This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (January 2011) |

Shōwa Statism (國家主義, Kokkashugi) is the nationalist ideology associated with the Empire of Japan, particularly during the Shōwa era. It is sometimes also referred to as Emperor-system fascism (天皇制ファシズム, Tennōsei fashizumu),[1][2] Japanese-style fascism (日本型ファシズム, Nihongata fashizumu)[2] or Shōwa nationalism.

Developed over time since the Meiji Restoration, it advocated for ultranationalism, traditionalist conservatism, militarist imperialism and a dirigisme-based economy.

Origins

editWith a more aggressive foreign policy, and victory over China in the First Sino-Japanese War and over Imperial Russia in the Russo-Japanese War, Japan joined the Western imperialist powers. The need for a strong military to secure Japan's new overseas empire was strengthened by a sense that only through a strong military would Japan earn the respect of Western nations, and thus revision of the "unequal treaties" imposed in the 1800s.

The Japanese military viewed itself as "politically clean" in terms of corruption, and criticized political parties under a liberal democracy as self-serving and a threat to national security by their failure to provide adequate military spending or to address pressing social and economic issues. The complicity of the politicians with the zaibatsu corporate monopolies also came under criticism. The military tended to favour dirigisme and other forms of direct state control over industry, rather than free-market capitalism, as well as greater state-sponsored social welfare, to reduce the attraction of socialism and communism in Japan.

The special relation of militarists and the central civil government with the Imperial Family supported the important position of the Emperor as Head of State with political powers and the relationship with the nationalist right-wing movements. However, Japanese political thought had relatively little contact with European political thinking until the 20th century.

Under this ascendancy of the military, the country developed a very hierarchical, aristocratic economic system with significant state involvement. During the Meiji Restoration, there had been a surge in the creation of monopolies. This was in part due to state intervention, as the monopolies served to allow Japan to become a world economic power. The state itself owned some of the monopolies, and others were owned by the zaibatsu. The monopolies managed the central core of the economy, with other aspects being controlled by the government ministry appropriate to the activity, including the National Central Bank and the Imperial family. This economic arrangement was in many ways similar to the later corporatist models of European fascists.

During the same period, certain thinkers with ideals similar to those from shogunate times developed the early basis of Japanese expansionism and Pan-Asianist theories such as the Hakkō ichiu, Yen Block, and Amau doctrines,[3] which eventually served as the basis for policies such as the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.[4]

Developments in the Shōwa era

editInternational policy

editThe 1919 Treaty of Versailles did not recognize the Empire of Japan's territorial claims, and international naval treaties between Western powers and the Empire of Japan (Washington Naval Treaty and London Naval Treaty) imposed limitations on naval shipbuilding which limited the size of the Imperial Japanese Navy at a 10:10:6 ratio. These measures were considered by many in Japan as the refusal by the Occidental powers to consider Japan an equal partner. The latter brought about the May 15 incident.

Based on national security, these events released a surge of Japanese nationalism and ended collaboration diplomacy which supported peaceful economic expansion. The implementation of a military dictatorship and territorial expansionism were considered the best ways to protect the Yamato-damashii.

Civil discourse on statism

editIn the early 1930s, the Ministry of Home Affairs began arresting left-wing political dissidents, generally to extract a confession and renouncement of anti-state leanings. Over 30,000 such arrests were made between 1930 and 1933. In response, a large group of writers founded a Japanese branch of the International Popular Front Against Fascism and published articles in major literary journals warning of the dangers of statism. Their periodical, The People's Library (人民文庫), achieved a circulation of over five thousand and was widely read in literary circles, but was eventually censored, and later dismantled in January 1938.[5]

Proponents

editIkki Kita

editIkki Kita was an early 20th-century political theorist, who advocated a hybrid of statism with "Asian nationalism", which thus blended the early ultranationalist movement with Japanese militarism. His political philosophy was outlined in his thesis Kokutairon and Pure Socialism of 1906 and An Outline Plan for the Reorganization of Japan (日本改造法案大綱 Nihon Kaizō Hōan Taikō) of 1923. Kita proposed a military coup d'état to replace the existing political structure of Japan with a military dictatorship. The new military leadership would rescind the Meiji Constitution, ban political parties, replace the Diet of Japan with an assembly free of corruption, and would nationalize major industries. Kita also envisioned strict limits to private ownership of property, and land reform to improve the lot of tenant farmers. Thus strengthened internally, Japan could then embark on a crusade to free all of Asia from Western imperialism.

