The Book of Taliesin (Welsh: Llyfr Taliesin) is one of the most famous of Middle Welsh manuscripts, dating from the first half of the 14th century though many of the fifty-six poems it preserves are taken to originate in the 10th century or before.

| Book of Taliesin | |

|---|---|

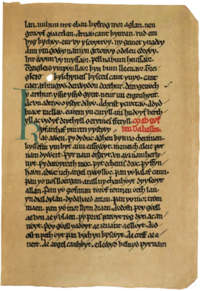

| Aberystwyth, NLW, Peniarth MS 2 | |

facsimile, folio 13 | |

| Also known as | Llyfr Taliesin |

| Date | First half of the 14th century |

| Language(s) | Welsh |

| Size | 38 folios |

| Contents | Some 60 Welsh poems |

The volume contains some of the oldest poems in Welsh, possibly but not certainly dating back to the sixth century and to a real poet called Taliesin (though these, if genuine, would have been composed in the Cumbric dialect of Brittonic-speaking early medieval north Britain, being adapted to the Welsh dialect of Brittonic in the course of their transmission in Wales).

Date and provenance of the manuscript

editThe manuscript, known as Peniarth MS 2 and kept at the National Library of Wales, is incomplete, having lost a number of its original leaves including the first. It was named Llyfr Taliessin in the seventeenth century by Edward Lhuyd and hence is known in English as "The Book of Taliesin". The palaeographer John Gwenogvryn Evans dated the Book of Taliesin to around 1275, but Daniel Huws dated it to the first quarter of the fourteenth century, and the fourteenth-century dating is generally accepted.[1]: 164

The Book of Taliesin was one of the collection of manuscripts amassed at the mansion of Hengwrt, near Dolgellau, Gwynedd, by the Welsh antiquary Robert Vaughan (c. 1592–1667); the collection was eventually donated by Sir John Williams in 1907 to the newly established National Library of Wales as the Peniarth or Hengwrt-Peniarth Manuscripts.[2]

It appears that some "marks", presumably awarded for poems, measuring their "value", are extant in the margin of the Book of Taliesin.

Contents by topic

editTitles adapted from Skene.

Praise poems to Urien Rheged

edit- XXXI "Gwaeith Gwen ystrad" ("The Battle of Gwen ystrad")

- XXXII Urien Yrechwydd (A Song for Urien Rheged)

- XXXIII Eg gorffowys (A Song for Urien Rheged)

- XXXIV Bei Lleas Vryan (A Song for Urien Rheged)

- XXXV "Gweith Argoet Llwyfein"("The Battle of Argoed Llwyfain")

- XXXVI Arddwyre Reged (A Song for Urien Rheged)

- XXXVII "Yspeil Taliesin" ("The Spoils of Taliesin")

- XXXIX "Dadolwch Vryen" ("The Satisfaction of Urien")

Other praise-songs

edit- XII "Glaswawt Taliesin" ("The Praise of Taliesin")

- XIV "Kerd Veib am Llyr" ("Song Before the Sons of Llyr")

- XV "Kadeir Teyrnon" ("The Chair of the Sovereign")

- XVIII Kychwedyl am dodyw ("A rumour has come to me")

- XIX "Kanu y Med" ("Song of Mead")

- XX "Kanu y Cwrwf" ("Song of Ale")

- XXI "Etmic Dinbych" ("Praise of Tenby")

- XXIII "Trawsganu Kynon" ("Satire on Cynan Garwyn")

- XXV Torrit anuyndawl (Song of the Horses)

- XXXVIII Rhagoriaeth Gwallawc(Song on Gwallawg ab Lleenawg)

Elegies

edit- XL "Marwnat Erof" (Elegy of Erof [Ercwlf])

- XLI "Marwnat Madawg" (Elegy of Madawg)

- XLII "Marwnat Corroi ap Dayry" (Elegy of Cu-Roi son of Daire)

- XLIII "Marwnat Dylan eil Ton" (Elegy of Dylan son of the Wave)

- XLIV "Marwnat Owain ap Vryen" (Elegy of Owain son of Urien)

- XLV "Marwnat Aeddon" (Elegy of Aeddon)

- XLVI "Marwnat Cunedda" (Elegy of Cunedda)

- XLVIII "Marwnat Vthyr Pen" (Elegy of Uthyr Pen(dragon))

Hymns and Christian verse

edit- II Marwnat y Vil Veib ("Elegy of a Thousand Sons", a memoir of the saints)

- V Deus Duw ("O God, God of Formation", Of the Day of Judgment)

- XXII "Plaeu yr Reifft" ("The Plagues of Egypt", Mosaic history)

- XXIV Lath Moessen ("The Rod of Moses", Of Jesus)

- XXVI Y gofiessvys byt ("The Contrived World", Of Alexander)

