A secondary chord is an analytical label for a specific harmonic device that is prevalent in the tonal idiom of Western music beginning in the common practice period: the use of diatonic functions for tonicization.

Secondary chords are a type of altered or borrowed chord, chords that are not part of the music piece's key. They are the most common sort of altered chord in tonal music.[2] Secondary chords are referred to by the function they have and the key or chord in which they function. Conventionally, they are written with the notation "function/key". Thus, one of the most common secondary chords, the dominant of the dominant, is written "V/V" and read as "five of five" or "the dominant of the dominant". The major or minor triad on any diatonic scale degree may have any secondary function applied to it; secondary functions may even be applied to diminished triads in some special circumstances.

Secondary chords were not used until the Baroque period and are found more frequently and freely in the Classical period, even more so in the Romantic period. Composers began to use them less frequently with the breakdown of conventional harmony in modern classical music—but secondary dominants are a cornerstone of popular music and jazz in the 20th century.[3]

Secondary dominant

editA secondary dominant (also applied dominant, artificial dominant, or borrowed dominant) is a major triad or dominant seventh chord built and set to resolve to a scale degree other than the tonic. The dominant (seventh) of the dominant (written as V7/V or V7 of V) is the most frequently encountered.[5] The chord that the secondary dominant is the dominant of is said to be a temporarily tonicized chord. The secondary dominant is normally, though not always, followed by the tonicized chord. Tonicizations that last longer than a phrase are generally regarded as modulations to a new key (or new tonic).

According to music theorists David Beach and Ryan C. McClelland, "[t]he purpose of the secondary dominant is to place emphasis on a chord within the diatonic progression."[6] The secondary-dominant terminology is still usually applied even if the chord resolution is nonfunctional. For example, the V/ii label is still used even if the V/ii chord is not followed by ii.[7]

Definition

editThe major scale contains seven basic chords, which are named with Roman numeral analysis in ascending order. Because tonic triads are either major or minor, one would not expect to find diminished chords (either the viio in major or the iio in minor) tonicized by a secondary dominant.[2] It would also not make sense for the tonic of the key itself to be tonicized.

In the key of C major, the five remaining chords are:

Of these chords, the V chord (G major) is said to be the dominant of C major. However, each of the chords from ii to vi also has its own dominant. For example, V (G major) has a D major triad as its dominant. These extra dominant chords are not part of the key of C major as such because they include notes that are not part of the C major scale. Instead, they are secondary dominants.

The notation below shows the secondary-dominant chords for C major. Each chord is accompanied by its standard number in harmonic notation. In this notation, a secondary dominant is usually labeled with the formula "V of ..." (dominant chord of); thus "V of ii" stands for the dominant of the ii chord, "V of iii" for the dominant of iii, and so on. A shorter notation, used below, is "V/ii", "V/iii", etc.

Like most chords, secondary dominants may be seventh chords or chords with other upper extensions.[a] Dominant seventh chords are commonly used as secondary dominants. The notation below shows the same secondary dominants as above but with dominant seventh chords.

Note that the triad V/IV is the same as the I triad. When a seventh is added (V7/IV), it becomes an altered chord because the seventh is not a diatonic pitch. Beethoven's Symphony No. 1 begins with a V7/IV chord:[8]

According to the principles exposed above, in fact, V7/IV, which means the C7 chord, i.e. the dominant seventh chord on the F major scale (C–E–G–B♭), does not represent the tonic because it contains a B♭, which isn't included in the main key, as Beethoven's Symphony No. 1 is written in the key of C major. The chord then resolves on the natural IV (F major) and in the following bar the V7, i.e. G7 (dominant seventh chord on the C major key), is presented.

Chromatic mediants, for example VI is also a secondary dominant of ii (V/ii) and III is V/vi, are distinguished from secondary dominants with context and analysis revealing the distinction.[9]

History

editBefore the 20th century, in the music of J.S. Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, and Brahms, a secondary dominant, along with its chord of resolution, was considered a modulation.[citation needed] Since this was a rather self-contradictory description, theorists in the early 1900s, such as Hugo Riemann (who used the term "Zwischendominante"—"intermediary dominant", still the usual German term for a secondary dominant), searched for a better description of the phenomenon.[citation needed]

Walter Piston first used the analysis "V7 of IV" in a monograph entitled Principles of Harmonic Analysis.[11][b] In his 1941 book Harmony, Piston used the term "secondary dominant".[12] At around the same time (1946–48), Arnold Schoenberg created the expression "artificial dominant" to describe the same phenomenon, in his posthumously published book Structural Functions of Harmony.[13]

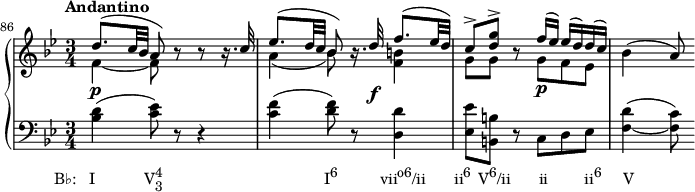

In the fifth edition of Walter Piston's Harmony, a passage from the last movement of Mozart's Piano Sonata K. 283 in G major serves as one illustration of secondary dominants.[14] This passage has three secondary dominants. The final four chords form a circle of fifths progression, ending in a standard dominant-tonic cadence, which concludes the phrase.

