Natzweiler-Struthof was a Nazi concentration camp located in the Vosges Mountains close to the villages of Natzweiler and Struthof in the Gau Baden-Alsace of Germany, on territory annexed from France on a de facto basis in 1940. It operated from 21 May 1941 to September 1944, and was the only concentration camp established by the Germans in the territory of pre-war France. The camp was located in a heavily forested and isolated area at an elevation of 800 metres (2,600 ft).

| Natzweiler-Struthof | |

|---|---|

| Nazi concentration camp | |

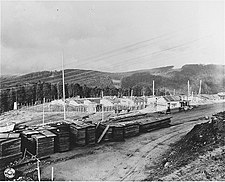

View of the camp after liberation | |

| Coordinates | 48°27′17″N 7°15′16″E / 48.45472°N 7.25444°E |

| Known for | Nacht und Nebel resistance fighters, Jewish skull collection |

| Location | Nazi Germany 1941–44 (de facto) (modern-day Bas-Rhin, France) |

| Operated by | the Nazi Schutzstaffel (SS) |

| Commandant | |

| Operational | May 1941 – September 1944 |

| Number of gas chambers | one from April 1943 |

| Inmates | mainly resistance fighters from occupied European nations |

| Number of inmates | 52,000 estimated[1] |

| Killed | 22,000 estimated[2] |

| Liberated by | French 1st Army, U.S. 6th Army Group, 23 November 1944 |

| Notable inmates | Boris Pahor, Trygve Bratteli, Charles Delestraint, Per Jacobsen, Asbjørn Halvorsen, Diana Rowden, Vera Leigh, Andrée Borrel, Sonya Olschanezky |

| Notable books | Necropolis, The Names of the Numbers, The Nazi Hunters by Damien Lewis |

| Website | www |

About 52,000 prisoners were estimated to be held there during its time of operation.[1][3] The prisoners were mainly from the resistance movements in German-occupied territories. It was a labor camp, a transit camp and, as the war went on, a place of execution. Some died of exhaustion and starvation – there were an estimated 22,000 deaths at the camp and its network of subcamps.[4] Many prisoners were moved to other camps; in particular, in 1944 the former head of Auschwitz concentration camp was brought in to evacuate the prisoners of Natzweiler-Struthof to Dachau as the Allied armies approached. Only a small staff of Nazi SS personnel remained when the camp was liberated by the French First Army under the command of the U.S. Sixth Army Group on 23 November 1944.[5]

The anatomist August Hirt made a Jewish skull collection, whose purpose was to portray Jews as racially inferior, at the camp. A documentary movie was made about the 86 named men and women who were killed there for that project.[clarification needed] Some of the people responsible for atrocities in this camp were brought to trial after the war ended.

The camp is preserved as a museum in memory of those held or killed there. The European Centre of Deported Resistance Members is located at this museum, focusing on those held. A monument to the departed stands at the site. The present museum was restored in 1980 after damage by neo-Nazis in 1976. Among notable prisoners, the writer Boris Pahor was interned in Natzweiler-Struthof and wrote his novel Necropolis based on his experience.

Background

editIn 1940, Germany invaded and occupied France, including Alsace. That region, adjacent to the German border, was chosen for full Germanization and was annexed to Gau Baden-Alsace. On 2 July 1940, two weeks after the fall of the nearby city of Strasbourg, an internment camp was set up near Schirmeck which existed throughout the war but was never part of the concentration camp system. The Natzweiler-Struthof main camp on 1 May 1941 was established nearby at Natzweiler in the Bruche valley, due to its proximity to a quarry.[6]

Operations

editThe construction of Natzweiler-Struthof was overseen by Hans Hüttig in the spring of 1941, in a heavily forested and isolated area at an elevation of 800 metres (2,600 ft). The camp operated between 21 May 1941 and the beginning of September 1944, when the SS evacuated the surviving prisoners on a "death march" to Dachau, with only a small SS unit keeping the camp's operations.[2]

On 23 November 1944, this camp with its small staff was discovered and liberated by the French First Army as part of the U.S. Sixth Army Group,[2] on the same day that the city of Strasbourg was liberated by the Allies. Through 1945, Natzweiler-Struthof had a complex of about 70 subcamps or annex camps.[7] (For the system of subcamps see List of subcamps of Natzweiler-Struthof.)

