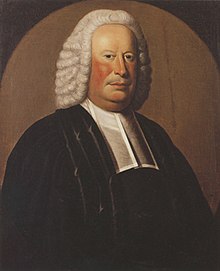

Samuel Johnson (October 14, 1696 – January 6, 1772) was a clergyman, educator, linguist, encyclopedist, historian, and philosopher in colonial America. He was a major proponent of both Anglicanism and the philosophies of William Wollaston and George Berkeley in the colonies, founded and served as the first president of the Anglican King's College, which was renamed Columbia University following the American Revolutionary War, and was a key figure of the American Enlightenment.

Samuel Johnson | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1st President of King's College | |

| In office 1754–1763 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Myles Cooper |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 14, 1696 Guilford, Connecticut Colony, British America |

| Died | January 6, 1772 (aged 75) Stratford, Connecticut Colony, British America |

| Spouses | Charity Floyd Nicoll

(m. 1725; died 1758)Sarah Beach

(m. 1761; died 1763) |

| Children | William Samuel Johnson William "Billy" Johnson |

| Parent | Samuel Johnson Sr. |

| Alma mater | Yale College |

Early life and education

editJohnson was born in Guilford, Connecticut in what was then the colonial-era Colony of Connecticut, the son of a fulling miller, Samuel Johnson Sr., and great-grandson of Robert Johnson, a founder of New Haven Colony, Connecticut. Johnson was substantially influenced by his grandfather, William Johnson, a state assemblyman, village clerk, grammar school teacher, mapmaker, militia leader, judge, and church deacon.[1] His grandfather taught him English at age four, and Hebrew at five; he took young Samuel Johnson around the town on visits to his friends, and proudly had the young boy recite great passages of memorized scripture.[2]

After studying Latin with local ministers and schoolmasters, including Jared Eliot, in Guilford, Clinton and Middleton, Johnson left Guilford at age 13 to attend the Collegiate School at Saybrook, later renamed Yale College, in 1710, where he studied the Reformation logic of Petrus Ramus and the orthodox Puritan theology of Johannes Wolleb (Wollebius) and William Ames. He graduated in 1714 as class valedictorian with a bachelor's degree; three years later, in 1717, he was awarded a master's degree.

Career

editTeacher and author

editJohnson began teaching grammar school in Guilford, Connecticut in 1713, and continued to teach while a student a Yale and for the rest of his life, spending nearly 60 years as a teacher.

In 1714, he began to write a short work titled Synopsis Philosophiae Naturalis, summing up what Puritans knew of natural philosophy.[3] He left this work unfinished and began working instead for his master's thesis by writing in Latin a more ambitious "encyclopedia of all knowledge", titled Technologia Sive Technometria or Ars Encyclopaidia, Manualis Ceu Philosophia; Systema Liber Artis.[4] It was a systematic exploration of all knowledge available to Johnson based on the methods of the Reformation logician Petrus Ramus.

His work on this logical exploration of the Puritan New England Mind eventually resulted in 1271 hierarchically arranged theses. It has been called by Norman Fiering "the best surviving American example of student application of Ramist method to the whole body of human knowledge".[5]

His work on the Encyclopaidia was interrupted when a donation of 800 books collected by Colonial Agent Jeremiah Dummer was sent to Yale late in 1714. He discovered Francis Bacon's Advancement of Learning, the works of John Locke and Isaac Newton and other Age of Enlightenment authors not known to the tutors and graduates of Puritan Yale and Harvard.

Johnson wrote in his Autobiography, “All this was like a flood of day to his low state of mind”, and that “he found himself like one at once emerging out of the glimmer of twilight into the full sunshine of open day".[6] Though he finished his Latin Ramist thesis, he now considered what he had learned at Yale “nothing but the scholastic cobwebs of a few little English and Dutch systems that would hardly now be taken up in the street.”[7]

He used what he learned in the next two years to write in English a Revised Encyclopedia of Philosophy (1716). It was prefixed by a hierarchical Table or map of the intellectual world outlining the sum of all knowledge. It would be the first of a series of tables categorizing "the sum of knowledge" into ever more complex tables used for both categorizing knowledge for libraries and to define curriculum in schools. If he had published the work, it would have predated the first comprehensive English-language encyclopedia,[8] Ephraim Chambers's 1728 Cyclopaedia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, by twelve years.

