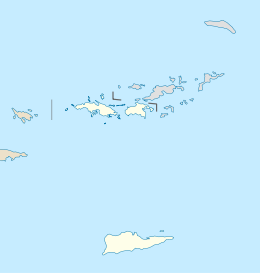

Saint John, U.S. Virgin Islands

Saint John (Danish: Sankt Jan; Spanish: San Juan) is one of the Virgin Islands in the Caribbean Sea and a constituent district of the United States Virgin Islands (USVI), an unincorporated territory of the United States.

Nickname: Love City | |

|---|---|

Trunk Bay, Saint John, U.S. Virgin Islands | |

Satellite image of Saint John | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Caribbean Sea |

| Coordinates | 18°20′N 64°44′W / 18.333°N 64.733°W |

| Archipelago | Virgin Islands, Leeward Islands |

| Area | 20[1] sq mi (52 km2) |

| Administration | |

| Insular area | |

| District | Saint John |

| Largest settlement | Cruz Bay (pop. 2,706) |

| Administrator | Shikima Jones[2] |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 3,881 (2020 census[3]) |

| Pop. density | 74.6/km2 (193.2/sq mi) |

Saint John (50 km2 (19 sq mi)) is the smallest of the three main US Virgin Islands.[4] It is located about four miles east of Saint Thomas, the location of the territory's capital, Charlotte Amalie. It is also four miles southwest of Tortola, part of the British Virgin Islands. Its largest settlement is Cruz Bay with a population of 2,652.[5] Saint John's nickname is Love City.[6]

Since 1956, approximately 60% of the island is protected as Virgin Islands National Park, administered by the United States National Park Service.[7] The economy is based predominantly on tourism and related trade.[8]

Saint John is 50.8 km2 (19.6 sq mi) in area with a population of 3,881 (2020 census).[5] As of the 2020 U.S. census, the population of the US Virgin Islands territory was 87,146,[5] comprising mostly persons of Afro-Caribbean descent.[9]

History

editPetroglyphs and artifacts found at Cinnamon Bay indicate a Taíno presence on Saint John from about 700 to the late 15th century.[10]

Christopher Columbus sailed past Saint John on his second voyage in 1493, but did not come ashore. He named the northern Virgin Islands Las Once Mil Virgenes.[10]: 24

Colonization and settlement

editThe Danish West India Company resettled Saint Thomas in 1671,[11] and an African slave market was established in 1673. Saint John was claimed as a part of the British Leeward Islands in 1684 when it was leased to two English merchants from Barbados, yet they were removed by Governor Stapleton. It was uninhabited when 20 Danish planters came over from Saint Thomas in 1717, and the island was claimed again by Denmark in 1718.[12][13][14] They grew sugar cane, cotton, and other crops. Annaberg sugar plantation was built in 1731, and became one of the island's largest sugar producers by the 19th century. By 1733, there were 109 plantations on the island, 21 of which were producing sugar. The islands were made a crown colony in 1754,[10]: 24 and the British relinquished their claims to the island to the Danish in 1762.[13]

The 1733 slave insurrection on St. John started when a small group of slaves entered Fort Frederiksvaern, on Fortsberg Hill in Coral Bay, with cane bills concealed within bundles of wood. The slaves, led by those formerly from Akwamu, overpowered and killed 5 of the 6 soldiers within the Danish fort. Firing the fort's cannon, the signal was given for the start of a six-month revolt, which only ended when French troops were brought in from Martinique.[10]: 68–69

Instead of submitting to captivity and slavery, more than a dozen men and women, including Breffu, one of the leaders,[15] shot and killed themselves before the French forces reached them.

Moravian Brethren built the first church at Emmaus in 1749. Cruz Bay was established in 1766, and includes The Battery.[10]: 25

By 1804, the slave population reached a peak of 2,604. Denmark emancipated the slaves in 1848, and by 1850, many of the plantations were abandoned. By 1901, Saint John's population was 925,[16] and the last sugar factory ceased operation in 1908.[10]: 24–26 Between 1845 and 1945, the population declined by 70%.[17]

Purchase

editIn 1917, during the First World War, the United States purchased the U.S. Virgin Islands for $25 million from the Danish government in order to establish a naval base. It was intended to prevent expansion of the German Empire into the Western Hemisphere. As part of the negotiations for this deal, the US agreed to recognize Denmark's claim to Greenland, which they had previously disputed.

