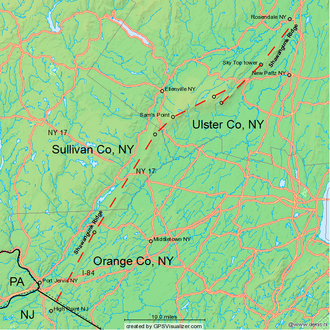

The Shawangunk Ridge /ˈʃɑːwəŋɡʌŋk/, also known as the Shawangunk Mountains or The Gunks,[1] is a ridge of bedrock in Ulster County, Sullivan County and Orange County in the state of New York, extending from the northernmost point of the border with New Jersey to the Catskills. The Shawangunk Ridge is a continuation of the long, easternmost section of the Appalachian Mountains; the ridge is known as Kittatinny Mountain in New Jersey, and as Blue Mountain as it continues through Pennsylvania. This ridge constitutes the western border of the Great Appalachian Valley.

| Shawangunk Ridge | |

|---|---|

| Shawangunk Mountains | |

Shawangunk Ridge from Sky Top cliff | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | High Point |

| Elevation | 2,289 ft (698 m) |

| Coordinates | 41°42′14″N 74°20′41″W / 41.70389°N 74.34472°W |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 47 mi (76 km) north–south |

| Geography | |

| |

| Country | United States |

| State | New York |

| Geology | |

| Rock age | Silurian (440 to 417 (±10) million years ago) |

| Rock type(s) | Shawangunk Formation; sedimentary |

The ridgetop, which widens considerably at its northern end, has many public and private protected areas, including Wurtsboro Ridge State Forest, Shawangunk Ridge State Forest, Minnewaska State Park Preserve, Witch's Hole State Park and Mohonk Preserve. The ridge is not heavily populated; its only settlement of consequence is the hamlet of Cragsmoor. In the past, the ridge was chiefly noted for mining and logging and a boom-era of huckleberry picking. Fires were regularly set to burn away the undergrowth and stimulate new growth of huckleberry bushes.

Today the ridge has become known for its outdoor recreation, most notably as one of the major rock climbing areas of North America, with many guides offering rock climbing trips in the area. Also known for its biodiversity and scenic character, the ridge has been designated by The Nature Conservancy as a significant area for its conservation programs.[2]

Etymology

editThe English name, Shawangunk, derives from the Dutch Scha-wan-gunk, the closest European transcription from the colonial deed record of the Munsee Lenape, Schawankunk (German orthography).

Lenape linguist Raymond Whritenour reports that schawan is an inanimate intransitive verb meaning "it is smoky air" or "there is smoky air". Its noun-like participle is schawank, meaning "that which is smoky air". Adding the locative suffix gives us schawangunk "in the smoky air".[3]

Whritenour has suggested that the name derives from the burning of a Munsee fort by the Dutch at the eastern base of the ridge in 1663 (a massacre ending the Second Esopus War). Use of the name spread quickly, and it was recorded in numerous land deeds and patents after the war. Historian Marc B. Fried writes:

It is conceivable that this was...the Indians' own proper name for their village [and fort] and that the name was appropriated for use in subsequent land dealings because of the proximity of the...tracts to the former Indian village....The second possibility is that the name simply came into existence in connection with the Bruyn [purchase of Jan., 1682, the first appearance of the name in documentary record], as a phrase invented by the Indians to describe some feature of the landscape.[4]

Fried also notes that the name's swift spread in the deed record suggests it was in use as a proper name before the Bruyn purchase. Shawangunk appears nowhere in reference to the fort in the extensive, translated Dutch record of the Second Esopus War. Shawangunk became associated with the ridge during the 18th century.

In the original Lenape, the word is tri-syllabic, Sha-wan-gun, although in an occasional 18th-century deed it is written with a fourth syllable.[5] The correct pronunciation approximates sha (short a) - wan (as in want) - goon (as in book).[6] The trailing k is sub vocal and modifies the sound of the n.[7]

European colonists began to truncate Shawangunk into "Shongum" (/ˈʃɒnɡʌm/ SHON-gum). Shongum was mistakenly identified as the Munsee pronunciation by the Reverend Charles Scott writing on Shawangunk's etymology for the Ulster County Historical Society in 1861.[8] The error has been reinforced in ethnographic sources and ridge literature, and by historians, librarians, and ridge educators for more than 140 years.

