Aliaga, officially the Municipality of Aliaga (Tagalog: Bayan ng Aliaga, Ilocano: Ili ti Aliaga), is a municipality in the province of Nueva Ecija, Philippines. According to the 2020 census, it has a population of 70,363 people.[3]

Aliaga | |

|---|---|

| Municipality of Aliaga | |

Municipal Hall | |

Map of Nueva Ecija with Aliaga highlighted | |

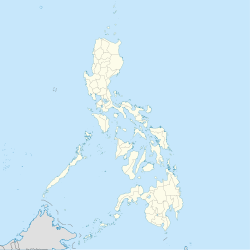

Location within the Philippines | |

| Coordinates: 15°30′13″N 120°50′42″E / 15.5036°N 120.845°E | |

| Country | Philippines |

| Region | Central Luzon |

| Province | Nueva Ecija |

| District | 1st district |

| Founded | 1849 |

| Named for | Aliaga, Spain |

| Barangays | 26 (see Barangays) |

| Government | |

| • Type | Sangguniang Bayan |

| • Mayor | Gilbert Moreno |

| • Vice Mayor | Erwin Dyan D. Javaluyas |

| • Representative | Estrellita B. Suansing |

| • Municipal Council | Members |

| • Electorate | 49,634 voters (2022) |

| Area | |

• Total | 90.04 km2 (34.76 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 26 m (85 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 43 m (141 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 19 m (62 ft) |

| Population (2020 census)[3] | |

• Total | 70,363 |

| • Density | 780/km2 (2,000/sq mi) |

| • Households | 16,853 |

| Demonyms | Aliagueño (Male), Aliagueña (Female), Aliaguenean |

| Economy | |

| • Income class | 2nd municipal income class |

| • Poverty incidence | 13.79 |

| • Revenue | ₱ 190.7 million (2020), 88.41 million (2012), 95.12 million (2013), 103.7 million (2014), 115.6 million (2015), 125 million (2016), 151 million (2017), 159.2 million (2018), 170 million (2019), 206.7 million (2021), 278.8 million (2022) |

| • Assets | ₱ 823.9 million (2020), 234.5 million (2012), 281.1 million (2013), 300 million (2014), 334.4 million (2015), 390.6 million (2016), 496.1 million (2017), 558.5 million (2018), 698.9 million (2019), 938.8 million (2021), 1,007 million (2022) |

| • Expenditure | ₱ 131.1 million (2020), 53.76 million (2012), 64.6 million (2013), 68.08 million (2014), 97.61 million (2015), 91.8 million (2016), 151 million (2017), 159.2 million (2018), 108.2 million (2019), 113.3 million (2021), 203.5 million (2022) |

| • Liabilities | ₱ 246.9 million (2020), 139.2 million (2012), 176.9 million (2013), 168.6 million (2014), 200.8 million (2015), 222.8 million (2016), 223.1 million (2017), 194.5 million (2018), 216.3 million (2019), 255.1 million (2021), 331.3 million (2022) |

| Service provider | |

| • Electricity | Nueva Ecija 2 Area 1 Electric Cooperative (NEECO 2 A1) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (PST) |

| ZIP code | 3111 |

| PSGC | |

| IDD : area code | +63 (0)44 |

| Native languages | Tagalog Ilocano |

| Website | www |

History

editThe town of Aliaga, Nueva Ecija was founded on January 3, 1849. This is much earlier than the traditionally commemorated date of February 8, 1849. This historical correction springs from a 2023 archival research. The research finds solid backing from pertinent 1849 records found at the Archdiocesan Archives of Manila. More importantly, the same date is inscribed clearly in the Decree of Establishment of the Aliaga Parish, also found at the Archdiocesan Archives. Additionally, these newly revisited records indicate that the canonical establishment of the Aliaga Parish took place on February 27, 1849, instead of April 26, 1849.

More significantly, the research also supplies the correct name of Aliaga's first Gobernadorcillo (town mayor): Aniceto Maria Muñoz. Previous documents have introduced him as Aniceto Ferry. The birth record of Don Aniceto Maria Muñoz reveals that his family hailed from Los Navalucillos in Toledo, Spain. This corrects an earlier misattribution, claiming that the gentleman came from the Spanish town of Aliaga.

In eastern Spain, Aliaga is a municipality located in the province of Teruel. Teruel is bordered by the provinces of Tarragona, Catellon, Valencia, Cuenca, Guadalajara, and Zaragoza. Aragon is an Autonomous Community, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. It comprises three provinces: Huesca, Zaragoza, and Teruel, with Zaragoza as its capital.

Looking back at how towns were established in the Spanish colony of the Philippines, the research team surmises that the local name Aliaga recalls the Spanish town intimately known to Don Aniceto. Other than Aliaga, familiar place names which had been taken from Spain include Jaen, Talavera, and Zaragoza. Thousands of miles away, in the Spanish colony of the Philippines, these towns quietly found their counterpart territories, next to Aliaga, all of them situated in the province of Nueva Ecija, Philippines.

Aliaga's first gobernadorcillo

editDon Aniceto Maria Muñoz y Ramos was born on March 30, 1813, in the town of Los Navalucillos in Toledo, Spain (Quiñones 2022). His parents were Segundo Muñoz and Dorotea Ramos, both natives of Los Navalucillos. He married Doña Clementina Leonor Marti y Arnedo who was born on April 18, 1842. Her parents were Jose Marti and Josefa Arnedo, from Alpera in La Mancha. The couple were married on July 31, 1863. The chronology suggests a wide age gap between the couple: Don Aniceto was already 50 years old when he married his 21-year old bride.

Don Aniceto was a lawyer by profession, a proprietor, and Alcalde Mayor (Governor) of Nueva Ecija. Archival documents kept in Talavera, Nueva Ecija show that on August 31, 1852, he presented a petition to the Governor General in Intramuros, creating Catuguian (later known as Talavera) as yet another town of Nueva Ecija.

Don Aniceto was Aliaga's first town mayor. He held this post in 1849, 1855, and 1859. At the age of 67, he died from a stroke back in his homeland on December 31, 1880.

Catholic heritage

editThe barrio of Bibiclat was established earlier than Aliaga. This barrio came into being in 1836, 13 years before Aliaga gained township. This information is the fruit of Isidro Gregorio's historical research, as one of Aliaga's dedicated historians. However, it is not until 1889 when Bibiclat would officially gain the name Barrio San Juan Bautista (Villamayor 2021).

Today, Bibiclat enjoys national fame for one unique tradition, carried out by devotees of its patron saint, San Juan Bautista. During the feast day of their patron saint, devout residents would dress up as “Taong Putik” (Mud People). Another way in which the faithful understand the ritual is to call it as “Pagsa-San Juan”—a mimetic gesture of assuming the character of St. John himself, negotiating the biblical wilderness.

Days before the great feast, the devotees would spend time fashioning their ritual cloak, usually made of vines or dried banana leaves. First, these are soaked in mud, even as the devotees themselves roll in the mud. Instead of a procession, the costumed devotees would ply the streets, begging for alms. At the conclusion of this ritual, they would spend whatever they had received, buying candles which would eventually be lit in church.

Since 1632, the municipality of Los Navalucillos in Spain has held a devotion, lighting votive candles to the Nuestra Señora La Virgen De Las Saleras. On September 8 each year, Don Aniceto's hometown would hold a fiesta lauding Our Lady of Salt. The celebration would include competitions, processions, cabezudos, and fireworks (Saleras Fiesta 2022).

