This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2020) |

In common law systems, land tenure, from the French verb "tenir" means "to hold", is the legal regime in which land "owned" by an individual is possessed by someone else who is said to "hold" the land, based on an agreement between both individuals.[1] It determines who can use land, for how long and under what conditions. Tenure may be based both on official laws and policies, and on informal local customs (insofar higher law does allow that). In other words, land tenure implies a system according to which land is held by an individual or the actual tiller of the land but this person does not have legal ownership. It determines the holder's rights and responsibilities in connection with their holding. The sovereign monarch, known in England as the Crown, held land in its own right. All land holders are either its tenants or sub-tenants. Tenure signifies a legal relationship between tenant and lord, arranging the duties and rights of tenant and lord in relationship to the land. Over history, many different forms of land tenure, i.e., ways of holding land, have been established.

A landowner is the holder of the estate in land with the most extensive and exclusive rights of ownership over the territory, simply put, the owner of land.

Feudal tenure

editThe legal concept of land tenure in the Middle Ages has become known as the feudal system that has been widely used throughout Europe, the Middle East and Asia Minor. The lords who received land directly from the Crown, or another landowner, in exchange for certain rights and obligations were called tenants-in-chief.

They doled out portions of their land to lesser tenants who in turn divided it among even lesser tenants. This process—that of granting subordinate tenancies—is known as subinfeudation. In this way, all individuals except the monarch did hold the land "of" someone else because legal ownership was with the (superior) monarch, also known as overlord or suzerain.[2][3]

Historically, it was usual for there to be reciprocal duties and rights between lord and tenant. There were different kinds of tenure to fit various kinds of need. For instance, a military tenure might be by knight-service, requiring the tenant to supply the lord with a number of armed horsemen and ground troops.

The fees were often lands, land revenue or revenue-producing real property, typically known as fiefs or fiefdoms.[4] Over the ages and depending on the region a broad variety of customs did develop based on the same legal principle.[5][6] The famous Magna Carta for instance was a legal contract based on the medieval system of land tenure.

The concept of tenure has since evolved into other forms, such as leases and estates.

Modes of ownership and tenure

editThere is a great variety of modes of land ownership and tenure.

Traditional land tenure

editMost of the indigenous nations or tribes of North America had differing notions of land ownership. Whereas European land ownership centered around control, Indigenous notions were based on stewardship. When Europeans first came to North America, they sometimes disregarded traditional land tenure and simply seized land, or they accommodated traditional land tenure by recognizing it as aboriginal title. This theory formed the basis for treaties with indigenous peoples.[citation needed]

Ownership of land by swearing to make productive use of it

editIn several developing countries, such as Egypt and Senegal, this method is still presently in use. In Senegal, it is mentioned as "mise en valeur des zones du terroir"[7] and in Egypt, it is called Wadaa al-yad.[8]

Allodial title

editAllodial title is a system in which real property is owned absolutely free and clear of any superior landlord or sovereign. True allodial title is rare, with most property ownership in the common law world (Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, United Kingdom, United States) being in fee simple. Allodial title is inalienable, in that it may be conveyed, devised, gifted, or mortgaged by the owner, but it may not be distressed and restrained for collection of taxes or private debts, or condemned (eminent domain) by the government.

Feudal land tenure

editFeudal land tenure is a system of mutual obligations under which a royal or noble personage granted a fiefdom — some degree of interest in the use or revenues of a given parcel of land — in exchange for a claim on services such as military service or simply maintenance of the land in which the lord continued to have an interest. This pattern obtained from the level of high nobility as vassals of a monarch down to lesser nobility whose only vassals were their serfs.

Fee simple

editUnder common law, Fee simple is the most complete ownership interest one can have in real property, other than the rare Allodial title. The holder can typically freely sell or otherwise transfer that interest or use it to secure a mortgage loan. This picture of "complete ownership" is, of course, complicated by the obligation in most places to pay a property tax and by the fact that if the land is mortgaged, there will be a claim on it in the form of a lien. In modern societies, this is the most common form of land ownership. Land can also be owned by more than one party and there are various concurrent estate rules.