In jazz and popular music

editIn jazz harmony, a secondary dominant is any dominant seventh chord on a weak beat[citation needed] and resolves downward by a perfect fifth. Thus, a chord is a secondary dominant when it functions as the dominant of some harmonic element other than the key's tonic and resolves to that element. This is slightly different from the traditional use of the term, where a secondary dominant does not have to be a seventh chord, occur on a weak beat, or resolve downward. If a non-diatonic dominant chord is used on a strong beat, it is considered an extended dominant. If it doesn't resolve downward, it may be a borrowed chord.[citation needed]

Secondary dominants are used in jazz harmony in the bebop blues and other blues progression variations, as are substitute dominants and turnarounds.[15] In some jazz tunes, all or almost all of the chords that are used are dominant chords. For example, in the standard jazz chord progression ii–V–I, which would normally be Dm–G7–C in the key of C major, some tunes will use D7–G7–C7. Since jazz tunes are often based on the circle of fifths, this creates long sequences of secondary dominants.[citation needed]

Secondary dominants are also used in popular music. Examples include II7 (V7/V) in Bob Dylan's "Don't Think Twice, It's All Right" and III7 (V7/vi) in Betty Everett's "The Shoop Shoop Song (It's in His Kiss)".[17] "Five Foot Two, Eyes of Blue" features chains of secondary dominants.[18] "Sweet Georgia Brown" opens with V/V/V–V/V–V–I.

Extended dominant

editAn extended dominant chord is a secondary dominant seventh chord that resolves down by a fifth to another dominant seventh chord. A series of extended dominant chords continues to resolve downwards by the circle of fifths until it reaches the tonic chord. The most common extended dominant chord is the tertiary dominant,[citation needed] which resolves to a secondary dominant. For example, V/V/V (in C major, A(7)) resolves to V/V (D(7)), which resolves to V (G(7)), which resolves to I. Note that V/V/V is the same chord as V/ii, but differs in its resolution to a major dominant rather than a minor chord.

Quaternary dominants are rarer, but an example is the bridge section of the rhythm changes, which starts from V/V/V/V (in C major, E(7)). The example below from Chopin's Polonaises, Op. 26, No. 1 (1835)[20] has a quaternary dominant in the second beat (V/ii = V/V/V, V/vi = V/V/V/V).

Secondary leading-tone

editIn music theory, a secondary leading-tone chord is a secondary chord that is rooted on a tone that is a leading-tone of (in short, has a strong affinity to resolve to) a tone just 1 semitone from that root (typically 1 semitone above, though can be below).[22] Like the secondary dominant it can be used as tonicization of only one subsequent chord (which will be rooted in the resolution tone), or the music can continue with other chords/notes in the key of that chord's root for a phrase, or even longer to be considered a modulation to that key. This one-semitone-apart resolution of the secondary leading-tone is in contrast to the secondary dominant which resolves through a wider distance of perfect fifth below or perfect fourth above the chord's root (as per the two distances between dominant and tonic).

While the root of a secondary leading-tone chord needs to be the leading-tone, the other notes may vary and form with it one of: the triad[23] or one of the diminished sevenths (as in seventh scale degree[23] or leading-tone, not necessarily seventh chord) where the type of the diminished seventh is typically related to the type of tonicized triad:

- If the tonicized triad is minor, the leading-tone chord is fully diminished seventh chord.

- If it is major, the leading-tone chord may be either half-diminished or fully diminished, though fully diminished chords are used more often.[24]

Because of their symmetry, secondary leading-tone diminished seventh chords are also useful for modulation; all four notes may be considered the root of any diminished seventh chord. They may resolve to these major or minor diatonic triads:[22]

- In major keys: ii, iii, IV, V, vi

- In minor keys: III, iv, V, VI

Especially in four-part writing, the seventh should resolve downwards by step and if possible the lower tritone should resolve appropriately, inwards if a diminished fifth and outwards if an augmented fourth,[25] as the example below[26] shows.

Secondary leading-tone chords were not used until the Baroque period and are found more frequently and less conventionally in the Classical period. They are found even more frequently and freely in the Romantic period, but they began to be used less frequently with the breakdown of conventional harmony.

The chord progression viio7/V–V–I is quite common in ragtime music.[22]

Secondary supertonic

editThe secondary supertonic chord, or secondary second, is a secondary chord that is on the supertonic scale degree. Rather than tonicizing a degree other than the tonic, as does a secondary dominant, it creates a temporary dominant.[23] Examples include ii7/III (F♯min.7, in C major), ii7/II (Amin.7, in F major), ii7/V (Emin.7, in G major), and ii7/IV (Bmin.7, in E major).[27]

Secondary subdominant

editThe secondary subdominant is the subdominant (IV) of the tonicized chord. For example, in G major, the supertonic chord is A minor and the IV of ii chord is D major.

Others

editThe other secondary functions are the secondary mediant, the secondary submediant, and the secondary subtonic.