The association with salt may be because Aliaga is located in an area consisting of a group of mines, because of sedimentary rocks still intact from the Cretaceous, Jurassic, and Tertiary Ages. The mine area is known for lignite, a type of brown coal used to generate electricity.

This region is called Cuencas Mineras, situated north of the province of Teruel. This geo-tourism paradise projects a strong and deep-rooted mining identity. For this reason, Aliaga holds the national record for developing Spain's first geological park. The Geological Park of Aliaga boasts of rock formations almost unique in the world, with layers stacked one on top of the other. Yet while Aliaga shines because of this group of famous rock mines, it does not have a salt mine. It may have lignite and coal to offer in abundance but not a grain of salt.

Another possible explanation for the association with the biblical image of salt are based on Don Aniceto's hometown of Los Navalucillos.

For this town, history declares that until the middle of the 18th century, the faithful continued to address their beloved patroness as Our Lady of Grace. Over time, though, this old and sacred name would gradually fade, in favor of a new one. Following lore, the residents gradually began hailing the Virgin as Nuestra Señora de Las Saleras. To this very day, believers repeat the beguiling story about the Virgin appearing to a shepherd, enabling him to give salt to his famished flock. This apparition has inspired a deep-rooted custom in the area which compensates for the deficient supply of salt in the pastures.

Don Aniceto was the moving force in selecting the Nuestra Señora La Virgen de las Saleras of his birthplace as the town's patron saint. However, Aliaga's patron saint enjoys a different feast day, celebrated annually on 26 April.

The parish of Nuestra Señora De Las Saleras in Aliaga was long thought to have been founded on April 26, 1849. However, historical records indicate the actual founding date was February 27, 1849. This discrepancy has led to the question: Why is the feast of Nuestra Señora De Las Saleras celebrated on April 26?

The name of Nuestra Señora De Las Saleras came to be officially associated with the parish only in the late 1880s, notably, after the parish had to be rebuilt following a devastating typhoon on September 17, 1887. The Augustinian Friars, who were overseeing the parish, chose April 26 as the feast day in honor of the Feast of the Mother of Good Counsel, a significant day for the Augustinian Order.

They likely intended for the Mother of Good Counsel, whom they deeply revered, to be recognized, too, as Nuestra Señora De Las Saleras, thus offering her protection and guidance to the parish from 1887 onwards. This decision would align the parish's celebration with an existing Augustinian tradition, giving the parish a renewed spiritual focus after the destruction it had endured.

There is an important hermitage in the square called “Ermita de Nuestra Señora de las Saleras”. It was inaugurated on April 14, 1632, centuries before Don Aniceto was born. Within walking distance, one can find the Plaza Mayor and the Oficina de Correos, or the post office. The temple has a Renaissance look to it, its interior tracing the shape of a Latin cross. At 120 square meters, the church of Don Aniceto's childhood has undergone several renovations over time.

Like the parish of San Sebastian in Los Navalucillos, the hermitage sustained extensive damage from the furious fires of the Civil War. For three years, from 1936 to 1939, it was converted into a school. Back then, a wall of the central nave was demolished to create large windows. It would take until 1943 for the nave's original features to be restored.

Fronting the church is a double-leaf wooden door installed in 1963. There is a small transept in the center which contains an altarpiece from the late 17th century. At its helm stands the figure of the Patroness of Los Navalucillos, venerated as the Virgen de las Saleras. Inside the temple, fresco paintings adorn the dome. These were made in 1822, reflecting allegorical moments in the life of the Virgin Mother.

The altar features a modest monstrance displaying the original head of the Virgen de las Saleras. The venerated image of the patroness shows the Virgin gazing upon her little shepherd and his goats being nurtured with salt. This statue plies the streets of the town during the annual procession on September 8.

Left of the temple hangs a copy of El Greco's painting, depicting the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian. Since March 2013, the faithful have maintained a devotion, praying to an image of the crucified Christ, through a generous donation from the Bravo Caballero family. They call this image the “Christ of Faith”. This Christ is framed and located to the right of the nave, visible as soon as you enter the temple.

In the Philippines, certain Marian images that were carved locally provide evidence about the creation of Nuestra Señora De Las Saleras. These Marian images include Our Lady of Orani in Bataan and Our Lady of Amorseco in San Fernando, Pampanga. Like Nuestra Señora De Las Saleras, these images enjoy a strong wave of devotion in their local areas. However, such devotion did not spread to other parts of the country the way popular devotions have surged, in honor of the Santo Nino (the Infant Jesus), the Nazareno (Black Nazarene), and some other Marian images.

Aliaga, Nueva Ecija is the lone Catholic parish featuring Our Lady of Las Saleras as its patroness. No other parish in the country has sustained a devotion to the Blessed Mother as Our Lady of Salt. The only other known visual expression of Mary as Our Lady of Salt is found in Las Navalucillos, Spain.

List of mayors: Aliaga, Nueva Ecija

edit| No. | Name | Year | No. | Name | Year |

| 1 | Aniceto Maria Munoz | 1849 | 41 | Alejandro Corpus | 1911-1912 |

| 2 | Marcos Benoza | 1850 | 42 | Gregorio Pascua | 1913-1914 |

| 3 | Pedro Samson | 1851 | 43 | Pablo Medina | 1915-1920 |

| 4 | Pantaleon Dumayag | 1852 | 44 | Emiliano Soriano | 1921-1924 |

| 5 | Estanislao Yango | 1853 | 45 | Alfonso Ortega | 1925-1930 |

| 6 | Romualdo Lleva | 1854 | 46 | Raymundo Bumanlag Sr. | 1931-1934 |

| 7 | Aniceto Maria Munoz | 1855 | 47 | Joaquin Villanueva | 1935-1937 |

| 8 | Anastacio Dimaliwat | 1856 | 48 | Raymundo Bumanlag Sr. | 1938-1943 |

| 9 | Felipe Medina | 1857 | 49 | Lazaro Bayan | 1943-1947 |

| 10 | Mateo Corpus | 1858 | 50 | Antonio Romero | 1945 (1mo.) |

| 11 | Aniceto Maria Munoz | 1859 | 51 | Arcadio Moreno | 1945 (1mo.) |

| 12 | Eusebio Asuncion | 1860 | 52 | David Villamin | 1945-1946 (1.5mo.) |

| 13 | Juan Cajucom | 1861 | 53 | Pedro V. Saulo | 1948-1951 |

| 14 | Leon Flora | 1862 | 54 | Eusebio R. Bumanlag | 1952-1955 |

| 15 | Anastacio Dimaliwat | 1863 | 55 | Zacarias B. Viernes | 1956-1963 |

| 16 | Fernando Simeon | 1864-1865 | 56 | Maximo B. Serrano | 1964-1967 |

| 17 | Anastacio Dimaliwat | 1866-1867 | 57 | Quirino V. Dela Cruz | 1968-1979 |

| 18 | Agaton Mehiko | 1868-1869 | 58 | Benjamin Mamaclay | 1980 (2mo.) |

| 19 | Fernando Simeon | 1870-1871 | 59 | Nelia S. Valencia | 1980-Feb.1986 |

| 20 | Anastacio Dimaliwat | 1872-1873 | 60 | Jose T. Romero | 1986-1992 |

| 21 | Felipe Medina | 1874-1875 | 61 | Marcial R. Vargas | 1992-June 2001 |

| 22 | Alejandro Santiago | 1876-1877 | 62 | Elizabeth Vargas | 2001-June 2004 |

| 23 | Justo Agaton | 1878-1879 | 63 | Marcial R. Vargas | 2004-June 2013 |

| 24 | Eustaquio Garcia | 1880-1881 | 64 | Elizabeth Vargas | 2013-June 2016 |

| 25 | Cornelio Ortega | 1882-1883 | 65 | Gonzalo D. Moreno | 2016-June 2019 |

| 26 | Victorino Cajucom | 1884-1885 | 66 | David Angelo Vargas | 2019-June 2022 |

