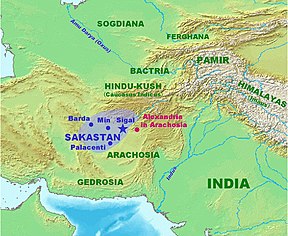

Sistān (Persian: سیستان), also known as Sakastān (Persian: سَكستان "the land of the Saka") and Sijistan (Arabic: سِجِستان), is a historical region in present-day south-western Afghanistan, south-eastern Iran and extending across the borders of south-western Pakistan.[2] Mostly corresponding to the then Achaemenid region of Drangiana and extending southwards of the Helmand River not far off from the city of Alexandria in Arachosia (present day Kandahar).[3][4] Largely desert, the region is bisected by the Helmand River, the largest river in Afghanistan, which empties into the Hamun Lake that forms part of the border between Iran and Afghanistan.

Sijistan

Sistan

Etymology

editSistan derives its name from Sakastan ("the land of the Saka"). The Sakas were a Scythian tribe which migrated to the Iranian Plateau and Indus valley between the 2nd century BC and the 1st century, where they carved a kingdom known as the Indo-Scythian Kingdom.[5][6] In the Bundahishn, a Zoroastrian scripture written in Pahlavi, the province is called "Seyansih".[7] After the Arab conquest of Iran, the province became known as Sijistan/Sistan.[6] The previous Old Persian name of the region, prior to Saka dominance, was zaranka ("waterland"). The older form is also the root of the name Zaranj, capital of the Afghan Nimruz Province.

In the Shahnameh, Sistan is also referred to as Zabulistan, after the region in the eastern part of present-day Afghanistan. In Ferdowsi's epic, Zabulistan is in turn described to be the homeland of the mythological hero Rostam.

History

editEarly history

editIn prehistoric times, the Jiroft Civilization covered parts of Sistan and Kerman Province (possibly as early as the 3rd millennium BC). It is best known from excavations of the archaeological site of Shahr-i Sokhta, a massive third millennium BC city. Other smaller sites have been identified in the region in surveys by American archaeologists Walter Fairservis and George Dales. The site of Nad-i Ali in Afghan Sistan has also been claimed to date from the Bronze Age (Benseval and Francfort 1994).

Earlier the area was occupied by Iranian peoples Eventually a kingdom known as Arachosia was formed, parts of which were ruled by the Medes by 600 BC. The Medes were overthrown by the Achaemenid Empire in 550 BC, and the rest Arachosia was soon annexed. The archaeological site of Dahan-e Gholaman was a major Achaemenid centre. n the 4th century BCE, Alexander the Great annexed the region during his conquest of the Empire and founded the colony of Alexandria in Arachosia. The city of Bost, now part of Lashkargah, was also developed as a Hellenistic centre.[citation needed]

Alexander's empire fragmented after his death, and Arachosia came under the control of the Seleucid Empire, which traded it to the Mauryan dynasty of India in 305 BC. After the fall of the Mauryans, the region fell to their Greco-Bactrian allies in 180 BC, before breaking away and becoming part of the Indo-Greek Kingdom. The Indo-Parthian king Gondophares was the leader of Sakastan around c. 20–10 BCE as it was part of the Indo-Parthian Kingdom which was also called Gedrosia, its Hellenistic name.[citation needed]

After the mid 2nd century BC, much of the Indo-Greek Kingdom was overrun by tribes known as the Indo-Scythians or Saka, from which Sistan (from Sakastan) eventually derived its name.

Around 100 BC, the Indo-Scythians were defeated by Mithridates II of Parthia (r. c. 124–91 BCE) and the region of Sakastan was incorporated into the Parthian Empire.[8] Parthian governors such as Tanlismaidates ruled the land.[9]

The Parthian Empire then briefly lost the region to its Suren vassals around 20 CE. The regions of Sistan, and Punjab were ruled together by the Indo-Parthians.[10] As the Kushan Empire expanded in the mid 1st century AD, the Indo-Parthian lost their Indian dominions and recentered on Turan and Sakastan.[citation needed]