Native title

editIn Australia, native title is a common law concept that recognizes that some indigenous people have certain land rights that derive from their traditional laws and customs.[9] Native title can co-exist with non-indigenous proprietary rights and in some cases different indigenous groups can exercise their native title over the same land. There are approximately 160 registered determinations of native title, spanning some 16% of Australia's land mass. The case of Mabo overturned the decision in Milirrpum and repudiated the notion of terra nullius. Subsequent Parliamentary Acts passed recognised the existence of this common law doctrine.

Life estate

editUnder common law, Life estate is an interest in real property that ends at death. The holder has the use of the land for life, but typically no ability to transfer that interest or to use it to secure a mortgage loan.

Fee tail

editUnder common law, fee tail is hereditary, non-transferable ownership of real property. A similar concept, the legitime, exists in civil and Roman law; the legitime limits the extent to which one may disinherit an heir.

Leasehold

editUnder both common law and civil law, land may be leased or rented by its owner to another party. A wide range of arrangements are possible, ranging from very short terms to the 99-year leases common in the United Kingdom for flats, and allowing various degrees of freedom in the use of the property.

Common land

editRights to use a common may include such rights as the use of a road or the right to graze one's animals on commonly owned land.

Sharecropping

editWhen sharecropping, one has use of agricultural land owned by another person in exchange for a share of the resulting crop or livestock.

Easement

editEasements allow one to make certain specific uses of land owned by someone else. The most classic easement is right-of-way (right to cross), but it could also include (for example) the right – known as a wayleave – to run an electrical power line across someone else's land.

Other

editIn addition, there are various forms of collective ownership, which typically take either the form of membership in a cooperative, or shares in a corporation, which owns the land (typically by fee simple, but possibly under other arrangements). There are also various hybrids; in many communist states, government ownership of most agricultural land has combined in various ways with tenure for farming collectives.

In archaeology

editIn archaeology, traditions of land tenure can be studied according to territoriality and through the ways in which people create and utilize landscape boundaries, both natural and constructed. Less tangible aspects of tenure are harder to qualify, and study of these relies heavily on either the anthropological record (in the case of pre-literate societies) or textual evidence (in the case of literate societies).

In archaeology, land tenure traditions can be studied across the longue durée, for example land tenure based on kinship and collective property management. This makes it possible to study the long-term consequences of change and development in land tenure systems and agricultural productivity.

Moreover, an archaeological approach to land tenure arrangements studies the temporal aspects of land governance, including their sometimes temporary, impermanent and negotiable aspects as well as uses of past forms of tenure. For example, people can lay claim to, or profess to own resources, through reference to ancestral memory within society. In these cases, the nature of and relationships with aspects of the past, both tangible (e.g. monuments) and intangible (e.g. concepts of history through story telling) are used to legitimize the present.

By country

editAngola

editAfghanistan

edit41 of the Constitution of Afghanistan, foreigners are not allowed to own land. Foreign individuals shall not have the right to own immovable property in Afghanistan[10][11][12]

Canada

editChina

editLand in China is state-owned or collectively owned. Enterprises, farmers, and householders lease land from the state using long-term leases of 20 to 70 years.[13] Foreign investors are not allowed to buy or own land in China.

Thailand

editIn Thailand foreigners are normally prohibited to own or possess land in Thailand. These restrictions are covered in the land code, articles 96 and following.

Cambodia

editUnder Article 44 of the Cambodian Constitution, "only natural persons or legal entities of Khmer nationality shall have the right to land ownership." foreigners are prohibited to own or possess land in Cambodia.[14][15]

Philippines

editForeigners are prohibited owning land in the Philippines under the 1987 Constitution.[16][17]

Indonesia

editForeigners are not allowed to own freehold land in Indonesia.[18][19]

Vietnam

editForeigners cannot buy and own land, like in many other Southeast Asian countries. Instead, the land is collectively owned by all Vietnamese people, but governed by the state. As written in the national Land Law, foreigners and foreign organizations are allowed to lease land. The leasehold period is up to 50 years.[20][21]

Burma

editThough purchase of land is not permitted to foreigners, a real estate investor may apply for a 70 year leasehold with a Myanmar Investment Commission (MIC) permit.[22]

Belarus

editAccording to the legislation of Belarus, a foreign citizen cannot own land and only has the right to rent it.[23][24]

Laos

editAs foreigners are prohibited from permanent ownership of land. Foreigners can only lease land for a period of up to 30 year.[25][26]