| 27 | Feliciano Soriano | 1886-1887 | 67 | Gilbert G. Moreno | June 30, 2022 – present |

| 28 | Escolastico delos Santos | 1888-1889 | 68 | ||

| 29 | Jose Guia | 1890-1891 | 69 | ||

| 30 | Pedro Manas | 1892-1893 | 70 | ||

| 31 | Casimiro Tinio | 1894-1895 | 71 | ||

| 32 | Apolinario Duran | 1896-1897 | 72 | ||

| 33 | Santiago Gregorio | 1898 (9mo.) | 73 | ||

| 34 | Macario delas Santos | 1898 (3mo.) | 74 | ||

| 35 | Pablo Medina | 1898 | 75 | ||

| 36 | Nicolas Cajucom | 1900-1902 | 76 | ||

| 37 | Alejandro Corpus | 1903-1904 | 77 | ||

| 38 | Feliciano Ramoso | 1905-1906 | 78 | ||

| 39 | Victor Domingo | 1907-1908 | 79 | ||

| 40 | Martin Villasan | 1909-1910 | 80 |

Diocesan Shrine of Nuestra Señora De Las Saleras

editFaith's Harvest: Aliaga's Spiritual Journey, 1849-1928

In the late 19th century, the barrio of San Juan de Dios in Aliaga became a beacon of faith. On September 23, 1868, during the feast of their patron saint, San Juan de Dios, the community received the approval for its fervent petition, allowing the celebration of Mass within their modest chapel. The chapel, a humble edifice, became a testament to the community's devotion, as the faithful gathered with pious hearts, affirming their religiosity and adherence to the Church's commandments.

The spiritual ardor of Aliaga's faithful was not confined to San Juan de Dios. By February 25, 1871, the leaders of Barrio San Vicente, inspired by their neighbors, also sought ecclesiastical independence, aspiring to erect their own parish. Their petition echoed a collective yearning for a spiritual sanctuary, a yearning that would allow them to nurture their faith more intimately.

Months later, on December 16, 1871, the collective voice of San Vicente, Santiago, and other barrios reached the Augustinian Provincial, pleading for the formation of a new parish. This move was more than administrative; it was a profound expression of a community's desire to deepen their spiritual roots and expand their place within the Church.

In the ensuing years, the spiritual tapestry of Aliaga was enriched by similar stories from Barrio Santa Maria and Barrio Toro, whose residents celebrated their patron saints’ feast days with Mass in their chapels, granted on July 14 and November 10, 1873, respectively. These celebrations were more than mere observances; they served as vibrant displays of faith and community, with each barrio cherishing its unique spiritual identity while remaining part of a greater whole.

As the years passed, the narrative of faith in Aliaga unfolded through the personal sacrifices of its clergy. The year 1928 marked a poignant chapter when Pe. Pedro Victoria, grappling with ill health amidst his parish's humid climate sought solace in a transfer. Yet, the Manila Archbishop's response, while acknowledging his plight, was a call to spiritual fortitude—a reminder that the trials he was facing were as much a part of his pastoral journey as the joys.

Through the collective and individual stories of its people, the narrative of faith in Aliaga is one

of enduring devotion, communal unity, and the intensifying quest to create a sacred space where the divine and earthly commune. It is a story that continues to be written with every Mass celebrated, every feast day observed, and every prayer uttered within the hearts of its parishioners.

Aliaga's Parish Priests and Their Journey of Faith, 1849-1928

In Aliaga, a lineage of Parish Priests has quietly sculpted the town's spiritual journey. Each priest, with his distinct touch, has contributed to the town's tale of faith.

In 1865, Fr. Joaquin Garcia took the helm at a time when the church was in disrepair. He reached out to the ecclesiastical hierarchy, seeking permission for renovations. His efforts were not merely for the church's structural integrity but as an affirmation of the community's collective faith.

Around 1862, Fr. Nicolas Zugadi took charge of the parish's finances with great care. His prudent management ensured that the church would remain a sanctuary for the community, a testament to his understanding that faith also required fiscal stewardship.

At the turn of the century, in 1898, Fr. Nicanor Gonzales OSA arrived as a new spiritual guide. His presence signified a fresh chapter for the parish, reinforcing the church's role as the heart of Aliaga's spiritual life.

A letter dated November 1, 1926 mentions Fr. Teofilo Dimaliwat writing to the Archbishop regarding a possible transfer to Manila. The Archbishop of Manila wrote back, asking whether there was adequate housing, a “convent” that could accommodate a parish priest, should a new one be assigned following his transfer. This request reflects the practical considerations of clergy assignments and the importance of ensuring continuity in pastoral care.

On the other hand, Fr. Pedro Victoria dealt with significant health issues while serving as Parish Priest. On May 18 and July 28, 1928, he communicated to the Archbishop of Manila his struggles with a liver condition and rheumatism, both, exacerbated by Aliaga's humid climate. His condition was so challenging that he requested a transfer to a less taxing environment; he even contemplated a year's vacation to recover.

In response, the Archbishop of Manila encouraged him to be resilient, to offer his sufferings for the conversion of his parishioners, and to remember that the difficult “black hours” of the rainy season would eventually give way to sunnier days. This interaction not only highlights the physical and emotional toll of pastoral duties but also the support and counsel provided by the church hierarchy during times of personal hardship for their priests.

The story finds apt continuity in Fr. Carlos Bernardo, who in 1937 informed the Archbishop of Manila

of his commitment to lead the parish in Aliaga. Fr. Bernardo's tenure as Parish Priest began on a day of promise—June 7, 1937. His arrival, reported dutifully to Archbishop O'Doherty, signaled a fresh chapter in the town's spiritual leadership. Fr. Bernardo assumed the mantle during a period that called for both spiritual guidance and the navigation of societal shifts that the late 1930s presented.

Lastly, the appointment of Rev. Fr. Felix David, though undated, signifies the unbroken legacy of pastoral leadership, a continuation of the spiritual guardianship that has been the hallmark of Aliaga's faith history.

Each of these priests, from Fr. Garcia to Fr. David, played pivotal roles in nurturing the community's spiritual welfare. They were the custodians of the town's faith, guiding their flock through services, celebrations, and personal tribulations. Their stories are interwoven with Aliaga's religious fabric, each thread representing their unwavering service and commitment to the town's spiritual growth.

Through Fire and Storm: Aliaga's Triumph Over Calamity, 1852-1887

Aliaga, Nueva Ecija, has demonstrated remarkable fortitude, enduring the ravages of time and the elements. The community's spirit has been tested by fires, typhoons, and floods, yet it stands resilient through each trial.

