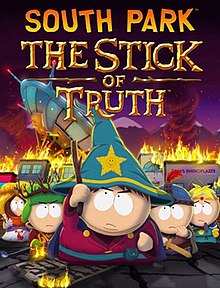

South Park: The Stick of Truth is a 2014 role-playing video game developed by Obsidian Entertainment in collaboration with South Park Digital Studios and published by Ubisoft. Based on the American animated television series South Park, the game follows the New Kid, who has moved to the eponymous town and becomes involved in an epic role-play fantasy war involving humans, wizards, and elves, who are fighting for control of the all-powerful Stick of Truth. Their game quickly escalates out of control, bringing them into conflict with aliens, Nazi zombies, and gnomes, threatening the entire town with destruction.

| South Park: The Stick of Truth | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | Obsidian Entertainment |

| Publisher(s) | Ubisoft |

| Director(s) |

|

| Producer(s) |

|

| Designer(s) | Matt MacLean |

| Programmer(s) | Dan Spitzley |

| Artist(s) | Brian Menze |

| Writer(s) |

|

| Composer(s) | Jamie Dunlap |

| Platform(s) | |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Role-playing |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

The game is played from a 2.5D, third-person perspective replicating the aesthetic of the television series. The New Kid is able to freely explore the town of South Park, interacting with characters and undertaking quests, and accessing new areas by progressing through the main story. By selecting one of four character archetypes, Fighter, Thief, Mage, or Jew, each offering specific abilities, the New Kid and a supporting party of characters use a variety of melee, ranged, and magical fart attacks to combat with their enemies.

Development began in 2009 after South Park creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone approached Obsidian about making a role-playing game designed to look exactly like the television series. Parker and Stone were involved throughout the game's production: they wrote its script, consulted on the design, and as in the television program, they voiced many of the characters. The Stick of Truth's production was turbulent; following the bankruptcy of the original publisher, THQ, the rights to the game were acquired by Ubisoft in early 2013, and its release date was postponed several times from its initial date in March 2013 to its eventual release in March 2014, for PlayStation 3, Windows, and Xbox 360.

The Stick of Truth was subject to censorship in some regions because of its content, which includes abortions and Nazi imagery; Parker and Stone replaced the scenes with detailed explanations of what occurs in each scene. The game was released to positive reviews, which praised the comedic script, visual style, and faithfulness to the source material. It received criticism for a lack of challenging combat and technical issues that slowed or impeded progress. A sequel, South Park: The Fractured but Whole, was released in October 2017, and The Stick of Truth was re-released in February 2018, for PlayStation 4 and Xbox One, and on Nintendo Switch in September 2018.

Gameplay

editSouth Park: The Stick of Truth is a role-playing video game[1] that is viewed from a 2.5D, third-person perspective.[2] The player controls the New Kid as he explores the fictional Colorado town of South Park.[3] The player can freely move around the town although some areas remain inaccessible until specific points in the story are reached. Notable characters from the series – including Cartman, Butters, Stan, and Kyle – join the New Kid's party and accompany him on his quests,[3] though only one character can be active at any time.[4] The game features a fast travel system, allowing the player to call on the character Timmy to quickly transport them to any other visited fast travel station.[5][6] At the beginning of the game, the player selects one of four character archetypes; the Fighter, Thief, Mage (which represent standard fantasy types), and the Jew. The Jew class specializes in "Jew-jitsu" and long-range attacks. Each class has specific abilities; armor and weapons are not limited by class, allowing a Mage to focus on melee attacks like a Fighter.[3][4]

The New Kid and his allies possess a variety of melee, ranged, and magic attacks.[7] Experience points rewarded for completing tasks and winning battles allow the New Kid to level up,[3] unlocking new abilities and upgrades such as increasing the number of enemies an attack hits or the amount of damage inflicted.[7] Magic is represented by the characters' ability to fart;[8] different farts are used to accomplish specific tasks. For example, the "Cup-A-Spell" allows the player to throw a fart to interact with a distant object,[9] the "Nagasaki" destroys blockades, and the "Sneaky Squeaker" can be thrown to create a sound that distracts enemies.[10] Attacks can be augmented with farts if the player has enough magical energy.[11]

The player has access to unlockable abilities that can open new paths of exploration, such as shrinking to access small areas like vents,[12] teleportation which allows the player to reach otherwise unreachable platforms, and farts which trigger an explosion that defeats nearby enemies when combined with a naked flame.[13] Actions committed against enemies outside of battle affects them in combat; the player or opponent who strikes first to trigger a fight will have the first turn in battle.[4][14] Combat takes place in a battle area separate from the open game world.[15] Battles use turn-based gameplay and each character takes a turn to attack or defend before yielding to the next character.[13]

During the player's turn, a radial wheel listing the available options—class-based basic melee attacks, special attacks, long-ranged attacks, and support items—appears.[16] Basic attacks are used to hit unarmored enemies and wear down shields; heavy attacks weaken armored enemies.[17] A flashing icon indicates that attacks or blocks can be enhanced to inflict more damage, or mitigate incoming attacks more effectively.[18] Each special attack costs a set amount of "Power Points" or "PP" (pronounced peepee) to activate.[3][19] Only one party member can join the player in battle.[4] Certain characters, such as Tuong Lu Kim,[20] Mr. Hankey,[21] Jesus, and Mr. Slave can be summoned during battle to deliver a powerful attack capable of defeating several enemies simultaneously; Jesus sprays damaging gunfire, while Mr. Slave squeezes an enemy into his rectum, scaring his allies away.[17]

One support item can be used each turn, including items that restore health or provide beneficial status effects that improve the character's abilities.[1] Weapons and armor can be enhanced using optional "strap-ons",[19] such as fake vampire teeth, bubble gum,[22] or a Jewpacabra claw.[19] These items can cause enemies to bleed and lose health,[22] weaken enemy armor, boost player health[19] or steal health from opponents, and disgust foes to make them "grossed out" and cause them to vomit.[15] Additionally, the "strap-ons" can set opponents on fire, electrocute them,[23] or freeze them.[20] Some enemies are immune to one or more of these effects.[20] Enemies can deflect certain attacks entirely; those in a riposte stance will deflect any melee attack, requiring the use of ranged weapons, while those in reflect stance will deflect ranged weapons.[1]

The player is encouraged to explore the wider game world to find Chinpokomon toys[22] or new friends who are added to the character's Facebook page.[13] Collecting friends allows the player to unlock perks that permanently improve the New Kid's statistics, providing extra damage or resistance to negative effects.[5][7] The character's Facebook page also serves as the game's main menu, containing the inventory and a quest journal.[3] The Stick of Truth features several mini-games, including defecating by repeatedly tapping a button that rewards the player with feces that can be thrown at enemies to trigger the "grossed out" effect, performing an abortion,[24] and using an anal probe.[25] Some of these scenes are absent from some versions of the game because of censorship.[25]

