The Grand Mosque seizure, also known as the siege of Calamity, was a siege that took place between 20 November and 4 December 1979 at the Grand Mosque of Mecca, the holiest Islamic site in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. The building was besieged by up to 600 militants under the leadership of Juhayman al-Otaybi, a Saudi anti-monarchy Islamist from the Otaibah tribe. They identified themselves as "al-Ikhwan" (Arabic: الإخوان), referring to the religious Arabian militia[5] that had played a significant role in establishing the Saudi state in the early 20th century.

| Grand Mosque seizure | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

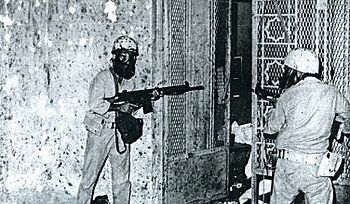

Saudi soldiers pushing into the underground corridor of the Grand Mosque of Mecca after gassing the interior with a non-lethal chemical agent provided by French specialists. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Supported by: |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| N/A | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~10,000 troops | 300–600 militants[8] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

| ||||||

|

11 pilgrims killed 109 pilgrims injured | |||||||

Location within Saudi Arabia | |||||||

The insurgents took hostages from among the worshippers and called for an uprising against the House of Saud, decrying their pursuit of alliances with "Christian infidels" from the Western world, and stating that the Saudi government's policies were betraying Islam by attempting to push secularism into Saudi society. They also declared that the Mahdi (a harbringer of the end of times) had arrived in the form of one of the militants' leaders, Muhammad Abdullah al-Qahtani.

Seeking assistance for their counteroffensive against the Ikhwan, the Saudis requested urgent aid from France, which responded by dispatching advisory units from the GIGN. After French operatives provided them with a special type of tear gas that dulls aggression and obstructs breathing, Saudi troops gassed the interior of the Grand Mosque and forced entry. They successfully secured the site after two weeks of fighting.[11]

In the process of retaking the Grand Mosque, the Saudi forces killed the self-proclaimed messiah al-Qahtani. Juhayman and 68 other militants were captured alive and later sentenced to death by Saudi authorities, being executed by beheading in public displays across a number of Saudi cities.[12][13] The Ikhwan's siege of the Grand Mosque, which had occurred amidst the Islamic Revolution in nearby Iran, prompted further unrest across the Muslim world. Large-scale anti-American riots broke out in many Muslim-majority countries after Iranian religious cleric Ruhollah Khomeini claimed in a radio broadcast that the Grand Mosque seizure had been orchestrated by the United States and Israel.[14]

Following the attack, Saudi king Khalid bin Abdulaziz enforced a stricter system of Islamic law throughout the country[15] and also gave the ulama more power over the next decade. Likewise, Saudi Arabia's Islamic religious police became more assertive.[16]

Background

editThe seizure was led by Juhayman al-Otaybi, a member of the Otaibah family, influential in Najd. He declared his brother-in-law Mohammed Abdullah al-Qahtani to be the Mahdi, or redeemer, who is believed to arrive on earth several years before Judgment Day. His followers embellished the fact that Al-Qahtani's name and his father's name are identical to the Prophet Mohammed's name and that of his father, and developed a saying, "His and his father's names were the same as Mohammed's and his father's, and he had come to Makkah from the north," to justify their belief. The date of the attack, 20 November 1979, was the last day of the year 1399 according to the Islamic calendar; this ties in with the tradition of the mujaddid, a person who appears at the turn of every century of the Islamic calendar to revive Islam, cleansing it of extraneous elements and restoring it to its pristine purity.[17]

Juhayman's grandfather, Sultan bin Bajad al-Otaybi, had ridden with Ibn Saud in the early decades of the century, and other Otaibah family members were among the foremost of the Ikhwan.[citation needed] Juhayman acted as a preacher, a corporal in the Saudi National Guard, and was a former student of Sheikh Abd al-Aziz Ibn Baz, who went on to become the Grand Mufti of Saudi Arabia.