On November 12, 1852, a violent typhoon unleashed its fury upon the town. Fr. José Tombo, parish steward at that time, had to be resolute in the face of adversity. The very next day, he secured permission to allocate around 600 pesos from the parish funds to repair the storm's toll on the church.

A catastrophic fire in 1880 left the church and convent in ruins, reducing them to ashes. The parish responded by erecting temporary structures—a humble nipa and bamboo church and a rented wooden room for the convent. By September 2, 1884, with the spirit unbroken, the parish confidently planned to rebuild, backed by a fund of 23,000 pesos, a testament to their resolve to restore their sacred spaces.

The parish found its strength tested again on September 17, 1887, when a typhoon devastated the church. The parish acted promptly, informing the Archbishop of the damage and, subsequently, on September 29–30, faced yet another storm that called for a revision of the repair budget. Through these repeated trials, the community, supported by its clergy, maintained its dedication to repair and renew.

The narrative of Aliaga, as chronicled by these events and the actions of its parish community, is one of unwavering resilience. The town has continually risen from the ruins, driven by a collective faith and the leadership of the church, transforming each catastrophe into an opportunity for rebirth and renewed hope.

List of parish priests (1849–2024) Nuestra Señora De Las Saleras

editDiocesan Shrine of Nuestra Señora De Las Saleras, Brgy. Centro, Aliaga, Nueva Ecija: Diocese of Cabanatuan

MGA NAGING KURA PAROKO NG PAROKYA NG NUESTRA SENORA DE LAS SALERAS (1949–2024)

| PANGALAN NG PARI | TAON | |

| 1 | REV. FR. VALENTIN GARCINO PUYAT | 1849-1853 |

| 2 | REV. FR. JOSE TOMBO | 1853-1860 |

| 3 | REV. FR. NICOLAS TUGADI | 1860-1877 |

| 4 | REV. FR. JUAQUIN GARCIA | 1877-1881 |

| 5 | REV FR CARLOS VALDEZ

REV. FR. BLAS REYES REV. FR. MARIANO DELA PAZ REV. FR. BENITO CABRERA |

1881-1898 |

| 6 | REV. FR. NICANOR GONZALES | 1898-1899 |

| 7 | REV. FR. BENITO CABRERA | 1899-1901 |

| 8 | REV. FR. ADRIANO CUERPO | 1901-1903 |

| 9 | REV. FR. CRILO VERGARA | 1903-1904 |

| 10 | REV. FR. ANGEL CORTESAR | 1904-1908 |

| 11 | REV. FR. ALEJANDRO MATEO | 1908-1910 |

| 12 | REV. FR. TEOFILO MALIWAT | 1910-1912 |

| 13 | RE. FR. PEDRO VICTORIA

REV. FR. FLORENTINO FUENTES REV. FR. PEDRO IZON |

1912-1932

1942–1937 |

| 14 | REV. FR. CARLOS BERNARDO | 1937-1941 |

| 15 | REV. FR. SIMEON GENETE | 1941-1949 |

| 16 | REV.FR. DIOSDADO GUESE | 1949-1954 |

| 17 | REV. FR. JOVENCIO TANTOCO | 1954-1956 |

| 18 | REV. FR. JUAN DE JESUS | 1956-1979 |

| 19 | REV. FR. JULIO OBIAL | 1979-1983 |

| 20 | REV. FR. REGINO VIGILIA | 1983-1984 |

| 21 | REV. FR. DELFIN DIAZ | 1984-1985 |

| 22 | REV. FR. IRENEO DE GUZMAN | 1985-1986 |

| 23 | REV. FR. FRANCISCO MERCURIO | 1986-1988 |

| 24 | REV. FR. DANTE F. GARCIA | 1988-1995 |

| 25 | REV. FR. ARIEL MUSNGI

MOST. REV. ELMER I. MANGALINAO |

1995-2001 |

| 26 | REV. FR. ANGELITO PARULAN | 2001-2007 |

| 27 | REV. FR. ARMANDO CALEON | 2007-2008 |

| 28 | REV. FR. DANILO CIPRIANO | 2009-2014 |

| 29 | REV. FR. ROBERT I. DELA CRUZ | 2014-2021 |

| 30 | REV. FR. FRANZ JOSEPH G. AQUINO | 2021-PRESENT |

List of parish priests (1978–2024) St. John the Baptist

editDiocesan Shrine of St. John the Baptist, Brgy. Bibiclat, Aliaga, Nueva Ecija: Diocese of Cabanatuan

| Name | Year |

| Rev. Fr. Remigio G. Malgapo | July 1978 – 1984 |

| Rev. Fr. Jose Y. Fajardo | 1984-1985 |

| Rev. Fr. Ireneo De Guzman | 1985-1986 |

| Rev. Fr. Antonio Mangahas | 1986-1989 |

| Rev. Fr. Victor N. Cruz | 1989-1993 |

| Rev. Fr. Cesar M. Bactol | 1993-1995 |

| Rev. Fr. Enrico L. Garcia | 1995-2001 |

| Rev. Fr. William S. Villaviza | 2001-2008 |

| Rev. Fr. Carlos A. Padilla | 2008-2014 |

| Rev. Fr. Elmer S. Villamayor | 2014-2021 |

| Rev. Fr. Perfecto B. Alto Jr. | 2021-2024 (present) |

General Manuel Tinio and the Battle of Aliaga

editGeneral Manuel Tinio, a revolutionary leader who fought against the Spanish colonizers. General Tinio was born in Aliaga, Nueva Ecija, on June 17, 1877. He joined the Katipunan, a secret society that was fighting for Philippine independence, in 1896. He was a brilliant military strategist, and he played a key role in many of the battles against the Spanish. After the Spanish were defeated, General Tinio continued to fight for Philippine independence against the Americans. He died of liver disease on February 22, 1924, in Cabanatuan City.

Manuel Tinio y Bundoc (June 17, 1877 – February 22, 1924) was the youngest General of the Philippine Revolutionary Army, and was elected Governor of the province of Nueva Ecija, Republic of the Philippines in 1907. He is considered to be one of the three "Fathers of the Cry of Nueva Ecija", along with Pantaleon Valmonte and Mariano Llanera.

Aliaga-Nueva Ecija: the Birth Place of Gen. Tinio

The Tinio family, whose most illustrious son is Manuel Tinio, is conceivably the most prominent and wealthiest family in the province of Nueva Ecija. Too, the family was the largest landowner in Central Luzon, if not the entire Philippines, prior to the declaration of Martial Law.

The Tinios, like the Rizals, are of Chinese descent. An archival document from San Fernando, Pampanga dated 1745 describes a certain Domingo Tinio as a Chino Cristiano or baptized Chinese.

Juan Tinio, the first ancestor on record had twin sons who were baptized in Gapan in 1750. In the baptismal record he is described as an indio natural, a native Filipino. From this it can be deduced that either his grandfather or an earlier ancestor was a pure-blooded Chinese. (Juan Tinio became the first middleman of the Tobacco Monopoly when it was established in 1782 and held the position for two years.)

Juan Tinio's great-grandson, Mariano Tinio Santiago, was the father of Manuel Tinio. Mariano and his siblings, originally named Santiago, changed their family name to Tinio, their mother's family name, in accordance with Gov.-Gen. Narciso Claveria's second decree of 1849 requiring all Indios and Chinese mestizos to change their family names if these were saints’ names.