Synopsis

editSetting

editSouth Park: The Stick of Truth is set in the fictional town South Park in the Colorado Rocky Mountains.[26] The main character, whom the player controls, is the New Kid—nicknamed "Douchebag"[3]—a silent protagonist who has recently moved to the town.[21][27] Befriending the local boys, he becomes involved in an epic fantasy live action role-playing game featuring wizards and warriors battling for control of the Stick of Truth, a twig that possesses limitless power.[17][21]

The humans, led by Wizard King Cartman,[21] make their home in the Kingdom of Kupa Keep, a makeshift camp built in Cartman's backyard;[28] among their number are paladin Butters,[21] thief Craig,[1] Clyde,[29] cleric Token, Tweek, and Kenny—a young boy who dresses as a princess.[30] The humans' rivals are the drow elves,[21] who live in the elven kingdom in the backyard of their leader,[31] High Jew Elf Kyle;[32] they also include the warrior Stan and Jimmy the bard.[31] The boys conduct their game throughout the town,[18] the surrounding forest,[32] and even into Canada[33] (represented as a pixelated overhead 16-bit RPG).[23] Locations from the show, including South Park Elementary, South Park Mall, the Bijou Cinema, City Wok restaurant, and Tweek Bros. Coffeehouse, are featured in the game.[3]

The Stick of Truth features the following historical South Park characters: Stan's father Randy Marsh, school teacher Mr. Garrison, Jesus, school counsellor Mr. Mackey, former United States Vice-President Al Gore,[17] the sadomasochism-loving Mr. Slave,[34] sentient feces Mr. Hankey, City Wok restaurant owner Tuong Lu Kim,[29] Stan's uncle Jimbo,[35] Mayor McDaniels, Priest Maxi, Skeeter,[6] Canadian celebrities Terrance and Phillip,[36] the Underpants Gnomes,[7] the Goth kids, the Ginger kids,[32] the Crab People;[37] the Christmas Critters,[38] and local boys Timmy, Scott Malkinson, and Kevin Stoley.[1]

Plot

editThe New Kid has moved with his parents to South Park to escape his forgotten past. He quickly allies with Butters, Princess Kenny and their leader Cartman. Nicknamed "Douchebag", the New Kid is introduced to the coveted Stick of Truth. Shortly thereafter, the elves attack Kupa Keep and take the Stick. Cartman banishes Clyde from the group for failing to defend the Stick from the elves. With the help of Cartman's best warriors, Douchebag recovers the Stick from Jimmy. That night, Douchebag and several town residents are abducted by aliens. Douchebag escapes his confinement with the help of Stan's father, Randy, and crashes the alien ship into the town's mall.

By morning, the UFO crash site has been sealed off by the US government, who has put out a cover-story that claims a Taco Bell is being built. Douchebag visits Kupa Keep and learns that the Stick has again been stolen by the elves. Cartman and Kyle task Douchebag with recruiting the Goth kids for their respective sides, each claiming that the other has the Stick. Randy agrees to help Douchebag recruit the Goths after Douchebag infiltrates the crash site and discovers that government agents are plotting to blow up the town in order to destroy an alien goo released from the ship. The goo turns living creatures into Adolf Hitler-esque Nazi Zombies; an infected person escapes government containment, unleashing the virus on South Park.

That night, Cartman or Kyle (dependent on which character the player chooses to follow) leads his side against the other at the school. Here, the children learn that Clyde stole the Stick as revenge for his banishment. Clyde rallies defectors from the humans and elves, and uses the alien goo to create an army of Nazi Zombies. The humans and elves join together to oppose Clyde but there are too few to fight him. Later, Gnomes steal Douchebag's underpants; after defeating them, Douchebag gains the ability to change size at will.

Out of desperation, Douchebag is told to invite the girls to play. They agree to join after Douchebag infiltrates an abortion clinic and travels across Canada to discover which of their friends is spreading gossip. Flanked by the girls, kindergarten pirates, and Star Trek role-players, the humans and elves attack Clyde's dark tower. Randy arrives and reveals that the government agents have planted a nuclear device in Mr. Slave's anus to blow up South Park, forcing Douchebag to shrink and enter Mr. Slave to disarm the bomb.[4] After exiting Mr. Slave, Douchebag finally confronts Clyde and is forced to fight a resurrected Nazi Zombie Chef; Chef is defeated. Clyde decides he is not playing any more and Cartman kicks him from the tower.

The government agents arrive, revealing that Douchebag went into hiding to escape them because of his ability to quickly make friends on social networks such as Facebook, which the government wanted to use for its own ends. Learning of the Stick's supposed power, the chief agent takes it and bargains with Douchebag to help him use it. Douchebag refuses but Princess Kenny betrays the group, uses the Stick to fight them and infects himself with the Nazi Zombie virus. Unable to defeat Nazi Zombie Princess Kenny, Cartman tells Douchebag to break their sacred rule by farting on Kenny's balls, which he does. The resulting explosion defeats Kenny and cures the town of the Nazi Zombie virus. In the epilogue as South Park is rebuilt, the group retrieves the Stick of Truth; they decide its power is too great for any person to hold and throw it into Stark's Pond.[39]

Development

editDevelopment of South Park: The Stick of Truth took four years, beginning in 2009 when South Park co-creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone contacted Obsidian Entertainment to discuss their desire to make a South Park game. Parker, a fan of Obsidian games, including Fallout: New Vegas (2010), wanted to create a role-playing game, a genre which he and Stone had enjoyed since their childhoods.[40][41][42] Parker and Stone insisted that the game must replicate the show's visual style.[40] Parker's original concept was for a South Park version of the 2011 role-playing fantasy game The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, and he estimated the first script he produced to be 500 pages long.[41] The South Park Digital Studios team animated a concept of the game's opening scene to show what they wanted to accomplish with Obsidian in terms of appearance and gameplay mechanics.[43] While the series had inspired several licensed games, such as South Park (1998) and South Park Rally (2000), Parker and Stone were not involved in these games' development and later criticized the titles' quality. Negative reaction to those games made the pair protective of their property and led to their greater involvement on The Stick of Truth; they refused several requests to license the series for new ventures.[41]

Stone and Parker worked closely with Obsidian on the project, sometimes having two-to-three-hour meetings over four consecutive days. They worked with Obsidian until two weeks before the game was shipped.[40] Their involvement extended beyond creative input; their company initially financed the game, believing that a game based on the controversial television show would struggle to receive financial support from publishers without them placing restrictions on the content to make it more marketable. The initial funding was intended to allow Obsidian to develop enough of the game to show a more complete concept to potential publishers.[40] In December 2011, THQ announced that they would work with Obsidian on South Park: The Game, as it was then known.[44] This partnership developed into a publishing arrangement after South Park owner Viacom, having grown wary of video games, cut its funding. Obsidian was aware when it signed with THQ that the latter was experiencing financial difficulties.[40]