The Kushans were defeated by the Sasanian Empire in the mid-3rd century, first becoming part of a vassal Kushanshah state before being overrun by the Hephthalites in the mid 5th century. Sassanid armies reconquered Sakastan in by 565, but lost the area to the Rashidun Caliphate after the mid 640s.[citation needed]

Sasanian era

editThe province was formed in ca. 240, during the reign of Shapur I, in his effort to centralise the empire; before that, the province was under the rule of the Parthian Suren Kingdom, whose ruler Ardashir Sakanshah became a Sasanian vassal during the reign of Shapur's father Ardashir I (r. 224–242), who also had the ancient city Zrang rebuilt, which became the capital of the province.[11] Shapur's son Narseh was the first to appointed as the governor of province, which he would govern until 271, when the Sasanian prince Hormizd was appointed as the new governor. Later in ca. 281, Hormizd revolted against his cousin Bahram II. During the revolt, the people of Sakastan supported him. Nevertheless, Bahram II managed to suppress the revolt in 283, and appointed his son Bahram III as the governor of the province.[citation needed]

During his early reign, Shapur II (r. 309–379) appointed his brother Shapur Sakanshah as the governor of Sakastan. Peroz I (r. 459–484), during his early reign, put an end to dynastic rule in province by appointing a Karenid as its governor. The reason behind the appointment was to avoid further family conflict in the province, and in order to gain more direct control of the province.[11]

Islamic conquest

editDuring the Muslim conquest of Persia, the last Sasanian king Yazdegerd III fled to Sakastan in the mid-640s, where its governor Aparviz (who was more or less independent), helped him. However, Yazdegerd III quickly ended this support when he demanded tax money that he had failed to pay.[12][13][14]

In 650, Abd-Allah ibn Amir, after having secured his position in Kerman, sent an army under Mujashi ibn Mas'ud to Sakastan. After having crossed the Dasht-i Lut desert, Mujashi ibn Mas'ud arrived to Sakastan. However, he suffered a heavy defeat and was forced to retreat.[15]

One year later, Abd-Allah ibn Amir sent an army under Rabi ibn Ziyad Harithi to Sakastan. After some time, he reached Zaliq, a border town between Kirman and Sakastan, where he forced the dehqan of the town to acknowledge Rashidun authority. He then did the same at the fortress of Karkuya, which had a famous fire temple, which is mentioned in the Tarikh-i Sistan.[14] He then continued to seize more land in the province. He thereafter besieged Zrang, and after a heavy battle outside the city, Aparviz and his men surrendered. When Aparviz went to Rabi to discuss about the conditions of a treaty, he saw that he was using the bodies of two dead soldiers as a chair. This horrified Aparviz, who in order to spare the inhabitants of Sakastan from the Arabs, made peace with them in return for heavy tribute, which included a tribute of 1,000 slave boys bearing 1,000 golden vessels.[14][13] Sakastan was thus under the control of the Rashidun Caliphate.

Caliphate rule

editHowever, only two years later, the people of Zarang rebelled and defeated Rabi ibn Ziyad Harithi's lieutenant and Muslim garrison of the city. Abd-Allah ibn Amir then sent 'Abd al-Rahman ibn Samura to Sistan, where he managed to suppress the rebellion. Furthermore, he also defeated the Zunbils of Zabulistan, seizing Bust and a few cities in Zabulistan.[14]

During the First Fitna (656–661), the people of Zarang rebelled and defeated the Muslim garrison of the city.[13] In 658, Yazdegerd III's son Peroz III reclaimed Sistan and established a kingdom there, known in Chinese sources as the "Persian Area Command".[16] However, in 663, he was forced to leave the region after suffering a defeat to newly established Umayyad Caliphate, who had succeeded the Rashiduns.[16]

Saffarid dynasty

editSistan became a province of the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates. In the 860s, the Saffarid dynasty emerged in Sistan and proceeded to conquer most of the Islamic East, until it was checked by the Samanids in 900. After the Samanids took the province from the Saffarids, it briefly returned to Abbasid control, but in 917 the governor Abu Yazid Khalid made himself independent. He was followed by a series of emirs with brief reigns until 923, when Ahmad ibn Muhammad restored Saffarid rule in Sistan. After his death in 963, Sistan was ruled by his son Khalaf ibn Ahmad until 1002, when Mahmud of Ghazni invaded Sistan, ending the Saffarid dynasty.[citation needed]