Although his works were banned by the government almost immediately after publication, circulation was widespread, and his thesis proved popular not only with the young officer class excited at the prospects of military rule and Japanese expansionism but with the populist movement for its appeal to the agrarian classes as well.

Shūmei Ōkawa

editShūmei Ōkawa was a right-wing political philosopher, active in numerous Japanese nationalist societies in the 1920s. In 1926, he published Japan and the Way of the Japanese (日本及び日本人の道, Nihon oyobi Nihonjin no michi), among other works, which helped popularize the concept of the inevitability of a clash of civilizations between Japan and the west. Politically, his theories built on the works of Ikki Kita, but further emphasized that Japan needed to return to its traditional kokutai traditions to survive the increasing social tensions created by industrialization and foreign cultural influences.

Sadao Araki

editSadao Araki was a noted political philosopher in the Imperial Japanese Army during the 1920s, who had a wide following within the junior officer corps. Although implicated in the February 26 Incident, he went on to serve in numerous influential government posts, and was a cabinet minister under Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe.

The Japanese Army, already trained along Prussian lines since the early Meiji period, often mentioned the affinity between yamato-damashii and the "Prussian Military Spirit" in pushing for a military alliance with Italy and Germany along with the need to combat communism and socialism. Araki's writing is imbued with nostalgia towards the military administrative system of the former shogunate, in a similar manner to which the National Fascist Party of Italy looked back to the ancient ideals of the Roman Empire or the NSDAP in Germany recalled an idealized version of the Holy Roman Empire and the Teutonic Order.

Araki modified the interpretation of the bushido warrior code to seishin kyōiku ("spiritual training"), which he introduced to the military as Army Minister, and the general public as Education Minister, and in general brought the concepts of the Showa Restoration movement into mainstream Japanese politics.

Some of the distinctive features of this policy were also used outside Japan. The puppet states of Manchukuo, Mengjiang, and the Wang Jingwei Government were later organized partly following Araki's ideas. In the case of Wang Jingwei's state, he himself had some German influences—prior to the Japanese invasion of China, he met with German leaders and picked up some fascist ideas during his time in the Kuomintang. These, he combined with Japanese militarist thinking. Japanese agents also supported local and nationalist elements in Southeast asia and White Russian residents in Manchukuo before war broke out.

Seigō Nakano

editSeigō Nakano sought to bring about a rebirth of Japan through a blend of the samurai ethic, Neo-Confucianism, and populist nationalism modelled on European fascism. He saw Saigō Takamori as epitomizing the 'true spirit' of the Meiji ishin, and the task of modern Japan to recapture it.

Shōwa Restoration Movement

editIkki Kita and Shūmei Ōkawa joined forces in 1919 to organize the short-lived Yūzonsha, a political study group intended to become an umbrella organization for the various right-wing statist movements. Although the group soon collapsed due to irreconcilable ideological differences between Kita and Ōkawa, it served its purpose in that it managed to join the right-wing anti-socialist, Pan-Asian militarist societies with centrist and left-wing supporters of a strong state.

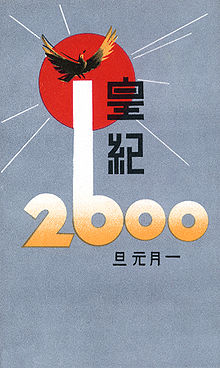

In the 1920s and 1930s, these supporters of Japanese statism used the slogan Showa Restoration (昭和維新, Shōwa isshin), which implied that a new resolution was needed to replace the existing political order dominated by corrupt politicians and industrialists, with one which (in their eyes), would fulfil the original goals of the Meiji Restoration of direct Imperial rule via military proxies.