Mongolia

editOnly Mongolian citizens can own the land within the territory of Mongolia. foreign citizens can only lease the land.[27][28][29]

Maldives

editForeigners are not allowed to own freehold land in Maldives. the land can only be leased to foreigners for 99 years.[30][31]

Sri Lanka

editIn 2014, the Sri Lankan parliament passed a law banning land purchases by foreigners. The new act will allow foreigners to acquire land only on a lease basis of up to 99 years with an annual 15 percent tax on the total rental paid upfront.[32][33][34][35]

Georgia

editSince 2017, A ban on foreigners owning farmland was introduced in the Georgia's new constitution. The new constitution states that, with a small number of exceptions, agricultural land can only be owned by the state, a Georgian citizen or a Georgian-owned entity.[36][37][38][39]

Kazakhstan

editIn 2021, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev signed into law a bill that bans the selling and leasing of agricultural land to foreigners.[40][41][42]

Israel

editApproximately 7% of the allocated land in Israel is privately owned. The rest, i.e. 93%, is owned by the State and is known as "Israeli Land". Israel's Basic Law on real estate states that Israel's Land is jointly owned by the State (69%), the Development Authority (12%), and the Jewish National Fund (12%).

Ireland

edit- Land and Conveyancing Law Reform Bill, 2006[43]

United Kingdom

editEngland and Wales

editScotland

editUnited States

editImportance of tenure today

editWith homelessness and wealth inequality on the rise, land tenure in the developed world has become a point of issue.[44][45] Market-based economies which treat housing as a commodity and not a right allow for laws such as California Proposition 13 (1978) that incentivize treating housing as an investment.[46][47] Due to inelastic demand of the human need for shelter, housing prices can therefore be raised above universally-affordable rates.[48][49] This complicates tenure by limiting supply and exacerbating homelessness and informal housing arrangements.[50] For instance, in the United States, minimal regulation on house flipping and rent-seeking behavior allows for gentrification, pricing out half a million Americans and leaving them homeless.[51] This is in light of 17 million homes left vacant as investment vehicles of the wealthy.[52]

At the same time, severe weather events caused by climate-change have become more frequent, affecting property values.[53]

In the developing world, catastrophes are impacting greater numbers of people due to urbanization, crowding, and weak tenure and legal systems.

Colonial land-tenure systems have led to issues in post-colonial societies.[54]

The concepts of "landlord" and "tenant" have been recycled to refer to the modern relationship of the parties to land which is held under a lease. Professor F.H. Lawson in Introduction to the Laws of Property (1958) has pointed out, however, that the landlord-tenant relationship never really fitted in the feudal system and was rather an "alien commercial element".

The doctrine of tenure did not apply to personalty (personal property). However, the relationship of bailment in the case of chattels closely resembles the landlord-tenant relationship that can be created in land.

Secure land-tenure also recognizes one's legal residential status in urban areas and it is a key characteristic in slums. Slum-dwellers do not have legal title to the land and thus local governments usually marginalize and ignored them.[55]

In 2012, the Committee on World Food Security based at the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, endorsed the Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure as the global norm, as the problem of poor and politically marginalized especially likely to suffer from insecure tenure, however, this is merely work in progress. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 5 also advocates for reforms to give women access to ownership and control over land in recognition of the importance of tenure to resource distribution.[56]

See also

edit- Alienated land – land acquired from customary landowners by government

- Allodial title – Ownership of real property that is independent of any superior landlord

- Apertura feudi – Loss of a feudal land tenure

- Concentration of land ownership – Ownership of land in a particular area by a small number of people or organizations

- Development easement

- Eminent domain – Legal power of a government to take private property for public use

- Feudalism – Legal and military structure in medieval Europe

- Fiefdom – Right granted by overlord to vassal, central element of feudalism

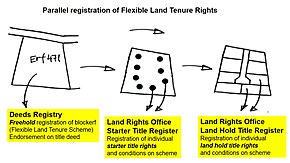

- Flexible Land Tenure System (Namibia) – concept to provide affordable security of tenure to inhabitants in informal settlements in Namibia

- History of English land law – Law of real property in England

- Homestead principle – Legal principle regarding unclaimed natural resources

- Land (economics) – Use of land as capital for production

- Land administration – way in which the rules of Land tenure are applied and made operational

- Land grabbing – Large-scale acquisition of land (over 1,000 ha) whether by purchase, leases or other means.