Yale College

editIn 1716, Johnson was appointed the senior tutor at Yale College. Founded in 1701, Yale was located on a small neck of land in Saybrook, Connecticut. By 1716, Saybrook Point was considered too small to handle the needs of the growing school. Connecticut Governor Gurdon Saltonstall and seven Yale trustees proposed moving the college to New Haven, Connecticut. They were opposed by three trustees, two of whom split the college, and opened a schismatic branch in Wethersfield, Connecticut, taking half the students and the junior Yale tutor with them.

For over two years, Johnson was the sole member of the Yale faculty and the only administrator on-site at the college in New Haven. Unsupervised, he took the opportunity to introduce the Enlightenment into Yale.[9] When Johnson's close friend Daniel Brown left his position as Rector of Hopkin's Grammar School and was formally hired as a second tutor in 1718,[10] Johnson found time to create the first catalog of books of Yale's expanded library, and, between 1717 and 1719, to write up Historical Remarks Concerning the Collegiate School, the first history of Yale.[11]

Johnson's first publication was a broadside printed for the 1718 Yale Commencement,[12] which contained Latin commencement thesis. It shows that Johnson taught Locke, Newton, Copernican astronomy, modern medicine and biology, and, for the first time in an American college, algebra.[13]

The next year was one of tumult. In November 1718, Governor Saltonstall forced the schismatic Wethersfield students, including a young Jonathan Edwards, to come to New Haven. The Wethersfield students were surly and rebellious. Johnson attempted to teach them his Enlightenment curriculum, and the schismatic students complained that he was a poor teacher. They returned to Wethersfield in January, 1719. After the spring 1719 elections confirmed Saltonstall as Governor, the schismatic trustees and students gave up and returned to New Haven.

According to historian Joseph Ellis, "Johnson's presence precluded its reunification,"[14] so he was "sacrificed for college unity"[15] and lost his job as tutor. Out of a job, he designed a new curriculum for a Yale now run by his friend Rector Timothy Cutler and Tutor Daniel Brown, studied religion and philosophy, and wrote up a book on Logic (1720), which may have been used as class notes at Yale, but was not published in his lifetime.[16]

Congregationalist minister

editIn 1720, Johnson became Congregationalist minister of a church in West Haven, Connecticut. Even though "he had much better offers", he took up the position for the sake "of being near the college and library".[17] There he, Yale Rector Timothy Cutler, Yale Tutor Daniel Brown, and six other Connecticut ministers, including the Rev. Jared Eliot of Clinton, and Johnson's friend the Rev. James Wetmore of North Haven, formed a group to study the Anglican divines and the "doctrines and facts of the primitive church". Their reading and discussions led them to question the validity of their ordinations, and the book group members converted from embracing a Presbyterian polity on ordination to an Episcopal one sometime in 1722.

At Yale's September 13, 1722 commencement, in a very public and dramatic event labeled the “Great Apostasy”[18] by American religion historian Sidney Ahlstrom, the nine member group declared for the episcopacy. After strong pressure from the Governor and their family and friends, five of the nine recanted, but Johnson, Cutler, Brown and Wetmore, refused to change their decision, and were expelled from their positions at Yale and their Congregational ministries.

Johnson along with the others left the colony in order to seek ordination in the Church of England. As one of the now famous Great Apostates, he was greeted warmly by the Church and University establishment. On Sunday, March 31, 1723, at the church of St Martin-in-the-Fields, "at the continued appointment and desire of William, Lord Archbishop of Canterbury, and John, Lord Bishop of London, we were ordained Priests most gravely by the Right Reverend Thomas, Lord Bishop of Norwich".[19] He was granted honorary master's degrees at both the University of Oxford, where he was the first American awarded an honorary master's degree by the university, and the University of Cambridge.[20]

He returned to Connecticut in 1723, under the auspices of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, as a missionary priest. He opened the first Anglican church built in the colony, Christ Church in Stratford, Connecticut in 1724.

Charged with spreading the Anglican church in the colony, he formed parishes and opened house churches throughout the colony, which he then staffed with his disciples, then built physical churches in the town. He founded 25 churches in the Colony by 1752,[21] for which he has been called "The Father of the Episcopal Church in Connecticut".[22] Beginning in the 1730s, he participated in a long running pamphlet war with New England Puritans. "Johnson willingly and enthusiastically defended his beliefs in a series of three pamphlets"[23] titled Letters to His Dissenting Parishioners (1733–37), and in the next decade, was attacked, and then counter-attacked his greatest Puritan antagonist, the President of Princeton Jonathan Dickinson, in a series of pamphlets titled Aristocles to Authades (1745–57).