In March 2012, Microsoft canceled Obsidian's upcoming Xbox One project codenamed "North Carolina" after seven months of development, resulting in the layoff of between 20 and 30 employees, including members of the Stick of Truth team.[45][46] In May 2012, the game's final title was announced.[47] In December 2012, THQ filed for chapter 11 bankruptcy after suffering several product release failures. The Stick of Truth remained on schedule as THQ tried to use the bankruptcy period to restructure and return its business to profit, but the company failed to find a buyer and a Delaware court ordered that THQ was worth more if its assets were sold individually.[48][49]

The rights to The Stick of Truth were auctioned in late December 2012; Obsidian was not made aware of the sale until the auction was announced.[40][50] South Park Digital Studios filed an objection to the auction, stating that THQ did not have the authority to sell the publishing rights and that THQ had been granted exclusive use of specific South Park trademarks and copyrights. South Park Digital also argued that even if the rights were sold, THQ would still owe them US$2.27 million and that they held the option of reclaiming all elements of the game and South Park related creations. THQ requested that the court overrule South Park Digital, stating that their rights were exclusive and thus transferable. On January 24, 2013, the United States bankruptcy court approved the sale of THQ's assets, including The Stick of Truth.[51][52]

The rights were bought by Ubisoft for US$3.2 million. Within three weeks they had decided that the game required significant changes, pushing its release date back by six months to March 2014. Parker and Stone, with input from a Ubisoft creative consultant, concluded that their original vision would take too long and would be too costly to produce.[41] In a 2014 interview, Obsidian leader Feargus Urquhart said he could not comment on changes that were made following Ubisoft's involvement.[40][50] South Park: The Stick of Truth was officially released to manufacturing on February 12, 2014.[53] Following its release, Stone said that the work involved in making the game was much more than he and Parker had anticipated. He said, "I'll [admit] to the fact that we retooled stuff that we didn't like and we worked on the game longer than other people would've liked us to".[54]

Design

editI haven't played it [EarthBound] again in forever, but I just remember something being about "Oh wow, I'm a little kid in a house and there's my mom and I go outside my house and am fighting like an ant and a little mouse." It started out feeling so real,... I kept having in my head "do I really want [South Park: The Stick of Truth] to feel like that you are a little kid and you're playing this game and bigger shit ends up happening."

During early discussions with Obsidian, Parker and Stone were adamant that the game should faithfully replicate the show's unique 2D-style visuals, which are based on cutout animation. Obsidian provided proofs of concept that they could achieve the South Park look; Stone and Parker were satisfied with this.[56] The show is animated using Autodesk Maya, but Obsidian produced the game assets and animations in Adobe Flash.[57] Skyrim was the game's initial influence and further inspiration came from the 1995 role-playing game EarthBound.[41] Parker and Stone said that the blended 2D/3D visuals of Paper Mario and the silent protagonist Link from The Legend of Zelda series also provided inspiration for the design.[55] The characters' costumes and classes are taken from the 2002 South Park episode "The Return of the Fellowship of the Ring to the Two Towers".[58] Obsidian created various fantasy-styled items, armor, and weapons but Parker and Stone told them to "make it crappier" to create the impression that the children had found or made the objects themselves; weapons consisted of golf clubs, hammers, suction cup arrows and wooden swords, while bathrobes, oven mitt gloves, and towels worn as capes served as clothing. South Park studios provided Obsidian with access to the show's full archive of art assets, allowing Obsidian to include previously unused ideas, such as discarded Chinpokomon designs.[59] Actors from the show provided voice work, and Obsidian was given access to South Park's audio resources, including sound effects, music, and the show's composer Jamie Dunlap.[60][61]

Describing the writing of a comedy script for a game in which lines of dialog may be heard repeatedly and jokes could appear dated, Stone said:

We write jokes, and the jokes are funny. With a game, the fourth, fifth, sixth, 80th, 100 millionth time you've seen that joke it becomes not funny, then you lose faith in it, and then you question it, and you go round this emotional circle ... We've always liked fresh-baked stuff a little better but, with a video game, it doesn't work that way. But the game isn't just a collection of funny South Park scenes, hopefully it's more than that.[62]

Like the show, The Stick of Truth satirizes political and social issues including abortion, race relations, anal probes, drug addiction, sex, extreme violence, and poverty. Creative consultant Jordan Thomas said, "The way we looked at [humor] was if this moment was a hot button for the audience, should we make it worse, because [Stone and Parker] love to push boundaries and their default response was definitely not to back down, but the really healthy counterbalance was, can we make it funnier—and the answer was often yes".[3]

The game underwent several changes during its development. While the final game features four playable character types (Fighter, Thief, Mage, and Jew), an early version featured five playable classes: Paladin, Wizard, Rogue, Adventurer, and Jew. The latter was described as a cross between a Monk and a Paladin, that is "high risk, high reward" and strongest when closest to death.[63] The game had included other enemies and locations, including vampire children who were fought in a cemetery and church, hippies, a mission to recover Cartman's doll from the Ginger children, and boss fights against a large, winged monster,[37][64] and celebrity Paris Hilton—her main attack being called the "vag blast".[65] The Crab People had a larger role and shared a demilitarized zone with the Underpants Gnomes—only one Crab Person appears in the final game—and Mr. Hankey and his family lived in a large, Christmas-themed village which became a small house in the town's sewers.[37] Urquhart later said that when development began, video games were less protected by freedom of speech laws than other media, restricting the content that could be included in The Stick of Truth.[65] While under THQ's publishing deal, the developers planned that the Xbox 360 version would support the console's input device, Kinect, enabling players to give characters voice commands, taunt enemies, and insult Cartman—to which the character would respond. Exclusive Xbox 360 downloadable content (DLC) including the Mysterion Superhero pack and Good Times with Weapons packs each featuring a unique weapon, outfit, and special attack, and three story-based campaign expansions was announced. These features were not present in the Ubisoft release.[66][67]

Release

editSouth Park: The Stick of Truth was released in North America on March 4, 2014, for the PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360 consoles, and Windows. It was released on March 6 in Australia and on March 7 in Europe.[68] The game had been scheduled for release on March 5, 2013, but this was postponed two months by then-publisher THQ.[69] After THQ filed for bankruptcy in January 2013, Ubisoft purchased the rights to publish the game and did not specify a release date.[70] By May 2013, Ubisoft had confirmed that it would be released that year after it was omitted from their upcoming games release schedule.[71] On September 26, 2013, Ubisoft announced that The Stick of Truth would be released in December 2013,[72] but in October 2013 the game's release was again postponed until March 2014.[73] The game was scheduled for release on March 6, 2014 in Germany and Austria, but it was delayed after the localized version of the game was found to contain Nazi references.[74] Alongside the Steam version of the game, The Stick of Truth received a digital download release for PlayStation 4 and Xbox One on June 13, 2016. The console versions were only available as a free pre-order incentive to customers who pre-ordered its sequel, The Fractured but Whole.[75] A stand-alone physical and digital download was released on for February 13, 2018, for PlayStation 4 and Xbox One.[76] A Nintendo Switch version, available as a digital download, was released on September 25, 2018.[77][78]