Initial focus and later actions

editThe total number of prisoners reached 52,000 over the three years, of 32 nationalities.[3] Inmates originated from various countries, including Poland, the Soviet Union, the Netherlands, France, Nazi Germany, Slovene-speaking parts of Yugoslavia and Norway. The camp was specially set up for Nacht und Nebel prisoners, in most cases, people of the resistance movements. It was a labor camp and a transit camp, as many prisoners were sent to other Nazi concentration camps before the final evacuation. As the war continued, it became a death camp as well. Some people died of exhaustion from the work they had to do while starving. Deaths have been estimated at 22,000 at the main camp and the subcamps.[4]

Interned prisoners provided forced labor for the Wehrmacht war industry, through contracts with private industry. The work was done mainly at the numerous annex camps, some of them located in mines or tunnels to protect them from Allied air raids. Work, hunger, darkness and lack of health care caused many epidemics; mortality rates could reach 80%.[7] Some worked in quarries, but many worked in the arms industry at various subcamps. Daimler-Benz moved its aircraft engine factory from Berlin to a gypsum mine near the Neckarelz annex camp. The disused autobahn Engelberg Tunnel in Leonberg, near Stuttgart, was used by the Messerschmitt Aircraft Company which eventually employed 3,000 prisoners in forced labor. Another annex camp at Schörzingen was established in February 1944 to extract crude oil from oil shale. The total number of prisoners at all of the Natzweiler subcamps was an estimated 19,000 of whom between 7,000 and 8,000 were in the main camp at Natzweiler.[5]

The camp held a crematorium and a jury rigged gas chamber outside the main camp, which was not used for mass extermination but for selective extermination, as part of the human experimentation programs, in particular on the problems of fighting a war, like typhus among the troops.

Doctors Otto Bickenbach and Helmut Rühl were accused of crimes committed at this camp. Hans Eisele was also stationed in this camp for a time. August Hirt committed suicide in June 1945; his suicide was unknown for many years, and he was tried in absentia in 1953 at Metz for his war crimes, including the Jewish skull collection, begun at Auschwitz, continued at Natzweiler-Struthof, and at the Reichsuniversität Straßburg.[8]

Some prisoners were executed directly, by hanging, by gunshot or by gas. The female prisoner-population in the camp was small, and only seven SS women served in Natzweiler-Struthof camp (compared to more than 600 SS men) and 15 in the Natzweiler complex of subcamps. The main duty of the female supervisors in Natzweiler was to guard the few women who came to the camp for medical experiments or to be executed. The camp also trained several female guards who went to the Geisenheim and Geislingen subcamps in western Germany.

Leo Alexander, the medical advisor at the Nuremberg trials, stated that some children were murdered at Natzweiler-Struthof for the sole purpose of testing poisons for inconspicuous executions of Nazi officials and prisoners.[9] Such executions of[who?] took place at Bullenhuser Damm.[citation needed]

The camp became a war zone in late summer 1944, and was evacuated in early September 1944. Prior to the evacuation of the camp, 141 prisoners were shot dead on 31 August – 1 September 1944. The 70th anniversary of this execution of those who resisted Nazi occupation was commemorated at the museum in 2014.[3]

Notable prisoners

editFour female British SOE agents were executed together on 6 July 1944: Diana Rowden, Vera Leigh, Andrée Borrel and Sonya Olschanezky.[10] Brian Stonehouse of the British SOE and Albert Guérisse, a Belgian escape line leader, witnessed the arrival of the four women and the events leading up to their execution and cremation; both men testified to the executions of the four women in post-war trials.[11] The two men were sent to Dachau, where they were liberated. Roger Boulanger writes of the four British SOE women executed under the supervision of Dr. Plaza and Dr. Rhode, in his section on Capital Punishment (Les exécutions capitales), as to the intent of the RSHA of Berlin, Reichssicherheitshauptamt, to have them disappear with no trace, as their names were not recorded as being at this camp. Stonehouse later sketched the four women which aided in their identification.[12][13]

Charles Delestraint, leader of the Armée Secrète, was detained at Natzweiler-Struthof, then was executed by the Gestapo in Dachau days before that camp was liberated and the war ended.[14] Henri Gayot, a member of the French Resistance who was interned at Struthof between April and September 1944, documented his ordeal in drawings which are now in the Struthof Concentration Camp Museum.[13][15]

Bishop Gabriel Piguet, the Roman Catholic Bishop of Clermont-Ferrand, was interned at Natzweiler before being transferred to the Priest Barracks of Dachau Concentration Camp. He is honored as a Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem, Israel's Holocaust Memorial, for hiding Jewish children in Catholic boarding schools.[16]

Two British Royal Air Force airmen (Flying Officer Dennis H. Cochran, and Flight Lieutenant Anthony "Tony" R. H. Hayter) who were involved in "The Great Escape" and murdered by the Gestapo after re-capture,[17] were cremated at Natzweiler-Struthof.