- Landed gentry – British and Irish social class of wealthy land owners

- Landed nobility – Nobility privileged with landownership

- Landed property – Income-generating land owned by gentry

- Land reform – Changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership

- Land titling – Assignment of land ownership to its occupants

- Land trust – Conservation organization

- Lord paramount – Feudal overlord: a lord with no obligations to a higher lord

- Manorialism – Economic, political, and judicial institution during the Middle Ages in Europe

- Mesne lord – Type of lord in the feudal system

- Open field system – Prevalent ownership and land use structure in medieval agriculture

- Possession (law) – Control a person intentionally exercises towards a thing

- Precaria – Form of land tenure

- Quia Emptores – English statute of 1290

- Rights and Resources Initiative – International non-governmental organization focused on land and forest rights

- Squatting – Unauthorized occupation of property

- Tenement (law) – The holder of a legal interest in real estate

- Title (property) – Bundle of rights to a property

- Usucaption – Acquisition of property

References

edit- ^ "What is Land Tenure?". LandLinks. Retrieved 2023-07-28.

- ^ "Overlord". Wordnik. Retrieved 2022-11-14.

- ^ "Suzerain". Merriam Webster.

- ^ "fief | Definition, Size, & Examples". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-04-03.

- ^ Elizabeth A.R. Brown. "Feudalism". Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- ^ Reynolds, Susan (Wikipedia article Susan Reynolds) (1994). Fiefs and Vassals: The Medieval Evidence Reinterpreted. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- ^ "Till to Tiller: Linkages between international remittances and access to land in West Africa". www.fao.org. Retrieved 2017-07-19.

- ^ "National Geographic Magazine – NGM.com". ngm.nationalgeographic.com. Archived from the original on February 25, 2009. Retrieved 2017-07-19.

- ^ "Exactly what is native title? - What is native title? - National Native Title Tribunal". Archived from the original on 2010-06-23. Retrieved 2010-06-23.

- ^ Thompson, Tres; Darby, Marta; Hillenbrand, Michelle; Kempner, Trevor; Kothari, Mansi; Lawrence, Andrew; Nelson, Ryan; Wakefield, Tom (2015). AN INTRODUCTION TO THE PROPERTY LAW OF AFGHANISTAN (PDF). Palo Alto, California: Stanford Law School. p. 10:

consider Article 41 of the Constitution: "Foreign individuals shall not have the right to own immovable property in Afghanistan.

- ^

Amir Zeb Khan (2009). Extraction of Parcel Boundaries from Ortho-rectified Aerial Photos: A cost effective technique (PDF) (Report). International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. p. 2. 112. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

As per article Forty-one Ch. 2, of the constitution foreign persons do not have the right to own immovable property in Afghanistan.

- ^ "Afghanistan's Constitution of 2004" (PDF). www.constituteproject.org. Pakistan. 6 July 2023 [26 January 2004]. p. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ Stuart Leavenworth and Kiki Zhao (May 31, 2016). "In China, Homeowners Find Themselves in a Land of Doubt". The New York Times. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

All land in China is owned by the government, which parcels it out to developers and homeowners through 20- to 70-year leases.

- ^ "Can Foreigners Own Land in Cambodia? Here's How". October 2020.

- ^ "Can foreigners buy real estate in Cambodia? The 4 titles you must know". 16 September 2020.

- ^ "Can foreigners own land in the Philippines?". Manila Standard.

- ^ "Real estate regulations in the Philippines". 7 April 2016.

- ^ "Buying Property in Indonesia | How to Buy a House in Indonesia". 19 October 2018.

- ^ "Understanding law & regulations before buying land & properties in Bali (2023)". 23 November 2023.

- ^ "Can foreigner buy property in Vietnam?". 12 September 2019.

- ^ "How to Buy Property in Vietnam: The Ultimate Guide". 30 January 2019.

- ^ "Buying property in Myanmar". 21 March 2017.

- ^ "How can a foreigner buy property in Belarus". Legal Office "Leshchynski Smolski".

- ^ "Property in Belarus | Belarusian Real Estate Investment".