- XXVII Ar clawr eluyd ("On the Face of the Earth", Of Jesus)

- XXVIII Ryfedaf na chiawr (Of Alexander the Great)

- XXIX Ad duw meidat ("God the Possessor", Hymn to the god of Moses, Israel, Alexander)

- LI Trindawt tragywyd ("The Eternal Trinity")

Prophetic

edit- VI "Armes Prydein Vawr" ("The Great Prophesy of Britain")

- X "Daronwy" ("Daronwy")

- XLVII "Armes Prydein Bychan" ("The Lesser Prophesy of Britain")

- XLIX Kein gyfedwch ("A bright festivity")

- LII "Gwawt Lud y Mawr" ("The Greater Praise of Lludd")

- LIII Yn wir dymbi romani kar ("Truly there will be to me a Roman friend")

- LIV "Ymarwar Llud Bychan" ("The Lesser Reconciliation of Lludd")

- LVII Darogan Katwal[adr?] ("Prophecy of Cadwallader" (title only))

Philosophic and gnomic

edit- I "Priv Cyfarch" ("Taliesin's First Address")

- III "Buarch Beird" ("The Fold of the Bards")

- IV "Aduvyneu Taliesin" ("The Pleasant Things of Taliesin")

- VII "Angar Kyfyndawt" ("The Loveless Confederacy")

- VIII "Kat Godeu" ("The Battle of the Trees")

- XI "Cadau Gwallawc" ("Song on Lleenawg")

- IX "Mab Gyrfeu Taliesin" ("The Childhood Achievements of Taliesin")

- XIII "Kadeir Taliesin" ("The Chair of Taliesin")

- XVI "Kadeir Kerrituen" ("The Chair of Cerridwen")

- XVII "Kanu Ygwynt" ("The Song of the Wind")

- XXX "Preiddeu Annwfn" ("The Spoils of Annwn")

- LV "Kanu y Byt Mawr" ("Great Song of the World")

- LVI "Kanu y Byt Bychan" ("Little Song of the World")

Date and provenance of contents

editMany of the poems have been dated to the twelfth and thirteenth centuries and are likely to be the work of poets adopting the Taliesin persona for the purposes of writing about awen (poetic inspiration), characterised by material such as:

- I have been a multitude of shapes,

- Before I assumed a consistent form.

- I have been a sword, narrow, variegated,

- I have been a tear in the air,

- I have been in the dullest of stars.

- I have been a word among letters,

- I have been a book in the origin.

A few are attributed internally to other poets. A full discussion of the provenance of each poem is included in the definitive editions of the book's contents poems by Marged Haycock.[3][page needed][4][page needed]

Canu Taliesin

editThe scholar Amy Mulligan states that only twelve of the poems, called the Canu Taliesin (song of Taliesin), mainly in praise of Urien, sixth century ruler of Rheged, "are accepted as canonical poems by a historical Taliesin".[5] Ifor Williams similarly describes the Canu Taliesin as credibly being the work of Taliesin, or at least 'to be contemporary with Cynan Garwyn, Urien, his son Owain, and Gwallawg', possibly historical kings who respectively ruled Powys; Rheged, which was centred in the region of the Solway Firth on the borders of present-day England and Scotland and stretched east to Catraeth (identified by most scholars as present-day Catterick in North Yorkshire) and west to Galloway; and Elmet.[6] These are (giving Skene's numbering used in the content list below in Roman numerals, the numbering of Evans's edition of the manuscript in Arabic, and the numbers and titles of Williams's edition in brackets):

| Numbering by | Williams's title (if any) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Skene | Evans | Williams | |

| XXIII | 45 | I | Trawsganu Kynan Garwyn Mab Brochfael |

| XXXI | 56 | II | |

| XXXII | 57 | III | |

| XXXIII | 58 | IV | |

| XXXIV | 59 | V | |

| XXXV | 60 | VI | Gweith Argoet Llwyfein |

| XXXVI | 61 | VII | |

| XXXVII | 62 | VIII | Yspeil Taliesin. Kanu Vryen |

| XXXIX | 65 | IX | Dadolwych Vryen |

| XLIV | 67 | X | Marwnat Owein |

| XI | 29 | XI | Gwallawc |

| XXXVIII | 63 | XII | Gwallawc |

Poems 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, and 9 (in Williams's numbering) close with the same words, suggesting common authorship, while 4 and 8 contain internal attributions to Taliesin. The closing tag runs

Ac yny vallwyf (i) ben |

Until I perish in old age, |

The precise dating of these poems remains uncertain. Re-examining the linguistic evidence for their early date, Patrick Sims-Williams concluded in 2016 that

evaluating the supposed proofs that poems in the Books of Aneirin and Taliesin cannot go back to the sixth century, we have found them either to be incorrect or to apply to only a very few lines or stanzas that may be explained as additions. It seems impossible to prove, however, that any poem must go back to the sixth century linguistically and cannot be a century or more later.[1]: 217

