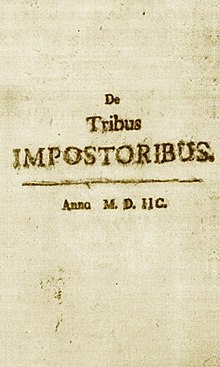

The Treatise of the Three Impostors (Latin: De Tribus Impostoribus) was a long-rumored book denying all three Abrahamic religions: Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, with the "impostors" of the title being Jesus, Moses, and Muhammad. Hearsay concerning such a book surfaces by the 13th century and circulates through the 17th century. Authorship of the hoax book was variously ascribed to Jewish, Muslim, and Christian writers.[1] Fabrications of the text eventually begin clandestine circulation, with a notable French underground edition Traité sur les trois imposteurs first appearing in 1719.

Timeline of the myth

edit| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 10th century | Abu Tahir al-Jannabi uses a "three impostors" slogan for political ends.[2] |

| 1239 | Pope Gregory IX in an encyclical ascribes a view of the Abrahamic religions as founded by "three impostors" to Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor.[3] Through Pietro della Vigna, the excommunicated Emperor denies heresy, explicitly saying that the three impostors theory has not passed his lips.[4] |

| Later in the 13th century | Thomas de Cantimpré ascribes such views to Simon of Tournai (c. 1130–1201).[5] |

| 14th century | Opponents of Averroism accuse Averroes of originating the "three impostors" view.[6] |

| c. 1350 | The Decameron by Boccaccio alludes to the "three impostors" motif in terms of religious relativism.[7] |

| 1643 | Thomas Browne ascribes authorship of such a work to Bernardino Ochino.[8] |

| 1656 | Henry Oldenburg reports that at Oxford a politicised "three impostors" theory is current.[9] |

| 1669 | John Evelyn publishes a work under a "three impostors" title, aimed at Sabbatai Zevi.[10] The others named were Padre Ottomano, and Mahomed Bei, pseudonym of the adventurer Joannes Michael Cigala.[11][12] |

| 1680 | As De tribus impostoribus magnis, Christian Kortholt the elder publishes an attack on Edward Herbert of Cherbury, Thomas Hobbes and Benedict Spinoza.[13] |

| 1680s? | De imposturis religionum was an anonymous attack on Christianity that surfaced late in the 17th century. Internal evidence makes it unlikely that the work was completed before 1680.[14] It became known at the auction in 1716 of the library of the Greifswald theologian Johann Friedrich Mayer. This work is attributed to the jurist Johannes Joachim Müller (1661–1733).[15] |

| 1680s | Likely initial composition of the Traité sur les trois imposteurs, in association with Spinozan publicists. See below for its adaptation and promotion from the Netherlands. |

| 1693 | Bernard de la Monnoye writes to Pierre Bayle, claiming that no "three impostors" tract exists.[16] |

| 1709 | John Bagford in a letter comments on the deist John Toland's efforts to pass off Spaccio by Giordano Bruno as the Treatise of the Three Impostors; and says he knows of no such genuine Treatise.[17] |

| 1712 | De la Monnoye's letter to Bayle is reprinted, as part of his edition Menagiana, an -iana from the works of Gilles Ménage.[18] After reprinting again, in Paris and Amsterdam, it met with an anonymous Réponse in 1716, that has been attributed to Rousset de Missy.[19] With that, the events leading to the publication of a hoax "Treatise" had begun. |

Traité sur les trois imposteurs, from 1719

editThe work that came to be known by this name was published in the early eighteenth century. There were eight published editions, from 1719 to 1793. There was also clandestine circulation. The Traité sur les trois imposteurs has been reckoned the most important example of the underground literature in French of the period.[20]

The work purported to be a text handed down from generation to generation. It can be traced to the circle around Prosper Marchand, who included Jean Aymon and Jean Rousset de Missy. It detailed how the three major figures of Biblical religion in fact misrepresented what had happened to them.

According to Silvia Berti, the book was originally published as La Vie et L'Esprit de Spinosa (The Life and Spirit of Spinoza), containing both a biography of Benedict Spinoza and the anti-religious essay, and was later republished under the title Traité sur les trois imposteurs.[21] The creators of the book have been identified by documentary evidence as Jean Rousset de Missy and the bookseller Charles Levier.[22] The author of the book may have been a young Dutch diplomat called Jan Vroesen or Vroese.[21][22] Another candidate, to whom Levier attributed the work, is Jean-Maximilien Lucas.[23] Israel places its composition in the 1680s.[24]

The content of the Traité has been traced primarily to Spinoza, but with subsequent additions drawn from the ideas of Pierre Charron, Thomas Hobbes, François de La Mothe Le Vayer, Gabriel Naudé and Lucilio Vanini. The reconstruction of the group of authors, given the original text, goes as far as Levier and others such as Aymon and Rousset de Missy. An account based on the testimony of the brother of the publisher Caspar Fritsch, an associate of Marchand, has Levier in 1711 borrowing the original text from Benjamin Furly.[24]

Events from 1719

edit| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 1765 | Archibald Maclaine, in an annotation to his translation of Johann Lorenz Mosheim's Institutes, gives a history of the Traité based on Prosper Marchand's, and attributes the content to the Spaccio of Bruno, and the Spirit of Spinoza, as worked over by compilers.[25] |

| 1770 | Voltaire publishes Épître à l'Auteur du Livre des Trois Imposteurs, a response to the hoax. It contains his remark "If God didn't exist, it would be necessary to invent Him." |

As trope

editIt has been suggested that the "three impostors" as trope can be seen as the negative form of the "ring parable", as used in Lessing's Nathan the Wise.[26]

References

edit- ^ Kohler, Kaufmann; Loewenthal, A. (1806). "Averroes, or Abul Walid Muhammed Ibn Ahmad Ibn Roshd". Jewish Encyclopedia.

