Props used in yoga include chairs, blocks, belts, mats, blankets, bolsters, and straps. They are used in postural yoga to assist with correct alignment in an asana, for ease in mindful yoga practice, to enable poses to be held for longer periods in Yin Yoga, where support may allow muscles to relax, and to enable people with movement restricted for any reason, such as stiffness, injury, or arthritis, to continue with their practice.

One prop, the yoga strap, has an ancient history, being depicted in temple sculptures and described in manuscripts from ancient and medieval times; it was used in Sopasrayasana, also called Yogapattasana, a seated meditation pose with the legs crossed and supported by the strap. In modern times, the use of props is associated especially with the yoga guru B. K. S. Iyengar; his disciplined style required props including belts, blocks, and ropes.

History

editThe yogapaṭṭa in sculpture

editThe practice of yoga as exercise is modern, though some of the asanas are ancient and many more are medieval. A band or strap of cloth was however used in ancient times, some 2000 years ago, to support the body in one asana in particular; this device was the yogapaṭṭa, a term defined in Monier Monier-Williams's Sanskrit-English dictionary. Such a strap is depicted in a relief sculpture on the Great Stupa of Sanchi in Madhya Pradesh, dated c. 50 BCE to 50 CE, in other sculptures from the 7th century CE at Mamallapuram and Ellora, and from the 14th century at Hampi.[2]

- In sculpture

-

Yogi (top right) using a strap, in relief sculpture of the Syama Jataka, the Great Stupa of Sanchi, c. 50 BCE to 50 CE

-

Yogi (centre) using strap around waist and legs, Mahabalipuram Caves, c. 7th century

The sopāśraya asana

editTextual evidence begins with the ancient bhāṣya commentary to the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, which names an asana called sopāśraya, meaning "with support"; this was interpreted by medieval commentators such as Vācaspati's 10th century Tattvavaiśāradī and Vijñānabhikṣu's 16th century Yogavarttika as meaning the use of a yogapaṭṭa strap.[2][3] The 19th century Śrītattvanidhi illustrates a seated posture named yogapaṭṭāsana, "the posture with yoga strap", with the band tied around the folded legs. Norman Sjoman states that this seems to have been an alternative meditation pose when the yogi's back needed additional support.[2][4]

- In illustrations

-

Sitting with a strap. Chawand, Rajasthan, 1605

-

yogapaṭṭāsana, "posture with yoga strap", in Sritattvanidhi, 19th century

The stambha meditation crutch

editShankara glosses the posture mentioned by Patanjali as "The One with Support is with a yoga strap or with a prop such as a crutch";[5] later commentators such as Vācaspati, Hemacandra and Vijñānabhikṣu speak of the posture only as using a strap. The scholar James Mallinson however comments that a crutch (stambha or adhari) is seen both in miniature paintings of yogis and in current use (in India).[5][6] Mallinson states that the meditation crutch was in wide use amongst ascetics from the 16th century onwards; he has travelled India visiting hatha yoga practitioners, and describes the use of the crutch as "rare today, but not unknown", providing a photograph of a yogi at the 2010 Kumbh Mela at Haridwar in evidence.[6]

-

Stambha meditation crutch in use by a yogi at the Kumbh Mela, Haridwar, in 2010. Detail of photograph by James Mallinson[6]

The 16th century Yogacintāmaṇī describes a posture, Nidrāharāsana "Posture to prevent sleep", where a fine balance is maintained with the lower legs crossed in Padmasana and the body upright from the knees (a form of Gorakshasana), and the hands holding a T-shaped prop.[7]

-

Nidrāharāsana, pose to prevent sleep, in the 19th century Yogāsana, using a T-shaped prop[7]

Modern practice

editFor correct alignment

editChairs and other props are used widely in some schools of modern yoga as exercise. The use of props was pioneered in Iyengar Yoga, to enable students to work with correct alignment both as beginners and in more advanced asanas with suitable support.[9] Iyengar Yoga was created by B. K. S. Iyengar, a pupil of the yoga pioneer Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, and described in his authoritative 1966 book Light on Yoga.[10] The scholar of religion Andrea Jain observes that the book "prescribed a thoroughly individualistic system of postural yoga",[11] one that was "rigorous and disciplined",[11] requiring props such as "belts, bricks, and ropes".[11] The props served to guide the practitioner rather than to provide support.[12]