Although he was a native of San Isidro, Nueva Ecija, Mariano eventually settled in Licab, then a barrio of Aliaga beside Lake Canarem, and carved out rice fields from the heavily forested area. Having served as Cabeza de Barangay of the place, he came to be known as ‘Cabezang Marianong Pulang Buhok’ (Cabezang Mariano the Red-Haired). Although he eventually became a big landowner, he lived very simply on his lands. Mariano was a man of strong principles, and even led a petition to the Governor-General denouncing the corruption and abuses of the Alcalde Mayor, the governor of Nueva Ecija, and asking for his recall. Cabesang Mariano married several times and, in the fashion of the time, engaged in extramarital affairs, siring numerous progeny. His fourth and last wife was Silveria Misadsad Bundoc of Entablado, Cabiao. He died on October 11, 1889, in Licab. Silveria, a woman of very strong character, lived on until the second decade of the 20th century.

Manuel Tinio was born to Silveria on June 17, 1877, in Licab, a barrio of Aliaga that became an independent municipality in 1890. He was the only son and had two sisters, the eldest, Maximiana, married Valentin de Castro of Licab and Catalina, the youngest, married Clemente Gatchalian Hernandez of Malolos, Bulacan. Manuel was his mother's favorite, his father having died when Manuel was twelve.

Battle of Aliaga 1897

editThe passionate rebels reorganized their forces the moment Spanish pursuit died down. Tinio and his men marched with Gen. Llanera in his sorties against the Spaniards. Llanera eventually made Tinio a captain.

The aggressive exploits of the teen-aged Manuel Tinio reached the ears of General Emilio Aguinaldo, whose forces were being driven out of Cavite and Laguna, Philippines. He evacuated to Mount Puray in Montalban, Rizal and called for an assembly of patriots in June 1897. In that assembly, Aguinaldo appointed Mamerto Natividad Jr. as commanding general of the revolutionary army and Mariano Llanera as vice-commander with the rank of Lt.-General. Manuel Tinio was commissioned a Colonel and served under Gen. Natividad.

The constant pressure from the army of Gov. Gen. Primo de Rivera drove Aguinaldo to Central Luzon. In August, Gen. Aguinaldo decided to move his force of 500 men to the caves of Biac-na-Bato in San Miguel, Bulacan because the area was easier to defend. There, his forces joined up with those of Gen. Llanera. With the help of Pedro Paterno, a prominent Philippines lawyer, Aguinaldo began negotiating a truce with the Spanish government in exchange for reforms, an indemnity, and safe conduct.

On August 27, 1897, Gen. Mamerto Natividad and Col. Manuel Tinio conducted raids in Carmen, Zaragoza and Peñaranda, Nueva Ecija. Three days later, on the 30th, they stormed and captured Santor (now Bongabon) with the help of the townspeople. They stayed in that town till September 3.

On September 4, with the principal objective of acquiring provisions lacking in Biac-na-Bato, Gen. Natividad and Col. Manuel Tinio united their forces with those of Col. Casimiro Tinio, Gen. Pío del Pilar, Col. Jose Paua and Eduardo Llanera for a dawn attack on Aliaga. (Casimiro Tinio, popularly known as ‘Capitan Berong’, was an elder brother of Manuel through his father's first marriage.)

Thus began the Battle of Aliaga (September 4–5, 1897, between the Philippine revolutionaries of Nueva Ecija and the Spanish forces of Governor General Primo de Rivera), considered one of the most glorious battles of the rebellion. The rebel forces took the church and convent, the Casa Tribunal and other government buildings. The commander of the Spanish detachment died in the first moments of fighting, while those who survived were locked up in the thick-walled jail. The rebels then proceeded to entrench themselves and fortify several houses. The following day, Sunday the 5th, the church and convent as well as a group of houses were put to the torch due to exigencies of defense.

Spanish Governor General Primo de Rivera fielded 8,000 Spanish troops under the commands of Gen. Ricardo Monet and Gen. Nuñez in an effort to recapture the town of Aliaga. A column of reinforcements under the latter's command arrived in the afternoon of September 6. They were met with such a tremendous hail of bullets that the general, two captains and many soldiers were wounded, forcing the Spaniards to retreat a kilometer away from the town to await the arrival of Gen. Monet and his men. Even with the reinforcements, the Spaniards were overly cautious in attacking the insurgents. When they did so the next day, they found the town already abandoned by the rebels who had gone back to Biac-na-Bato. Filipino casualties numbered 8 dead and 10 wounded.

Gen. Natividad and Col. Manuel Tinio shifted to guerrilla warfare. The following October with full force they attacked San Rafael, Bulacan to get much-needed provisions for Biac-na-Bato. The battle lasted several days and, after getting what they came for, they left a detachment in Bo. Kaingin to hold back the Spanish reinforcements from Baliwag, Bulacan. To divert Spanish forces from Nueva Ecija, Natividad and Tinio attacked Tayug, Pangasinan on Oct. 4, 1897, occupying the church in the heart of the poblacion.

Meanwhile, peace negotiations continued and in October Aguinaldo gathered together his generals to convene a constitutional assembly. On Nov. 1, 1897 the Constitution was unanimously approved and on that day the Biac-na-Bato Republic was established.

However, Gen. Natividad, who believed in the revolution, opposed the peace negotiations and continued to fight indefatigably from Biac-na-Bato. On Nov. 9, while leading a force of 200 men with Gen. Pío del Pilar and Col. Ignacio Paua, Natividad was killed in action in Entablado, Cabiao. Col. Manuel Tinio brought the corpse back to the general's grieving wife in Biac-na-Bato. (Incidentally, Gen. Natividad's widow, Trinidad, was the daughter of Casimiro Tinio–"Capitan Berong".) With the death of the army's commanding general, Col. Manuel Tinio was commissioned Brigadier General and designated as commanding general of operations on Nov. 20, 1897. Gen. Tinio, all of 20 years, became the youngest general of the Philippine Revolutionary Army. (Gregorio del Pilar, already 22, was only a Lt. Colonel at that time.)

On Dec. 20, 1897, the Pact of the Biac-na-Bato was ratified by the Assembly of Representatives. In accordance with the terms of the peace pact, Aguinaldo went to Sual, Pangasinan, where he and 26 members of the revolutionary government boarded a steamer to go into voluntary exile in Hongkong. The Novo-Ecijanos in the group were Manuel Tinio, Mariano and Eduardo Llanera, Benito and Joaquin Natividad, all signatories of the Constitution.

In Hongkong, the exiles agreed among themselves to live as a community and spend only the interest of the initial P400,000 the Spanish Government had paid in accordance with the Pact of the Biac-na-Bato. The principal was to be used for the purchase of arms for the continuation of the revolution at a future time. The Artacho faction, however, wanted to divide the funds of the Revolution among themselves. The Novo-Ecijanos did not vote with the opportunist Artacho ‘faction’, and, being relatively well off, thanks to a relative who provided them with funds (Trinidad Tinio vda. de Natividad), "they got a house where they lived like a republic", as they said.

