Reality is the twenty-fourth studio album by the English musician David Bowie, originally released in Europe on 15 September 2003, and the following day in America. His second release through his own ISO label, the album was recorded between January and May 2003 at Looking Glass Studios in New York City, with production by Bowie and longtime collaborator Tony Visconti. Most of the musicians consisted of his then-touring band. Bowie envisioned the album as a set of songs that could be played live.

| Reality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 15 September 2003 | |||

| Recorded | January–May 2003 | |||

| Studio | Looking Glass (New York City) | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 49:25 | |||

| Label |

| |||

| Producer |

| |||

| David Bowie chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Reality | ||||

| ||||

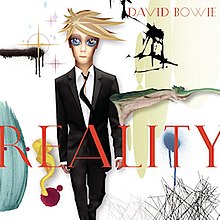

A mostly straightforward rock album with a more direct sound compared to its predecessor Heathen (2002), Reality contains covers of the Modern Lovers' "Pablo Picasso" and George Harrison's "Try Some, Buy Some". One of the tracks, "Bring Me the Disco King", dated back to 1992. A primary theme throughout Reality concerns reflections on ageing, while other songs focus on despaired and diminished characters. The cover artwork depicts Bowie as an anime-style character that exhibited the idea that reality had become an abstract concept.

Released under a variety of CD formats, Reality charted in numerous countries and reached number three in the United Kingdom. It failed to outperform Heathen in the United States, reaching number 29. The album was not supported through conventional single releases, although "New Killer Star" and "Never Get Old" appeared in some countries. Reality received largely positive reviews from music critics on release, with many highlighting the music, lyrics, vocal performances and the growing maturity in Bowie's songwriting.

Bowie supported the album on the worldwide A Reality Tour throughout 2003 and 2004, his biggest and final concert tour, which ended prematurely after Bowie was hospitalised for a blocked artery. Bowie thereafter largely retreated from public life and did not release another studio album until The Next Day in 2013, making Reality his last album of original material for ten years.

Recording and production

editWriting

editDavid Bowie began writing songs immediately after the Heathen Tour ended in October 2002. His new distribution deal with Columbia Records gave him the freedom to record at his own pace, so he was eager to return to the studio quickly. He elected to bring back Tony Visconti to co-produce the new album after the pair's successful renewed partnership with Heathen (2002).[1][2][3] He stated:[4]

We made Heathen our kind of debut reunion album. The circumstances, the environment, everything about it was just perfect for us to find out if we still had a chemistry that was really effective. And it worked out. It was perfect, not a step out of place, as though we had just come from the previous album into this one. It was quite stunningly comfortable to work with each other again.

Bowie and Visconti began initial ideas for the new album in November 2002. The success of the Heathen Tour rejuvenated Bowie's desire for touring, so the two fashioned the new album with the goal for the songs to be played live.[1][3][5] One of the first songs tracked was "Reality", which became the title of the new album.[2] The songwriting process itself was varied. Some tracks were written more conventionally, such as "She'll Drive the Big Car", while others were fashioned using a series of loops over a melody, such as "Looking for Water".[1] The length of time to write the songs also varied. "Fall Dog Bombs the Moon" was written in only 30 minutes,[4] while "Bring Me the Disco King" was written in 1992 and originally intended to appear on Black Tie White Noise (1993) before being slated for Earthling (1997) and finally completed for Reality.[2][5][6]

Sessions

editRecording for Reality began in early January 2003 at Looking Glass Studios in New York City, where Earthling and Hours (1999) were recorded. Bowie opted to use Looking Glass's smaller Studio B, which Visconti was renting on a semi-permanent basis, rather than the more spacious Studio A in order to have, in Visconti's words, a "real tight New York sound".[1][5] The studio was within close distance to Bowie's New York apartment, and his familiarity with the studio corresponded to relatively easy-going eight-hour working days, five days a week.[3][4] The urban landscape served as an influence on the new material, similar to how the mountainous Allaire Studios had influenced the recording of Heathen.[1]

The musicians mostly consisted of Bowie's then-touring band: Earl Slick and Gerry Leonard on guitar, Mark Plati on guitar and bass, Mike Garson on piano, and Sterling Campbell on drums; live bassist Gail Ann Dorsey and multi-instrumentalist Catherine Russell only contributed backing vocals.[1][3] Heathen guitarist David Torn provided "atmospheric" overdubs and lead guitar on "New Killer Star", while drummer Matt Chamberlain played on "Bring Me the Disco King" and "Fly".[a] Longtime Bowie guitarist Carlos Alomar also contributed overdubs to "Fly"; these overdubs were his final collaboration with Bowie.[1][5]