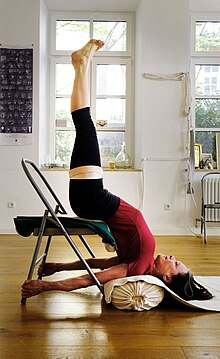

For example, in Iyengar Yoga, Sarvangasana, shoulder stand, can be practised under suitable supervision with the shoulders on a bolster, the buttocks supported on the seat of a chair and a blanket, and the legs resting on the top of the chair's back.[8]

For ease in practice

editThe founder of the OM Yoga Center, Cyndi Lee, describes the use of props as part of a practice of Mindful Yoga. She wrote that students accustomed to vinyasa yoga "would rather strain and grunt" trying to touch their toes, endangering their backs, rather than use props such as a yoga belt or block to reduce the strain or elevate the pelvis.[14] The students ignored her, thinking that "ease in their practice ... meant easy and that was wimpy. Not enough challenge, boring, too slow."[14] She found that this gradually changed as the students recognised duhkha, which she defines as the pain that comes from ignoring the reality of a situation. In her view, using yoga props was a form of ahimsa, the yogic practice of nonviolence, in this case avoiding having the will or ego fighting the body.[14]

For Yin Yoga

editThe teacher of Yin Yoga Bernie Clark wrote that many yoga students see props as "cheating",[13] perhaps feeling that since they are used in restorative yoga sessions, they are not suitable for other students. Clark counters that props offer multiple benefits, including increasing or decreasing stress in specific areas; creating length and space; making certain positions accessible; providing support and thus enabling muscles to release; and increasing comfort, enabling postures to be held for longer durations. These benefits are especially noticeable in a slower practice such as Yin Yoga.[13] Clark cites the founder of Insight Yoga, Sarah Powers, as writing that "when the bones feel supported, the muscles can relax".[13] He comments that highly experienced practitioners can easily miss out on this benefit, feeling that they have no need for props, but that even they may discover in "Butterfly Pose" (the Yin Yoga version of Baddha Konasana) that supporting the knees on blocks allows muscles they did not know they were engaging to relax, transferring the asana's stress to the fascia.[13] He lists a wide variety of props beyond those most commonly used, and suggests uses for them.[13]

To go deeper into a pose

editThe leading Iyengar yoga teacher Dean Lerner, in Yoga Journal, stated that the benefits of props depend on the experience, maturity, and ability of the practitioner; a mature student can enable "refined penetration into the pose and one's being".[15] Students may be afraid, he notes, of an inverted pose such as Shirshasana (yoga headstand); by practising against a wall, the student can learn to master the fear of falling, and can then continue practising there to develop stability, right alignment, and refined balance.[15] He adds that props can also be used to enable poses to be held for a longer duration, developing stability of mind and body, as well as poise and concentration; these, he states, enable the mind to draw inward and develop objectivity and humility, a step on the journey towards the Self.[15]

To prevent slipping

editThe yoga mat has become ubiquitous in the practice of yoga as exercise, to the extent that it may not even be thought of as a prop.[16] Its main function is "stickiness",[17] to prevent slipping, though it also provides a more comfortable surface such as for kneeling poses.[17] The mat may equally mark out a territory in a crowded class, or create a ritual space as it is unrolled to begin a session and rolled up at the end.[18][19]

When movement is restricted

editAlice Christensen's Easy Does It Yoga, first described in 1979, uses "chair exercises", alongside others on floor or bed, and in later editions also in swimming pools, for older practitioners with restricted movement.[20][21] Lakshmi Voelker-Binder created an approach named Chair Yoga in 1982, on seeing that one of her pupils, aged only in her thirties, was unable to do floor poses because of arthritis.[22][23]

Yoga as therapy is the use of asanas as a gentle form of exercise and relaxation, applied specifically with the intention of improving health. This may involve meditation, imagery, breath work (pranayama) and music alongside the exercise.[24] A 2013 systematic review found beneficial effects of yoga on low back pain.[25]

For aerial yoga

editAerial yoga, a yoga hybrid, requires the use of a silk hammock with straps attached by carabiners to support chains, to permit practitioners to perform variants of yoga poses without weight on their hands or feet.[26] Difficult mat-based yoga postures may prove easier to perform through aerial yoga, while the hammock's movement adds variety to the aerial workout.[27]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Das Studio" (in German). Yogashala Munchen. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ a b c Powell, Seth (June 2018). "The Ancient Yoga Strap". The Luminescent. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ The commentary is on Yoga Sutra 2.46, that an asana should be steady and comfortable.