Geography

editIt has a comparatively cool and healthful climate, and is situated about midway between the Pampanga Grande and the Pampanga Chico rivers, in a large and fertile valley. Historically, the principal products were mostly agricultural such as rice, tomato, eggplant, squash.[5]

Barangays

editAliaga is politically subdivided into 26 barangays. Each barangay consists of puroks and some have sitios.

- Betes

- Bibiclat

- Bucot

- La Purisima

- Magsaysay

- Macabucod

- Pantoc

- Poblacion Centro

- Poblacion East I

- Poblacion East II

- Poblacion West III

- Poblacion West IV

- San Carlos

- San Emiliano

- San Eustacio

- San Felipe Bata

- San Felipe Matanda

- San Juan

- San Pablo Bata

- San Pablo Matanda

- Santa Monica

- Santiago

- Santo Rosario

- Santo Tomas

- Sunson

- Umangan

| Barangay | Short Story |

| Bestes | Covered with wild grass and trees, Brgy. “Betes” meaning large trees that can hardly be cut down. It began as Sitio (site or place that form parts of Barangay), later became a Barangay. Since Barangay Betes used to be covered with large trees and grass, after the clean-up, people decided to plant crops for food.

Number of Population: 2,472 Number of Household: 606 Number of Purok: 6 Number of Schools: 1 Land Area: 5,120,876 |

| Bibiclat | Official and original name of Brgy. Bibiclat was “San Juan Bautista” created and organized in 1899 in honor of the Patron Saint. The community established in 1836, made it 13 years earlier than the town foundation of Aliaga, Nueva Ecija. Bibiclat is a plural form of the word “Bicat” meaning Python in Ilocano dialect. Ilocanos from Lapog, Ilocos Sur were the first settlers, followed by the Pampango from Pampanga. Tagalog is the dialect used by the town people whose faith is Roman Catholic. St.John the Baptist Church situated in Brgy. Bibiclat is known for its Taong Putik Festival, celebrated every June 24.

-1904 arrival of the Americans: there were private schools in English, Ilocano, and Tagalog. -1944 more than 20 young men from the barrio fought at the WWII. One evidence of the barrio's heroism occurred in November, 1944 when 13 Japanese soldiers led by Capt. Sato were killed by civilians and the USAFE Guerillas under of the able command of the late Carlos Nucom of Talavera. -1966 Barangay High School was opened led by Lay Leaders, produced the first batch of graduates in 1969. It is the first Barangay High School in the division of Nueva Ecija to graduate students. -1970 (August 25) the Barrio Elementary School became Central School as a result of the division of Aliaga district, the East and the West. Bibiclat is the biggest barangay in Aliaga with rice fields and vegetable fields, and its musical bands.

Number of Population: 8,355 Number of Household: 2,048 Number of Purok: 7 Number of Schools: 3 Land Area: 9,470,745 |

| Bucot | Arrival of the Spaniards, Brgy. Bucot meaning crooked or twisted; was a flat plain which later converted to a farm land. Original name was Brgy. San Isidro named after its Patron Saint. However, there was a crooked or twisted river once ran across the barrio. One day a stranger passed by and asked the resident who was about 80 years old; what was the name of the river? He replied that the river name is “Sapang Bucot”, since then, it was called Brgy. Bucot.

Number of Population: 5,355 Number of Household: 1,313 Number of Purok: Number of Schools: 1 Land Area: 2,548,785 |

| La Purisima | It is one of the oldest Brgy. in the Municipality. During American occupation it was called “tabing ilog” situated in the North Bank of the Talavera River sliced through the boundary of Quezon and Aliaga.

-1837 big logs carried by flood from Caraballo mountains clogged the Talavera River, causing the portion of the river that ran between Brgy. Pantoc and Brgy. La Purisima to flood the town of Aliaga during rainy season. The closure of the Talavera River led to arrival of immigrants from Ilocos Region. -1913 Barrio Tabing Ilog became a barangay during the time of Mayor Gregorio Pascua. -1914 after the WWII broke, the residents of tabing ilog moved to Brgy. Poblacion and settled at the “River Side”. -1922 (June 12) opening of Elementary School in English. The first teacher was Mr. Arsenio Dawang (from barangay Sto. Tomas) but closed after school year 1922–1923. However, the Elementary School re-opened after the WWII. -1936 Brgy. Tabing Ilog was now called Brgy. La Purisima in honor of its Patroness, La Purisima Concepcion. Number of Population: 2,300 Number of Household: 511 Number of Purok: 4 Number of Schools: 1 Land Area: 3,330,984 |

| Macabucod | This brgy. was a forest land that used to be part of Brgy. Sto. Tomas; there were no settlers nor inhabitants. After several years, sudden inhabitants from groups of people called this place “Bagong Silang”. Trees and grass were cleared, made way for more housing from new settlers including an Elementary School. The name “Macabucod” came from the word ‘bukod’ (separated) because of its separation from Brgy. Sto. Tomas.

Number of Population: 2,901 Number of Household: 645 Number of Purok: 7 Number of Schools: 1 Land Area: 527,940 |

| Magsaysay | Bgry. Magsaysay originally was a sitio or part of Brgy. Santiago. The leaders of this sitio were Agripino Alfaro and Gregorio Moreno. It was recognized as a Brgy. on February 14, 1957, called “Al Magsaysay” as a mixture of two names; Nueva Ecija Governor Amado Q. Aleta and President Ramon Magsaysay. After the death of President Magsaysay on March 17, 1957; the Brgy. changed its name from Al Magsaysay to “Brgy. Magsaysay”. San Isidro is their Patron Saint.

Number of Population: 1190 Number of Household: 265 Number of Purok: Number of Schools: 1 Land Area:4,720,190 |

| Pantoc | -1920 there were only 30 households with population of 50. The first Barrio Lieutenant was Mr. Gavino Tumpalan.

-1939 opening of Elementary School by its land donor Mr. Gaudencio Molina, the Barrio was named “San Gaudencio Molina” - in later years the barrio is known as Brgy. Pantoc, believed to be the description of the barrio's hilly land “bundok bundok” (Santos, Lourdes V. 2023) later known as “Brgy. Pantoc” - Governor Dr. Leopoldo Diaz commissioned a Pantoc Dam Project to prevent Aliaga from flood. - September 20, 1979 the school had its electric light through the joint efforts of Mr. Nacario Gonzales, in-charge of the school and barrio council, during the time of Mayor Quirino Dela Cruz. - Predominantly Catholics and Iglesia ni Kristo, its inhabitants are engaged in farming.

Number of Population: 2,786 Number of Household: 620 Number of Purok: 7 Number of Schools: 1 Land Area: 2,599,572 |

| Poblacion Centro

Poblacion East 1 Poblacion East 2 Poblacion West 3 Poblacion West 4 |

1914 after the WWII, the residents of Brgy. La Purisima moved to Brgy. Poblacion and settled at the “River Side”.