Bowie arrived with four to five basic home demos he had prepared; he told Sound on Sound: "I don't want my home to be taken over by the recording process. I'm very wary of that. I really saved everything for working over at Looking Glass."[4] He, Visconti and assistant engineer Mario J. McNulty initially worked on demos before the entire band arrived, many of which ended up in the final mixes, including Visconti's bass playing on "New Killer Star", "The Loneliest Guy", "Days" and "Fall Dog Bombs the Moon". McNulty's percussion on "Fall Dog Bombs the Moon" was also retained for the final mix.[1][4]

Similar to Heathen, Bowie played many instruments himself, including guitar, saxophone, Stylophone and keyboards, although Garson played prominently on "The Loneliest Guy" and "Bring Me the Disco King".[b][1][5] Like previous releases, bass, percussion and rhythm guitar parts were recorded live first from January and February, followed by vocals and overdubs from March to May 2003; Bowie, Plati and Campbell primarily played to click tracks from the demos.[1][4][5] Visconti brought back an old-fashioned 16-track analogue method of recording previously used on Heathen. Eight tracks were yielded after the initial eight-day session. Bowie revealed on his website in April that he had written 16 tracks, eight of which he was "mad for".[1][3][4]

Believing the drum tracks lacked the ambience and impact of Heathen's due to the studio, Bowie and Visconti travelled to Allaire and played the tracks back through the speakers to capture the same sound. This drum ambience is found sporadically throughout Reality, particularly on the cover of the Modern Lovers' "Pablo Picasso" and "Looking for Water".[1][4] Bowie recorded three separate vocal tracks for each track – one after the rhythm tracks were completed, another midway through the sessions and the final during mixing. Most tracks featured a single vocal take while others were stitched together from different ones. His vocals had also improved greatly due to Bowie having recently quit smoking; Visconti remarked that it regained "at least five semitones".[1][4][5]

Mixing

editMixing for Reality took place at Looking Glass under the direction of Visconti; Bowie no longer found a desire to contribute. Visconti used Studio B instead of Studio A as both he and Bowie were satisfied with the former's mixing boards. Similar to Heathen, the producer created both a standard stereo and 5.1 mix for release on SACD formats, which was made at Studio A.[1][4] Of the 5.1 mix, Visconti said:[4]

My approach to 5.1 is to be involved, to have instruments wrapped around you rather than in front of you. Rather than putting you in the audience seat I actually put you in the band, and so that's what I did with Reality. Also, I put a slap-back on the vocal in the rear speakers to again create space.

Music and lyrics

editCompared to Heathen, the music on Reality is mostly straightforward rock and pop rock,[1][5][8][9] with a more direct and aggressive sound.[10] Consisting of mostly original compositions, the album includes two cover songs originally slated for Bowie's scrapped follow-up to his 1973 covers album Pin Ups: the Modern Lovers' "Pablo Picasso", written by Jonathan Richman released on their eponymous studio album in 1976,[11] and George Harrison's "Try Some, Buy Some", originally recorded by Ronnie Spector in 1971 before Harrison recorded his own version in 1973.[4][12][13] Author James E. Perone writes that the two tracks match the album's autobiographical tones compared to other covers Bowie made throughout his career, which were more often chosen for similar musical styles.[14] Other covers recorded during the sessions included the Kinks' "Waterloo Sunset" and Sigue Sigue Sputnik's "Love Missile F1-11".[3][5][15] The principle sub-theme of Reality concerns thoughts on ageing.[14] Following an assortment of "extreme" characters from a "gluttonous rock star vampire" to various diminished figures, biographer Chris O'Leary draws comparisons to The Man Who Sold the World (1970).[5]

Songs

editThe opening track, "New Killer Star", recalls the "gentle beginnings" of Heathen before erupting into a groove. Pegg compares its guitar style to Bowie's own Diamond Dogs (1974) and Never Let Me Down (1987), as well as Blur's Think Tank (2003).[16] Lyrically, the song depicts the emotional and physical scarring of New York City following the September 11 attacks,[2][14] with lines such as "see the great white scar over Battery Park".[16] Pegg states that the second verse's juxtaposition of the real versus fake establishes a common theme throughout the entire album.[16] On covering "Pablo Picasso", Bowie explained that he enjoyed its "fantastically funny lyric".[11] With updated lyrics and new chords,[5] his rendition is more upbeat and rockier compared to the minimalist original, but remains tongue-in-cheek. Visconti's production utilises a wall of synthesisers against bursts of guitar and energetic percussion.[11]

"Never Get Old" features a guitar hook and bassline over echoing percussion. Recalling the themes and styles of Heathen, Low and "Heroes" (both 1977), the song presents a reflection on ageing and an expression on both desperation and denial.[5][14][17] Pegg notes that the thought of "never getting old" has been a mainstay in Bowie's songwriting, in tracks from "Changes" (1971) to "The Pretty Things Are Going to Hell" (1999), and considers "I think about this and I think about personal history" a "key line" for the entire Reality album.[17] "The Loneliest Guy" is the quietest and most reflective track on the album, which Pegg analyses as a "haunting meditation on memory, fortune and happiness".[7] Its subject is a loner who realises he is lucky, as he has no one else to look out for but himself. Bowie revealed that the imagery was inspired by the modernist city of Brasília; in his words, "a city taken over by weeds".[c][5]