However, the Shōwa Restoration had different meanings for different groups. For the radicals of the Sakurakai, it meant the violent overthrow of the government to create a national syndicalist state with more equitable distribution of wealth and the removal of corrupt politicians and zaibatsu leaders. For the young officers, it meant a return to some form of "military-shogunate" in which the emperor would re-assume direct political power with dictatorial attributes, as well as divine symbolism, without the intervention of the Diet or liberal democracy, but who would effectively be a figurehead with day-to-day decisions left to the military leadership.

Another point of view was supported by Prince Chichibu, a brother of Emperor Shōwa, who repeatedly counselled him to implement a direct imperial rule, even if that meant suspending the constitution.[6]

In principle, some theorists proposed Shōwa Restoration, the plan of giving direct dictatorial powers to the Emperor (due to his divine attributes) for leading the future overseas actions in mainland Asia. This was the purpose behind the February 26 Incident and other similar uprisings in Japan. Later, however, these previously mentioned thinkers decided to organize their own political clique based on previous radical, militaristic movements in the 1930s; this was the origin of the Kodoha party and their political desire to take direct control of all the political power in the country from the moderate and democratic political voices.

Following the formation of this "political clique", there was a new current of thought among militarists, industrialists and landowners that emphasized a desire to return to the ancient shogunate system, but in the form of a modern military dictatorship with new structures. It was organized with the Japanese Navy and Japanese Army acting as clans under command of a supreme military native dictator (the shōgun) controlling the country. In this government, the Emperor was covertly reduced in his functions and used as a figurehead for political or religious use under the control of the militarists.[citation needed]

The failure of various attempted coups, including the League of Blood Incident, the Imperial Colors Incident and the February 26 Incident, discredited supporters of the Shōwa Restoration movement, but the concepts of Japanese statism migrated to mainstream Japanese politics, where it joined with some elements of European fascism.

Comparisons with European fascism

editEarly Shōwa statism is sometimes given the retrospective label "fascism"[by whom?], but this was not a self-appellation. When authoritarian tools of the state such as the Kempeitai were put into use in the early Shōwa period, they were employed to protect the rule of law under the Meiji Constitution from perceived enemies on both the left and the right.[7]

Some ideologists, such as Kingoro Hashimoto, proposed a single-party dictatorship, based on populism, patterned after the European fascist movements. An Investigation of Global Policy with the Yamato Race as Nucleus shows the influence clearly.[8]

These geopolitical ideals developed into the Amau Doctrine (天羽声明, an Asian Monroe Doctrine), stating that Japan assumed total responsibility for peace in Asia, and can be seen later when Prime Minister Kōki Hirota proclaimed justified Japanese expansion into northern China as the creation of "a special zone, anti-communist, pro-Japanese and pro-Manchukuo" that was a "fundamental part" of Japanese national existence.

Although the reformist right-wing, kakushin uyoku, was interested in the concept, the idealist right-wing, or kannen uyoku, rejected fascism as they rejected all things of western origin. [citation needed]

Because of the mistrust of unions in such unity, the Japanese went to replace them with "councils" (経営財団, keiei zaidan, lit. "management foundations", shortened: 営団 eidan) in every factory, containing both management and worker representatives to contain conflict.[9] This was part of a program to create a classless national unity.[10] However, the nobles had a large amount of control in society in which there was no parallel in fascist countries.. The most famous of the councils is the Teito Rapid Transit Authority (帝都高速度交通営団, Teito Kōsoku-do Kōtsū Eidan, lit. "Imperial Capital Highspeed Transportation Council", TRTA), which survived the dismantling of the councils under the US-led Allied occupation. The TRTA is now the Tokyo Metro.