During the 20th century, private investors acquired properties on the island, redeveloping some plantation houses as vacation resorts, such as Laurence Rockefeller's Caneel Bay Resort. The islands became popular and tourism and related service jobs developed as a major part of the economy.

Hurricane Irma

editIn September 2017, Saint John was hit by Hurricane Irma. The category 5 storm forced roughly half of the island's 4,500 residents to evacuate and caused power outages that lasted for months.[18]

Government

editSince 1917, the U.S. Virgin Islands are an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States. Its residents are U.S. citizens, but they cannot vote in presidential elections.

Until 1970, governors of the territory were appointed by the US president. Since that year, residents of the island have elected a territorial governor and lieutenant governor, and fifteen senators to the legislature, representing all three islands. Seven are elected from the district of Saint Croix, seven from the district of Saint Thomas and Saint John, and one senator at-large (who must be a resident of Saint John) are elected for two-year terms to the unicameral Virgin Islands Legislature.

Residents of the Virgin Islands also elect a delegate to the US Congress, who has non-voting status in that body.

Saint John has no local government; however, the Governor appoints an administrator for the island. Having no official powers, this figure acts more as an adviser to the Governor and as a spokesperson for the Governor's policies.

The main political parties in the U.S. Virgin Islands are the Democratic Party of the Virgin Islands, the Independent Citizens Movement (ICM), and the Republican Party of the Virgin Islands. Additional candidates run as independents.

Voting

editSaint John is divided into the following subdistricts (with population as per the 2020 U.S. Census):[5]

Activists filed a lawsuit on September 20, 2011 in the federal US District Court of the Virgin Islands seeking the right to be represented in Congress and to vote for U.S. president. The case is Civil No. 3:11-cv-110, Charles v. U.S. Federal Elections Commission et al. The case alleges the 1917 Congress, with all-white members, denied the right to vote to island residents due to racial discrimination, as the island had a majority of people of color. The case was dismissed on August 20, 2012.[19]

Economy

editThe main export of Saint John used to be sugar cane, which was produced in great quantity using African slave labor. However, this industry declined after the abolition of slavery, as it was dependent on slave labor to be profitable. In addition, in that period, it had to compete with sugar produced in other areas, including by the use of sugar beets in northern locations.[citation needed]

Tourism

editThe economy of Saint John is almost entirely dependent on tourism. The island has hundreds of rental villas as well as hotels and resorts. Numerous shops and restaurants serving both residents and tourists are located in Cruz Bay and Coral Bay.

Saint John is a popular stop for day and term boat charters from the United States Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, and the British Virgin Islands. Individual and group boat charters are widely available on Saint John and island hopping is a favorite local and visitor activity. Popular day excursions include bar hopping or snorkeling at Christmas Cove, Jost Van Dyke, Buck Island National Wildlife Refuge, Tortola, Norman Island, Virgin Gorda, Water Island, Lovongo Cay, Cooper Island, and Peter Island. Mooring and anchoring locations are available in most bays around Saint John for both day use and overnight stays.[20]

Virgin Islands National Park

editIn 1956, Laurance Rockefeller donated his extensive lands on the island to the United States' National Park Service, under the condition that the lands had to be protected from future development. The remaining portion, the Caneel Bay Resort, operates on a lease arrangement with the NPS, which owns the underlying land.

The boundaries of the Virgin Islands National Park include 75% of the island, but various in-holdings within the park boundary (e.g., Peter Bay) reduce the park lands to 60% of the island acreage.

Much of the island's waters, coral reefs, and shoreline have been protected by being included in the national park. This protection was expanded in 2001, when the Virgin Islands Coral Reef National Monument was created.