Both "Shawangunk" and "Shongum" are popular usages among locals native to the region. The "Gunks" is also a widely used familiar term for the ridge and has been in use at least since the mid-19th century. In a letter dated August and postmarked August 8, 1838, Hudson River School painter Thomas Cole corresponding with painter A.B. Durand writes, "Do let me hear from you when you get among the Gunks. I hope you will find every thing there your heart can wish."[9] The Shawangunks, particularly around Lake Mohonk, were the subject for several Hudson River School painters.

Geography

editThe Shawangunk Ridge is the northern end of a long ridge within the Appalachian Mountains that begins in Virginia, where it is called North Mountain, continues through Pennsylvania as Blue Mountain, becomes known as the Kittatinny Mountains after it crosses the Delaware Water Gap into New Jersey and becomes the Shawangunks at the New York state line. These mountains mark the western and northern edge of the Great Appalachian Valley.[1]

The ridge is widest (7.5 miles (12.1 km)) near the northern end and narrow in the middle (1.25 miles (2.01 km)), with a maximum elevation of 2,289 feet (698 m) near Lake Maratanza. The ridge rises above a broad, high plain which stretches to the Hudson River to the east. On the west the low foothills of the Appalachian Mountains mingle with a low flat made by the Rondout Creek and Sandburgh Creek, the Basha Kill and various small kills, as well as the Neversink River and Delaware River at the southern end. These adjacent valleys are underlain by relatively weak sedimentary rock (e.g., sandstone, shale, limestone).

Natural environment

editThere is an unusual diversity of vegetation on the ridge, containing species typically found north of this region alongside species typically found to the south or restricted to the Coastal Plain. The results is an area where many regionally rare plants are found at or near the limits of their ranges. Other rare species found in the area are those adapted to the harsh conditions on the ridge. Upland communities include chestnut oak and mixed-oak forest, pine barrens including dwarf pine ridges, hemlock-northern hardwood forest, and cliff and talus slope and cave communities. Wetlands include small lakes and streams, bogs, pitch pine-blueberry peat swamps, an inland Atlantic white cypress swamp, red maple swamps, acidic seeps, calcareous seeps, and a few emergent marshes.[10]

Geology

editThe ridge is primarily Shawangunk Conglomerate, a hard, silica-cemented sedimentary conglomerate of white quartz pebbles and sandstone that directly overlies the Martinsburg Formation, a thick sequence of turbidite deposits of dark gray shale and greywacke. The Martinsburg Formation was deposited in a deep ocean basin during the Ordovician (470 million years ago). The Shawangunk Conglomerate was deposited over the Martinsburg Formation in thick braided river deposits during the Silurian (about 420 million years ago); both sequences of sedimentary rock were subsequently deformed in a continental collision associated during the assembly of the Pangean supercontinent during the Permian (about 270 million years ago). This collision deformed strata within the ridge in a northward plunging series of asymmetric folds (e.g., anticlines and synclines) that are inclined gently westward. These same folds, involving strata that overlie the Shawangunk Conglomerate, are exposed north of Shawangunk Ridge in the Rosendale Natural Cement Region, where they can be directly examined in abandoned mines. Strata along the eastern margin of Shawangunk Ridge are truncated by erosion, resulting in the prominent cliffs characteristic of Shawangunk Ridge. The Shawangunk Conglomerate is very hard and resistant to weathering; whereas the underlying shale erodes relatively easily. Thus, the quartz conglomerate forms cliffs and talus slopes, particularly along the eastern margin of the ridge.

The entire ridge was glaciated during the last Wisconsin glaciation, which scoured the ridges, left pockets of till, and dumped talus (blocks of rock) off the east side of the ridge. On top of the ridge, the soils are generally thin, highly acidic, low in nutrients, and droughty, but in depressions and other areas where water is trapped by the bedrock or till, there are interspersed lakes and wetland areas. Soils on top of shale are thicker, less acidic, and more fertile. Topography on the top of the northern Shawangunks is irregular due to a series of faults that form secondary plateaus and escarpments.

