The African forest buffalo (Syncerus caffer nanus), also known as the dwarf buffalo or the Congo buffalo, is the smallest subspecies of the African buffalo.[1] It is related to the Cape buffalo (Syncerus caffer caffer), the Sudan buffalo (Syncerus caffer brachyceros), and the Nile buffalo (Syncerus caffer aequinoctialis). However, it is the only subspecies that occurs mainly in the rainforests of Central Africa and Western Africa, with an annual rainfall around 1,500 mm (59 in).[2] It has been proposed to represent a distinct species, Syncerus nanus.[3]

| African forest buffalo | |

|---|---|

| |

| At the San Diego Zoo | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Subfamily: | Bovinae |

| Genus: | Syncerus |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | S. c. nanus

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Syncerus caffer nanus (Boddaert, 1785)

| |

| |

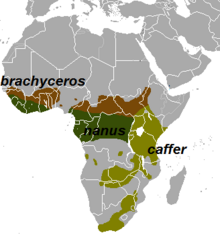

| The range in dark green | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Syncerus nanus | |

Description

editThe African forest buffalo is a small subspecies of the African buffalo. Cape buffaloes weigh 425 to 870 kg (937 to 1,918 lb),[4] whereas African forest buffaloes are much lighter, weighing in at 250 to 320 kg (550–705 lbs).[1] Weight is not the only differentiation, however; this subspecies has a reddish-brown hide that is darker in the facial area. The shape and size of the horns distinguish African forest buffalo from the other subspecies. African forest buffalo have much smaller horns than their savanna counterparts the Cape, Sudan and Nile buffalo.[1][5] Cape buffalo horns often grow and fuse together, but African forest buffalo horns rarely fuse.

Ecology

editAfrican forest buffalo live in the rainforests of West and Central Africa;[2] however, their home ranges typically consist of a combination of marshes, grassy savannas and the wet African rainforests. Savannas are the area where the buffalo graze, while the marshes serve as wallows and help the animals handle insects.[6] African forest buffalo are very rarely observed in the unbroken canopy of the forests.[7][8] They instead spend most of their time in clearings, grazing on grasses and sedges.[9] Consequently, their diet is primarily made up of grasses and other plants that grow in clearings and savannas.[10]

The mixture of habitats is essential for the African forest buffalo. Expansion and encroachment of the rainforest on the surrounding savannas and openings are major difficulties of maintaining the ecosystem. African forest buffalo enjoy old logging roads and tracks, where the forest is thinner and grass and other foods can grow. In these areas, African forest buffalo depend on the grass that is able to develop as a result of the areas that have been previously clear-cut.[11] In some areas park management staff burn off the savannas on a regular basis to keep the rainforest from growing onto the savannas and changing the ecosystem of the area.[12]

Large home ranges can be associated with less-productive habitats;[13] however, a larger area of open grassland has been observed to have a positive relationship with herd size.[14] Home ranges remain remarkably constant and stable year after year. The only documentation of the actual home range boundaries of these animals is relatively recent, so only time will tell how these boundaries remain over large lengths of time; however, studies have shown almost no movement in range boundaries from one year to the next.[1][5]

Although the area included in a home range is relatively constant over time, the preferences in regard to what part of the range is most used shift with the seasons. From March until August, African forest buffalo spend most of their time in the forest, while from September through February, they favor the savannas and marshes.[5][15]

African forest buffalo arrange themselves into herds, which help in defense against predators; however, they are not immune to assault. Among predators, the African leopard is the most common, but is generally only a threat to young buffaloes and will feast on them only when they have the opportunity. The Nile crocodile is the only predator which is capable of killing an adult buffalo.[12]

Social behaviour

editAfrican forest buffalo have relatively small herds compared to the well-studied Cape buffalo. Cape buffalo can have herds of over 1,000 members; however, African forest buffalo stay in much smaller groups—as small as three and rarely over 30. If African forest buffalo are in a large group, they spend more time grazing, since there is less need to devote time to alert behavior.[16]

A herd of African forest buffalo typically consists of one or occasionally two bulls and a harem of adult females, juveniles and young calves. Unlike Cape buffalo bulls, African forest buffalo bulls remain with the herd continually, year round. On the other hand, Cape buffalo bulls stay in bachelor herds until the wet season, when young bulls join the females, mate, help protect the young calves and then leave. Animals usually remain in the same herd for their entire lives. Herd-switching in cows has been observed; however, this is not a common occurrence.[17] Herds can split into two groups for a short period of time before merging back together.[18]

African forest buffalo are relatively unaffected by seasonal cycles. However, in the wet season, herds are more spread out in the forest[18][19] and these animals tend to use resting places based on sand during the wet season, but use dirt and leaves during the dry season.[8] Moreover, in open habitats such as clearings, herds are more aggregated when resting and are more rounded in shape than herds in forest habitats during the wet season.[20]

Notes

edit- ^ a b c d Korte 115

- ^ a b Melletti et al. 1312

- ^ Groves, C.; Grubb, P. (2011). Ungulate Taxonomy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ^ Cape Buffalo, Encyclopedia Britannica https://www.britannica.com/animal/Cape-buffalo

- ^ a b c Melletti M. and Burton J. (eds). 2014.

