In seismology, strong ground motion is the strong earthquake shaking that occurs close to (less than about 50 km from) a causative fault. The strength of the shaking involved in strong ground motion usually overwhelms a seismometer, forcing the use of accelerographs (or strong ground motion accelerometers) for recording. The science of strong ground motion also deals with the variations of fault rupture, both in total displacement, energy released, and rupture velocity.

As seismic instruments (and accelerometers in particular) become more common, it becomes necessary to correlate expected damage with instrument-readings. The old Modified Mercalli intensity scale (MM), a relic of the pre-instrument days, remains useful in the sense that each intensity-level provides an observable difference in seismic damage.

After many years of trying every possible manipulation of accelerometer-time histories, it turns out that the extremely simple peak ground velocity (PGV) provides the best correlation with damage.[1][2] PGV merely expresses the peak of the first integration of the acceleration record. Accepted formulae now link PGV with MM Intensity. Note that the effect of soft soils gets built into the process, since one can expect that these foundation conditions will amplify the PGV significantly.

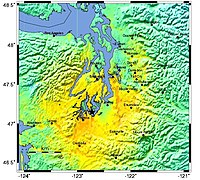

"ShakeMaps" are produced by the United States Geological Survey, provide almost-real-time information about significant earthquake events, and can assist disaster-relief teams and other agencies.[3]

Correlation with the Mercalli scale

editThe United States Geological Survey created the Instrumental Intensity scale, which maps peak ground velocity on an intensity scale comparable to the felt Mercalli scale. Seismologists all across the world use these values to construct ShakeMaps.

| Instrumental Intensity |

Velocity (cm/s) |

Perceived shaking | Potential damage |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | < 0.0215 | Not felt | None |

| II–III | 0.135 – 1.41 | Weak | None |

| IV | 1.41 – 4.65 | Light | None |

| V | 4.65 – 9.64 | Moderate | Very light |

| VI | 9.64 – 20 | Strong | Light |

| VII | 20 – 41.4 | Very strong | Moderate |

| VIII | 41.4 – 85.8 | Severe | Moderate to heavy |

| IX | 85.8 – 178 | Violent | Heavy |

| X+ | > 178 | Extreme | Very heavy |

Notable earthquakes

edit| PGV (max recorded) |

Mag | Depth | Fatalities | Earthquake |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 318 cm/s[4] | 7.7 | 33 km | 2,415 | 1999 Jiji earthquake |

| 215 cm/s[5] | 7.8 | 10 km | 62,013 | 2023 Turkey-Syria Earthquakes |

| 183 cm/s[6] | 6.7 | 18.2 km | 57 | 1994 Northridge earthquake |

| 170 cm/s[4] | 6.9 | 17.6 km | 6,434 | 1995 Great Hanshin earthquake |

| 152 cm/s[4] | 6.6 | 10 km | 11 | 2007 Chūetsu offshore earthquake |

| 147 cm/s[4] | 7.3 | 1.09 km | 3 | 1992 Landers earthquake |

| 145 cm/s[4] | 6.6 | 13 km | 68 | 2004 Chūetsu earthquake |

| 138 cm/s[4] | 7.2 | 10.5 km | 356 injured | 1992 Cape Mendocino earthquakes |

| 117.41 cm/s | 9.1[7] | 29 km | 19,747 | 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami |

| 108 cm/s[8] | 7.8 | 8.2 km | 8,857 | April 2015 Nepal earthquake |

| 38 cm/s[9] | 5.5 | 15.5 km | 0 | 2008 Chino Hills earthquake |

| 20 cm/s (est)[10] | 6.4 | 10 km | 115-120 | 1933 Long Beach earthquake |

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "INSTRUMENTAL SEISMIC INTENSITY MAPS". Archived from the original on 2000-09-03.

- ^ Wu, Yih-Min; Hsiao, Nai-Chi; Teng, Ta-Liang (July 2004). "Relationships between Strong Ground Motion Peak Values and Seismic Loss during the 1999 Chi-Chi, Taiwan Earthquake". Natural Hazards. 32 (3): 357–373. Bibcode:2004NatHa..32..357W. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.470.4890. doi:10.1023/B:NHAZ.0000035550.36929.d0. S2CID 53479793.

- ^ "ShakeMaps". Archived from the original on 2014-03-30. Retrieved 2014-04-01.

- ^ a b c d e f "How Fast Can the Ground Really Move?" (PDF). INSTITUTE FOR DEFENSE ANALYSES. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 1, 2022. Retrieved 2021-11-03.

- ^ https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us6000jllz/shakemap/analysis [bare URL]

- ^ "ShakeMap Scientific Background". Archived from the original on 2011-06-23. Retrieved 2021-11-03.

- ^ "M9.1 – Tohoku, Japan". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2021-11-03.

- ^ Takai, Nobuo; Shigefuji, Michiko; Rajaure, Sudhir; Bijukchhen, Subeg; Ichiyanagi, Masayoshi; Dhital, Megh Raj; Sasatani, Tsutomu (26 January 2016). "Strong ground motion in the Kathmandu Valley during the 2015 Gorkha, Nepal, earthquake. Earth Planets Space 68, 10 (2016)". Earth, Planets and Space. 68 (1). Takai, N., Shigefuji, M., Rajaure, S. et al.: 10. doi:10.1186/s40623-016-0383-7. hdl:2115/60622. S2CID 41484836.

- ^ "M5.5 – Greater Los Angeles area, California". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2021-11-06.

- ^ Hough, S. E.; Graves, R. W. (22 June 2020). "Nature:The 1933 Long Beach Earthquake (California, USA) Ground Motions and Rupture Scenario". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 10017. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-66299-w. PMC 7308333. PMID 32572047. S2CID 219959257.

Sources

- Allen, T. I.; Wald, D. J.; Hotovec, A. J.; Lin, K.; Earle, P. S.; Marano, K. D. (2008), An atlas of ShakeMaps for selected global earthquakes (PDF), Open-File Report 2008–1236, United States Geological Survey

- Allen, T. I.; Wald, D. J.; Earle, P. S.; Marano, K. D.; Hotovec, A. J.; Lin, K.; Hearne, M. G. (2009), "An atlas of ShakeMaps and population exposure catalog for earthquake loss modeling" (PDF), Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering, 7 (3): 701–718, Bibcode:2009BuEE....7..701A, doi:10.1007/s10518-009-9120-y, S2CID 58893137, archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-05-10, retrieved 2017-09-15