Ice caves

editIce caves are deep fissures in the conglomerate bedrock that retain ice through much of the summer, resulting in a cool microenvironment that supports several northern species such as black spruce, hemlock, rowan, and creeping snowberry (Gaultheria hispidula), and bryophytes such as Isopterygium distichaceum. These ice caves are concentrated near Sam's Point in the northern Shawangunks. Larger limestone caverns occur along the lower slopes of the Rondout and Delaware River valleys.[12]

Lakes

editLakes and wetlands occur mostly on the flat-topped ridges at the northern and southern ends of the area and, to a lesser extent, along the western side of the middle part of the ridge. Lakes and ponds occurring on conglomerates tend to be clear, nutrient-poor, and very acidic, due to the limited buffering capacity of the bedrock. The northern Shawangunks have five lakes, the "sky lakes," which are, from north to south: Mohonk Lake, Lake Minnewaska, Lake Awosting, Mud Pond, and Lake Maratanza.[13] The pH in four of the lakes averages about 4 (acidic); Lake Mohonk, which partially overlays shale bedrock and is therefore partially buffered, is closer to neutral pH (7.0).

Public lands and preserves

editThe Shawangunks contain mainly public lands as well as several small residential areas. A large portion of the northern Ridge is protected by Minnewaska State Park Preserve, which also now manages Sam's Point Preserve with more than 100 miles (160 km) of hiking trails and several climbing areas. Established in 1963, the Mohonk Preserve[14] protects and manages over 8,000 acres of the Shawangunk Ridge, including the world-renowned Trapps climbing cliffs, and features over 70 miles of historic carriage roads and trails. In 2007 Shawangunk Ridge State Forest and Witches Hole State Forest were added. The Long Path long-distance hiking trail follows the ridge from Sullivan County to the vicinity of Kerhonkson; south of it the Shawangunk Ridge Trail connects to the Appalachian Trail near High Point. There are several old carriage trails on the Ridge including; Smiley Road from Ellenville into Minnewaska State Park Preserve; and Old Plank Road and Old Mountain Road in Shawangunk Ridge State Forest. Many of the foot trails are updated and maintained by the New York-New Jersey Trail Conference.

There are also many waterfalls in the Shawangunk region, such as: VerKeerderkill Falls, Awosting Falls, and Vernooy Kill Falls.

In 2004, a luxury development plan for buildings has threatened the ridge line, and as a result a grassroots "Save the Ridge" campaign has become extremely popular in the area. In 2006 a court ordered the sale of property by the private owner to settle a case brought on by the developer. The Open Space Institute of NY purchased the land and has signed it over to Minnewaska State Park Preserve.

The Trust for Public Land and Open Space Institute actually agreed to purchase the land for $17 million. At closing, however, the contract was assigned and title was taken in the name of the Palisades Interstate Park Commission, a federally chartered commission, although the funds for the purchase apparently came from the New York state Environmental Protection Fund.

Unlike the major public land holdings on the Shawangunk Ridge, the Mohonk Preserve is a private land trust[15] requiring a day fee depending on use.[16]

Unit Management Plan

editIn May 2007 the state Department of Environmental Conservation initiated the development of its Shawangunk Ridge Unit Management Plan to include Shawangunk Multiple Use Area, Witch's Hole State Forest, Shawangunk Ridge State Forest, Roosa Gap State Forest, Wurtsboro Ridge State Forest, Huckleberry Ridge State Forest, and three detached Forest Preserve parcels.

The goal of the project was to develop "management objectives" for the properties, including those concerning permissible forms of public recreation and access.[17]

Following an announcement of the project's launch, no further statements had been issued by the DEC regarding its work as of June 2009.

Recreation

editHiking

editThe Shawangunk Ridge Trail heads north approximately 40 miles (64 km), to Sam's Point Preserve in New York from the Appalachian Trail at High Point State Park in New Jersey. It generally follows the spectacular Shawangunk Ridge north, occasionally using abandoned roads and rail beds. The New York/New Jersey Trail Conference lists seventeen recommended hikes on the Ridge.

Other recreational activities

editThe development of rock climbing in the Shawangunks is attributed to Fritz Wiessner and Hans Kraus, pioneers of modern rock climbing.[18][19][20][21] It has historically been centered around four major cliffs: Millbrook, the Near Trapps, The Trapps, and Skytop. Of these four, The Trapps, is the longest, the most popular and most accessible, with the largest number of climbing routes.[22] The Near Trapps is located immediately across Route 44/55 from The Trapps, and is second in popularity.[23] Millbrook Mountain, the highest and most southerly cliff, is the most remote, and sees the least climbing activity.[24] The Skytop cliff is owned by the Mohonk Mountain House and rock climbing requires authorized guides. Rock climbing is also permitted on the Peterskill and Dickie Barre cliff areas of Minnewaska State Park Preserve.[25] The height of the cliff varies along the ridgeline, to a maximum of some 300 feet (91 m).