Goals

editAl-Otaybi had turned against Ibn Baz "and began advocating a return to the original ways of Islam, among other things: a repudiation of the West; abolition of television and expulsion of non-Muslims."[18] He proclaimed that "the ruling Al-Saud dynasty had lost its legitimacy because it was corrupt, ostentatious and had destroyed Saudi culture by an aggressive policy of Westernization."[citation needed]

Al-Otaybi and Qahtani had met while imprisoned together for sedition, when al-Otaybi claimed to have had a vision sent by God telling him that Qahtani was the Mahdi. Their declared goal was to institute a theocracy in preparation for the imminent apocalypse. They differed from the original Ikhwan and other earlier Wahhabi purists in that "they were millenarians, they rejected the monarchy and condemned the Wahhabi ulama."[19]

Relations with ulama

editMany of their followers were from theology students at the Islamic University in Medina. Al-Otaybi joined the local chapter of the Salafi group Al-Jamaa Al-Salafiya Al-Muhtasiba (The Salafi Group That Commands Right and Forbids Wrong) in Medina headed by Sheikh Abd al-Aziz Ibn Baz, chairman of the Permanent Committee for Islamic Research and Issuing Fatwas at the time.[20] The followers preached their radical message in different mosques in Saudi Arabia without being arrested,[21] and the government was reluctant to confront religious extremists. Al-Otaybi, al-Qahtani and a number of the Ikhwan were locked up as troublemakers by the Ministry of Interior security police, the Mabahith, in 1978.[22] Members of the ulama (including Ibn Baz) cross-examined them for heresy but they were subsequently released as being traditionalists harkening back to the Ikhwan, like al-Otaybi's grandfather and, therefore, not a threat.[23]

Even after the seizure of the Grand Mosque, a certain level of forbearance by ulama for the rebels remained. When the government asked for a fatwa allowing armed force in the Grand Mosque, the language of Ibn Baz and other senior ulama "was curiously restrained." The scholars did not declare al-Otaybi and his followers non-Muslims, despite their violation of the sanctity of the Grand Mosque, but only termed them "al-jamaah al-musallahah" (the armed group). The senior scholars also insisted that before security forces attack them, the authorities must offer them the option to surrender.[24]

Preparations

editBecause of donations from wealthy followers, the group was well-armed and trained. Some members, like al-Otaybi, were former military officials of the National Guard.[25] Some National Guard troops sympathetic to the insurgents smuggled weapons, ammunition, gas masks and provisions into the mosque compound over a period of weeks before the new year.[26] Automatic weapons were smuggled from National Guard armories and the supplies were hidden in the hundreds of small underground rooms under the mosque that were used as hermitages.[27]

Seizure

editIn the early morning of 20 November 1979, the imam of the Grand Mosque, Sheikh Mohammed al-Subayil, was preparing to lead prayers for the 50,000 worshippers who had gathered for prayer. At around 5:00 am he was interrupted by insurgents who produced weapons from under their robes, chained the gates shut and killed two policemen who were armed with only wooden clubs for disciplining unruly pilgrims.[6] The number of insurgents has been given as "at least 500"[citation needed] or "four to five hundred", and included several women and children who had joined al-Otaybi's movement.[27]

At the time the Grand Mosque was being renovated by the Saudi Binladin Group.[28] An employee of the organization was able to report the seizure to the outside world before the insurgents cut the telephone lines.

The insurgents released most of the hostages and locked the remainder in the sanctuary. They took defensive positions in the upper levels of the mosque, and sniper positions in the minarets, from which they commanded the grounds. No one outside the mosque knew how many hostages remained, how many militants were in the mosque and what sort of preparations they had made.

At the time of the event, Crown Prince Fahd was in Tunisia for a meeting of the Arab League Summit. The commander of the National Guard, Prince Abdullah, was also abroad for an official visit to Morocco. Therefore, King Khalid assigned the responsibility to two members of the Sudairi Seven – Prince Sultan, then Minister of Defence, and Prince Nayef, then Minister of Interior, to deal with the incident.[29]

Siege

editSoon after the rebel seizure, about 100 security officers of the Ministry of Interior attempted to retake the mosque, but were turned back with heavy casualties. The survivors were quickly joined by units of the Saudi Arabian Army and Saudi Arabian National Guard. At the request of the Saudi monarchy, French GIGN units, operatives and commandos were rushed to assist Saudi forces in Mecca.[30]

By evening the entire city of Mecca had been evacuated.[dubious – discuss] Prince Sultan appointed Turki bin Faisal Al Saud, head of the Al Mukhabaraat Al 'Aammah (Saudi Intelligence), to take over the forward command post several hundred meters from the mosque, where Prince Turki would remain for the next several weeks. However, the first task was to seek the approval of the ulama, which was led by Abdul Aziz Ibn Baz. Islam forbids any violence within the Grand Mosque, to the extent that plants cannot be uprooted without explicit religious sanction. Ibn Baz found himself in a delicate situation, especially as he had previously taught al-Otaybi in Medina. Regardless, the ulema issued a fatwa allowing deadly force to be used in retaking the mosque.[7]