A collector's edition called the "Grand Wizard Edition" containing the game, a 6-inch figure of Grand Wizard Cartman created by Kidrobot, a map of the South Park kingdom, and the Ultimate Fellowship DLC was made available. The Ultimate Fellowship content includes four outfits with different abilities; the Necromancer Sorcerer outfit provides increased fire damage, the Rogue Assassin outfit rewards the player with extra money, the Ranger Elf outfit raises weapon damage, and the Holy Defender outfit increases defense.[79] Additional content included the Super Samurai Spaceman pack containing three outfits; the Superhero costume provides a buff at the start of battle, the Samurai costume provides a buff on defeating an enemy, and the Spaceman costume provides a defensive shield.[80]

In November and December 2013, the South Park television series featured the "Black Friday" trilogy of episodes—"Black Friday", "A Song of Ass and Fire", and "Titties and Dragons"—which was a narrative prequel to the game and featured the characters wearing outfits and acting out roles similar to those in the game.[81][82][83] The episodes satirized the game's lengthy development; in "Black Friday" Cartman tells Kyle not to "pre-order a game that some assholes in California haven’t even finished making yet", referring to California-based Obsidian,[84] while "Titties and Dragons" concludes with an advertisement announcing the game's release date accompanied by Butters declaring his skepticism.[85] Discussing "Black Friday", IGN said that it "felt like a sneak peek" and provided some marketing for Stick of Truth.[86]

Censorship

editShortly before the game's release, Ubisoft announced that it would voluntarily censor seven scenes, calling it a "market decision made by Ubisoft EMEA" localizers and not a response to input from censors.[87][88] PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360 versions were affected in European territories, the Middle East, Africa, and Russia, while the Windows version remained uncensored.[89] The censorship affected all formats in Australia, Singapore, Hong Kong, Germany, Austria, and Taiwan.[90] The North American release was the only version that was uncensored on all formats. The German version was specifically censored because of the use of Nazi and Hitler-related imagery, including swastikas and Nazi salutes, which are illegal in that country. A spokesman for the European video game content rating system Pan European Game Information (PEGI) confirmed that the uncensored version had been submitted and approved for release with an 18 rating, meaning the game would be acceptable for people over eighteen years of age. Ubisoft resubmitted the censored version without input from PEGI; this version was passed with an 18-rating.[89]

The scenes Ubisoft removed depict anal probing by aliens and the player-character performing an abortion. In their place, the game displays a still image of a statue holding its face in its hand, with an explicit description of events depicted in the scene.[89] In Australia, the same scenes were removed because the Australian Classification Board refused to rate the game for release due to the depiction of sexual violence—specifically the child player-character being subjected to anal probing and the interactive abortion scene. Like the European version, these scenes were replaced with a placeholder card with an explanation of what was removed on a background image of a koala crying.[91]

Discussing the situation, Stone said he had been told changes were required for the game to be released and that he and Parker inserted the placeholder images so the censorship would not be hidden. He called the censorship a double standard that the pair resisted, and said he felt it did not ruin the game and the cards allowed them to mock the changes.[92] A post-release user-created game modification was released for the Windows version that disabled the censorship.[93]

Reception

editCritical response

edit| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| Metacritic | PC: 85/100[94] PS3: 85/100[95] X360: 82/100[96] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| Computer and Video Games | 9/10[97] |

| Destructoid | 8/10[5] |

| Edge | 8/10[98] |

| Electronic Gaming Monthly | 8.5/10[10] |

| Game Informer | 8.5/10[99] |

| GameSpot | 7/10[19] |

| GameZone | 8/10[100] |

| Giant Bomb | [23] |

| IGN | 9/10[4] |

| PSU | 8/10[101] |

South Park: The Stick of Truth received positive reviews from critics.[89] Aggregating review website Metacritic provides a score of 85 out of 100 from 48 critics for the Windows version,[94] 85 out of 100 from 31 critics for the PlayStation 3 version,[95] and 82 out of 100 from 33 critics for the Xbox 360 version.[96]

The game was considered a successful adaptation of licensed material to a video game, with critics describing it as one of the most faithful video game adaptations ever, such that moving the player-character was like walking on the set of the show.[7][18][22][97] GamesRadar+ said that The Stick of Truth was to South Park as Batman: Arkham Asylum was to the Batman franchise in terms of reverence to the source material while breaking new ground in video games. They praised the "open-world South Park to explore, with a solid 12–14 hours of inside jokes, obscure references, and humor that pulls from 17 TV seasons' worth of social commentary and offensive humor."[18][20] Computer and Video Games said that the game contained so many references to the show's history that it made Batman: Arkham City appear sparse.[4][97] Destructoid said that the ability to walk around the detailed town provided a sense of wonderment similar to exploring The Simpsons's home town in Virtual Springfield.[5] The visual translation was highlighted as a significant component of the game's success, appearing indistinguishable from an episode of the show and providing a consistent aesthetic that remained faithful to the series while being original to gaming.[4][19][22] Some reviewers said that the art style was occasionally detrimental, obscuring objects and prompts, and that repetitive use of animations grew stale over the course of the game.[97] Computer and Video Games said that Obsidian had built a game world that seemed as though it had always existed.[97]

Reviewers consistently highlighted its comedic achievement.[4][98] Game Informer said it is frequently hilarious, ranking it among the best comedic games ever released.[7] IGN praised The Stick of Truth for its witty and intelligent satire of the role-playing genre, while others said that as well as being consistently funny, the game was suitably boisterous, shocking, provocative, self-effacing, and fearless in its desire to offend.[4][98] Many reviewers agreed that much of the content was more appealing to South Park fans; some jokes are lost on the uninitiated but others said that enough context was provided for most jokes to be funny regardless of players' familiarity with the source material.[17][18][22] IGN said that it is the game South Park fans have always wanted,[4] but some reviewers said that without the South Park license, the game's shallowness would be more obvious.[19]