"Looking for Water" combines Slick's "discordant guitar squeals" with a repetitive bassline and "metronomic" drums. Both Pegg and O'Leary found echoes of Never Let Me Down tracks, particularly "Glass Spider".[5][18] Similar to "New Killer Star", the song concerns post-9/11 nihilism.[18] Perone analyses it as symbolic of the basic necessities of life while the narrator is surrounded by the trappings of modern technology.[14] Like several of the album's tracks, "She'll Drive the Big Car" eavesdrops onto a wretched and despairing life in which a woman dreams of wealth but is stuck being a mundane house wife.[14][19] Musically, it is a funkier number reminiscent of Bowie's soul era, particularly tracks like "Golden Years" (1975).[19]

"Days" is a love song that continues the album's sub-themes of "weary retrospection and aging regret".[20] Bowie stated during a concert in Melbourne that "I sometimes feel I wrote this song for so many people".[5] It is musically simple, boasting a "faux-naif arrangement of low-tech synthesisers and twanging guitars against a jogging beat", compared by Pegg to the 1980s works of Soft Cell and Depeche Mode.[20] According to Bowie, the title of "Fall Dog Bombs the Moon" came from a Kellogg Brown & Root article and was subtle commentary on the then-emerging Iraq War.[21] He further described it as "an ugly song sung by an ugly man", whom he hinted as being then-US vice-president Dick Cheney.[5] Musically, the song contains similar rhythms and melodies as "New Killer Star" and Heathen.[5][14][21]

Bowie wanted to cover "Try Some, Buy Some" as far back as 1979 before finally doing so for Reality.[5] Pegg states that it unwittingly became a tribute to Harrison, who died in November 2001.[13] The arrangement on Bowie's version mostly stays true to the original, although in the artist's words, "the overall atmosphere is somewhat different".[12] Pegg and Perone contend that the "retrospective, older-and-wiser lyric" is appropriate for both Reality and Bowie himself.[14][13] The hard rock title track is the album's loudest and rockiest moment, recalling "Hallo Spaceboy" (1995) and Bowie's works with the rock band Tin Machine. The song adopts the artificial narrative that real life has no narrative, and its message, concerning how the quest for meaning in life is always doomed to fail, lies at the centre of the album's loose theme. Perone opines that it sees Bowie acknowledge that he hid behind personas and drugs throughout the early 1970s and is now facing reality.[14][22]

Pegg calls "Bring Me the Disco King" "one of the most idiosyncratic and strikingly dramatic numbers in the entire Bowie songbook".[6] Following its earlier incarnations, Bowie and Garson stripped the song down to a four-bar drum loop, vocal and piano, which the former felt worked best. Almost eight minutes in length, the song embraces a New York jazz sound that sees Garson playing an improvised piano solo similar to his one on "Aladdin Sane" (1973).[5][6][14] Representing a culmination of the album's lyrical themes, it offers fragmented images of, in Pegg's words, "creeping age, squandered opportunities, thwarted lives and impending dissolution".[6][14] The outtake "Fly" utilises a funky guitar riff for a tale about a middle-class family man who suffers from anxiety and depression, lyrically forestalling the "domestic American angst" of "New Killer Star" and "She'll Drive the Big Car".[5][23]

Title and artwork

editOn the concept of 'reality': it's a broken, fractured word now. It feels at times that there really is no sense any more, in a major way, and that everything is being broken down for us, and the absolutes have gone, and you end up with bits and pieces of what our culture was.[2]

Bowie announced the album title in June 2002.[1] Reflecting the ideal that reality has become an abstract concept,[4] he said that the title "encapsulate[s] the prosaic nature of the project itself".[2] The cover artwork was designed by Jonathan Barnbrook in collaboration with graphic artist Rex Ray; Barnbrook previously created the typography for Heathen, while Ray designed the artworks for Hours and the Best of Bowie compilation (2002). Ditching the airbrushed intellectualism of Heathen, Reality depicts Bowie in a cartoon, anime-style persona, with features typical of Japanese animation, including an exaggerated hairstyle, oversized eyes and simplified lines.[1] He steps forward against a background of various shapes, ink blobs, balloons and stars. Bowie compared it to Hello Kitty and bluntly stated in an interview: "The whole thing has a subtext of 'I'm taking the piss, this is not supposed to be reality'."[1]