Other residents from Brgy. San Emiliano which was a district town proper or Poblacion, called “Cabasta”; separated from Brgy. San Emiliano and form the new town proper. In Early 1980's Población East I, East II, West III and West IV was originally part of the Town Proper of Aliaga, the East part known as Hulo or Tulay na bato which the National high School is located and in the west part known as Luwasan, During the Term of Mayor Nelia Valencia he made a significant astride to create a barangay along the quadrant vicinity of the town proper, she stablish to make a barangay in East Part as Población East I and Población East II and two in west Part as Población west 3 and Población west 4. As of year 2023: 1) Poblacion Centro is where the Municipal Town Hall, Government Offices, Police Station, Nuestra Senora De Las Saleras Church, Elementary Schools, Fire Station, and other major establishments 2) Poblacion East 1 became residential areas and farmland 3) Poblacion East 2 consist of farmland, the Aliaga National High School, gasoline stations, and more residential area 4) Poblacion West 3 is where the Public Market and commercial areas are 5) Poblacion West 4 holds residential area and schools Barangay Centro: Number of Population: 2536 Number of Household: 564 Number of Purok: Number of Schools: 2 Land Area: 212,698 Barangay East 1 & East 2: Number of Population: 2627 / 1667 Number of Household: 584 / 371 Number of Purok: Number of Schools: 2 / 1 Land Area: 1,219,285 / 719,29 Barangay West 3 & West 4: Number of Population: 1331/ 768 Number of Household: 296/170 Number of Purok: Number of Schools: 0 / 1 Land Area: 70738 / 170,738 |

| San Carlos | During Spanish occupation, Brgy. San Carlos was a forest land with wild animals with no inhabitants. The first settlers were native of Ilocos region who built their houses by the edge of the forest and later increased their rice farm land and vegetable farms. More settlers increased and form a community of their own. Their Patron Saint from the native town of the settlers in Ilocos was San Carlos Barromeo, therefore, the Bgry. is called “Bgry. San Carlos” celebrating their feast day every November 4. Brgy. San Carlos has a boundary at Brgy. Dolores, Sto. Domingo Town.

Number of Population: 3,608 Number of Household: 801 Number of Purok: 7 Number of Schools: 2 Land Area:3,350,833 |

| San Emiliano | Originally a district town proper or Poblacion, called “Cabasta” because of its location along the creek. During the Japanese occupations, the inhabitants of the district evacuated to the placed now occupied by the Municipal cemetery in order to escape the harassment inflicted by the Japanese soldiers. During the Liberation, they returned to the respective homes.

-1954 Cabasta became a Barrio during the time of Lieutenant Proceso Tolentino, with the support from Mayor Zacarias B. Viernes. -the barrio Cabasta is part of the land owned by Don Emiliano Soriano (land owner and former town Mayor), the name was changed to “Brgy. San Emiliano”

Number of Population: 1,676 Number of Household: 373 Number of Purok: 7 Number of Schools: 1 Land Area: 3,368,934 |

| San Eustacio | Known by the name “Pulong Mayaman”, this piece of land owned by the Kapitan also former town Mayor Anastacio Dimaliwat. After his death, his daughter inherited the land. However, with the Presidential Decree No.27 the Farmers Emancipation Act, this piece of land was distributed to the tenants. In recognition of the Kapitan's kindness and generosity, the tenants changed the name to “Brgy. San Eustacio”.

Number of Population: 2,597 Number of Household: 578 Number of Purok: Number of Schools: 1 Land Area: 1,950,237 |

| San Felipe Bata | Brgy. San Felipe Bata was created by Congressional Act of the defunct Congress of the Philippines in 1970. A part of the old San Felipe, it held the national road that links to Cabanatuan City and Tarlac City.

A progressive barangay has a few landmarks such as health center donated by Provincial Board under Governor Eduardo Joson, a complete elementary school, and a catholic chapel.

Number of Population: 2,133 Number of Household: 474 Number of Purok: Number of Schools: 1 Land Area: 1,758,380 |

| San Felipe Matanda | In Spanish time, this Brgy. was a dense forest. Kapitan (Teniente del Barrio) and former Mayor Felipe Medina (1874–1875) was their recognized leader. He had the forest cleaned to form a barrio, therefore, the Brgy. was named after him “Brgy. San Felipe” with San Felipe Neri as their Patron Saint. With the separation of San Felipe Bata (East side) and San Felipe Matanda (West side).

San Felipe Matanda was the only hacienda during the American occupation owned by Dona Sisang De Leon and after on the barrio of small hunts, dirt trails, deep wells and gas lamps, it has transformed into a highly progressive community with agricultural and residential area.

Number of Population: 3,056 Number of Household: 679 Number of Purok: 7 Number of Schools: 1 Land Area: 1,869,840 |

| San Juan | Pre-Spanish era, Brgy. San Juan was called “Pintong Gubat” due to its forest land with wild animals. Later the barrio renamed to Brgy. San Juan in honor of former Mayor Juan Cajucom and its Patron Saint San Juan de Dios.

-1861 Pintong Gubat became a Barrio -1965 the barrio established Elementary School -1966 road construction during the time of President Diosdado Macapagal under roads-building programs brought about the electric power and electric appliances The earliest settlers were mostly Ilocanos who were responsible in clearing the land. Upon order of the Governadorcillo. Roads were built leading to the nearly sitios and barrios for the transportation of their crops. That marked the beginning of San Juan progress. During the dark days of the last global war, San Juan has a Huk don. As was to be expected. The hard fact was the Huks were there only to safeguard the security of the barrio. Under the leadership of Barangay Captain Momerto Legaspi, his councilmen, and with the cooperation of the barangay residents, San Juan with its 500 hectares of the land and 3,000 people will match ahead to prosperity. Add to this the presence of irrigation system and an imposing chapel which houses its patron Saint San Juan de Dios.

Number of Population: 5,794 Number of Household:1,287 Number of Purok: 7 Number of Schools: 2 Land Area: 4,060,850 |

| San Pablo Bata | The newly constructed road in Brgy. San Pablo (later called San Pablo Matanda) leading to Tarlac via Zaragoza, gave birth to a new Barrio in 1921 called “Brgy. San Pablo Bata” separated from Brgy. San Pablo Matanda. The Brgy. later established a school in 1951 and chapel, due to more population in its barangay.

The first school building in San Pablo Bata was erected on a lot owned by Pedro Albino; The first chapel, on the lot of Miguel Albino. When Candido Albino was the barrio Lieutenant, a new school house was built on the lot bought from Feder Santos. Opened in 1951, the first teacher was Mrs. Eufemia Sanqueza.

Number of Population: 2,2267 Number of Household: 504 Number of Purok: 5 Number of Schools: 1 Land Area: 3,744,346 |

| San Pablo Matanda | Brgy. San Pablo Matanda was named after Pablo Tagatac Albino; one of the four settlers from Sarrat, Illocos Norte who arrived in San Pablo in 1854. The other three settlers were Diego Enriquez, Julian Castillo, and Teodora Banot. San Pablo was one of the first barrio that has national road from Cabanatuan City to Tarlac City.

This gave birth to a new barrio in 1921 called San Pablo Bata. The original barrio was renamed San Pablo Matanda. Number of Population: 1,357 Number of Household: 301 Number of Purok: 4 Number of Schools: 1 Land Area: 3,444,450 |

| Sta. Monica | Brgy. Sta. Monica fondly called “Munique” located in the western tip of Aliaga, was a woodland during the early years of the Spanish regime. It was dense forest teaming with wild animals, such as deer, wild pigs, and ducks. Before Brgy. Sta. Monica was part of Sto. Rosario. At present it housed the Talavera River (Sta. Monica – Lapaz, Tarlac River). There is a hanging bridge connecting Aliaga to Licab Town and Zaragoza Town. On the opposite side of the hanging bridge, the locals called the place “Pugad Lawin”. Situated in Brgy. Sta. Monica is “Gapumaca Communal Irrigation System” a part of canal system in Zaragoza, Nueva Ecija. The project is ongoing in year 2023 and known as Gapumaca Dam.