Combat received a polarized response; critics alternately called the battles deep and satisfying or shallow and repetitive. Reviewers considered the combat mechanics to be simplistic while allowing for complex tactics, and others said that the requirement to actively defend against enemy attacks and enhance offense kept fights engaging.[4][18] Others also praised the combat but considered the mechanics to be robust and elaborate, presenting a solid role-playing combat system concealed under the intentionally simplistic visuals.[22][97] Some reviewers said that a lack of depth made combat gradually become repetitive;[17][22][97] they said that even when combat is funny and engaging, by the end of the game the battles can become routine.[17][18] Joystiq stated that defense was more interesting than offense because it relied on time-sensitive reactions to creative enemy attacks such as Al Gore giving a presentation.[17] Destructoid said there are too few powers available for offense for the game to remain interesting for long.[5] GameSpot found combat was too easy and lacking in challenge because of an abundance of supplement items such as health packs that were found more frequently than they were used, and powerful abilities that quickly subdued opponents.[19][98] Others disagreed, stating that the variety offered in combat, such as character abilities, allies, weapons, armor, and upgrades, ensured it always felt fun.[97][98] The effects of the enhancements were sometimes considered to be confusing,[18] and typically relying on simply equipping the highest level item available.[19] Joystiq said the special characters that can be summoned during battle were extreme in terms of power and entertainment value.[17]

IGN said that the difference between character classes such as Thief and Jew were disappointingly minimal, offering little variety or incentive to replay as another class.[4] IGN also said some missions and side quests were tedious, and were elevated by their setting rather than their quality,[5] while the reviewer thought the environmental puzzles were a clever option for avoiding combat and were rare enough to be enjoyable when available. However, GameSpot said the puzzles felt scripted and simple.[19][97] Reviewers said that many of the gameplay functions and controls were poorly explained, making them difficult to activate; others were critical of excessive loading times upon entering new locations and slow menus such as the Facebook panel.[4][18][98]

Sales

editDuring the first week of sales in the United Kingdom, South Park: The Stick of Truth became the best-selling game on all available formats (In terms of boxed sales), replacing Thief. The Xbox 360 version accounted for 53% of sales, followed by the PlayStation 3 (41%), and Windows (6%).[102] In its second week, sales fell 47% and the game dropped to third place behind Titanfall and Dark Souls II.[103] South Park: The Stick of Truth was the top-selling game on the digital-distribution platform Steam between March 2 and 15, 2014.[104][105] It was the third best-selling game of March 2014, behind Titanfall and Thief,[106] and the thirty-first best-selling physical game of 2014.[107]

In North America, South Park: The Stick of Truth was the third best-selling physical game of March 2014, behind Titanfall and Infamous Second Son.[108] Digital distribution accounted for 25% of the game's sales, making it Ubisoft's most downloaded title at the time.[109] It was the ninth best-selling downloadable game of 2014 on the PlayStation Store.[110] In May 2015, Ubisoft confirmed that the game had sold 1.6 million copies as of March 2015.[111] As of February 2016, Ubisoft had shipped 5 million copies of the game.[112]

Accolades

editAt the 2012 Game Critics Awards, The Stick of Truth was named the '"Best Role-Playing Game".[113] At the 2014 National Academy of Video Game Trade Reviewers (NAVGTR) awards the game received awards for "Writing in a Comedy", "Animation" in the artistic category, and best "Non-Original Role Playing Game". It also received nominations for "Game of the Year", "Original Light Mix Score (Franchise)" and "Sound Effects". Parker's multi-character voice work won him the award for "Performance in a Comedy, Supporting"; Stone was also nominated.[114] At the 2014 Golden Joystick Awards, The Stick of Truth received three nominations for "Game of the Year", "Best Storytelling", and "Best Visual Design".[115] At the inaugural Game Awards event, Trey Parker won for "Best Performance" for his multiple roles, and the game received two nominations for "Best Role-Playing Game" and "Best Narrative".[116][117] At the 2015 South by Southwest festival, the game received the "Excellence in Convergence" award for achievements in adapting material from another entertainment medium.[118] During the 18th Annual D.I.C.E. Awards, The Stick of Truth received a nomination for "Outstanding Achievement in Story".[119]

IGN listed it as the 50th-best game of the contemporary console generation,[120] and Giant Bomb named it the Best Surprise of 2014 for overcoming its development issues.[121] Shacknews and Financial Post labeled it the seventh-best game of 2014, while The Guardian named it as the 12th-best.[122][123][124] Kotaku listed Dunlap's score as one of the best of the year, saying that it was "a really good tongue-in-cheek Skyrim knockoff that captured South Park's bright musicality."[125] In 2017, IGN listed the pixelated Canada area at number 98, on its list of the Top 100 Unforgettable Video Game Moments,[126] and PC Gamer named it one of the best role playing games of all time.[127] In 2018, Game Informer labeled it the 82nd-best RPG of all time, stating "in the world of licensed video games, few titles stand out as exceptional or worthy of the source material."[128]

Sequel

editIn March 2014, Stone said that he and Parker were open to making a sequel, depending on the reception for The Stick of Truth.[54] A sequel, South Park: The Fractured but Whole, was announced in June 2015. The game was developed by Ubisoft San Francisco, replacing Obsidian Entertainment, for PlayStation 4, Windows, and Xbox One.[129][130] The sequel was released worldwide on October 17, 2017 to generally positive reviews. In it, the player again controls the New Kid, joining the children of South Park as they role-play superheroes.[131][132] A Nintendo Switch version, adapted by Ubisoft Pune, was released in 2018.[133][134]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e Hannley, Steve (March 4, 2014). "Review: South Park: The Stick of Truth". Hardcore Gamer. Archived from the original on March 6, 2014. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ^ Walker, John (March 6, 2014). "Review – South Park: Stick of Truth". Metro Weekly. Archived from the original on April 13, 2014. Retrieved April 13, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Filari, Alessandro (February 14, 2014). "Preview: South Park: The Stick of Truth is ambitious". Destructoid. Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n McCaffrey, Ryan (March 3, 2014). "South Park: The Stick of Truth Review". IGN. Archived from the original on November 30, 2014. Retrieved March 26, 2014. ( Page will play audio when loaded)

- ^ a b c d e f Carter, Chris (March 4, 2014). "South Park: The Stick of Truth". Destructoid. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ^ a b Lewis, Anne (February 19, 2014). "South Park: The Stick Of Truth – New Kid, Old Friends". Ubiblog. Ubisoft. Archived from the original on February 6, 2016. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Ryckert, Dan (March 4, 2014). "South Park: The Stick of Truth". Game Informer. Archived from the original on March 26, 2014. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ^ Reeves, Ben (August 22, 2013). "Ubisoft Has The Funniest Game At Gamescom". Game Informer. Archived from the original on October 8, 2013. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ McElroy, Justin (June 4, 2014). "South Park: The Stick of Truth summons the magic of farts". Polygon. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved January 23, 2016.