A year later in 1003, Sistan revolted. In response, Mahmud brought an army to suppress the revolt. Mahmud's Hindu troops sacked the mosques and churches of Zarang massacring the Muslims and Christians inside.[17][18]

Nasrid dynasty

editIn 1029, Tadj al-Din I Abu l-Fadl Nasr founded the Nasrid dynasty, who were a branch of the Saffarids. They became vassals of the Ghaznavids. The dynasty then became vassals of the Seljuks in 1048, Ghurids in 1162, and the Khwarezmians in 1212. Mongols sacked Sistan in 1222 and Nasrid dynasty was ended by Khwarezmians in 1225. During Ghaznavid times, elaborate Saffarid palaces were built at Lashkari Bazar and Shahr-i Gholghola.[citation needed]

Mihrabanid dynasty and its successors

editIn 1236, Shams al-Din 'Ali ibn Mas'ud founded Mihrabanid dynasty, another branch of Saffarids, as melik of Sistan for Ilkhanate. Mihrabanid contested with Kartids during Mongol rule. Sistan declared independence in 1335 after demise of Ilkhanate. 1383 Tamerlane conquered Sistan and forced Mihrabanids to become vassals. Overlordship of Timurids was ended in 1507 due to Uzbek invasion in 1507. Uzbeks were driven in 1510 and Mihrabanids became vassals of Safavids until 1537 Safavids deposed the dynasty and gained full control of Sistan.[citation needed]

Safavid rule lasted until 1717 except during Uzbek rule between 1524-1528 and 1578-1598 when the Hotaki dynasty conquered it. Nadir Shah reconquered it in 1727. After assassination of Nadir Shah, Sistan went under the rule of Durrani Empire in 1747. Between 1747 and 1872 Sistan was contested by Persia and Afghanistan. The border dispute between Persia and Afghanistan was solved by Sistan Boundary Mission, led by British General Frederick Goldsmid, who agreed to most of Sistan to be in Persia but the Persians won the withdrawal of the right bank of the Helmand. The countries were not satisfied.[citation needed]

The border was defined more precisely with the Second Sistan Boundary Commission (1903-1905) headed by Arthur Mac Mahon, who had a difficult task due to lack of natural boundaries. The part assigned Persia was included in the province of Balochistan (which took the name of Sistan and Baluchistan in 1986) being the capital Zahedan. In Afghanistan it was part of the Sistan province of Farah-Chakansur that was abolished in the administrative reorganization of 1964 to form the province of Nimruz, with capital Zaranj.[citation needed]

Significance for Zoroastrians

editSistan has a very strong connection with Zoroastrianism and during Sassanid times Lake Hamun was one of two pilgrimage sites for followers of that religion. In Zoroastrian tradition, the lake is the keeper of Zoroaster's seed and just before the final renovation of the world, three maidens will enter the lake, each then giving birth to the saoshyans who will be the saviours of mankind at the final renovation of the world.

Archaeology

editThe most famous archaeological sites in Sistan are Shahr-e Sukhteh and the site on Mount Khajeh, a hill rising up as an island in the middle of Lake Hamun.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ UNESCO. Asbads (windmill) of Iran.

- ^ Classen, Albrecht (2010-11-29). Handbook of Medieval Studies: Terms – Methods – Trends. Walter de Gruyter. p. 6. ISBN 978-3-11-021558-8.

- ^ Ghulam Rahman Amiri (2020-11-01). The Helmand Baluch A Native Ethnography of the People of Southwest Afghanistan. Berghahn Books. p. 7. ISBN 9781800730427.

- ^ N. Rüdiger Schmitt. [1]. Encyclopaedia Iranica. Originally Published: December 15, 1995.

- ^ Frye 1984, p. 193.

- ^ a b Bosworth 1997, pp. 681–685.

- ^ Brunner 1983, p. 750.

- ^ Bivar 1983, pp. 40–41, Katouzian 2009, p. 42

- ^ Rezakhani 2017, p. 32.

- ^ Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh; Stewart, Sarah (2010-03-24). The Age of the Parthians. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85773-308-5.