British bomber Sergeant Frederic ("Freddie") Habgood was hanged at this camp, after his Lancaster bomber crashed in Alsace on 27 July 1944 and he was betrayed to the Nazis by a local woman.[18] Two died as a result of the crash, three survived as prisoners of war in a camp in Poland, one returned to England with the help of the resistance, and Mr Habgood was hanged on 31 July 1944. His death was acknowledged as a war crime in 1947 and his family was informed, but the most personal evidence of his presence there, a silver bracelet with his name on it, emerged from the soil in July 2018, as an area with flowers was being watered by a volunteer.[18]

In his memoirs titled Moi, Pierre Seel, déporté homosexuel, Pierre Seel, who served a sentence at the neighboring camp of Schirmeck, tells that he took part in the construction of the Struthof concentration camp, in the context of his forced labor tasks.[19]

Notable Norwegian prisoners at Natzweiler include newspaper editor and Labour Party politician Trygve Bratteli who later went on to become Prime Minister of Norway, and former footballer Asbjørn Halvorsen who had previously played in Germany for Hamburger SV. Both were imprisoned at Natzweiler for distribution of illegal newspapers in German-occupied Norway. In total, 504 Norwegians were imprisoned at Natzweiler. Only 266 of them returned home alive.[20]

The Slovene novelist Boris Pahor was imprisoned at the camp in 1944. Pahor was later transported to Dachau camp and other camps until finally liberated in Bergen-Belsen. After the war he wrote the novel Necropolis about his experiences in the camp. The novel was later translated into numerous other European languages.[21]

List of personnel

editThe camp had five commandants and numerous doctors in its history.[22][23]

Commanders (Commandants)

edit- SS-Hauptsturmführer Hans Huttig

- SS-Sturmbannführer Egon Zill

- SS-Hauptsturmführer Josef Kramer

- SS-Sturmbannführer Fritz Hartjenstein

- SS-Hauptsturmführer Heinrich Schwarz

SS Doctors

edit- SS-Hauptsturmführer Kurt aus dem Bruch

- SS-Hauptsturmführer Karl Babor

- SS-Hauptsturmführer Heinz Baumköther

- SS-Hauptsturmführer Max Blancke

- SS-Obersturmführer Franz von Bodmann

- SS-Obersturmführer Hans Eisele

- SS-Obersturmführer Herbert Graefe

- SS-Sturmbannführer Richard Krieger

- SS-Obersturmführer Georg Meyer

- SS-Hauptsturmführer Heinrich Plaza

- SS-Hauptsturmführer Elimar Precht

- SS-Untersturmführer Andreas Rett

- SS-Untersturmführer Werner Rohde

- SS-Hauptsturmführer Gerhard Schiedlausky

- SS-Obersturmführer Siegfried Schwela

Private firms using inmate labor

editThe following private firms used Natzweiler-Struthof camp's inmates for labor in their factories:[24][25]

- Allgemeine Elektrizitäts Gesellschaft (AEG)

- Adlerwerke AG (formerly Adlerwerke vorm. Heinrich Kleyer)

- Bayerische Motorenwerke AG (BMW)

- Berger

- Bergwerks Industrie AG

- Daimler-Benz AG

- Friedrich Krupp Ironworks

- Gruen & Bulfinger

- Henkel & Cie

- Heinkel Flugzeugwerke, aircraft factory, Zuffenhausen

- Kessler Factory

- Koch & Mayer

- Messerschmitt AG

- Röchling Group[26]

Jewish skull collection

editThe Jewish skull collection was an attempt by the Nazis to create an anthropological display to showcase the alleged racial inferiority of the "Jewish race" and to emphasize the status of Jews as Untermenschen ("sub-humans"), in contrast to the Germanic Übermenschen ("super-humans") Aryan race which the Nazis considered to be the "Herrenvolk" (master race). The people who were to serve as best examples of the "Jewish race" were selected from people at the Auschwitz camp, then brought to Natzweiler-Struthof both to eat well and then to be murdered by gas, and their corpses brought to the Anatomy Institute of at the Reich University of Strasbourg (Reichsuniversität Straßburg) in the annexed region of Alsace, a project of great scope. Some initial study of the corpses was performed, but the progress of the war stalled completion of the collection.