Transport

editWhile Saint John does not have an airport, the island is served by Cyril E. King Airport on nearby Saint Thomas. There used to be a seaplane base[21][22] in the town of Cruz Bay. Antilles Airboats provided regular service until it was sold by Maureen O'Hara.[23] The Virgin Islands Seaplane Shuttle also used to offer services to that seaplane base using Grumman Mallard air boats prior to Hurricane Hugo.[24][citation needed]

A ferry service runs hourly from Red Hook, Saint Thomas, thrice daily from Charlotte Amalie, Saint Thomas, and daily from Tortola; regular ferries also operate from Virgin Gorda, Jost Van Dyke and Anegada.[25]

Cars and cargo are transported to the island via barge. Two companies offer barge service between Red Hook, Saint Thomas and Cruz Bay, Saint John. The barges operate hourly during daylight hours. Although prohibited by Virgin Islands law,[26] some rental car companies allow their vehicles to use the car ferry.[27][28] This is because the U.S. District Court deemed the law to violate the Interstate Commerce Clause of the United States Constitution.[29] However, as of 2017, the unconstitutional law is still technically on the books, but the Government of the Virgin Islands does not enforce it. Car rental companies are located throughout Cruz Bay, most within easy walking distance of the ferry dock.

Taxis are widely available on Saint John to provide transport to beaches, hotels, and vacation villas. Water taxi service is also available from Dolphin Water Taxi.[30]

VITRAN public bus service runs hourly on weekdays between Cruz Bay and Salt Pond Bay via Centerline Road.

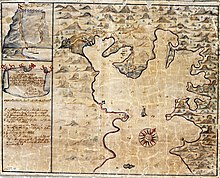

Major port town

editIn the colonial era, Coral Bay was the hub of economic activity on the island.[citation needed] Its natural port offered protection to the sailing ships of the day. In addition, it was an easy sail by smaller boats, with minimal tacking, to the nearby British Virgin Islands. Until the late 20th century, the residents of Coral Bay and East End had easier and more frequent access to Tortola than did those of either Cruz Bay or Saint Thomas.[citation needed]

Today, Cruz Bay is the port of entry to Saint John. Cargo and car barges use The Theovald Eric Moorehead Dock and Terminal. Domestic ferries use the Loredon L Boynes Dock in central Cruz Bay. International ferries use the United States Customs and Immigration dock at the Victor William Sewer Marine Facility.[31]

Cruise ships visit Cruz Bay regularly during the winter, although they must anchor and deliver guests via tender.[32] Saint John is also a popular day excursion for cruise ship passengers at port in Saint Thomas or Tortola.

The waters surrounding the US Virgin Islands are patrolled by United States Coast Guard cutters out of Miami, Florida, and San Juan, Puerto Rico.[citation needed]

Notable people

edit- Breffu, an Akwamu leader of the 1733 slave insurrection on St. John

- Myrah Keating Smith (1908–1994), a pioneering nurse and midwife

- John Campbell (born 1962), and daughter Jasmine Campbell (born 1991), alpine skiers, moved to US in 2000

- J. Robert Oppenheimer, the 'Godfather of the Atomic Bomb', starting in 1954, Oppenheimer lived for several months of each year on the island. From 1957 onwards, he owned a home on Gibney Beach.[33][34]

Education

editSt. Thomas-St. John School District operates schools for the island residents. Saint John has one public school, Julius E. Sprauve (pronounced "Sprow" and referred to as 'JESS'). Private and parochial schools include Gifft Hill School (formerly Pine Peace and Coral Bay), Saint John Christian Academy, Saint John Methodist School, and the Saint John Montessori School.[citation needed]

The only school that includes a high school is Gifft Hill, along with their programs in elementary and middle school. The only other middle school on the island is the 'JESS,' which also has an elementary program. The public high school for Saint John students is Ivanna Eudora Kean High School located in Red Hook, Saint Thomas.