Release

editIn the weeks prior to its release, the album was promoted on Bowie's website BowieNet through the posting of excerpts of each track, titled "Reality jukebox", while the Sunday Times released various CD-ROM featurettes. ISO and Columbia officially issued Reality in Europe and other territories on 15 September 2003, and in America the following day.[1] Like Heathen, it appeared in two CD formats: a single disc and a two-disc version with the outtakes "Fly" and "Queen of All the Tarts (Overture)", along with a studio re-recording of Bowie's 1974 single "Rebel Rebel"; the Japanese CD included "Waterloo Sunset" as a bonus track.[1] In the ensuing months other versions appeared, including a "Tour Edition" to coincide with the A Reality Tour in each territory the tour travelled to; the November European release included "Waterloo Sunset" and a DVD containing a complete performance of Reality from 8 September at Riverside Studios.[d]

The SACD release came in December 2003; EMI also issued a remixed SACD in September, which was packaged with Bowie's albums Ziggy Stardust (1972), Scary Monsters (1980) and Let's Dance (1983).[1] In February 2004, Columbia issued Reality on the new DualDisc format, containing the standard album on one side and the 5.1 mix in DVD-Audio format on the other. This release was initially restricted to the Boston and Seattle areas of the United States, with a worldwide release 12 months later. Reality did not receive an official release on vinyl until 2014 by the label Music on Vinyl.[1]

Commercial performance

editReality entered the UK Albums Chart at number three,[24] becoming Bowie's highest charting album in the UK since Black Tie White Noise ten years prior.[1] However, sales quickly fell after only four weeks.[2] The album topped the charts in Denmark and the Czech Republic,[1][25] and entered Billboard's European Top 100 Albums at number one.[26] Across Europe, Reality peaked at number two in France, Norway and Scotland,[27][28][29] number three in Austria, Belgium Wallonia and Germany,[30][31][32] number four in Belgium Flanders and Italy,[33][34] number five in Sweden and Switzerland,[35][36] number six in Ireland and Portugal,[37][38] and number eight in Finland.[39] It also reached number nine in Canada.[40]

It fared worse in other European countries, reaching number 14 in the Netherlands and number 25 in Spain.[41][42] Outside Europe, Reality charted at number 13 in Australia,[43] number 14 in New Zealand,[44] and number 47 in Japan.[45] In the US, Reality peaked at number 29 on the Billboard 200,[46] failing to replicate the success of Heathen, but outperforming Earthling and Hours.[1]

Singles

editReality was not supported through conventional single releases. Pegg opines that in the advent of Apple's iTunes, which was launched in April 2003, it was "already clear" that CD singles were becoming obsolete.[1] A music video for "New Killer Star" was released as a DVD-only single in the UK, US and other territories on 29 September 2003.[e] An audio-only version was issued as a conventional CD single in Canada, while the full-length album version appeared in Italy; both releases were backed by "Love Missile F1-11".[16] As the debut single, "New Killer Star" received extensive airplay during Bowie's television appearances for the album.[16]

"Never Get Old" was first previewed in France as early as June 2003 through a television advertisement for Vittel mineral water that featured Bowie himself. It was also posted online to BowieNet.[5][2][17] The song was originally scheduled to be released as the album's second single to coincide with Bowie's UK tour dates, but it was shelved at the last minute, similar to "Slow Burn" the previous year. Promotional CDs containing an edited version, backed by "Waterloo Sunset", appeared in Europe while in Britain, the two tracks appeared as digital downloads on Sony Music's UK site in November.[17] "Never Get Old" also appeared as a Japanese A-side in March 2004.[47] A mash-up of "Never Get Old" and "Rebel Rebel", created by Endless Noise the same month and titled "Rebel Never Gets Old", appeared in an ad campaign for Audi in America. This release appeared as a conventional single in June and reached number 47 in the UK.[48]

Critical reception

edit| Aggregate scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Metacritic | 74/100[49] |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | [50] |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | [51] |

| Entertainment Weekly | C+[52] |

| The Guardian | [53] |

| Mojo | [54] |

| Pitchfork | 7.3/10[55] |

| Rolling Stone | [56] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | [57] |

| Uncut | [9] |

| USA Today | [58] |

Reality received largely positive reviews from music critics on release.[1] Like many of the artist's most recent releases, several reviewers considered it his best since Scary Monsters,[8][54][59] although many made positive comparisons to Heathen.[1][60] A few felt Reality was stronger than its predecessor;[61][62] John Mulvey of Dotmusic wrote: "If Heathen was a little overpraised by relieved critics, then Reality is a more deserving case."[63] Pitchfork's Eric Carr further contested that "what last year's Heathen implied, and what Reality seems to prove, is that ... Bowie has finally joined us all in the present, mind-young as ever but old enough not to make a show of it".[55] He ultimately called the album "pretty good" and believed it cemented his status as a modern artist.[55] John Aizlewood of the Evening Standard found the album more cohesive than Heathen and named it the publication's CD of the week. Comparing it to Bowie's previous works, he argued that it stands on its own and with Reality, the artist has "rediscovered" himself and "regained his dignity".[64] Several also considered Reality a return to form for the artist.[60][64]