- ^ a b Carsillo, Ray (March 4, 2014). "EGM Review: South Park: The Stick of Truth". Electronic Gaming Monthly. Archived from the original on March 30, 2014. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ Walker, John (March 4, 2014). "Wot I Think – South Park: The Stick Of Truth". Rock, Paper, Shotgun. Archived from the original on March 30, 2014. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ McLaughlin, Rus (June 4, 2013). "In South Park: The Stick of Truth, farting is magic (preview)". VentureBeat. Archived from the original on February 5, 2016. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

- ^ a b c Reyes, Francesca (March 4, 2014). "South Park: The Stick of Truth review". Official Xbox Magazine. Archived from the original on March 6, 2014. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ^ Futter, Mike (October 11, 2013). "South Park: The Stick Of Truth Looks Like Mario RPG With Bodily Functions". Game Informer. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ a b Turi, Tim (June 4, 2013). "LARPing And Projectile Poop In South Park: The Stick Of Truth". Game Informer. Archived from the original on November 15, 2013. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ Reseigh-Lincoln, Dom (February 14, 2014). "South Park: The Stick Of Truth gameplay preview – A Song Of Ass And Fire". PlayStation Official Magazine. Archived from the original on June 9, 2014. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Prell, S (March 4, 2014). "South Park: The Stick of Truth review: Come on down". Joystiq. Archived from the original on March 9, 2014. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Cooper, Hollander (March 4, 2014). "South Park: The Stick Of Truth Review". GamesRadar. Archived from the original on March 21, 2014. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Van Ord, Kevin (March 4, 2014). "South Park: The Stick of Truth Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on March 12, 2014. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Sterling, Jim (March 4, 2014). "South Park: The Stick of Truth Review – A Storm of Swear Words". The Escapist. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Cook, Dave (March 4, 2014). "South Park: The Stick of Truth is the funniest episode in years". VG247. Archived from the original on September 9, 2015. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h McElroy, Justin (March 4, 2014). "South Park: The Stick Of Truth Review: Pen And Paper". Polygon. Archived from the original on March 21, 2014. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ^ a b c Navarro, Alex (March 4, 2014). "South Park: The Stick of Truth Review". Giant Bomb. Archived from the original on March 7, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ Welch, Haanu (March 31, 2014). "10 of the Most Delightfully Disturbing Things We Did in "South Park: The Stick of Truth"". Complex. Archived from the original on April 3, 2014. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- ^ a b Savage, Phil (February 27, 2014). "South Park: The Stick of Truth's PC version will only be censored in certain territories". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on March 5, 2014. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- ^ Griffiths, Eric (June 21, 2007). "Young offenders". New Statesman. Archived from the original on February 6, 2013. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- ^ Cook, Dave (March 4, 2014). "South Park: The Stick of Truth is the funniest episode in years (Page 2)". VG247. Archived from the original on October 3, 2015. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ^ Williamson, Steven (March 4, 2014). "South Park: The Stick of Truth Review – a side-splitting RPG with real character (Page 2)". PlayStation Universe. Archived from the original on March 28, 2016. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- ^ a b Brown, Billy; Ballard, Jason (April 16, 2015). "Gamer Buzz: South Park Meets Santa's Little Helper". Paste. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved December 18, 2015.

- ^ Martin, Liam (March 4, 2014). "South Park: The Stick of Truth review (360) Captures the show's humour". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on April 4, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ^ a b Lewis, Anne (March 5, 2014). "The Beginner's Guide To South Park: The Stick Of Truth". Ubiblog. Ubisoft. Archived from the original on January 11, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ^ a b c Cooper, Lee (March 10, 2014). "South Park: The Stick of Truth Trophy Guide". Hardcore Gamer. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ Schreier, Jason (April 3, 2014). "South Park: The Stick of Truth: The Kotaku Review". Kotaku. Archived from the original on February 2, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ^ Lanxon, Nate (March 10, 2014). "South Park: The Stick of Truth Review (Xbox 360, PS3, PC)". Wired. Archived from the original on March 28, 2014. Retrieved April 13, 2014.

- ^ Wilson, Iain. "South Park: The Stick of Truth side quests guide". GamesRadar. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved December 18, 2015.

- ^ Welch, Haanu (March 31, 2014). "10 of the Most Delightfully Disturbing Things We Did in "South Park: The Stick of Truth"". Complex. Archived from the original on April 3, 2014. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- ^ a b c Ryckert, Dan (March 27, 2014). "The Deleted Content Of South Park: The Stick Of Truth". Game Informer. Archived from the original on April 3, 2014. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- ^ McCaffrey, Ryan (March 4, 2014). "South Park: The Stick Of Truth Review: Meet Some Friends Of Mine". IGN. Archived from the original on March 9, 2014. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- ^ Obsidian Entertainment (March 4, 2014). South Park: The Stick of Truth. Ubisoft. Scene: Ending.

Kyle: You guys sure about this? / Cartman: There's no other way. / Stan: It drove our friend to madness and nearly killed us all. / [Cartman throws the stick into the pond, where it sinks] / Cartman: So what do you guys wanna play now? / Stan: How about dinosaur hunters?! / Kyle: Or pharaohs and mummies! / Cartman: Let's ask Douchebag! What do you wanna play next, dude? / The New Kid: Screw you guys. I'm going home. / Cartman: Wow. what a dick.

- ^ a b c d e f g Yin-Poole, Wesley (March 12, 2014). "South Park: It all started with a suspected prank call". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Kepler, Adam W. (March 3, 2014). "Finally, Cartman Can Come Out to Play". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 23, 2014. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ^ Caoili, Eric (December 1, 2011). "Fallout: New Vegas Developer Working On South Park RPG". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on January 3, 2012. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- ^ Fletcher, JC (October 10, 2012). "Obsidian's Avellone on South Park and the continued appeal of external franchises". Joystiq. Archived from the original on July 15, 2013. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ "THQ Joins Forces with South Park Digital" (Press release). THQ. December 1, 2011. Archived from the original on October 24, 2013. Retrieved December 2, 2011.

- ^ Sliwinski, Alexander (March 14, 2012). "Report: Obsidian hit with layoffs; South Park team affected, future next-gen title canceled". Joystiq. Archived from the original on June 16, 2013. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ Schreier, Jason (March 14, 2012). "Rumor: Obsidian's Cancelled Project Was For The Next Xbox, Published By Microsoft". Kotaku. Archived from the original on March 30, 2014. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ Hilliard, Kyle (May 5, 2012). "Rumor: Obsidian's South Park RPG Has A New Name". Game Informer. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ Matulef, Jeffrey (December 19, 2012). "THQ files for bankruptcy". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on July 25, 2013. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ^ "'South Park: The Stick of Truth' Release Date Delayed; Game Pushed To Later In 2013 by Ubisoft". International Digital Times. March 4, 2013. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- ^ a b Matulef, Jeffrey (January 24, 2013). "THQ is no more. This is where its assets went". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on August 30, 2013. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ^ Conditt, Jessica (January 22, 2013). "South Park Studios battles THQ over potential sale of The Stick of Truth". Joystiq. Archived from the original on July 15, 2013. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ Fletcher, JC (March 14, 2012). "Court approves THQ asset sales". Joystiq. Archived from the original on June 9, 2013. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- ^ Pereira, Chris (February 12, 2014). "South Park: The Stick of Truth Goes Gold". IGN. Archived from the original on March 12, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ a b McCaffrey, Ryan (March 17, 2014). "South Park Co-Creator on Stick of Truth Sequel Potential". IGN. Archived from the original on April 2, 2014. Retrieved April 2, 2014.