The collection was sanctioned by Reichsführer of the SS Heinrich Himmler, and under the direction of August Hirt with Rudolf Brandt and Wolfram Sievers who was responsible for procuring and preparing the corpses as part of his management of the Ahnenerbe (the National Socialist scientific institute that researched the archaeological and cultural history of the hypothesized Aryan race). In a 2013 documentary by Sonia Rolley and others, two historians remark that "Hirt is one of the most absolutely criminal of National Socialist ideology," adds the historian Yves Ternon. "The project itself, continues Professor Johann Chapoutot, is an example of this investment of politics by science, or science by politics that is Nazism."[27]

In 1943, the inmates selected at Auschwitz were transported to Natzweiler-Struthof. They spent two weeks eating well in barracks there in Block 13, so they would be good specimens of normal size. The deaths of 86 inmates were, in the words of Hirt, "induced" at a jury rigged gassing facility at Natzweiler-Struthof on several days in August and their corpses, 57 men and 29 women, were sent to Strasbourg for study. Natzweiler-Struthof was considered the better place for gassing the selected victims (better than at Auschwitz), as they would die one by one, with no damage to the corpses, and Natzweiler-Struthof was at Hirt's disposal.[27] Josef Kramer, acting commandant of Natzweiler-Struthof (who was a Lagerführer at Auschwitz and the last commandant of Bergen Belsen) personally carried out the gassing of 80 of the 86 victims at Natzweiler-Struthof.[28][29]

The next part of the process for this "collection" was to bring the corpses to the Reichs University, where Hirt's plan was to make anatomical casts of the bodies. Photos of the corpses as found by the Allies who saw them in the Reichs University make the totality of the strange project quite real.[27][30] The next step after making the casts was to have been reducing them to skeletons. Neither of those steps, making the casts nor reducing the corpses to skeletons, was carried out. In 1944, with the approach of the Allies, there was concern over the possibility that the corpses could be discovered. In September 1944, Sievers telegrammed Brandt: "The collection can be defleshed and rendered unrecognizable. This, however, would mean that the whole work had been done for nothing – at least in part – and that this singular collection would be lost to science, since it would be impossible to make plaster casts afterwards." And so it was left, as the camp was evacuated in September 1944, and the human remains were left at a room in the Reichs University of Strasbourg.[31]

Two anthropologists, who were both members of the SS, Hans Fleischhacker and Bruno Beger, along with Wolf-Dietrich Wolff, were accused of making selections at Auschwitz of Jewish prisoners for Hirt's collection of 'racial types', the man who devised the project of the Jewish skull collection. Beger was found guilty, although he was credited for pre-trial imprisonment and served no time.[32] Also named as associated with this project are doctor Karl Wimmer and the anatomist Anton Kiesselbach.[33] August Hirt, who conceived the project, was sentenced to death in absentia at the Military War Crimes Trial at Metz on 23 December 1953.[32] It was unknown at the time that Hirt had shot himself in the head on 2 June 1945 while in hiding in the Black Forest.[32]

For many years only a single victim, Menachem Taffel (prisoner no. 107969), a Polish-born Jew who had been living in Berlin, was positively identified through the efforts of Serge and Beate Klarsfeld. In 2003, Hans-Joachim Lang, a German professor at the University of Tübingen succeeded in identifying all the victims, by comparing a list of inmate numbers of the 86 corpses at the Reichs University in Strasbourg, surreptitiously recorded by Hirt's French assistant Henri Henrypierre, with a list of numbers of inmates vaccinated at Auschwitz. The names and biographical information of the victims were published in the book Die Namen der Nummern (The Names of the Numbers).[34] Rachel Gordon and Joachim Zepelin translated the introduction to the book to English, at the web site where the whole book, including the biographies of the 86 people, is posted in German.[31] Lang recounts in detail the story of how he determined the identities of the 86 victims gassed for Hirt's project of the Jewish skull collection. Forty-six of these individuals were originally from Thessaloniki, Greece. The 86 were from eight countries in German-occupied Europe: Austria, Netherlands, France, Germany, Greece, Norway, Belgium and Poland.[32][35][36] The biographies of all 86 people are described in English on a web site set up by Lang.[37]

In 1951, the remains of the 86 victims were reinterred in one location in the Cronenbourg-Strasbourg Jewish Cemetery. On 11 December 2005, memorial stones engraved with the names of the 86 victims were placed at the cemetery. One is at the site of the mass grave, the other along the wall of the cemetery. Another plaque honoring the victims was placed outside the Anatomy Institute at Strasbourg's University Hospital.