Some critics highlighted the lyrics and vocal performances as showcasing a maturity absent from previous works.[60][53][62] Several also commented on the music.[50] In the Miami Herald, Howard Cohen commended the artist for playing to his musical strengths rather than "hopping aboard some inappropriate youthful bandwagon".[62] In The Mail on Sunday, Tim De Lisle wrote that "this record pulsates with creative vigour", offering "a gleaming showcase for his voice, or rather voices."[1] Rolling Stone's Anthony DeCurtis believed Bowie succeeded in searching for "reality", to the artist's "mixed dismay and amusement".[56] Senior AllMusic editor Stephen Thomas Erlewine complimented the modernisation of Bowie and Visconti's former 1970s sound. While he called its predecessor an amalgamation of Hunky Dory to "Heroes", he found Reality picks up where its predecessor left off, creating a blend of "Heroes" to Scary Monsters.[50] Making further comparisons to Heathen, Erlewine felt Reality was "artier", but "similar in feel" and "just as satisfying". He concluded: "Both records are testaments to the fact that veteran rockers can make satisfyingly classicist records without resulting in nostalgia or getting too comfortable."[50] Remarking on the lyrics, Ryan Lenz of Associated Press described the album as "an exercise in introspection" and analysed Reality as not "a vehicle for commentary on contemporary times", but rather encapsulating an artist "nearing 60 and finding the world disappointingly clear and never what it seemed".[65]

It's a rather singular accomplishment that Reality makes the personal contemplation of mortality sound so crashingly, defiantly vital ... In short, it has all the alchemy of a great rock record – songs about death that were made to be played loud and live.[66]

Several reviewers praised the album as a whole. Uncut's Chris Roberts hailed Reality as "a very, very good sexy-angst album" filled with "lovely, left-handed songs, rich with unexpected angles, daring detours and words which muse over mortality yet emerge seeming upbeat", further summarising the lyrics as "mournful" and the music as "euphoric".[9] Andy Gill of The Independent described the album as a "satisfying, chunk solidity of songs" that starts well but ends poorly.[67] Caroline Sullivan of The Guardian praised Reality as "touching [and] intelligent" and that it "gels unexpectedly well".[53] Reviewing Reality for the BBC, Darryl Easlea enjoyed it as "direct, warm, emotional[ly] honest [...] [as well as] rather lively and convincing".[8] Meanwhile, The Observer's Kitty Empire cited "how wonderfully unforced it all sounds" as the album's defining feature. Although she found it inferior to the artist's Berlin-era works, she said Reality stands as "the first sequence of Bowie songs that bears repeated listening in years", concluding that "it is a pleasure, rather than a grim duty done out of respect for the memory of Ziggy Stardust".[60] Citing individual tracks, many praised the covers of "Try Some, Buy Some" and "Pablo Picasso".[56][67][62] AllMusic writer Thom Jurek even argued the two renditions "[distinguish] this set more than anything else".[68] The New York Times writer Mim Udovitch praised Visconti's production as "impeccable" and remarked on the sense of immediacy that "makes you feel that Mr. Bowie and his spectacularly hard-rocking band might be about to materialize in your living room ready for an encore".[66]

Nevertheless, some reviewers expressed more mixed assessments. Entertainment Weekly's Mark Weingarten cited the production as continuing to hinder Bowie's work since Black Tie White Noise, but nevertheless called the writing an improvement over his previous records.[52] In The Austin Chronicle, Marc Savlov contended that "While Reality isn't a failure by anyone's standards, there's precious few moments that you can recall, much less hum, an hour after listening to it."[69]

Tour

editBowie embarked on a world tour to support Reality that became his most extensive tour since the mid-1990s and, in terms of individual dates, the longest tour of his career.[70] Labelled "A Reality Tour", Pegg states that "the indefinite article emphasi[ses] the album's dalliance with the notion that there can be no absolute definition of reality."[70] The same musicians as the Heathen Tour and Reality—Slick, Garson, Dorsey, Russell and Campbell—returned for the new shows, with Leonard taking Plati's place as bandleader.[f] Rehearsals began in July 2003. The band spent most of late-August and September 2003 playing various gigs to promote the upcoming release of Reality; the first official show occurred in Copenhagen on 7 October.[2][70]

The tour's shows were more theatrical compared to preceding tours, being dominated by LED lights, raised catwalks and staircases. The setlist contained a variety of material across Bowie's entire career, ranging from classic hits to more obscure tracks.[70] Songs from both Reality and Heathen were included, while tracks like "Fantastic Voyage" (1979) made their live debut, and others like "Loving the Alien" (1984) were given radical reworkings. The band also swapped out songs throughout the shows and by the start of 2004, they had performed over 50 songs total.[70][2][71]