In October, 2020, the Trump administration signed a non-binding preliminary agreement to pursue a land swap between the National Park Service and the U.S. Virgin Islands. The U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) and Government of the Virgin Islands (GVI) agreed to work together for 12 months to evaluate a proposed exchange that, if successful, would allow local officials to construct the first K-12 public school on Saint John. Public education on Saint John is currently only available through the eighth grade.[35] The National Park Service issued a Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI) on the Environmental Assessment (EA) for the potential land exchange. The final 45-day public comment period on the land exchange was opened from January 8, 2023 until Feb. 21, 2023.[36]

In literature

edit- Grandma Raised the Roof by Ethel Walbridge McCully. Author's own story of building her dream home on Saint John and defending it from being acquired by the National Park Service, in the early 1950s.[37]

Gallery

edit-

Turtle Bay Beach at Caneel Bay

-

Sunset at Turtle Bay

-

Reef Bay and Virgin Islands National Park from Cocoloba Point

-

Mid day Trunk Beach, Saint John Virgin Islands National Park

-

Gibney Beach on Hawksnest Bay

-

Trunk Bay

See also

edit- Outline of the United States Virgin Islands

- Index of United States Virgin Islands-related articles

- Bibliography of the United States Virgin Islands

- Flanagan Island

- Great Thatch

- List of people from the United States Virgin Islands

- National Register of Historic Places listings on Saint John

- Norman Island

- Piracy in the British Virgin Islands

- Virgin Islands Coral Reef National Monument

References

edit- ^ This is the figure given in the article at the on-line edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica. It is not the figure given by the government of the U.S. Virgin Islands on the St. John page of usvi.net, which reports the area to be 28 square miles. Other reliable sources report various figures closer to the Britannica figure. The Virgin Islands (United States) page at the United Nations Environment Programme's Island Directory gives the area as 50.0 square kilometers, equivalent to 19.3 square miles. A 1998 paper issued by the United States Geological Survey, Professional Paper 1631, reports the area as "about" 48 square kilometers, which is equivalent to 18.5 square miles (see page 1 of the paper). And although the U.S. Census Bureau does not report the areas of geographic entities, it does report their population densities (equal to the total population divided by the area). In the 2010 census, the population was reported as 4,170 (Table P1, "Total Population") and the population density was reported as 211.8 per square mile (Table P40, "Population Density"). Together, these figures imply an area of 19.7 square miles.

- ^ "Bryan Names Shikima Jones to St. John Administrator". St. John Source. February 5, 2019. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- ^ "2020 Island Areas Censuses: U.S. Virgin Islands". US Census Bureau. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- ^ "Where is the U.S. Virgin Islands: Geography". Virgin Islands.

- ^ a b c d "2020 Island Areas Censuses: U.S. Virgin Islands (Table 1. Population of the United States Virgin Islands: 2010 and 2020)" (PDF). US Census Bureau. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- ^ Jervis, Rick (September 3, 2018). "Hurricane recovery led by private groups on St. John one year later". USA Today. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ "Basic Information About Virgin Islands National Park". National Park Service. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ Austin, D. Andrew. "Economic and Fiscal Conditions in the U.S. Virgin Islands" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved August 14, 2018 – via fas.org.

- ^ "Explore Census Data: 2020 DECIA U.S. Virgin Islands Demographic Profile". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f U.S. Virgin Islands: a guide to national parklands in the United States Virgin Islands. Washington, D.C.: Division of Publications, National Park Service, U.S. Dept. of the Interior. 1999. pp. 53, 64–65. ISBN 0912627689.

- ^ "St. Thomas: island, United States Virgin Islands – Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- ^ Dookhan, Isaac. (1994). A history of the Virgin Islands of the United States. Kingston, Jamaica: Canoe Press. ISBN 976-8125-05-5. OCLC 31432296.

- ^ a b "St. John: History". VInow. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- ^ "St. John: island, United States Virgin Islands – Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- ^ Holly Kathryn Norton (2013). Estate by Estate: The Landscape of the 1733 St. Jan Slave Rebellion (PhD). Syracuse University. p. 90. ProQuest 1369397993.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). 1911.

- ^ Williams, Eric (January 1, 1945). "Race Relations in Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands". Foreign Affairs. Vol. 23, no. 2. ISSN 0015-7120.

- ^ "Battered by Hurricane Irma, thousands flee St. John island in path of the next storm". USA Today.