In 2022, the gas chamber was reopened to the public, but the European Center for Deported Resistance Fighters (CERD), led by Guillaume d'Andlau, indicated that it did not want to: "celebrate the inauguration of this morbid place",[38] having " nothing to do with those intended for mass murder", specifying that "it is a symbolic place for the camp and its activities in connection with the Reichsuniversität Straßburg"[39] which is perceived as a lack of sensitivity towards mourners.[40]

Post-war criminal trials

editThe first camp commandant, Hans Hüttig, was sentenced to life in prison on 2 July 1954 by a French military court in Metz. In 1956, he was released from detention after being imprisoned for eleven years.[41]

Josef Kramer, the former commandant of the camp during the time of the Jewish skull collection project, was arrested at Bergen-Belsen concentration camp on 17 April 1945 and tried at Lüneburg in the British-occupied sector for other crimes committed in Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen. He was sentenced on 16–17 November 1945 and was hanged at Hamelin prison on 13 December 1945.[42]

The commandant of Natzweiler at the time that four female resistance agents were executed, Fritz Hartjenstein and five others were tried by a British war crimes court at Wuppertal, from 9 April to 5 May 1946. All of the accused were found guilty; of these, three were sentenced to death and two hanged. Hartjenstein's death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment on 1 June 1946. However, he was tried a second time by the British for hanging a POW who was a member of the Royal Air Force. He died of a heart attack while awaiting execution on 20 October 1954.[43][44]

Those tried at Wuppertal were:[45]

- Franz Berg: death sentence (executed by hanging 11 October 1946)

- Kurt Geigling: 10 years imprisonment

- Josef Muth: 15 years imprisonment

- Peter Straub: death sentence (executed by hanging 11 October 1946)

- Magnus Wochner: 10 years imprisonment

- Fritz Hartjenstein (commandant): death sentence, commuted to life (Wuppertal), death sentence by British (Rastatt), death sentence by French Court (Metz), died before sentence was carried out

Magnus Wochner was also implicated in the Stalag Luft III murders and was listed among the accused.[44] Heinrich Ganninger, adjutant and deputy of commander Fritz Hartjenstein, committed suicide in Wuppertal prison in April 1946 before his trial. He was accused of having murdered four British female spies.[44][11]

Heinrich Schwarz was tried separately at Rastatt in connection with atrocities committed during his tenure as commandant of Natzweiler-Struthof. He was sentenced to death and subsequently shot by a firing squad near Baden-Baden on 20 March 1947.[46][42]

Post-war history, museum and monument

editDuring the night of 12–13 May 1976, neo-Nazis burned the camp museum, with the loss of important artifacts. Structures were rebuilt, placing the artifacts that survived the fire as they were found originally. The reconstructed camp museum was officially opened on 29 June 1980. The European Centre of Deported Resistance Members, a new structure at the site, opened in November 2005, and at the same time, "the museum was entirely redesigned to focus solely on the history of Natzweiler concentration camp and its subcamps."[47]

A dramatic monument (including a bronze figure supine and emaciated) stands in Pere Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

Documentary films

editA documentary film was shown in 2014 about the 86 people who were murdered in the camp and whose remains were later identified by name, as described above in The Jewish skull collection section.[48] The film "The names of the 86" (French: Le nom des 86) was directed by Emmanuel Heyd and Raphael Toledano (Dora Films).[49]

Another documentary was made about the skull project in 2013, titled Au nom de la race et de la science, Strasbourg 1941–1944 (English: In the name of Race and Science, Strasbourg 1941–1945). Its goal was to explain what happened at Reich University of Strasbourg, at Natzweiler-Struthof, in the strange use of science in this Nazi project to eliminate the Jews, but keeping some remains for history and science, the project never fully completed.[27]

In the 2019 BBC One documentary The Man Who Saw Too Much Alan Yentob traces the story of 106-year-old Boris Pahor, believed to be the oldest known survivor of the Nazi concentration camps at the time.[50]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "The deportees of KL-Na". Struthof – the Site of the former Natzweiler concentration camp. Centre européen du résistant déporté. Archived from the original on December 3, 2020. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Introduction to the history of the camp | STRUTHOF". Struthof.fr. Archived from the original on June 3, 2018. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ^ a b c Buonasorte, Alvezio (September 1, 2014). "Struthof: Commémoration des exécutions de 141 résistants" [Commemoration of the executions of 141 resistance fighters at Struthof] (in French). Natzwiler, France: l'Alsace. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ a b "Struthof: Some data". Centre européen du résistant déporté. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ a b "Natzweiler-Struthoff Concentration Camp". Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team. Retrieved September 20, 2015.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos volume one, Natzweiler-Struthof main camp, p. 1004