See also

edit- Barbershop seventh chord – A major triad plus the harmonic seventh interval

- Backdoor progression – Jazz chord progression

- Circle progression – Type of chord progression

- Common-tone diminished seventh chord – Musical chord

- ii–V–I progression – Common chord progression

- Secondary development

- Subtonic – the lowered or minor seventh degree of the scale, a whole step below the tonic and a half step below the leading

Notes

edit- ^ For example, Ottman 1992, p. 308 discusses secondary dominant ninth chords, such as V9/V.

- ^ Notably, Piston's analytical symbol always used the word "of"—e.g. "V7 of IV" rather than the virgule V7/IV.

References

edit- ^ Benward & Saker 2003, p. 275.

- ^ a b Kostka & Payne 2004, p. 246.

- ^ Benward & Saker 2003, pp. 273–277.

- ^ Benward & Saker 2003, p. 269.

- ^ Kostka & Payne 2004, p. 250.

- ^ Beach & McClelland 2012, p. 32.

- ^ Rawlins & Bahha 2005, p. 59.

- ^ White 1976, p. 5.

- ^ Benward & Saker 2003, pp. 201–204.

- ^ Benward & Saker 2003, p. 274.

- ^ Piston 1933.

- ^ Piston 1941, p. 151: "These temporary dominant chords have been referred to by theorists as attendant chords, parenthesis chords, borrowed chords, etc. We shall call them secondary dominants, in the belief that the term is slightly more descriptive of their function."

- ^ Schoenberg 1954, pp. 15–29, 197. The term "artificial", however, appears to refer to the alteration by which a chord changes into another: "By substituting for [altering] the third in minor triads, they produce 'artificial' major triads and 'artificial' dominant seventh chords. Substituting for [altering] the fifth changes minor triads to 'artificial' diminished triads, commonly used with an added seventh, and changes major triads to augmented. Artificial dominants, artificial dominant seventh chords, and artificial diminished seventh chords are normally used in progressions according to the models V–I, V—VI and V—IV. (p. 16.)

- ^ Piston 1987, p. 257.

- ^ a b Spitzer 2001, p. 62.

- ^ Benward & Saker 2003, p. 277.

- ^ Everett 2009, p. 198. Everett notates major-minor sevenths Xm7.

- ^ Shepherd 2003, p. 10.

- ^ Boyd 1997, p. 43.

- ^ a b Benward & Saker 2003, p. 276.

- ^ Lawn & Hellmer 1996, pp. 97–98.

- ^ a b c Benward & Saker 2003, p. 271.

- ^ a b c Blatter 2007, pp. 132–133.

- ^ Kostka & Payne 2004, p. 263.

- ^ Benward & Saker 2003, p. 272.

- ^ Benward & Saker 2003, p. 270.

- ^ Russo 2015, p. 80.

Bibliography

edit- Beach, David; McClelland, Ryan C. (2012). Analysis of 18th- and 19th-century Musical Works in the Classical Tradition. Routledge. ISBN 9780415806657.

- Benward, Bruce; Saker, Marilyn Nadine (2003). Music: In Theory and Practice. Vol. I (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

- Blatter, Alfred (2007). Revisiting Music Theory: A Guide to the Practice. ISBN 0-415-97440-2.

- Boyd, Bill (1997). Jazz Chord Progressions. ISBN 0-7935-7038-7.

- Everett, Walter (2009). The Foundations of Rock. ISBN 978-0-19-531023-8.

- Kostka, Stefan; Payne, Dorothy (2004). Tonal Harmony (5th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0072852607. OCLC 51613969.

- Ottman, Robert W. (1992) [1961]. Advanced Harmony: Theory and Practice (4th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-006016-X.

- Piston, Walter (1933). Principles of Harmonic Analysis. Boston: E. C. Schirmer. [ISBN unspecified]

- Piston, Walter (1941). Harmony. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. [ISBN unspecified]

- Piston, Walter (1987) [First published 1941]. Harmony. Revised and expanded by Mark Devoto (5th ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-393-95480-7.

- Rawlins, Robert; Bahha, Nor Eddine (2005). Jazzology: The Encyclopedia of Jazz Theory for All Musicians. ISBN 0-634-08678-2.

- Lawn, Richard; Hellmer, Jeffrey L. (1996). Jazz: Theory and Practice. ISBN 978-0-88284-722-1.

- Russo, William (2015) [1961]. Composing for the Jazz Orchestra. University of Chicago. ISBN 978-0-226-73209-1.

- Schoenberg, Arnold (1954). Searle, Humphrey (ed.). Structural Functions of Harmony. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

- Shepherd, John (2003). Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World. Vol. II: Performance and Production. A&C Black. ISBN 9780826463227.

- Spitzer, Peter (2001). Jazz Theory Handbook. ISBN 0-7866-5328-0.

- White, John D. (1976). The Analysis of Music. ISBN 0-13-033233-X.

Further reading

edit- Nettles, Barrie & Graf, Richard (1997). The Chord Scale Theory and Jazz Harmony. Advance Music, ISBN 3-89221-056-X

- Thompson, David M. (1980). A History of Harmonic Theory in the United States. Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press.