- ^ a b Ruscher, Wesley (July 19, 2013). "South Park: The Stick of Truth inspired by EarthBound". Destructoid. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ^ Video interview with Obsidian Entertainment CEO Feargus Urquhart. In: Hanson, Ben (December 5, 2011). "Crafting The South Park RPG". Game Informer. Archived from the original on May 9, 2013. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- ^ Reeves, Ben (October 21, 2016). "Don't Forget To Bring A Buddy – A Look At South Park: Fractured But Whole's Allies". Game Informer. Archived from the original on November 21, 2017. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- ^ Millian, Mark (December 1, 2011). "'South Park' console game to debut next year". CNN. Archived from the original on June 18, 2012. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- ^ Vore, Bryan (December 21, 2011). "What You'll Find In South Park". Game Informer. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ Hanson, Ben (December 19, 2011). "Capturing The Sounds Of South Park". Game Informer. Archived from the original on April 16, 2012. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ Abramson, Seth (March 14, 2014). "Metamericana: South Park: The Stick Of Truth Is A Fantasy Rpg That'S All Too Real". Indiewire. Archived from the original on March 15, 2014. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- ^ Day, James (March 7, 2014). "South Park's Matt Stone: European censors cut abortion and anal probe scenes from our Stick Of Truth game". Metro. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014. Retrieved April 2, 2014.

- ^ Hinkle, David (December 14, 2011). "South Park's fifth character class is the 'Jew'". Joystiq. Archived from the original on July 21, 2013. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ Ryckert, Dan (March 27, 2014). "The Deleted Content Of South Park: The Stick Of Truth". Game Informer. Archived from the original on April 3, 2014. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- ^ a b Osborn, Alex (February 1, 2017). "Paris Hilton Was Almost A Boss In South Park: The Stick Of Truth – Ign Unfiltered". IGN. Archived from the original on February 1, 2017. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ^ Jackson, Mike (June 4, 2012). "South Park: The Stick of Truth release date, DLC, trailer". Computer and Video Games. Archived from the original on June 6, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ^ Sliwinski, Alexander (June 4, 2012). "South Park: The Stick of Truth is coming March 5, no lie (Update: Kinect integration, DLC first on Xbox Live)". Joystiq. Archived from the original on March 13, 2014. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ Scullion, Chris (February 25, 2014). "South Park: The Stick Of Truth 'censored in Europe and Australia'". Computer and Video Games. Archived from the original on March 5, 2014. Retrieved April 4, 2014.

- ^ Reilly, Jim (November 5, 2012). "South Park: The Stick Of Truth Delayed Again". Game Informer. Archived from the original on September 11, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ^ Crossley, Rob (January 25, 2013). "Ubisoft confirms capture of THQ Montreal game, sets South Park for '2013'". Computer and Video Games. Archived from the original on March 13, 2014. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- ^ Gera, Emily (May 3, 2013). "South Park: The Stick of Truth is still on track for 2013 launch, Ubisoft confirms". Polygon. Archived from the original on September 11, 2013. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- ^ Fahmy, Albaraa (September 26, 2013). "'South Park: The Stick of Truth' release date revealed". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- ^ Miller, Greg (October 31, 2013). "South Park: The Stick of Truth Delayed". IGN. Archived from the original on December 6, 2013. Retrieved April 4, 2014.

- ^ Tach, Dave (March 5, 2014). "Why South Park: The Stick of Truth was delayed in Austria and Germany". Polygon. Archived from the original on April 6, 2014. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- ^ Dornbush, Jonathon (June 13, 2016). "E3 2016: South Park: The Stick Of Truth Coming To Ps4, Xbox One". IGN. Archived from the original on June 13, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ^ Makedonski, Brett (January 25, 2018). "South Park: The Stick of Truth set to come to PS4 and Xbox One next month". Destructoid. Archived from the original on January 27, 2018. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- ^ Kent, Emma (July 18, 2018). "South Park: The Stick of Truth headed to Nintendo Switch, months after its sequel". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on August 27, 2018. Retrieved August 27, 2018.

- ^ Bankhurst, Adam (September 17, 2018). "South Park: The Stick Of Truth Coming To Switch". IGN. Archived from the original on September 17, 2018. Retrieved September 7, 2018.

- ^ Goldfarb, Andrew (September 25, 2013). "South Park: Stick of Truth Release Date, Special Edition Revealed". IGN. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ Karmali, Luke (October 17, 2013). "South Park: The Stick of Truth Pre-Order Bonuses". IGN. Archived from the original on December 6, 2013. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ^ Futter, Mike (March 10, 2014). "Opinion – Three Reasons Why The Stick Of Truth Succeeds". Game Informer. Archived from the original on March 30, 2014. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ Trinh, Mike (November 14, 2013). "Latest South Park Episode Tackles Console WarSucceeds". Game Informer. Archived from the original on March 30, 2014. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ Keiser, Joe (March 4, 2014). "South Park's mix of smut and smarts is in full force in The Stick Of Truth". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on March 30, 2014. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ Longo, Chris (November 11, 2013). "South Park: Black Friday, Review". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on March 30, 2014. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ Parker, Trey (Director), Parker, Trey (Writer) (December 4, 2013). Titties and Dragons (Television show). South Park. United States: Comedy Central.

Cartman: The last few weeks we've been too busy to play video games. And look at what we did. There's been drama, action, romance. I mean honestly you guys, do we need video games to play? Maybe we started to rely on Microsoft and Sony so much that we forgot that all we need to play are the simplest things. Like, like this [Picks up a twig] we can just play with this. Screw video games dude, who fucking needs them. Fuck 'em. [Cartman holds the stick high as an image of the Stick of Truth video game appears on screen] / Narrator: The South Park video game, coming to stores soon. / Butters: Yeah, and if you believe that I've got a big floppy wiener to dangle in your face.

- ^ Nicholson, Max (November 14, 2013). "The Console War is Coming..." IGN. Archived from the original on November 14, 2013. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- ^ Karmali, Luke (February 25, 2014). "South Park: The Stick of Truth Censored in Europe". IGN. Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- ^ Matulef, Jeffrey (February 25, 2014). "South Park: The Stick of Truth censored in Europe". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on November 26, 2015. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Moses, Toby (March 5, 2014). "Why has the South Park: Stick of Truth game been censored in Europe?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 11, 2014. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- ^ Bogos, Steven (February 27, 2014). "South Park: The Stick of Truth Will Be Censored In UK, Europe – Update". The Escapist. Archived from the original on February 28, 2014. Retrieved March 7, 2014.