- ^ a b "KL-Natzweiler annex camps 1942–1945". Struthof – the Site of the former Natzweiler concentration camp. Centre européen du résistant déporté. Archived from the original on June 3, 2018. Retrieved September 20, 2015.

- ^ Breeden, Aurelien (July 24, 2022). "A French University Confronts Medical Crimes and Its Nazi Past". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 24, 2022.

- ^ Alexander, Leo (1948). "War Crimes and Their Motivation: The SocioPsychological Structure of the SS and the Criminalization of a Society". Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology. 39 (3): 326.

As a means of further camouflage so that the SS at large would not suspect the purpose of these experiments, the preliminary tests for the efficacy of this method were performed exclusively on children imprisoned in the Natzweiler concentration camp.

- ^ Charlesworth, Lorie (Winter 2006). "2 SAS Regiments, War Crimes Investigations, and British Intelligence: Intelligence Officers and the Natzweiler Trial". The Journal of Intelligence History. 6 (2): 13–60. doi:10.1080/16161262.2006.10555131. S2CID 156655154.

- ^ a b Law Reports of Trials of War Criminals, Vol. V (1948). Case No. 31. Trial Of Werner Rohde And Eight Others, British Military Court, Wuppertal, Germany, 29th May-1st June, 1946 (PDF). London, UK: The United Nations War Crimes Commission. p. 54.

- ^ Boulanger, Roger (2000). "L'historique du camp de Natzweiler-Struthof" [The history of the Natzweiler-Struthof camp]. CRDP Champagne-Ardenne. Archived from the original on November 23, 2007. Retrieved September 19, 2015.

C'était une fonction spécifique du camp. Les victimes devaient disparaître sans laisser de traces.[It was a specific function of the camp. The victims were to disappear without a trace.]

- ^ a b Helm, Sarah (2005). A Life in Secrets. New York: Doubleday. pp. 216–219. ISBN 9780385508452.

- ^ "Charles Delestraint" (in French). Le Musée de l'Ordre de la Libération. December 14, 2001. Archived from the original on May 22, 2009. Retrieved September 20, 2015.

il est envoyé au camp de Natzwiller-Struthof, en Alsace, et devient un déporté "Nacht und Nebel", de la catégorie de ceux que l'on doit faire disparaître dans "la nuit et le brouillard". . . . Les alliés approchant, il est transféré au début du mois de septembre 1944 à Dachau, près de Munich. Mais un ordre, probablement signé Kaltenbrünner, le condamne à disparaître avant l'arrivée des alliés. Le 19 avril 1945, dix jours seulement avant l'arrivée des Américains, il est lâchement abattu d'une balle dans la nuque avant d'être incinéré au crématoire du camp.[English: "he was sent to Natzwiller-Struthof camp in Alsace, and became a "Nacht und Nebel" prisoner, the category of those who must disappear into "the night and fog". . . The Allies approached, he was transferred at beginning of September 1944 to Dachau, near Munich. But an order, probably signed Kaltenbrunner, condemned him to disappear before the arrival of the Allies. On April 19, 1945, just ten days before the arrival of the Americans, he was cowardly shot in the neck before being cremated in the camp crematorium."]

- ^ "Collections Search - United States Holocaust Memorial Museum". collections.ushmm.org. Retrieved 2024-11-25.

- ^ "The Righteous Among The Nations". YadVashem.org. Retrieved September 20, 2015.

- ^ The United Nations War Crimes Commission (1949). Law Reports of Trials of War Criminals, vol. XI (PDF). London, UK: His Majesty's Stationery Office. pp. 41–42. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

- ^ a b Nicholls, Dominic (December 25, 2018). "Family of World War Two Lancaster bomber reunited with his bracelet 74 years after it rose to surface of concentration camp ash pit". The Telegraph. Retrieved January 6, 2019.

- ^ Seel, Pierre (April 1, 1994). Moi, Pierre Seel, déporté homosexuel (English translation: I, Pierre Seel, deported homosexual) (in French). Calmann-Lévy. ISBN 978-2702122778.