- ^ "Laos Opens Real Estate Investment Opportunities to Foreigners". 15 October 2020.

- ^ "Want to Invest in Laos? Here's Why You Shouldn't". 10 August 2017.

- ^ "Land Law of Mongolia".

- ^ "Buying property in Mongolia". March 2017.

- ^ "FAQs". 10 October 2015.

- ^ "Maldives parliament repeals law allowing foreign land ownership". Reuters. 18 April 2019.

- ^ "Maldives parliament repeals law allowing foreign land ownership - ET RealEstate".

- ^ "Sri Lanka enacts ban on foreigners buying land". Reuters. 2014-10-21. Retrieved 2022-02-16.

- ^ "Sri Lanka passes law banning sale of land to foreign citizens | Tamil Guardian". www.tamilguardian.com. Retrieved 2022-02-16.

- ^ "Citizen or Not: The Process and Concerns of Buying Property in Sri Lanka as an Expat". CeylonToday. Retrieved 2022-02-16.

- ^ "A guide for foreigners wanting to buy real estate in Sri Lanka". The New Sri Lankan House. Retrieved 2022-02-16.

- ^ "Georgia's ban on foreign landowners leaves farmers in limbo". Reuters. 17 April 2019.

- ^ "Georgia Keeping Its Land Off-Limits for Foreigners | Eurasianet".

- ^ "Land reform - land settlement and cooperatives - Special Edition".

- ^ "Georgia temporarily lifts ban on sale of agricultural land to foreign citizens". 7 December 2018.

- ^ "Kazakh President Signs into Law Long-Debated Bill Banning Land Ownership by Foreigners". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 13 May 2021.

- ^ "Kazakhstan Bans Sale of Agricultural Lands to Foreigners".

- ^ "Kazakh president orders ban on foreign ownership of farmland". Reuters. 25 February 2021.

- ^ "Land and Conveyancing Law Reform Act 2009 – No. 27 of 2009 – Houses of the Oireachtas" (PDF). 2006-06-07.

- ^ "HUD Releases 2020 Annual Homeless Assessment Report Part 1". HUD.gov / U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). 2021-03-17. Retrieved 2022-02-20.

- ^ "The World #InequalityReport 2022 presents the most up-to-date & complete data on inequality worldwide". World Inequality Report 2022 (in French). Retrieved 2022-02-20.

- ^ "Inside the Commodification of Residential Real Estate". The Real Deal New York. Retrieved 2022-02-20.

- ^ Ferrer, Alexander. "The Real Problem With Corporate Landlords". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2022-02-20.

- ^ "Tenant Rights". HUD.gov / U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). 20 September 2017. Retrieved 2022-02-20.

- ^ Tars, Eric. "Housing as a Human Right" (PDF). National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty.

- ^ "Naming Housing as a Human Right Is a First Step to Solving the Housing Crisis". Housing Matters. 2021-12-08. Retrieved 2022-02-20.

- ^ "Tenant Rights". HUD.gov / U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). 20 September 2017. Retrieved 2022-02-20.

- ^ "Homelessness & Empty Homes: Trends Since 2010 | Self". www.self.inc. Retrieved 2022-02-20.

- ^ "The Devastating Effects of Climate Change on US Housing Security". The Aspen Institute. 2021-04-09. Retrieved 2022-02-20.

- ^

For example:

Leonard, Rebeca; Longbottom, Judy, eds. (2000). "Colonial land tenure system - Droit foncier colonial". Land Tenure Lexicon: A Glossary of Terms from English and French Speaking West Africa. London: International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED). p. 14. ISBN 9781899825462. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

[...] throughout West Africa, because of the great difficulties in enforcing land law, decisions about land claims have more often reflected the power and influence of the different stakeholders, rather than enforcing the letter of the law [...].

- ^ Field, E. (2005). "Property rights and investment in urban slums". Journal of the European Economic Association. 3 (2–3): 279–290. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.576.1330. doi:10.1162/jeea.2005.3.2-3.279.

- ^ "Sustainable Development Goal 5: Gender equality". UN Women. Retrieved 2020-09-23.

Further reading

edit- John Baker, An Introduction to English Legal History (3rd edition) 1990 Butterworths. ISBN 0-406-53101-3

External links

edit- Media related to Land tenure at Wikimedia Commons