A Reality Tour received critical acclaim throughout its run; Pegg described it as one of his best concert tours. Two shows in Dublin were later released in 2010 on the A Reality Tour live album and DVD.[70] However, the tour suffered several setbacks throughout its duration, including the cancellation or postponement of shows in late 2003 due to Bowie contracting laryngitis and influenza, and even the death of a lighting technician in May 2004.[2][70][71] On 23 June, Bowie was forced to end the show early due to what medical personnel deemed a pinched shoulder nerve. Although he was back on stage two days later, his condition worsened and on 30 June, all 14 remaining dates were cancelled and A Reality Tour became his final concert tour.[3][2][70]

Aftermath and legacy

editReality finds Bowie returning, as he put it, "to the themes that have gnawed at me since I was a teenager – trying to find a sense of isolation, and a vague futurism." The result is not just a worthy successor to Heathen, but a fine and substantial addition to the canon, delivered with maturity, confidence and panache.[1]

In July 2004, it was revealed that Bowie had suffered a heart attack backstage and underwent a procedure known as angioplasty.[2][70][71] Following the incident, Bowie largely withdrew from the public eye. Over the following years, he was spotted at local New York venues and made occasional appearances at concerts by artists such as Franz Ferdinand, Arcade Fire and David Gilmour, with his final live public performance taking place in November 2006.[5][72] He occasionally contributed to various studio recordings by artists such as TV on the Radio and Scarlett Johansson, but did not release another studio album until The Next Day in 2013, making Reality his final album of original material for ten years.[5][73]

Reality has attracted generally positive assessments in subsequent years. In his 2005 book Strange Fascination, Buckley argues the album lacks both a "coherent musical identity" and "any thematic trajectory", furthermore observing a general feeling of "laxity" and underwritten songs, with the songs ranging from "good to merely pleasant", and "around a third" seeing Bowie "near top form".[2] On the other hand, Perone considers it a "strong album" and one that does have consistent themes throughout.[14] Author Paul Trynka writes that the record proves that, with the likes of tracks like "Bring Me the Disco King", Bowie "has the potential to conjure up pleasures as yet unknown".[74] Marc Spitz, writing before the release of The Next Day, found it worthy as a swan song to Bowie's long career.[61] Following that album's release, however, O'Leary argues that Reality reestablished itself as "a minor album whose songs were built to be blasted on stage".[5] The covers have also continued to receive praise.[14][75][76]

In The Complete David Bowie, Pegg states that one of the album's successes is that it emerges with a "reinvigorated sense of rock attack" following the "delicate, self-consciously artful[ness]" of its predecessor, equating both records to the relationships between Hunky Dory and Ziggy Stardust, or Outside (1995) and Earthling. Further comparing the two albums, he says Reality offers "less complexity and fewer sonic layers" than Heathen in exchange for "a greater abundance of catchy hooks and buoyant pop-rock atmospherics".[1] He also argues that Reality loses none of its predecessor's "artistic sensibility" and "its lasting value lies not just in its infectious melodies and evocative lyrics, but in the exquisitely judged oddness of its sonic textures".[1] In 2016, Bryan Wawzenek of Ultimate Classic Rock placed Reality at number 16 out of 26 in a list ranking Bowie's studio albums from worst to best, praising Bowie's comfortability on the record.[76] Including Bowie's two albums with Tin Machine, Consequence of Sound ranked Reality number 24 out of 28 in a 2018 list, with Pat Levy calling it "a decent record in the pantheon of Bowie, nothing more, nothing less".[75]

Track listing

editAll tracks are written by David Bowie, except where noted[1]

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "New Killer Star" | 4:40 | |

| 2. | "Pablo Picasso" | Jonathan Richman | 4:06 |

| 3. | "Never Get Old" | 4:25 | |

| 4. | "The Loneliest Guy" | 4:11 | |

| 5. | "Looking for Water" | 3:28 | |

| 6. | "She'll Drive the Big Car" | 4:35 | |

| 7. | "Days" | 3:19 | |

| 8. | "Fall Dog Bombs the Moon" | 4:04 | |

| 9. | "Try Some, Buy Some" | George Harrison | 4:24 |

| 10. | "Reality" | 4:23 | |

| 11. | "Bring Me the Disco King" | 7:45 | |

| Total length: | 49:25 | ||

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12. | "Waterloo Sunset" | Ray Davies | 3:28 |

| Total length: | 52:53 | ||

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Fly" | 4:10 |

| 2. | "Queen of All the Tarts (Overture)" | 2:53 |

| 3. | "Rebel Rebel" (Re-recording) | 3:11 |

| Total length: | 63:07 | |

Personnel

editAccording to biographers Nicholas Pegg and Chris O'Leary.[1][5]