With religious approval granted, Saudi forces launched frontal assaults on three of the main gates. Again, the assaulting forces were repulsed. Snipers continued to pick off soldiers who revealed themselves. The insurgents aired their demands from the mosque's loudspeakers throughout the streets of Mecca, calling for the cut-off of oil exports to the United States and the expulsion of all foreign civilian and military experts from the Arabian Peninsula.[31] In Beirut, an opposition organization, the Arab Socialist Action Party – Arabian Peninsula, issued a statement on 25 November, alleging to clarify the demands of the insurgents. The party, however, denied any involvement in the seizure of the Grand Mosque.[32]

Officially, the Saudi government took the position that it would not aggressively retake the mosque, but rather starve out the militants. Nevertheless, several unsuccessful assaults were undertaken, at least one of them through the underground tunnels in and around the mosque.[33]

According to Lawrence Wright in the book The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11:

A team of three French commandos from the Groupe d'Intervention de la Gendarmerie Nationale (GIGN) arrived in Mecca. Because of the prohibition against non-Muslims entering the holy city, they converted to Islam in a brief, formal ceremony. The commandos pumped gas into the underground chambers, but perhaps because the rooms were so bafflingly interconnected, the gas failed and the resistance continued. With casualties climbing, Saudi forces drilled holes into the courtyard and dropped grenades into the rooms below, indiscriminately killing many hostages but driving the remaining rebels into more open areas where they could be picked off by sharpshooters. More than two weeks after the assault began, the surviving rebels finally surrendered.[34][35]

However, this account is contradicted by at least two other accounts,[36][page needed] including that of then GIGN commanding officer Christian Prouteau:[3] the three GIGN commandos trained and equipped the Saudi forces and devised their attack plan (which consisted of drilling holes in the floor of the Mosque and firing gas canisters wired with explosives through the perforations), but did not take part in the action and did not set foot in the Mosque.

The Saudi National Guard and the Saudi Army suffered heavy casualties. Tear gas was used to force out the remaining militants.[37] According to a US embassy cable made on 1 December, several of the militant leaders escaped the siege[38] and days later sporadic fighting erupted in other parts of the city.

The battle had lasted for more than two weeks, and had officially left "255 pilgrims, troops and fanatics" killed and "another 560 injured ... although diplomats suggested the toll was higher."[35] Military casualties were 127 dead and 451 injured.[9]

Aftermath

editPrisoners, trials and executions

editShortly after news of the takeover was released, the new Islamic revolutionary leader of Iran, Ayatollah Khomeini, told radio listeners, "It is not beyond guessing that this is the work of criminal American imperialism and international Zionism."[39][40] Anger fuelled by these rumours spread anti-American demonstrations throughout the Muslim world, noted occurring in the Philippines, Turkey, Bangladesh, eastern Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Pakistan.[14] In Islamabad, Pakistan, on the day following the takeover, the U.S. embassy in that city was overrun by a mob, which burned the embassy to the ground. A week later, in Tripoli, Libya, another mob attacked and burned the U.S. embassy.[41] Soviet agents also spread rumours that the U.S. was behind the Grand Mosque seizure.[42]

Al-Qahtani was killed in the recapture of the mosque, but Juhayman and 67 other insurgents who survived the assault were captured and later beheaded.[12] They were not shown any leniency.[13] The king secured a fatwa (edict) from the Council of Senior Scholars[12] which found the defendants guilty of seven crimes:

- violating the Masjid al-Haram's (the Grand Mosque's) sanctity;

- violating the sanctity of the month of Muharram;

- killing fellow Muslims and others;

- disobeying legitimate authorities;

- suspending prayer at Masjid al-Haram;

- erring in identifying the Mahdi;

- exploiting the innocent for criminal acts.[43][44]

On 9 January 1980, 63 rebels were publicly beheaded in the squares of eight Saudi cities[12] (Buraidah, Dammam, Mecca, Medina, Riyadh, Abha, Ha'il and Tabuk). According to Sandra Mackey, the locations "were carefully chosen not only to give maximum exposure but, one suspects, to reach other potential nests of discontent."[13]

Policies

editKhaled, however, did not react to the upheaval by cracking down on religious puritans in general, but by giving the ulama and religious conservatives more power over the next decade. Initially, photographs of women in newspapers were banned, then women on television. Cinemas and music shops were shut down. School curriculum was changed to provide many more hours of religious studies, eliminating classes on subjects like non-Islamic history. Gender segregation was extended "to the humblest coffee shop," and religious police became more powerful. Not until decades after the uprising would the Saudi government again begin making incremental reforms towards a more liberal society.[45][46]

See also

editReferences

editCitations

edit- ^ "Attack on Kaba Complete Video". 23 July 2011. Archived from the original on 13 November 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2013 – via YouTube.