Fire lookout towers

editGraham tower

editIn 1930, the Conservation Department built a 60-foot-tall (18 m) Aermotor LS40 steel fire lookout tower and observers cabin on Sayers Hill (Pocatello Mountain). The tower was purchased with funds provided from the county and town, to protect the eastern and southern slopes of the Shawangunk Ridge. The tower was dismantled and moved to its current location in 1948. The tower ceased fire lookout operations at the end of the 1988 fire lookout season. It was officially closed in early 1989 by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. The Graham Lookout Tower is listed on the National Historic Lookout Register. The tower remains, but both it and the surrounding area are closed to the public.[26]

High Point tower

editIn 1912, the Conservation Commission built a wood fire lookout tower on the ridge east of Ellenville on High Point. In 1919, the Conservation Commission replaced it with a 47-foot-tall (14 m) Aermotor LS40 steel fire lookout tower. Due to increased use of aerial detection, the tower ceased fire lookout operation at the end of the 1971 fire lookout season, and was later removed.[26]

Roosa Gap tower

editIn 1948, the Conservation Department built a 35-foot-tall (11 m) Aermotor steel fire lookout tower on the ridge northeast of Wurtsboro. Due to increased use of aerial detection, the tower ceased fire lookout operations at the end of the 1972 fire lookout season. The tower was later sold, and is now closed to the public.[26]

References

edit- ^ a b Swain, Todd (2004-12-01). The Gunks Guide. Regional Rock Climbing. Falcon Guides. ISBN 0762738367.

- ^ Eastern: Shawangunk Mountains, The Nature Conservancy

- ^ Spatz, Christopher Spring 2005, "Smoke Signals", Shawangunk Watch

- ^ Fried, Marc B., 2005. Shawangunk Place-Names, pp.5-6

- ^ Ulster County archives

- ^ Susan B. Wick - Clove Valley Leni Lenape' historian and medicine woman.

- ^ Touching Leaves Woman et al. Delaware linguists

- ^ Spatz, Christopher Fall/Winter 2006, "The Vast Shon-gum Conspiracy," Shawangunk Watch

- ^ Document of the Daniel Smiley Research Center, Mohonk Preserve via New York State Museum

- ^ "Significant Habitats and Habitat Complexes of the New York Bight Watershed", US Fish & Wildlife Service

- ^ Shattuck, G.B. (1907) Some Geological Rambles Near Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, The Vassar College Press. page 10. Retrieved 2014-01-31.

- ^ Waterman, Laura and Guy (1993) Yankee Rock and Ice

- ^ "Life returns to the Shawangunk waters with the easing of acidification - Hudson Valley One". 2020-06-06. Retrieved 2022-04-10.

- ^ Mohonkpreserve.org

- ^ "Mohonk Preserve 50th Anniversary | Mohonk Preserve". www.mohonkpreserve.org. Archived from the original on 2015-12-19. Retrieved 2016-01-20.

- ^ "Hours and Fees | Mohonk Preserve". www.mohonkpreserve.org. Retrieved 2016-01-20.

- ^ DEC to Initiate Draft Shawangunk Ridge Unit Management Plan, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, 2007-05-11

- ^ [1] at Google Books — Chapter 16

- ^ "Fritz Wiessner; Anfangszeit; Ein neuer Standard; Nichtsteigen; Späteren Jahren; Persönliches". mussenstellen.com (in German). Retrieved 2017-01-29.

- ^ [2], p. PA195, at Google Books

- ^ "Dr. Hans Kraus, 90, Originator Of Sports Medicine in U.S., Dies". The New York Times. 1996-03-07. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-04-10.

- ^ Williams, Dick (2004), The Climber's Guide to the Shawangunks - The Trapps (3rd ed.), High Falls, NY: Vulgarian Press, p. 42, ISBN 0-9646949-1-3

- ^ Williams, Dick (2008), The Climber's Guide to the Shawangunks - The Near Trapps - Millbrook (2nd ed.), High Falls, NY: Vulgarian Press, p. xxxiv, ISBN 978-0-9646949-2-7

- ^ Williams, Dick (2008), The Climber's Guide to the Shawangunks - The Near Trapps - Millbrook (2nd ed.), High Falls, NY: Vulgarian Press, p. 230, ISBN 978-0-9646949-2-7

- ^ Crothers, David (15 April 2013). "Minnewaska's Dickie Barre Area Open To Climbing". Climberism. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ^ a b c "Searchable list of NY Fire Towers". nysffla.org. The New York State Chapter of the Forest Fire Lookout Association. Retrieved December 11, 2021.