- David Bowie – vocals; guitar; keyboards; synthesiser; saxophone; Stylophone; percussion; harmonica

- Gerry Leonard – guitar

- Earl Slick – guitar

- David Torn – guitar

- Mark Plati – bass guitar; guitar

- Sterling Campbell – drums

- Mike Garson – piano

- Gail Ann Dorsey – backing vocals

- Catherine Russell – backing vocals

Additional personnel

- Tony Visconti – guitar; keyboards; bass guitar; backing vocals

- Matt Chamberlain – drums on "Bring Me the Disco King" and "Fly"

- Mario J. McNulty – additional percussion and drums on "Fall Dog Bombs the Moon"

- Carlos Alomar – guitar on "Fly"

Production

- David Bowie – producer

- Tony Visconti – producer

- Mario J. McNulty – additional engineering

- Greg Tobler – assistant engineer

- Jonathan Barnbrook – cover design

- Rex Ray – illustration

Charts and certifications

edit

Weekly chartsedit

|

Year-end chartsedit

Certifications and salesedit

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

edit- ^ Chamberlain's drum part for "Bring Me the Disco King" was originally recorded during the Heathen sessions for the song "When the Boys Come Marching Home".[6]

- ^ Garson recorded his piano part for "The Loneliest Guy" at his home studio in Bell Canyon, California. He explained: "I recorded it on synthesiser originally and then took home the MIDI file and re-recorded it on my 9-foot Yamaha Disklavier, recording it as it played back."[7] He also rerecorded his part for "Bring Me the Disco King" at his home studio, but Bowie used his original Looking Glass performance instead.[6]

- ^ In his 2019 book Ashes to Ashes, O'Leary counters that modern-day Brasília's population had exceeded two million and is not consumed by nature. He instead likened the imagery of "The Loneliest Guy" to Bowie's Hunger City presented in Diamond Dogs, or the "capitalist wasteland" of Outside's "Thru These Architects' Eyes" (1995).[5]

- ^ The Canadian "Tour Edition", released in December 2003, only contained five songs on the DVD.[1]

- ^ As a DVD-only release, it was disqualified from singles charts.[16]

- ^ Plati departed to work with Robbie Williams.[2]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak Pegg 2016, pp. 450–459.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Buckley 2005, pp. 496–505.

- ^ a b c d e f g Thompson 2006, pp. 268–283.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Buskin, Richard (October 2003). "David Bowie & Tony Visconti Recording Reality". Sound on Sound. Archived from the original on 6 June 2015. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z O'Leary 2019, chap. 13.

- ^ a b c d e f Pegg 2016, pp. 50–52.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, pp. 169–170.

- ^ a b c Easlea, Daryl (2002). "David Bowie Reality Review". BBC. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ^ a b c Roberts, Chris (October 2003). "David Bowie: Reality". Uncut. p. 112. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 1 April 2022 – via Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ Giles, Jeff (16 September 2013). "Why David Bowie Became More Direct with 'Reality'". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 7 January 2022. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ a b c Pegg 2016, p. 206.

- ^ a b Peisner, David (15 July 2003). "Bowie Back With 'Reality': September set features Modern Lovers, Ronnie Spector covers". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 14 April 2018. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ a b c Pegg 2016, pp. 288–289.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Perone 2007, pp. 138–142.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 174.

- ^ a b c d e f Pegg 2016, pp. 194–195.

- ^ a b c d Pegg 2016, pp. 191–192.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, p. 172.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, pp. 241–242.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, pp. 72–73.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 220.

- ^ Pegg 2016.

- ^ a b "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Danishcharts.dk – David Bowie – Reality". Hung Medien. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Eurochart". Billboard. 4 October 2003. p. 65. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ^ a b "Lescharts.com – David Bowie – Reality". Hung Medien. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Norwegiancharts.com – David Bowie – Reality". Hung Medien. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Official Scottish Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Austriancharts.at – David Bowie – Reality" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Ultratop.be – David Bowie – Reality" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Offiziellecharts.de – David Bowie – Reality" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Ultratop.be – David Bowie – Reality" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Italiancharts.com – David Bowie – Reality". Hung Medien. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Swedishcharts.com – David Bowie – Reality". Hung Medien. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Swisscharts.com – David Bowie – Reality". Hung Medien. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Top 75 Artist Album, Week Ending 18 September 2003". Irish Recorded Music Association. Chart-Track. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ^ a b "Portuguesecharts.com – David Bowie – Reality". Hung Medien. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ a b "David Bowie – Reality" (ASP). finnishcharts.com. Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ a b "David Bowie Chart History (Canadian Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ a b "Dutchcharts.nl – David Bowie – Reality" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ a b Salaverrie, Fernando (September 2005). Sólo éxitos: año a año, 1959–2002 (in Spanish) (1st ed.). Madrid: Fundación Autor/SGAE. ISBN 84-8048-639-2.

