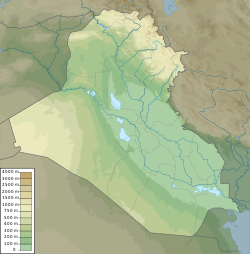

Shaduppum, modern Tell Harmal (also Tell Abu Harmal), is an archaeological site in Baghdad Governorate (Iraq). Nowadays, it lies within the borders of modern Baghdad about 600 meters from the site of Tell Mohammad (possibly ancient Diniktum). In the Old Babylonian period it was part of the kingdom of Eshnunna. Other cities in the kingdom lie not far away including Eshnunna (30 miles to the southwest) and Tell Ishchali and Khafajah four and six miles away on the left bank of the Diyala River. The site of Tell al-Dhiba'i, thought to be the ancient town of Uzarzalulu, is about 2 kilometers away and of similar characteristics.[1]

Shaduppum | |

| Location | Baghdad, Baghdad Governorate, Iraq |

|---|---|

| Region | Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 33°18′34.1388″N 44°28′01.4340″E / 33.309483000°N 44.467065000°E |

| Type | tell |

| History | |

| Periods | Old Babylonian |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1945–1949, 1997–1998 |

| Archaeologists | Taha Baqir, Sayid Muhammed Ali Mustafa, P. Miglus, L. Hussein |

Archaeology

editThe site, 150 meters in diameter and 5 meters high. Tell Harmal consists of a heavily fortified irregular rectangle (147 x 133 x 146 x 97 meters). The fortification wall had a towered gateway in the northeast and had 6 meter wide buttresses. It was excavated by Iraqi archaeologists Taha Baqir and Sayid Muhammed Ali Mustafa of the Department of Antiquities and Heritage from 1945 to 1949 in response to planned residential development and illegal digging, discovering about 2000 unbaked clay cuneiform tablets. These tablets were found in both religious and administrative contexts. Stories about Creation, the flood, The epic of Gilgamesh, and other were inscribed on some of the tablets. Over 100 large (3.5 cm in diameter) pierced clay balls inscribed with daily brick making receipts were also found.[2][3][4] In 1997 and 1998, the site was worked by a team from Baghdad University and the German Archaeological Institute led by Peter Miglus and Laith Hussein.[5][6] Many other illegally excavated tablets have found their way into various institutions.

The site contains five occupation layers. The most recent (Layer 1) is fairly rudimentary and thought to be from Kassite times. Layer II contains more substantial construction and was where most of the cuneiform tablets were found. It dates to the reigns of Eshnunna rulers like Dadusha (c. 1800–1779 BC) and Ibal-pi-el II (c. 1779–1765 BC). This layer was destroyed by fire, thought to be by Hammurabi when he captured the city in his 31 year. Layer III has largely the same building plan and is marked by the construction of the fortification wall. It dates to the earlier reigns of Ipiq-Adad II, who drove the Elamites from the land, Ibal-pi-El I, Belakum, and Naram-Suen of Eshnunna. Layer IV contains the date fourmula of several rulers not previously known like Ammi-dashur. It corresponds to the time of Sumu-la-El (c. 1880–1845 BC) ruler of Babylon. Only dates of Ammi-dashur and the unknown ruler Iadkur-El were found in Layer V.[7][8] A deeper level of occupation (Layers IV and V) was reached only in soundings and dated as far back as the Akkadian Empire days.[2]

History

editNot much is known outside the Old Babylonian times, though clearly the location was occupied from at least the Akkadian period through the Old Babylonian period, when it was part of the kingdom of Eshnunna in the Diyala River area. It was an administrative center for the kingdom and its name means "the treasury."[9][10]

The site featured a large trapezoidal wall and a temple (28 x 18 meters in size)possibly of the goddess Nisaba and her consort Haya (called Khani by the excavators), a smaller (15 x 14 meters in size) (double shrine temple, and a large (23 x 23 meters in size) administrative building.[11] Among the tablets from Tell Harmal are two of the epic of Gilgamesh and two with parts of the Laws of Eshnunna, found in the context of ruler Dadusha.[12][13] Also found were a number of important mathematical tablets.[14][15][16][17] It also produced tablets with the longest list of geographical names yet known.[18]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ [1] Matoušová-Rajmova, Maria, "Some Cylinder Seals from Dhiba’i and Harmal", Sumer, vol. 31, iss. 1-2, pp. 49-66, 1975

- ^ a b [2] Taha Baqir, "Excavations at Tell Harmal II: Tell Harmal, A Preliminary Report, Sumer 2, iss. 2, pp. 22-30, 1946

- ^ [3] Taha Baqir, "Excavations at Harmal", Sumer, vol. 4, iss. 2, pp 137-39, 1948