- ^ Da Lage, Olivier (2006) [1996]. "L'Arabie Saoudite, pays de l'islam". Géopolitique de l'Arabie Saoudite. Géoppolitique des Etats du monde (in French). Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). Brussels, Belgium: Éditions Complexe. p. 34. ISBN 2-8048-0121-7 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b see also Prouteau, Christian (1998). Mémoires d'Etat (in French). Michel Lafon. pp. 265–277, 280. ISBN 978-2840983606.

- ^ Wright, Robin (December 1991). Van Hollen, Christopher (ed.). "Unexplored Realities of the Persian Gulf Crisis". Middle East Journal. 45 (1). Washington, D.C., U.S.: Middle East Institute: 23–29. ISSN 0026-3141. JSTOR 4328237.

- ^ a b Lacey 2009, p. 13.

- ^ a b Wright 2006b, p. 101.

- ^ a b Wright 2006b, pp. 103–104.

- ^ "The Siege at Mecca". 2006. Archived from the original on 6 July 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ a b "Pierre Tristam, '1979 Seizure of the Grand Mosque in Mecca', About.com". Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ^ Block, William; Block, Paul Jr.; Craig Jr., John G.; Deibler, William E., eds. (10 January 1980). Written at Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. "63 zealots beheaded for seizing mosque". World/Nation. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Vol. 53, no. 140. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S.: P.G. Publishing Co. Associated Press. p. 6. Retrieved 21 January 2022 – via Google Newspapers.

- ^ Benjamin, The Age of Sacred Terror (2002) p. 90

- ^ a b c d Roberts, Morris; Roberts, John M.; Rech, James W.; Reedy, Vince, eds. (10 January 1980). "Saudis behead zealots". The Victoria Advocate. Vol. 134, no. 247. Victoria, Texas, U.S.: Victoria Advocate Publishing Company. Associated Press. p. 6B. Retrieved 7 August 2012 – via Google Newspapers.

- ^ a b c Mackey, Sandra. The Saudis: Inside the Desert Kingdom. Updated Edition. Norton Paperback. W.W. Norton and Company, New York. 2002 (1st ed.: 1987). ISBN 0-393-32417-6 pbk., p. 234.

- ^ a b Wright 2001, p. 149.

- ^ Wright 2001, p. 155.

- ^ Lacey 2009, p. 48 "Those old men actually believed that the Mosque disaster was God's punishment to us because we were publishing women's photographs in the newspapers, says a princess, one of Khaled's nieces. The worrying thing is that the king [Khaled] probably believed that as well... Khaled had come to agree with the sheikhs. Foreign influences and bida'a were the problem. The solution to the religious upheaval was simple—more religion."

- ^ Benjamin, The Age of Sacred Terror, (2002) p. 90

- ^ Wright 2001, p. 152.

- ^ Commins, David (2009). The Wahhabi Mission and Saudi Arabia. I.B. Tauris. p. 63.

It is important to emphasize, however, that the 1979 rebels were not literally a reincarnation of the Ikhwan and to underscore three distinct features of the former: They were millenarians, they rejected the monarchy and they condemned the wahhabi ulama.

- ^ Lacey 2009, p. 9.

- ^ Wright 2006, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Lacey 2009, p. 31.

- ^ Wright 2006b, p. 103.

- ^ Lacey 2009, p. 30: "Their language was curiously restrained. The sheikhs had a rich vocabulary of condemnation that they regularly deployed against those who incurred their wrath, from kuffar ... to al-faseqoon (those who are immoral and who do not follow God). But the worst they could conjure up for Juhaymand and his followers was al-jamaah al-musallahah (the armed group). They also insisted that the young men must be given another chance to repent. ... Before attacking them, said the ulema, the authorities must offer the option`to surrender and lay down their arms.'"

- ^ Wright 2006b, p. 102.

- ^ Benjamin, The Age of Sacred Terror, (2002), p. 90

- ^ a b Wright 2006b, p. 104.

