Reber, Natalie (1964). Studien zum Motiv des Doppelgängers bei Dostojevskij und E.T.A. Hoffmann (in German). Marburg Arbeitsgemeinsch. f. Osteuropaforsch. d. Philipps-Universität. ISBN 9783877110805.

- Scanlan, James Patrick (2002). Dostoevsky the Thinker. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3994-0.

- Sekirin, Peter (1997). The Dostoevsky Archive: Firsthand Accounts of the Novelist from Contemporaries' Memoirs and Rare Periodicals, Most Translated Into English for the First Time, with a Detailed Lifetime Chronology and Annotated Bibliography. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-0264-9.

- Terras, Victor (1969). The Young Dostoevsky: A critical study. Slavistic Printings and Reprintings. The Hague & Paris: Mouton. LCCN 69-20326.

- Terras, Victor (1998). Reading Dostoevsky. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-16054-8.