- ^ a b Christensen 1993, p. 229.

- ^ Pourshariati 2008, p. 222.

- ^ a b c Morony 1986, pp. 203–210.

- ^ a b c d Zarrinkub 1975, p. 24.

- ^ Marshak & Negmatov 1996, p. 449.

- ^ a b Daryaee 2009, p. 37.

- ^ C.E. Bosworth, The Ghaznavids 994-1040, (Edinburgh University Press, 1963), 89.

- ^ Prakash, Buddha (1971). Evolution of Heroic Tradition in Ancient Panjab. Punjabi University. p. 147.

Sources

edit- Daryaee, Touraj (2009). Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–240. ISBN 978-0857716668.

- Greatrex, Geoffrey; Lieu, Samuel N. C. (2002). The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars (Part II, 363–630 AD). New York, New York and London, United Kingdom: Routledge (Taylor & Francis). ISBN 0-415-14687-9.

- Pourshariati, Parvaneh (2008). Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire: The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran. London and New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-645-3.

- Zarrinkub, Abd al-Husain (1975). "The Arab conquest of Iran and its aftermath". The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–57. ISBN 978-0-521-20093-6.

- Morony, M. (1986). "ʿARAB ii. Arab conquest of Iran". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 2. pp. 203–210.

- Christensen, Peter (1993). The Decline of Iranshahr: Irrigation and Environments in the History of the Middle East, 500 B.C. to A.D. 1500. Museum Tusculanum Press. pp. 1–351. ISBN 9788772892597.

- Shapur Shahbazi, A. (2005). "SASANIAN DYNASTY". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- Frye, Richard Nelson (1984). The History of Ancient Iran. C.H.Beck. pp. 1–411. ISBN 9783406093975.

The history of ancient iran.

- Schmitt, R. (1995). "DRANGIANA". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 5. pp. 534–537.

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (1997). "Sīstān". The Encyclopedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume IX: San–Sze. Leiden, and New York: BRILL. pp. 681–685. ISBN 9789004082656.

- Gazerani, Saghi (2015). The Sistani Cycle of Epics and Iran's National History: On the Margins of Historiography. BRILL. pp. 1–250. ISBN 9789004282964.

- Bosworth, C. E. (2011). "SISTĀN ii. In the Islamic period". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Barthold, W. (1986). "ʿAmr b. al-Layth". The Encyclopedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume I: A–B. Leiden and New York: BRILL. pp. 452–453. ISBN 90-04-08114-3.

- Bosworth, C.E. (1975). "The Ṭāhirids and Ṣaffārids". In Frye, R.N. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 90–135. ISBN 9780521200936.

- Bosworth, C. E. (1975). "The rise of the new Persian language". In Frye, R. N. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 595–633. ISBN 0-521-20093-8.

- Benseval, R. and H.-P. Francfort (1994), “The Nad-i Ali ‘Surkh Dagh’: A Bronze Age Monumental Platform in Central Asia.” In From Sumer to Meluhha: Contributions to the Archaeology of South and West Asia in Memory of George F. Dales, Jr. Ed. J.M. Kenoyer. (Madison: Wisconsin Archaeological Reports 4)

- Bivar, A.D.H. (1983). "The Political History of Iran Under the Arsacids". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 3(1): The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 21–99. ISBN 0-521-20092-X..

- Katouzian, Homa (2009), The Persians: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Iran, New Haven & London: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-12118-6.

- Marshak, B.I.; Negmatov, N.N. (1996). "Sogdiana". In B.A. Litvinsky, Zhang Guang-da and R. Shabani Samghabadi (ed.). History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volume III: The Crossroads of Civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750. UNESCO. ISBN 92-3-103211-9.

- Brunner, Christopher (1983). "Geographical and Administrative divisions: Settlements and Economy". The Cambridge History of Iran: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian periods (2). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 747–778. ISBN 978-0-521-24693-4.

Further reading

edit- Gnoli, Gherardo (1967). Ricerche storiche sul Sīstān antico [Historical research on the ancient Sīstān]. Centro Studi e Scavi Archeologici in Asia Roma: Reports and memoirs (in Italian). ISBN 978-88-6323-123-6.