- ^ Taha Baqir, "Tell Harmal", The Republic of Iraq Directorate of Antiquities, Baġdād Ar-Rabita Press, 1959

- ^ Laith M. Hussein and Peter A. Miglus, "Tell Harmal. Die Frühjahrskampagne 1997", Baghdader Mitteilungen, vol. 29, pp 35-46, 1998

- ^ Laith M. Hussein and Peter A. Miglus, "Tall Harmal. Die Herbstkampagne 1998", Baghdader Mitteilungen, vol. 30, pp 101-113, 1999

- ^ [4] Al-Hashimi, R., "New light on the date of Harmal and Dhiba’i’", Sumer, vol. 28, iss. 1-2, pp. 29-33, 1972

- ^ [5] Taha Baqir, "Date-Formulae and Date-Lists from Harmal", Sumer, vol. 5, iss. 1, pp 34-86, 1949

- ^ [6] Hussein, L. M., "Excavations in Tell Harmal: spring 1997", Sumer, vol. 50, iss. 1, pp. 58-67, 1999 (in arabic)

- ^ Hussein, L. M., "Excavations in Tell Harmal: Fall 1998", Sumer, vol. 51, pp. 114-122, 2001

- ^ [7] Seton Lloyd, "Excavations; Tell Harmal", Sumer, vol. 2, iss. 1. pp 13-15, 1945

- ^ [8] Taha Baqir, "A New Law-code from Tell Harmal", Sumer, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 52-53, Jan 1948

- ^ [9] Albrecht Goetze, "Another Law Tablet from Tell Harmal", Sumer, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 55, Jan 1948

- ^ [10] T. Baqir, "An important mathematical problem text from Tell Harmal (on a Euclidean Problem)", Sumer, vol. 6, iss. 1, pp. 39–54, 1950

- ^ T. Baqir, "Mathematical", Sumer, vol. 6, iss. 1 (Arabic), pp. 5–28, 1950

- ^ [11] T. Baqir, "Another important mathematical text from Tell Harmal", Sumer, vol. 6, iss. 2, pp. 130–148, 1950

- ^ [12] T Baqir, "Some more mathematical texts from Tell Harmal", Sumer, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 28–45, 1951

- ^ [13] Levy, Selim J., "Harmal Geographical List", Sumer, vol. 3, iss. 2, pp. 50-83, 1947

Further reading

edit- [14] Taha Baqir, "Supplement to the Date-Formulae from Harmal", Sumer, vol 5, iss. 5, pp 136–144, 1949

- [15] Bruins, E. M., "Comments on the mathematical tablets of Tell Harmal", Sumer, vol. 7, iss. 2, pp. 179–182, 1951

- [16] Bruins, Evert M., "Revision of the mathematical texts from Tell Harmal", Sumer, vol. 9, iss. 2, pp. 241–253, 1953

- [17] Drenckhahn, Friedrich, "A geometrical contribution to the study of the mathematical problem text from Tell Harmal (IM. 55357) in the Iraq Museum, Baghdad", Sumer, vol. 7, iss. 1, pp. 22–27, 1951

- Maria de J. Ellis, "Old Babylonian Economic Texts and Letters from Tell Harmal", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 43–69, 1972

- Maria de J. Ellis, "The Division of Property at Tell Harma"l, Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 133–153, 1974

- Maria de J. Ellis, "An Old Babylonian Adoption Contract from Tell Harmal", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 130–151, 1975

- [18] Friberg, Jöran, et al. "Five Texts from Old Babylonian Mê-Turran (Tell Haddad), Ishchali and Shaduppûm (Tell Harmal) with Rectangular-Linear Problems for Figures of a Given Form", New Mathematical Cuneiform Texts, pp. 149–212, 2016

- [19] A. Goetze, "A mathematical compendium from Tell Harmal", Sumer, vol. 7, iss. 2, pp. 126–155, 1951

- [20] Goetze, Albrecht, "Fifty Old-Babylonian Letters from Harmal", Sumer, vol. 14, iss. 1–2, pp. 3–78, 1958

- Gonçalves, Carlos. Mathematical Tablets from Tell Harmal. New York: Springer, 2015 ISBN 978-3-319-22523-4

- Hussein, Laith M. "Tell Harmal-Die Texte aus dem Hauptverwaltungsgebäude", Serai, 2006

- Grandpierre, Véronique, "Shaduppum (Tell Harnal): une petite ville du royaume d'Eshnunna au XVIIIe siècle avant notre ère", Doctoral Dissertation, Paris 1, 1998

- Simmons, Stephen D., "Early Old Babylonian Tablets from Ḥarmal and Elsewhere", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 71–93, 1959

- Lamia al-Gailani Werr, "A Note on the Seal Impression IM 52599 from Tell Harmal", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 62–64, 1978