- ^ Pines, S.; Yovel, Y. (2012). Maimonides and Philosophy. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 239–240. ISBN 978-94-009-4486-2.

- ^ Minois, Georges (2012). The Atheist's Bible: The Most Dangerous Book That Never Existed. University of Chicago Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-226-53029-1.

- ^ Cleve, Thomas Curtis Van (1972). The Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen, immutator mundi. Clarendon Press. pp. 432–433.

- ^ Shagrir, Iris (2019). The Parable of the Three Rings and the Idea of Religious Toleration in European Culture. Springer Nature. p. 52. ISBN 978-3-030-29695-7.

- ^ Deanesly, Margaret (2004). A History of the Medieval Church: 590-1500. Routledge. p. 205. ISBN 978-1-134-95533-6.

- ^ Schwarz, Hans (1991). Method and Context as Problems for Contemporary Theology: Doing Theology in an Alien World. Edwin Mellen Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-7734-9677-4.

- ^ Minois, Georges (2012). The Atheist's Bible: The Most Dangerous Book That Never Existed. University of Chicago Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-226-53029-1.

- ^ Force, J. E.; Popkin, R. H. (2012). Essays on the Context, Nature, and Influence of Isaac Newton's Theology. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 35. ISBN 978-94-009-1944-0.

- ^ Popkin, Richard Henry (1992). The Third Force in Seventeenth Century Thought. Brill. p. 363. ISBN 978-90-04-09324-9.

- ^ Keynes, Geoffrey (1934). John Evelyn a Study in Bibliophily. CUP Archive. p. 196.

- ^ Matar, Professor Nabil; Matar, Nabil (1998). Islam in Britain, 1558-1685. Cambridge University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-521-62233-2.

- ^ De tribus impostoribus: Anno MDIIC;2. mit einem neuen Vorwort versehene (in German). Henninger. 1876. p. vi.

- ^ Bloch, Olivier (1999). L'identification du texte clandestin aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles: Actes de la journée de Créteil du 15 mai 1998 (in French). Presses Paris Sorbonne. p. 28. ISBN 978-2-84050-130-5.

- ^ Tournoy, Gilbert (1999). Humanistica Lovaniensia: Journal of Neo-Latin Studies. Leuven University Press. p. 432. ISBN 978-90-6186-972-6.

- ^ Laursen, John Christian (1994). New Essays on the Political Thought of the Huguenots of the Refuge. Brill. p. 92. ISBN 978-90-04-24714-7.

- ^ Champion, Justin (2003). Republican Learning: John Toland and the Crisis of Christian Culture, 1696-1722. Manchester University Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-7190-5714-4.

- ^ Israel, Jonathan I. (2002). Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity 1650–1750. OUP Oxford. p. 699. ISBN 9780191622878.

- ^ Laursen, John Christian (1995). New Essays on the Political Thought of the Huguenots of the Refuge. Brill. p. 92. ISBN 978-90-04-09986-9.

- ^ Artigas-Menant, Geneviève; McKenna, Antony (2000). Anonymat et clandestinité aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles: actes de la journée de Créteil du 11 juin 1999 (in French). Presses Paris Sorbonne. p. 259. ISBN 978-2-84050-163-3.

- ^ a b Berti's essay in Atheism from the Reformation to the Enlightenment edited by Michael Hunter and David Wootton. Clarendon, 1992. ISBN 0-19-822736-1

- ^ a b Jacob, Margaret C. (2001). The Enlightenment: A Brief History with Documents. Bedford/St. Martin's. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-312-23701-1.

- ^ Israel, Jonathan I. (2002). Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity 1650–1750. OUP Oxford. pp. 696–7. ISBN 9780191622878.

- ^ a b Israel, Jonathan I. (2002). Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity 1650–1750. OUP Oxford. p. 695. ISBN 9780191622878.

- ^ Mosheim, Johann Lorenz (1878). Mosheim's Institutes of Ecclesiastical History, Ancient and Modern: A New and Literal Translation from the Original Latin, with Copious Additional Notes, Original and Selected. W. Tegg and Company. p. 437 note 3.

- ^ Forst, Rainer (2013). Toleration in Conflict: Past and Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-521-88577-5.

Further reading

edit- Anderson, Abraham (1997). The Treatise of the Three Imposters and the Problem of the Enlightenment. A New Translation of the Traité des Trois Imposteurs (1777 ed.). Lenham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-8476-8430-X.

- Presser, Jacob (1926). Das Buch "De Tribus Impostoribus" (Von den drei Betrügern). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: H. J. Paris (Doctoral dissertation, University of Amsterdam, with the highest distinction, written and published in German); 169 p.

External links

edit- Full Text of Müller's De Tribus Impostoribus provided by infidels.org

- Müller's Tribus Impostoribus in the original Latin, provided by Bibliotheca Augustana (archive)

- Bio on Friedrick II -- subheading "Struggle with the papacy." (3/5ths of the way down the page) from the Encyclopædia Britannica