- ^ 1979 Seizure of the Grand Mosque in Mecca: The Attack and the Siege That Inspired Osama bin Laden Archived 7 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ Astal, Kamal M. (2002). "Three case studies: Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Iraq" (PDF). Pakistan Journal of Applied Sciences. 2 (3). Science Publications: 308–319. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ Irfan Husain (2012). Fatal Faultlines : Pakistan, Islam and the West. Rockville, Maryland: Arc Manor Publishers. p. 129. ISBN 978-1604504781. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ Wright 2006, p. 92.

- ^ JSTOR 3010802 Saudi Opposition Group Lists Insurgents' Demands] in MERIP Reports, No. 85. (February 1980), pp. 16–17.

- ^ "US embassy cable of 22 November" (PDF). Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ Tristam, Pierre. "1979 Seizure of the Grand Mosque in Mecca The Attack and the Siege That Inspired Osama bin Laden". about.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ^ a b Wright 2001, p. 148.

- ^ Trofimov, Yaroslav (2007). The Siege of Mecca: The 1979 Uprising at Islam's Holiest Shrine. Random House.

- ^ " US embassy cable of 27 November" (PDF). Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ "US embassy cable of 1 December" (PDF). Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ On This Day, 21 November, BBC

- ^ Kifner, John (25 November 1979). Sulzberger, Arthur Ochs Sr. (ed.). "Khomeini Accuses U.S. and Israel of Attempt to Take Over Mosques". The New York Times. New York City, New York, U.S. p. 1. ISSN 0362-4331. OCLC 1645522. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ [On 2 December 1979.] Embassy of the U.S. in Libya is Stormed by a Crowd of 2,000; Fires Damage the Building but All Americans Escape – Attack Draws a Strong Protest Relations Have Been Cool Escaped without Harm 2,000 Libyan Demonstrators Storm the U.S. Embassy Stringent Security Measures Official Involvement Uncertain, The New York Times, 3 December 1979

- ^ Soviet "Active Measures": Forgery, Disinformation, Political Operations (PDF). Bureau of Public Affairs (Report). Washington, D.C., U.S.: United States Department of State. 1 October 1981. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ Commins, David (2009). The Wahhabi Mission and Saudi Arabia. I.B. Tauris. p. 168.

- ^ Salamé, Ghassan (June 1987). Said, Edward; Abu-Lughod, Ibrahim (eds.). "Islam and Politics in Saudi Arabia". Arab Studies Quarterly. 9 (3). Association of Arab-American University Graduates/Institute of Arab Studies: 306–326. ISSN 0271-3519. JSTOR i40087865. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ Lacey 2009, pp. 49–52.

- ^ Tousignant, Lauren (6 November 2017). "Saudi women driving edition". News.com.au. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

Sources

edit- Lacey, Robert (2009). Inside the Kingdom: Kings, Clerics, Modernists, Terrorists, and the Struggle for Saudi Arabia. Penguin Group US. ISBN 9781101140734.

- Wright, Robin B. (2001). Sacred Rage: The Wrath of Militant Islam. Simon & Schuster.

- Wright, Lawrence (2006). The Looming Tower: Al Qaeda and the Road to 9/11. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-375-41486-2.

- Wright, Lawrence (2006b). The Looming Tower: Al Qaeda and the Road to 9/11. New York: Vintage. ISBN 978-1-4000-3084-2. (softcover)

Further reading

edit- Aburish, Said K., The Rise, Corruption, and Coming Fall of the House of Saud, St. Martin's (1996)

- Benjamin, Daniel, The Age of Sacred Terror by Daniel Benjamin and Steven Simon, New York : Random House, (c2002)

- Fair, C. Christine and Sumit Ganguly, "Treading on Hallowed Ground: Counterinsurgency Operations in Sacred Spaces", Oxford University Press (2008)

- Hassner, Ron E., "War on Sacred Grounds", Cornell University Press (2009) ISBN 978-0-8014-4806-5

- Kechichian, Joseph A., "The Role of the Ulama in the Politics of an Islamic State: The Case of Saudi Arabia", International Journal of Middle East Studies, 18 (1986), 53–71.

- Trofimov, Yaroslav, The Siege of Mecca: The Forgotten Uprising in Islam's Holiest Shrine and the Birth of Al Qaeda, Doubleday (2007) ISBN 0-385-51925-7 (Also softcover – Anchor, ISBN 0-307-27773-9)