Kokuhonsha

editThe Kokuhonsha was founded in 1924 by conservative Minister of Justice and President of the House of Peers Hiranuma Kiichirō.[11] It called on Japanese patriots to reject the various foreign political "-isms" (such as socialism, communism, Marxism, anarchism, etc.) in favor of a rather vaguely defined "Japanese national spirit" (kokutai). The name "kokuhon" was selected as an antithesis to the word "minpon", from minpon shugi, the commonly-used translation for the word "democracy", and the society was openly supportive of totalitarian ideology.[12]

Divine Right and Way of the Warrior

editOne particular concept exploited was a decree ascribed to the legendary first emperor of Japan, Emperor Jimmu, in 660 BC: the policy of hakkō ichiu (八紘一宇, all eight corners of the world under one roof).[13]

This also related to the concept of kokutai or national polity, meaning the uniqueness of the Japanese people in having a leader with spiritual origins.[8] The pamphlet Kokutai no Hongi taught that students should put the nation before the self, and that they were part of the state and not separate from it.[14] Shinmin no Michi enjoined all Japanese to follow the central precepts of loyalty and filial piety, which would throw aside selfishness and allow them to complete their "holy task."[15]

The bases of the modern form of kokutai and hakkō ichiu were to develop after 1868 and would take the following form:

- Japan is the centre of the world, with its ruler, the Tennō (Emperor), a divine being, who derives his divinity from ancestral descent from the great Amaterasu-Ōmikami, the Goddess of the Sun herself.

- The Kami (Japan's gods and goddesses) have Japan under their special protection. Thus, the people and soil of Dai Nippon and all its institutions are superior to all others.

- All of these attributes are fundamental to the Kodoshugisha (Imperial Way) and give Japan a divine mission to bring all nations under one roof, so that all humanity can share the advantage of being ruled by the Tenno.

The concept of the divine Emperors was another belief that was to fit the later goals. It was an integral part of the Japanese religious structure that the Tennō was divine, descended directly from the line of Ama-Terasu (or Amaterasu, the Sun Kami or Goddess).

The final idea that was modified in modern times was the concept of Bushido. This was the warrior code and laws of feudal Japan, that while having cultural surface differences, was at its heart not that different from the code of chivalry or any other similar system in other cultures. In later years, the code of Bushido found a resurgence in belief following the Meiji Restoration. At first, this allowed Japan to field what was considered one of the most professional and humane militaries in the world, one respected by friend and foe alike.[citation needed] Eventually, however, this belief would become a combination of propaganda and fanaticism that would lead to the Second Sino-Japanese War of the 1930s and World War II.

It was the third concept, especially, that would chart Japan's course towards several wars that would culminate with World War II.

New Order Movement

editDuring 1940, Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe proclaimed the Shintaisei (New National Structure), making Japan into a "National Defense State". Under the National Mobilization Law, the government was given absolute power over the nation's assets. All political parties were ordered to dissolve into the Imperial Rule Assistance Association, forming a one-party state based on totalitarian values. Such measures as the National Service Draft Ordinance and the National Spiritual Mobilization Movement were intended to mobilize Japanese society for a total war against the West.

Associated with government efforts to create a statist society included creation of the Tonarigumi (residents' committees), and emphasis on the Kokutai no Hongi ("Japan's Fundamentals of National Policy"), presenting a view of Japan's history, and its mission to unite the East and West under the Hakkō ichiu theory in schools as official texts. The official academic text was another book, Shinmin no Michi (The Subject's Way), the "moral national Bible", presented an effective catechism on nation, religion, cultural, social, and ideological topics.

Axis powers

editImperial Japan withdrew from the League of Nations in 1933, bringing it closer to Nazi Germany, which also left that year, and Fascist Italy, which was dissatisfied with the League. During the 1930s Japan drifted further away from Western Europe and the United States. During this period, American, British, and French films were increasingly censored, and in 1937 Japan froze all American assets throughout its empire.[16]

In 1940, the three countries formed the Axis powers, and became more closely linked. Japan imported German propaganda films such as Ohm Krüger (1941), advertising them as narratives showing the suffering caused by Western imperialism.