Number of Population: 2675 Number of Household: 594 Number of Purok: 6 Number of Schools: 1 Land Area: 3,960,704 |

| Santiago | Brgy. Santiago is one of the oldest barrios in Aliaga, named after a Spanish General Santiago de Galicia and St. James its Patron Saint. The feast day is celebrated on July 25 to thank the Patron Saint for the wellness that was given to the barrio's inhabitants and for the good harvest of rice and plantations. It is believed that there was account of miracles during the smallpox epidemic, that town people were saved from the smallpox. As well as farmers’ Novena prayers dedicated to St. James, praying for rain water to be able to plant rice and vegetables; and the rain would come. The feast day is on July 25.

Number of Population: 1,306 Number of Household: 291 Number of Purok: 6 Number of Schools: 1 Land Area: 4,468,320 |

| Sto. Rosario | “Malitlit” was the original name of Brgy. Sto.Rosario because of its forest composed of small trees. Due to dedication to Mother Mary, farmers often prayed the holy rosary before leaving their home, later Brgy. Malitlit was renamed to Brgy. Sto.Rosario.

Sto. Rosario consists of Sitio Katuray and Sitio Poitan. It has a complete elementary school; irrigated rice lands the roads and bridges that connect it to the adjacent barangay to the town proper.

Number of Population: 2,916 Number of Household: 648 Number of Purok: Number of Schools: 1 Land Area: 4,350,295 |

| Sto. Tomas | Brgy. Sto. Tomas was called Barrio “Pulong Gubat” due to its forest land. Settlers from Ilocos region arrived in 1875 however, it took them around 30 years to clear the land to be suitable for inhabitants. Its Patron Saint Thomas (Sto. Tomas) was chosen from the settlers’ town origin in Ilocos Norte.

The first Barrio Lieutenant was from the Pascua clan. Then from the Lomboy, and Bumanlag clans.

Number of Population: 6,293 Number of Household: 1,399 Number of Purok: Number of Schools: 2 Land Area: 5,686,629 |

| Sunson | Located at the Northeast of Brgy. Bibiclat and almost adjoining Brgy. San Carlos, lies a small strip of land known to many as Sunson. First settlers arrived in 1892 converted the forest land into agricultural land. Their product “Gabing Sunsong” is a variety of yam known by villagers nearby. Later the village was called “Sunson” for short and eventually, Sunson Village became Brgy. Sunson.

Number of Population: 978 Number of Household: 217 Number of Purok: Number of Schools: 1 Land Area: 2,164,310 |

| Umangan | In the early years of the Spanish regime, Brgy. Umangan was a dense forest with wild animals such as deer, wild pigs, and ducks which was known for its hunting ground (in Tagalog umangan). Once the forest was cleared, the land turned into agricultural land. They built huts made of bamboos and cogon grass. With increase of population in the Brgy., the place is later called Brgy. Umangan.

A story is told about a hunter who chanced to pass by and did not know that it was the same place he used to hunt wild animals a few years back because of the presence of many houses. He told the inhabitants that their village was once a hunting ground or “Umangan” of wild animals. From that time on, it was called Umangan.

Number of Population: 4,308 Number of Household: 958 Number of Purok: Number of Schools: 2 Land Area: 4,215,320 |

Climate

edit| Climate data for Aliaga, Nueva Ecija | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 29 (84) |

30 (86) |

32 (90) |

34 (93) |

33 (91) |

31 (88) |

30 (86) |

29 (84) |

30 (86) |

30 (86) |

30 (86) |

29 (84) |

31 (87) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 19 (66) |

20 (68) |

20 (68) |

22 (72) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

22 (72) |

21 (70) |

20 (68) |

22 (72) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 4 (0.2) |

6 (0.2) |

7 (0.3) |

12 (0.5) |

61 (2.4) |

89 (3.5) |

96 (3.8) |

99 (3.9) |

81 (3.2) |

88 (3.5) |

37 (1.5) |

13 (0.5) |

593 (23.5) |

| Average rainy days | 2.5 | 3.0 | 4.1 | 6.3 | 15.8 | 19.4 | 22.5 | 21.6 | 20.1 | 17.5 | 9.6 | 4.0 | 146.4 |

| Source: Meteoblue[6] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: Philippine Statistics Authority[7][8][9][10] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tagalog and Ilocano are the most important and the major languages of the municipality, minority speaks Kapampangan.

Economy

editPoverty incidence of Aliaga

10

20

30

40

2006

30.50 2009

25.43 2012

18.99 2015

16.41 2018

6.71 2021

13.79 Source: Philippine Statistics Authority[11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18] |

Culture

editThe Taong Putik Festival is an annual festival held in the municipality on the feast day of Saint John the Baptist every 24th day of June. The religious festival is celebrated by the locals and devotees to pay homage to Saint John the Baptist by wearing costumes patterned from his attire. Devotees soak themselves in mud and cover their body with dried banana leaves and visit houses or ask people for alms in the form of candles or money to buy candles which is them offered to Saint John the Baptist.

Sister cities

edit- Cabanatuan, Nueva Ecija

References

edit- ^ Municipality of Aliaga | (DILG)

- ^ "2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. Quezon City, Philippines. August 2016. ISSN 0117-1453. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 25, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ a b Census of Population (2020). "Region III (Central Luzon)". Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay. Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ "PSA Releases the 2021 City and Municipal Level Poverty Estimates". Philippine Statistics Authority. 2 April 2024. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Aliaga". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 661.<references></references>

Cradle and Fields of Faith: The Story of Aliaga, Nueva Ecija (2024): Moreno, Aquino, Dela Cruz, Reyes, Apostol, Doble, Lochan, et al.

<references></references>Municipality of Aliaga 2022-2024

- ^ "Aliaga: Average Temperatures and Rainfall". Meteoblue. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ Census of Population (2015). "Region III (Central Luzon)". Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay. Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ^ Census of Population and Housing (2010). "Region III (Central Luzon)" (PDF). Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay. National Statistics Office. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ Censuses of Population (1903–2007). "Region III (Central Luzon)". Table 1. Population Enumerated in Various Censuses by Province/Highly Urbanized City: 1903 to 2007. National Statistics Office.

- ^ "Province of Nueva Ecija". Municipality Population Data. Local Water Utilities Administration Research Division. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ "Poverty incidence (PI):". Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ "Estimation of Local Poverty in the Philippines" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. 29 November 2005.

- ^ "2003 City and Municipal Level Poverty Estimates" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. 23 March 2009.

- ^ "City and Municipal Level Poverty Estimates; 2006 and 2009" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. 3 August 2012.

- ^ "2012 Municipal and City Level Poverty Estimates" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. 31 May 2016.

- ^ "Municipal and City Level Small Area Poverty Estimates; 2009, 2012 and 2015". Philippine Statistics Authority. 10 July 2019.

- ^ "PSA Releases the 2018 Municipal and City Level Poverty Estimates". Philippine Statistics Authority. 15 December 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ "PSA Releases the 2021 City and Municipal Level Poverty Estimates". Philippine Statistics Authority. 2 April 2024. Retrieved 28 April 2024.