- ^ Korte 123

- ^ Blake 81

- ^ a b Melletti, Penteriani, and Boitani 186

- ^ Melletti et al. 1313

- ^ van der Hoek et al. 1

- ^ Bekheis, Jong, and Prins 674

- ^ a b Korte 116

- ^ Korte 122

- ^ Korte 234

- ^ Korte 121

- ^ Melletti et al. 1315

- ^ Korte 125

- ^ a b Melletti et al. 1316

- ^ Melletti et al. 1317

- ^ Melletti et al. 1318>Melletti M. and Burton J. (Eds). 2014. Ecology, Evolution and Behaviour of Wild Cattle. Implications for Conservation (Cambridge University Press).

References

edit- Bekhuis, Patricia D.B.M.; De Jong, Christine B.; Prins, Herbert H. T. (2008). "Diet selection and density estimates of forest buffalo in Campo-Ma'an National Park, Cameroon". African Journal of Ecology. 46 (#4): 668–675. Bibcode:2008AfJEc..46..668B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.2008.00956.x.

- Blake, Stephen (2002). "Forest Buffalo Prefer Clearings to Closed-canopy Forest in the Primary Forest of Northern Congo". Oryx. 36 (#1): 81–86. doi:10.1017/S0030605302000121.

- Hoek, Yntze van der; Lustenhouwer Ivo; Jefferry Kathryn J.; Hooft Pim van (2012). "Potential Effects of Prescribed Savannah Burning on the Diet Selection of Forest Buffalo (Syncerus Caffer Nanus) in Lope´ National Park, Gabon". African Journal of Ecology. 51 (#1): 94–101. doi:10.1111/aje.12010.

- Korte, Lisa M. (2008). "Habitat Selection at Two Spatial Scales and Diurnal Activity Patterns of Adult Female Forest Buffalo". Journal of Mammalogy. 89 (#1): 115–125. doi:10.1644/06-MAMM-A-423.1. S2CID 86366800.

- Korte, Lisa M. (2008). "Variation of Group Size Among African Buffalo Herds in a Forest-savanna Mosaic Landscape". Journal of Zoology. 275 (#3): 229–236. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2008.00430.x.

- Korte, Lisa M. (2009). "Herd-switching in Adult Female African Forest Buffalo Syncerus Caffer Nanus". African Journal of Ecology. 47 (#1): 125–127. Bibcode:2009AfJEc..47..125K. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.2008.00978.x.

- Melletti M.; Penteriani V.; Boitani L. (2007). "Habitat Preferences of the Secretive Forest Buffalo Syncerus Caffer Nanus in Central Africa" (PDF). Journal of Zoology. 271 (#2): 178–186. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2006.00196.x. hdl:10261/62369.

- Melletti, Mario; Penteriani Vincenzo; Mirabile Marzia; Boitani Luigi (2007). "Some Behavioral Aspects of Forest Buffalo (Syncerus Caffer Nanus): From Herd to Individual". Journal of Mammalogy. 88 (#5): 1312–1318. doi:10.1644/06-MAMM-A-240R1.1. hdl:10261/62519.

- Melletti, Mario; Penteriani, Vincenzo; Mirabile, Marzia; Boitani, Luigi (2008). "Effects of habitat and season on the grouping of forest buffalo resting places". African Journal of Ecology. 47: 121–124. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.2008.00965.x. hdl:10261/62295.

- Melletti, Mario; M. M. Delgado; Penteriani Vincenzo; Mirabile Marzia; Boitani Luigi (2010). "Spatial properties of a forest buffalo herd and individual positioning as a response to environmental cues and social behaviour". Journal of Ethology. 28 (#3): 421–428. doi:10.1007/s10164-009-0199-z. hdl:10261/62522. S2CID 31163978.

- Melletti M.; Burton J., eds. (2014). Ecology, Evolution and Behaviour of Wild Cattle. Implications for Conservation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-03664-2.