End of Statism

editStatism in Shōwa Japan was discredited and destroyed by the failure of Japan's military in World War II. After the surrender of Japan, Japan was put under Allied occupation. Some of its former military leaders were tried for war crimes before the Tokyo tribunal, the government educational system was revised, and the tenets of liberal democracy were written into the post-war Constitution of Japan as one of its key themes.

The collapse of statist ideologies in 1945–46 was paralleled by a formalisation of relations between the Shinto religion and the Japanese state, including disestablishment: termination of Shinto's status as a state religion. In August 1945, the term State Shinto (Kokka Shintō) was invented to refer to some aspects of statism. On 1 January 1946, Emperor Shōwa issued an imperial rescript, sometimes referred as the Ningen-sengen ("Humanity Declaration") in which he quoted the Five Charter Oath (Gokajō no Goseimon) of his grandfather, Emperor Meiji and renounced officially "the false conception that the Emperor is a divinity". However, the wording of the Declaration – in the court language of the Imperial family, an archaic Japanese dialect known as Kyūteigo – and content of this statement have been the subject of much debate. For instance, the renunciation did not include the word usually used to impute the Emperor's divinity: arahitogami ("living god"). It instead used the unusual word akitsumikami, which was officially translated as "divinity", but more literally meant "manifestation/incarnation of a kami ("god/spirit")". Hence, commentators such as John W. Dower and Herbert P. Bix have argued, Hirohito did not specifically deny being a "living god" (arahitogami).

See also

editReferences

edit- Beasley, William G. (1991). Japanese Imperialism 1894-1945. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-822168-1.

- Bix, Herbert P. (2001). Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-093130-2.

- Dower, John W. (1986). War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War. Pantheon. ISBN 0-394-50030-X.

- Duus, Peter (2001). The Cambridge History of Japan. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-23915-7.

- Gordon, Andrew (2003). A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511060-9.

- Gow, Ian (2004). Military Intervention in Pre-War Japanese Politics: Admiral Kato Kanji and the Washington System'. RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0-7007-1315-8.

- Hook, Glenn D (2007). Militarization and Demilitarization in Contemporary Japan. Taylor & Francis. ASIN B000OI0VTI.

- Maki, John M (2007). Japanese Militarism, Past and Present. Thompson Press. ISBN 978-1-4067-2272-7.

- Reynolds, E Bruce (2004). Japan in the Fascist Era. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-6338-X.

- Sims, Richard (2001). Japanese Political History Since the Meiji Renovation 1868-2000. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-23915-7.

- Stockwin, JAA (1990). Governing Japan: Divided Politics in a Major Economy. Vintage. ISBN 0-679-72802-3.

- Storry, Richard. "Fascism in Japan: The Army Mutiny of February 1936" History Today (Nov 1956) 6#11 pp 717–726.

- Sunoo, Harold Hwakon (1975). Japanese Militarism, Past and Present. Burnham Inc Pub. ISBN 0-88229-217-X.

- Wolferen, Karen J (1990). The Enigma of Japanese Power;People and Politics in a Stateless Nation. Vintage. ISBN 0-679-72802-3.

- Brij, Tankha (2006). Kita Ikki And the Making of Modern Japan: A Vision of Empire. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 1-901903-99-0.

- Wilson, George M (1969). Radical Nationalist in Japan: Kita Ikki 1883-1937. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-74590-6.

- Was Kita Ikki a Socialist?, Nik Howard, 2004.

- Baskett, Michael (2009). "All Beautiful Fascists?: Axis Film Culture in Imperial Japan" in The Culture of Japanese Fascism, ed. Alan Tansman. Durham: Duke University Press. pp. 212–234. ISBN 0822344521

- Bix, Herbert. (1982) "Rethinking Emperor-System Fascism" Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars. v. 14, pp. 20–32.