- ^ Kronikk: Den glemte generalen (in Norwegian)

- ^ Benjamin Ivry (2 June 2022). "How a once-neglected Slovenian writer survived the Nazis camps to live to 108 – The Forward". Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ MacLean, French L. (1999). The camp men: the SS officers who ran the Nazi concentration camp system. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 0764306367.

- ^ "KZ-Katzweiler Men". Axis History Forum. Retrieved September 19, 2015.

- ^ "In Re Holocaust Victim Assets Litigation (Swiss Banks) Special Master's Proposal" (PDF). September 11, 2000. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ "Elenco delle aziende e dei campi di concentramento ricorrendo al lavoro forzato" [List of companies and concentration camps using forced labor]. Centro studi Schiavi di Hitler (in Italian). Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ Militärregierung der Französischen Besatzungszone in Deutschland, Oberstes Gericht (1949). Unterlagen zu den Röchling-Prozessen: Urteile des General-Gerichts und des Obersten Gerichts (in German). Mannheim. p. 44.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d Bernas, Anne (October 24, 2014). "Un documentaire sur un crime nazi méconnu primé à Waterloo" [A documentary about a misunderstood Nazi crime winning at Waterloo] (in French). RFI les voix du monde. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ^ The Belsen Trial: Trial of Josef Kramer and 44 Others from 'Law Reports of Trials of·War Criminals' (PDF). Vol. II. London: The United Nations War Crimes Commission. 1947. pp. 39–40. Retrieved October 15, 2015.

Under cross-examination he admitted having gassed 80 prisoners previously at Natzweiller camp.

- ^ "Kramer Persists in Denying Guilt". The New York Times. October 10, 1945. p. 8. Retrieved September 19, 2015.

- ^ Rolley, Sonia; Ramonet, Axel and Tancrède (directors) (May 2, 2013). Au nom de la race et de la science 1941–1944 (3/4) [In the name of Race and Science 1941–1944 (3/4)] (documentary) (in French). Alsace, France: Temps Noir. 10 minutes in. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ^ a b "Die Namen Der Nummern" [The names of the numbers]. Translated by Rachel Gordon; Joachim Zepelin. Berlin. 2007. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Lang, Hans-Joachim (August 19, 2004). "Skelette für Straßburg Eines der grausigsten Wissenschaftsverbrechen des "Dritten Reiches" ist endlich aufgeklärt" [Skeletons for Strasbourg: One of the most gruesome crimes of science in the "Third Reich" is finally cleared]. Die Zeit (in German). Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- ^ Mitscherlich, Fred Mielke: Medicine without humanity: documents of the Nuremberg Doctors Trial, Frankfurt am Main 1995, p. 216

- ^ Lang, Hans-Joachim (August 31, 2004). Die Namen der Nummern: Wie es gelang, die 86 Opfer eines NS-Verbrechens zu identifizieren [The names of the numbers: How it was possible to identify the 86 victims of a Nazi crime] (in German) (hardback ed.). Hoffmann + Campe Vlg GmbH. ISBN 3-455-09464-3.

- ^ Lang, Hans-Joachim. "[Victims of medical research at Natzweiler, from "Die Namen der Nummern: Eine Initiative zur Erinnerung an 86 jüdische Opfer eines Verbrechens von NS-Wissenschaftlern"] (ID: 20733)". US Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- ^ Lang, Hans-Joachim. "The Names of the Numbers: In Memoriam of 86 Jewish People who Fell Victim to the Nazi Scientists". Tübingen, Germany. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ^ Lang, Hans-Joachim. "The Names of the Numbers: The Courses of 86 Lives". Tübingen, Germany. Archived from the original on June 3, 2020. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ^ "Bas-Rhin : La chambre à gaz du camp de concentration du Struthof, témoin de l'horreur nazie" [Bas-Rhin: The gas chamber of the Struthof concentration camp, witness to the Nazi horror]. www.leparisien.fr. 25 November 2022.

- ^ "Alsace: Le camp de concentration du Struthof jusqu'au bout de son histoire" [Alsace: The Struthof concentration camp until the end of its history]. www.lefigaro.fr. 28 November 2022.

- ^ "Im KZ Natzweiler-Struthof wurden auch Morde des Rassenwahns begangen" [Racial murders were also committed in the Natzweiler-Struthof concentration camp]. www.badische-zeitung.de. 25 November 2022.