- ^ a b "Australiancharts.com – David Bowie – Reality". Hung Medien. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Charts.nz – David Bowie – Reality". Hung Medien. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ a b "デヴィッド・ボウイ-リリース-ORICON STYLE-ミュージック" [Highest position and charting weeks of Reality by David Bowie]. oricon.co.jp (in Japanese). Oricon Style. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ a b "David Bowie Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 788.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 220–221.

- ^ "Reality by David Bowie". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 22 March 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- ^ a b c d Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Reality – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (2011). "Bowie, David". The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th concise ed.). London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-85712-595-8.

- ^ a b Weingarten, Mark (19 September 2003). "Reality". Entertainment Weekly. p. 85. Archived from the original on 5 July 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ a b c Sullivan, Caroline (12 September 2003). "David Bowie, Reality". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ a b "David Bowie: Reality Review". Mojo. No. 119. October 2003. p. 104.

- ^ a b c Carr, Eric (16 September 2003). "David Bowie: Reality Album Review". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 1 December 2011. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ a b c DeCurtis, Anthony (10 September 2003). "David Bowie: Reality". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ Sheffield, Rob (2004). "David Bowie". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). New York City: Simon & Schuster. pp. 97–98. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- ^ Gundersen, Edna (15 September 2003). "Listen Up (David Bowie: Reality)". USA Today. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ^ "David Bowie: Reality Review". Q. No. 207. October 2003. p. 101.

- ^ a b c d Empire, Kitty (14 September 2003). "Going through the emotions – David Bowie Reality". The Observer. p. 16. Retrieved 1 April 2022 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- ^ a b Spitz 2009, pp. 390–393.

- ^ a b c d Cohen, Howard (19 September 2003). "David Bowie: Reality (ISO/Columbia)". Miami Herald. p. 30. Archived from the original on 13 January 2023. Retrieved 13 January 2023 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- ^ Mulvey, John (15 September 2003). "reviews – albums – 'reality'". Dotmusic. Archived from the original on 11 October 2003. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ^ a b Aizlewood, John (9 September 2003). "David Bowie: Reality (ISO/Columbia)". Evening Standard. p. 69. Retrieved 1 April 2022 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- ^ Lenz, Ryan (21 September 2003). "David Bowie: Reality (ISO/Columbia)". Associated Press. Retrieved 1 April 2022 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- ^ a b Udovitch, Mim (14 September 2003). "Music; David Bowie Returns to Earth (Loudly)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ a b Gill, Andy (12 September 2003). "David Bowie: Reality (ISO/Columbia)". The Independent. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 1 April 2022 – via Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ Jurek, Thom. "David Bowie Box – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ Savlov, Marc (3 October 2003). "David Bowie: Reality Album Review". The Austin Chronicle. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Pegg 2016, pp. 618–626.

- ^ a b c Trynka 2011, pp. 462–465.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 626–635.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 460–470.

- ^ Trynka 2011, p. 496.

- ^ a b Levy, Pat (8 January 2018). "Ranking: Every David Bowie Album From Worst to Best". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ a b Wawzenek, Bryan (11 January 2016). "David Bowie Albums Ranked Worst to Best". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten 2003". Ultratop (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Archived from the original on 3 January 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ^ "Rapports annuels 2002". Ultratop (in French). Hung Medien. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ "Classement Albums – année 2003". Syndicat National de l'Édition Phonographique (in French). Archived from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ^ "The Official UK Albums Chart 2003" (PDF). UKChartsPlus. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ "French album certifications – David Bowie – Reality" (in French). Syndicat National de l'Édition Phonographique. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ "New Zealand album certifications – David Bowie – Reality". Recorded Music NZ. Retrieved 20 November 2024.

- ^ "British album certifications – David Bowie – Reality". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ Caulfield, Keith (21 November 2008). "Ask Billboard: Girls Aloud, David Bowie, Brits". Billboard. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ Breteau, Pierre (11 January 2016). "David Bowie en chiffres : un artiste culte, mais pas si vendeur". Le Monde. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

Sources

edit- Buckley, David (2005) [1999]. Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-7535-1002-5.

- O'Leary, Chris (2019). Ashes to Ashes: The Songs of David Bowie 1976–2016. London: Repeater Books. ISBN 978-1-912248-30-8.

- Pegg, Nicholas (2016). The Complete David Bowie (Revised and Updated ed.). London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-78565-365-0.

- Perone, James E. (2007). The Words and Music of David Bowie. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-99245-3.

- Spitz, Marc (2009). Bowie: A Biography. New York City: Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-71699-6.

- Thompson, Dave (2006). Hallo Spaceboy: The Rebirth of David Bowie. Toronto: ECW Press. ISBN 978-1-55022-733-8.[permanent dead link]

- Trynka, Paul (2011). David Bowie – Starman: The Definitive Biography. New York City: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-03225-4.