- Dore, Ronald, and Tsutomu Ōuchi. (1971) "Rural Origins of Japanese Fascism. " in Dilemmas of Growth in Prewar Japan, ed. James Morley. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 181–210. ISBN 0-691-03074-X

- Duus, Peter and Daniel I. Okimoto. (1979) "Fascism and the History of Prewar Japan: the Failure of a Concept, " Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 65–76.

- Fletcher, William Miles. (1982) The Search for a New Order: Intellectuals and Fascism in Prewar Japan. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-1514-4

- Maruyama, Masao. (1963) "The Ideology and Dynamics of Japanese Fascism" in Thought and Behavior in Modern Japanese Politics, ed. Ivan Morris. Oxford. pp. 25–83.

- McGormack, Gavan. (1982) "Nineteen-Thirties Japan: Fascism?" Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars v. 14 pp. 2–19.

- Morris, Ivan. ed. (1963) Japan 1931-1945: Militarism, Fascism, Japanism? Boston: Heath.

- Tanin, O. and E. Yohan. (1973) Militarism and Fascism in Japan. Westport, Conn. : Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-8371-5478-2

Notes

edit- ^ Kasza, Gregory (2006). Blamires, Cyprian; Jackson, Paul (eds.). World Fascism: A-K. ABC-CLIO. p. 353. ISBN 9781576079409.

- ^ a b Tansman, Alan (2009). The Culture of Japanese Fascism. Duke University Press. p. 5. ISBN 9780822390701.

- ^ Akihiko Takagi, [1] [dead link] mentions "Nippon Chiseigaku Sengen ("A manifesto of Japanese Geopolitics") written in 1940 by Saneshige Komaki, a professor of Kyoto Imperial University and one of the representatives of the Kyoto school, [as] an example of the merging of geopolitics into Japanese traditional ultranationalism."

- ^ James L. McClain, Japan: A Modern History p 470 ISBN 0-393-04156-5

- ^ Torrance, Richard (2009). "The People's Library". In Tansman, Alan (ed.). The culture of Japanese fascism. Durham: Duke University Press. pp. 56, 64–5, 74. ISBN 978-0822344520.

- ^ Herbert Bix, Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, 2001, p.284

- ^ Doak, Kevin (2009). "Fascism Seen and Unseen". In Tansman, Alan (ed.). The culture of Japanese fascism. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0822344520.

Careful attention to the history of the Special Higher Police, and particularly to their use by Prime Minister Tōjō Hideki against his enemies even further to his political right, reveals that extreme rightists, fascists, and practically anyone deemed to pose a threat to the Meiji constitutional order were at risk.

- ^ a b Rhodes, Anthony (1983). Propaganda: The art of persuasion: World War II. Chelsea House Publishers. p. 246. ISBN 9780877544630.

- ^ Andrew Gordon, A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa to the Present, p195-6, ISBN 0-19-511060-9, OCLC 49704795

- ^ Andrew Gordon, A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa to the Present, p196, ISBN 0-19-511060-9, OCLC 49704795

- ^ Bix, Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, page 164

- ^ Reynolds, Japan in the Fascist Era, page 76

- ^ John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p223 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

- ^ W. G. Beasley, The Rise of Modern Japan, p 187 ISBN 0-312-04077-6

- ^ John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p27 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

- ^ Baskett, Michael (2009). "All Beautiful Fascists?: Axis Film Culture in Imperial Japan". In Tansman, Alan (ed.). The Culture of Japanese Fascism. Durham: Duke University Press. pp. 217–8. ISBN 978-0822344520.

External links

edit- About Japanese Nationalist groups, Kempeitai, Kwantung Army, Group 371 and other relationed topics

- The Fascist Next Door? Nishitani Keiji and the Chuokoron Discussions in Perspective, Discussion Paper by Xiaofei Tu in the electronic journal of contemporary japanese studies, 27 July 2006.

- The 'Uyoku Rōnin Dō', Assessing the Lifestyles and Values of Japan's Contemporary Right Wing Radical Activists, Discussion Paper by Daiki Shibuichi in the electronic journal of contemporary japanese studies, 28 November 2007.