- ^ Thompson, David (2002). "Huettig, Hans". A Biographical Dictionary of War Crimes Proceedings, Collaboration Trials and Similar Proceedings Involving France in World War II. Grace Dangberg Foundation, Inc. Archived from the original on October 29, 2009. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- ^ a b "The trials". Struthof – the Site of the former Natzweiler concentration camp. Centre européen du résistant déporté. Retrieved September 20, 2015.

- ^ "Friedrich "Fritz" Hartjenstein". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

Hartjenstein's postwar fate consisted of many trials. First, he was arrested by the British and sentenced to life imprisonment on June 1, 1946, at Wuppertal for executing four resistance members. Then he was again tried by the British for hanging a POW who was a member of the Royal Air Force and sentenced to death by firing squad on June 5 of that year. He was then extradited to France, where he was tried for his crimes at Natzweiler and sentenced to death. He died of a heart attack while awaiting execution on October 20, 1954.

- ^ a b c Andrews, Allen (1976). Exemplary Justice. Corgi Books. ISBN 0-552-10800-6.

- ^ "Nazi War Crimes Trials: Natzweiler Trial". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

- ^ White, Joseph Robert (August 26, 2004). "Even in Auschwitz . . . Humanity Could Prevail:British POWs and Jewish Concentration-Camp Inmates at IG Auschwitz 1943–1945". In Boyne, Walter J. (ed.). Today's Best Military Writing: The Finest Articles on the Past, Present, and Future of the U.S. Military (First ed.). Forge Books. p. 179. ISBN 0-7653-0887-8.

- ^ "The KL-Natzweiler museum". Struthof – the Site of the former Natzweiler concentration camp. Centre européen du résistant déporté. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- ^ "Le Nom des 86" [The Names of the 86]. Dora Films. 2014. Archived from the original on February 20, 2015. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- ^ "Le Nom des 86, DVD" [The Names of the 86, DVD]. Dora Films. 2014. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- ^ "BBC One – The Man Who Saw Too Much". BBC. 27 Jan 2022. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

Further reading

edit- Steegmann, Robert (2005). Struthof : le KL-Natzweiler et ses kommandos : une nébuleuse concentrationnaire des deux côtés du Rhin; 1941–1945 (in French). Strasbourg: Nuée Bleue. ISBN 2-7165-0632-9.

- Inmate accounts include

- Bakels, Floris (1977). Nacht und Nebel; mijn verhaal uit Duitse gevangenissen en concentratiekampen [Nacht und Nebel; my story in German prisons and concentration camps]. Elsevier. ISBN 90-435-0366-5.

- Bratteli, Trygve (1995) [1988]. Fange i natt og tåke [Prisoner in the night and fog] (in Norwegian) (2nd ed.). Oslo: Tiden. ISBN 82-10-03172-4., memoirs of the former prime minister of Norway

- Harthoorn, Willem Lodewijk (2007). Verboden te sterven [Forbidden to die]. Van Gruting. ISBN 978-90-75879-37-7.

- Ottosen, Kristian (1995) [1989]. Natt og tåke - Historien om Natzweiler-fangene [Night and fog - History of Natzweiler prisoners] (in Norwegian) (2nd ed.). Oslo: Aschehoug. ISBN 82-03-26076-4., written as an historical account by a former inmate, based on interviews and research

- Pahor, Boris (2010) [1967]. Necropolis. Champaign, Illinois: Dalkey Archive Press. ISBN 978-1564786111.

- Piersma, Hinke (2006). Doodstraf op termijn [Death penalty in time]. Walburg Pers. ISBN 90-5730-442-2.

- Recent research identified the 86 people murdered for the Jewish skull collection

- Lang, Hans-Joachim, The names of the numbers. How I succeeded in identifying the 86 victims of a NAZI crime. Hoffmann & Campe, Hamburg 2004, ISBN 978-3-455-09464-0.

External links

edit- Struthof official site

- The Names of the Numbers – A Project of Hans-Joachim Lang. List of all 86 victims of the Jewish Skeleton Collection (in German – also in English, French, Greek, Hebrew, Dutch, Norwegian and Polish)

- Independent researcher Diana Mara Henry's site

- Memoir by KLNA Survivor Joseph Scheinmann aka Andre Peulevey Archived 2021-07-26 at the Wayback Machine

- History of the Natzweiler-Struthof Camp by Roger Boulanger, camp survivor (in French)

- Au nom de la race et de la science 1941–1944 (1/4) on YouTube

- Au Nom De La Race Et De La Science Documentaire Entier Français on YouTube