- ^ Charles v. U.S. Federal Election Commission et al., Docket Alarm, 2012-2015

- ^ "Quick Mooring Information - Virgin Islands National Park". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ "Airport codes Cruz Bay Seaplane Base in St John Island, Virgin Islands (VI)". airportsbase.org.

- ^ http://ourairports.com/airports/SJF/#lat=18.3315,lon=-64.79599999999999,zoom=14,type=Satellite,airport=SJF Cruz Bay Seaplane Base-OurAirports

- ^ "Maureen O'Hara left mark in Virgin Islands - News - Virgin Islands Daily News". virginislandsdailynews.com. Archived from the original on October 27, 2015. Retrieved June 6, 2022.

- ^ "Adventures of Cap'n Aux: Hurricane Hugo, Part 2". November 28, 2012.

- ^ "Virgin Islands Ferry Schedules". Virgin Islands. January 2, 2015.

- ^ "LexisNexis® Custom Solution: Virgin Islands Code Unannotated Research Tool". www.lexisnexis.com. p. 20 V.I.C. § 422. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- ^ "Budget Rent a Car". Retrieved May 1, 2017.

Yes, we allow our cars to go to St. John and here is the ferry schedules to St. John

- ^ "Amalie Car Rental St. Thomas FAQ". Retrieved May 1, 2017.

Yes! You Can Take the Vehicle to St. John

- ^ "Everett v. Schneider, 989 F. Supp. 720 (D.V.I. 1997)". Justia Law.

- ^ "Water Taxi in the Virgin Islands - Dolphin Water Taxi". www.dolphinshuttle.com. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ "The United States Virgin Islands' Airports and Seaports". Virgin Islands Port Authority. Archived from the original on October 9, 2015. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ "Ship Schedule - Port Availability". www.wico-vi.com. Archived from the original on August 22, 2016. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ Bird, Kai; Sherwin, Martin J. (2005). American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 566–569. ISBN 978-0-375-41202-8.

- ^ Bird & Sherwin 2005, p. 573

- ^ "Trump Administration Signs Agreement with U.S. Virgin Islands to Pursue a Land Exchange for New School on St. John". National Park Service. Office of Communications. October 22, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ "NPS Opens Final Public Comment Period and Releases Finding of No Significant Impact for Potential St. John Land Exchange". The Virgin Islands Consortium. January 12, 2023. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ "Ethel Mccully, Saved Virgin Islands Home from Condemnation". The New York Times. January 4, 1981. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

Ethel Walbridge McCully, the grandmother who went to Washington to "raise a little hell" on Capitol Hill in 1962, died Dec. 21 on St. John in the Virgin Islands in the home she successfully defended against condemnation by the National Park Service. She was 94 years old. Mrs. McCully was a secretary in New York City in 1947 when, on one of her frequent trips to the Caribbean, she first saw the island of St. John. She swam ashore with a basketful of belongings because the captain of her English cruise ship declined to dock at the then undeveloped island. Mrs. McCully, a small, outspoken woman, bought four acres, designed her dream house and spent 11 years struggling with suppliers, boat captains and workmen to build it. She described her tribulations in a book entitled Grandma Raised the Roof. Her home, called Island Fancy, was jeopardized in 1962 by a clause in a Congressional bill calling for the enlargement of the Virgin Islands National Park. The clause would have let the National Park Service acquire land on the island by condemnation. With other island homeowners, Mrs. McCully lobbied to get the provision struck from the bill. Some years ago, Mrs. McCully reluctantly sold the house to the Park Service with the proviso that she would have life tenancy.

- St. John Tradewinds—major Saint John newspaper, est. 1972

- Rankin, D.W. (2002). Geology of St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1631. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey.

- "36 Hours in St. John" (2006). The New York Times. Jon Rust

- "Why I Gave Up a $95,000 Job to Move to an Island and Scoop Ice Cream"—2015 Cosmopolitan article by Noelle Hancock

- Checklist: St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands - Stephanie Burt, Paste

- "House Hunting on ... St. John"—Marcelle S. Fischler, The New York Times