- ^ Sjoman, Norman E. (1999) [1996]. The Yoga Tradition of the Mysore Palace. Abhinav Publications. p. 85, and plate 20. ISBN 978-81-7017-389-2.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Maas, Philipp A. (2018). "'Sthirasukham Asanam': Posture and Performance in Classical Yoga and Beyond". In Baier, Karl; Maas, Philipp A.; Preisendanz, Karin (eds.). Yoga in transformation: historical and contemporary perspectives. Göttingen: Vienna University Press. pp. 49–100. ISBN 978-3-8471-0862-7. OCLC 1077772000.

- ^ a b c Mallinson, James (2020). "Yogi Insignia in Mughal Painting and Avadhi Romances". In Orsini, Francesca; Lunn, David (eds.). To be published in: Objects, Images, Stories: Simon Digby's historical method (PDF). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b Birch, Jason (2024). "The Ujjain Yogacintāmaṇi". Āsanas of the Yogacintāmaṇi: The Largest Premodern Compilation on Postural Practice. Paris and Pondicherry: École française d'Extrême-Orient and Institut français de Pondichéry. p. 172, figure 7.

- ^ a b Mehta, Silva; Mehta, Mira; Mehta, Shyam (1990). Yoga: The Iyengar Way. Dorling Kindersley. pp. 118–119. ISBN 978-0863184208.

- ^ Mehta, Silva; Mehta, Mira; Mehta, Shyam (1990). Yoga the Iyengar Way: The new definitive guide to the most practised form of yoga. Dorling Kindersley. pp. 70–71, 80, 108, 118–119. ISBN 978-0863184208.

- ^ Goldberg, Michelle (23 August 2014). "Iyengar and the Invention of Yoga". The New Yorker. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ^ a b c Jain, Andrea (July 2016). "The Popularization of Modern Yoga". Oxford Research Encyclopedias. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.163. ISBN 978-0-19-934037-8. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- ^ Peters, Leslie (December 2006). "Proper Props". Yoga Journal (December 2006): 119–122. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Clark, Bernie (7 January 2015). "The Why, What & How Behind Using Yoga Props". Elephant Journal. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ a b c Lee, Cyndi (2004). Yoga Body, Buddha Mind. Riverhead Books. pp. 145–146.

- ^ a b c Lerner, Dean (28 August 2007). "The Nature and Use of Yoga Props". Yoga Journal. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ Upham, Becky (10 September 2019). "Yoga Mats, Straps, Bolsters, and Other Props to Aid Your Practice". Everyday Health. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

Medically Reviewed by Lynn Grieger, RDN CDCES

- ^ a b YJ Editors (12 April 2017). "Test Your Mat Savvy: 5 Teachers' Favorite Yoga Mats". Yoga Journal. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ Jain, Andrea (14 August 2015). "Five myths about yoga". The Washington Post.

- ^ Korpelainen, Noora-Helena (2019). "Sparks of Yoga: Reconsidering the Aesthetic in Modern Postural Yoga". Journal of Somaesthetics. 5 (1): 46–60.

- ^ Christensen, Alice (1979). Easy Does It Yoga for Older People. San Francisco and Cleveland: Harper and Row; Light of Yoga Society.

- ^ Christensen, Alice (1999). The American Yoga Association's Easy Does It Yoga: the safe and gentle way to health and well-being. New York: Fireside Book. pp. 63–91 and throughout. ISBN 978-0-684-84890-7. OCLC 41951264.

- ^ "About Lakshmi Voelker". Get Fit Where You Sit. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ Lehmkuhl, Lynn (2020). Chair Yoga for Seniors : stretches and poses that you can do sitting down at home. New York, New York: Skyhorse Publishing. Introduction, page 8. ISBN 978-1-5107-5063-0. OCLC 1134762765.

- ^ Feuerstein, Georg (2006). Jonathan Shear (ed.). The Experience of Meditation. St. Paul, Minnesota: Paragon House. p. 90.

- ^ Cramer, Holger; Lauche, Romy; Haller, Heidemarie; Dobos, Gustav (2013). "A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Yoga for Low Back Pain". The Clinical Journal of Pain. 29 (5): 450–460. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e31825e1492. PMID 23246998. S2CID 12547406.

- ^ Macmillan, A. (2014). "Quick Tips: What is Antigravity Yoga?". howstuffworks. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Singh, Ayesha (21 February 2015). "New Yoga Sutras". New Indian Express. Retrieved 25 July 2020.