Scholarly English translations of all these are available in Poems from the book of Taliesin (1912) and the modern anthology The Triumph Tree.[8]

Later Old Welsh poems

editAmong probably less archaic but still early texts, the manuscript also preserves a few hymns, a small collection of elegies to famous men such as Cunedda and Dylan Eil Ton and also famous enigmatic poems such as The Battle of Trees, The Spoils of Annwfn (in which the poet claims to have sailed to another world with Arthur and his warriors), and the tenth-century prophetic poem Armes Prydein Vawr. Several of these contain internal claims to be the work of Taliesin, but cannot be associated with the putative historical figure.

Many poems in the collection allude to Christian and Latin texts as well as native British tradition, and the book contains the earliest mention in any Western post-classical vernacular literature of the feats of Hercules and Alexander the Great.

Scholarship and academic commentary

editTaliesin as shaman and shape-shifter

editThe introduction to Gwyneth Lewis and Rowan Williams's translation of The Book of Taliesin suggests that later Welsh writers came to see Taliesin as a sort of shamanic figure. The poetry ascribed to him in this collection shows how he can not only channel other entities himself (such as the Awen) in these poems, but that the authors of these poems can in turn channel Taliesin as they both create and perform the poems that they ascribe to Taliesin's persona. This creates a collectivist, rather than individualistic, sense of identity; no human is simply one human, humans are part of nature (rather than opposed to it), and all things in the cosmos can ultimately be seen to be connected through the creative spirit of the Awen. [9]

Editions and translations

editFacsimiles

edit- The Book of Taliesin at the National Library of Wales (colour images of Peniarth MS 2).

- Evans, J. Gwenogvryn, Facsimile and Text of the Book of Taliesin (Llanbedrog, 1910)

Editions and translations

edit- The Book of Taliesin: Poems of Warfare and Praise in an Enchanted Britain. Translated by Lewis, Gwyneth; Williams, Rowan. London: Penguin. 2019. ISBN 978-0-241-38113-7. Retrieved 17 May 2020. (complete translation)

- Evans, J. Gwenogvryn, Poems from the Book of Taliesin (Llanbedrog, 1915)

- Haycock, Marged, ed. (2007). Legendary Poems from the Book of Taliesin. CMCS Publications. Aberystwyth. ISBN 978-0-9527478-9-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - The Poems of Taliesin, ed. by Ifor Williams, trans. by J. E. Caerwyn Williams, Medieval and Modern Welsh Series, 3 (Dublin: The Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1968)

- The book of Taliesin, from the nineteenth-century translation by W.F. Skene

References

edit- ^ a b Sims-Williams, Patrick (30 September 2016). "Dating the Poems of Aneirin and Taliesin". Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie. 63 (1): 163–234. doi:10.1515/zcph-2016-0008. S2CID 164127245.

- ^ Jenkins, David (2002). A Refuge in Peace and War: The National Library of Wales to 1952. Aberystwyth: The National Library of Wales. pp. 99–111, 152–53. ISBN 1-86225-034-0.

- ^ Haycock, Marged (2007). Legendary Poems from The Book of Taliesin. Aberystwyth: CMCS.

- ^ Haycock, Marged (2013). Prophecies from The Book of Taliesin. Aberystwyth: CMCS.

- ^ Mulligan, Amy C. (2016). "Moses, Taliesin, and the Welsh Chosen People: Elis Gruffydd's Construction of a Biblical, British Past for Reformation Wales". Studies in Philology. 113 (4): 767–768.

- ^ Williams, Ifor, ed. (1968). The Poems of Taliesin. Medieval and Modern Welsh Series. Vol. 3. Translated by Williams, J. E. Caerwyn. Dublin: The Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. p. lxv.

- ^ Koch, John T., ed. (2005). "Taliesin I the Historical Taliesin". Celtic Culture. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. p. 1652.

- ^ Clancy, Thomas Owen, ed. (1998). The Triumph Tree; Scotland's Earliest Poetry, AD 550–1350. Edinburgh: Canongate. pp. 79–93.

- ^ Anonymous, trans. Gwyneth Lewis and Rowan Williams (2019). The Book of Taliesin: Poems of Warfare and Praise in an Enchanted Britain. London: Penguin Classics. pp. xxiii and following.

Further reading

edit- Meic Stephens, ed. (1998). "Book of Taliesin". The New Companion to the Literature of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 0-7083-1383-3.

- Haycock, Marged (1988). "Llyfr Taliesin". National Library of Wales Journal. 25: 357–86.

- Parry, Thomas (1955). A History of Welsh literature. H. Idris Bell (tr.). Oxford: Clarendon Press.