- ^ Pitcher, Jenna (December 19, 2013). "Three mini-games removed from South Park: The Stick of Truth Australia, now features a crying Koala". Polygon. Archived from the original on April 6, 2014. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ^ MacDonald, Keza (March 5, 2014). "South Park, satire and us – by Matt Stone". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 11, 2014. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- ^ Bogos, Steven (March 29, 2014). "The Stick of Truth's Censorship Disabled by PC Mod – Update". The Escapist. Archived from the original on September 20, 2017. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- ^ a b "South Park: The Stick of Truth for PC Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on March 7, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ a b "South Park: The Stick of Truth for PlayStation 3 Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on March 7, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ a b "South Park: The Stick of Truth for Xbox 360 Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on March 7, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Elliot, Matthew (March 4, 2014). "Review: South Park – The Stick of Truth is shameless, hilarious and surprisingly complex". Computer and Video Games. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f "South Park: The Stick Of Truth review". Edge. March 4, 2014. Archived from the original on March 8, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ "South Park: The Stick of Truth Review". Game Informer. March 3, 2014. Archived from the original on August 8, 2019.

- ^ Liebl, Matt (March 4, 2014). "South Park: The Stick of Truth Review: Come on down and meet some friends of mine". GameZone. Archived from the original on April 6, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ Williamson, Steven (March 4, 2014). "South Park: The Stick of Truth Review – a side-splitting RPG with real character (Page 4)". PlayStation Universe. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- ^ Parfitt, Ben (March 10, 2014). "South Park: The Stick of Truth debuts at No.1". MCV. Archived from the original on April 1, 2014. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ^ Dring, Christopher (March 17, 2014). "Xbox One hardware jumps 96% on Titanfall launch". MCV. Archived from the original on April 1, 2014. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ^ Johnson, Erik (March 9, 2014). "Steam top ten sellers chart: March 2–8". MCV. Archived from the original on March 13, 2014. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- ^ Johnson, Erik (March 16, 2014). "Steam top ten sellers chart: March 9–15". MCV. Archived from the original on April 3, 2014. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- ^ Scammell, David (April 14, 2014). "Titanfall was March's top-selling game in the UK". VideoGamer.com. Archived from the original on April 15, 2014. Retrieved April 15, 2014.

- ^ Dring, Christopher (January 15, 2015). "Revealed: The 100 best-selling games of 2014 in the UK". MCV. Archived from the original on January 20, 2015. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ^ "Microsoft Sells More Than 5 Million Xbox Ones". NASDAQ. April 17, 2014. Archived from the original on April 18, 2014. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- ^ Sinclair, Brendan (May 15, 2014). "Ubisoft full-year sales shrink 20%". GamesIndustry. Archived from the original on May 17, 2014. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- ^ Jarvis, Matthew (January 16, 2015). "Destiny and Minecraft were the best-selling games on PlayStation Store in 2014". MCV. Archived from the original on January 18, 2015. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ^ Tan, Nicholas (May 12, 2015). "South Park: The Stick of Truth Sells a Whopping 1.6 Million Copies". Game Revolution. Archived from the original on July 17, 2015. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- ^ Futter, Mike (February 11, 2016). "Five Million Copies Of South Park: The Stick Of Truth Have Been Shipped". Game Informer. Archived from the original on February 14, 2016. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

- ^ "Game Critics Awards 2012 Winners". Game Critics Awards. 2012. Archived from the original on December 7, 2013. Retrieved March 7, 2014.

- ^ "2014 Navgtr Winners: Dragon 5, Alien/Mordor/South Park 4". National Academy of Video Game Trade Reviewers. February 16, 2015. Archived from the original on February 17, 2015. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ^ Robinson, Andy (August 29, 2014). "Golden Joysticks 2014 voting begins". Computer and Video Games. Archived from the original on September 1, 2014. Retrieved August 29, 2014.

- ^ Ivan, Tom (November 21, 2014). "Game Awards 2014 nominees announced". Computer and Video Games. Archived from the original on November 24, 2014. Retrieved November 21, 2014.

- ^ Van Ord, Kevin (December 5, 2014). "Dragon Age: Inquisition Wins GOTY at Game Awards". GameSpot. Archived from the original on December 6, 2014. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- ^ Mailberg, Emanuel (March 15, 2015). "Dragon Age Inquisition Wins Another Game of the Year Award". GameSpot. Archived from the original on March 16, 2015. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ "Dragon Age: Inquisition Takes Game of the Year at DICE Awards". The Escapist. February 6, 2015. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ^ * "Top 100 Games of a Generation". IGN. 2014. Archived from the original on May 21, 2014. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- "Top 100 Games of a Generation: #50 South Park: The Stick of Truth". IGN. 2014. Archived from the original on May 22, 2014. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- ^ "Giant Bomb's 2014 Game of the Year Awards: Day One". Giant Bomb. December 26, 2014. Archived from the original on October 27, 2016. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- ^ Perez, Daniel (December 30, 2014). "2014 Game of the Year 7: South Park: The Stick of Truth". Shacknews. Archived from the original on January 8, 2015. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ^ Maggs, Sam; Sapieha, Chad; Kaszor, Daniel (December 26, 2014). "Post Arcade's Games of the Year 2014: Number 7 – South Park The Stick of Truth". Financial Post. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ^ Stuart, Keith (December 19, 2014). "The 25 best video games of 2014". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 1, 2015. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ^ Hamilton, Kirk (December 16, 2014). "The Best Video Game Music Of 2014". Kotaku. Archived from the original on January 13, 2015. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ^ Nicholson, Max (September 12, 2017). "Top 100 Unforgettable Video Game Moments". IGN. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved September 12, 2017.

- ^ "The best RPGs of all time". PC Gamer. October 12, 2017. Archived from the original on October 12, 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- ^ "The Top 100 RPGs Of All Time". Game Informer. January 1, 2018. Archived from the original on January 2, 2018. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- ^ Yin-Poole, Wesley (June 15, 2015). "South Park: The Fractured but Whole". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on June 17, 2015. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- ^ O'Brien, Lucy (June 15, 2015). "E3 2015: South Park: The Fractured But Whole Announced". IGN. Archived from the original on June 16, 2015. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- ^ Knezevic, Kevin (October 16, 2017). "South Park: The Fractured But Whole Review Roundup". GameSpot. Archived from the original on November 4, 2017. Retrieved November 4, 2017.

- ^ Dwan, Hannah (October 16, 2017). "South Park: The Fractured But Whole review round up – What the critics are saying". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on November 4, 2017. Retrieved November 4, 2017.

- ^ Dornbush, Jonathon (March 22, 2018). "Ubisoft Announces Mumbai, Odesa Studios To Work On AAA Franchises". IGN. Archived from the original on April 24, 2018. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ^ Bowman, Jon (March 8, 2018). "South Park: The Fractured But Whole Coming To Switch April 24". Game Informer. Archived from the original on May 16, 2018. Retrieved March 20, 2019.