The debate was not only theological, but political and legal. As a minority Anglican in a Congregationalist established church state, he led the Anglican side against both the Old Light and New Light Puritans who dominated the elected Connecticut Assembly, struggling to emancipate his people from Puritan church taxes and laws restricting Anglican worship. He defended his American Anglican practices vigorously, and advocated for an Anglican Bishop in America. This request for a Bishop was vigorously opposed not only by New England Puritans and their supporters in England, but by Southern Anglicans who wished to preserve their independence. Johnson failed in this effort: no Church of England Bishop was ever sent to America, and there was no Episcopal Bishop until Samuel Seabury (bishop) was ordained by the Scottish Episcopal Church. In addition to dealing with the powerful Old Lights from 1723 on, after 1740 he now had to deal with the evangelical outburst occasioned by the New Light popular preacher and fellow Anglican minister George Whitefield and the Great Awakening he unleashed.

He opened a successful common school in Stratford shortly after his arrival in 1723, and boarded and tutored the sons of prominent New York families to prepare them for college.[24] He also trained Yale students for the Anglican ministry at his parsonage in Stratford, converting many of them from Puritan denominations, as well as training Anglicans in a kind of small seminary. Between 1724 and his death in 1772, Johnson mentored 63 Yale graduates who intended to take Anglican orders. His disciples resided in all 13 states and Canada by the time of the Revolution.[25]

Creating "A New System of Morality"

editJohnson was a seminal figure of American philosophy. Though busy with ministry and educational duties, and raising his family, he never stopped learning or writing, and kept to his self-appointed mission to write up the sum of all knowledge. In February 1729, Johnson noted in his Autobiography, "came that very extraordinary genius Bishop Berkeley, then Dean of Derry, into America, and resided two years and a half at Rhode Island". Johnson hurried to visit him, and his group in Rhode Island, including the painter John Smybert. He became for a time a disciple of Berkeley's, and exchanged many letters with the philosopher over the years,[26] discussing Berkeley's idealist philosophy. Before Berkeley left America in September 1731, Johnson convinced Berkeley to donate to Yale a large number of books, 500 pounds sterling, and a 100-acre farm with 100 pound sterling yearly income which would fund three scholars at the college.[27]

Johnson published the essay "An Introduction to the Study of Philosophy, exhibiting a General view of all the Arts and Sciences” in the May 1731 issue of London-based periodical The Present State of the Republick of Letters (1728–36). Written just as he was about to send his two Nicoll stepsons to Yale, it was a manual for teaching young men ethics and moral philosophy, things not taught at a Yale that had reverted to the Puritan curriculum after the Great Apostasy; it was the first work published by an American in a British journal.[28]

In 1740s, while Johnson's son William Samuel Johnson was attending Yale, Johnson collaborated with Rector Thomas Clap to create a new curriculum, for which he revised his moral philosophy and his tables on the sum of all knowledge. He published it as a textbook titled An Introduction to the Study of Philosophy (1743). It was three times longer than his previous essay. In large bold letters on the front page facing the title page, he proclaimed it "A New System of Morality".[29] The work "was intended from the beginning to accompany President Clap of Yale's 1743 Library Catalogue of the Library of the Yale–College in New Haven."[30]

The work contains a moral philosophy textbook along with a revision of his table of the sum of all knowledge, which was used by Clap to index his library catalog, and by Johnson to order a recommended reading[31] list of books to be read by Yale students included as an appendix to the textbook.[32] Though Johnson had begun replacing the Puritans' ideas of Predestination and Sin with his American Enlightenment idea of pursuing happiness as far back as his sermons in 1715,[33] the new system makes the pursuit of happiness its starting point. In its opening paragraph, reflecting the influence of William Wollaston and Berkeley, he defines philosophy as "The Pursuit of true Happiness in the Knowledge of things as being what they really are, and in acting or practicing according to that Knowledge."[34] Going beyond Wollaston and Berkeley, "Johnson extended these men's constructions with his own unique practice-oriented ideas of perception leading to action, and a freewill model of humans with a value system focused on pursuing happiness."[35]

Its library catalog schema taken from Johnson's scheme was adopted by other colleges, and "was superior to anything until Melvil Dewey published his Dewey Decimal Classification Scheme in 1876."[36] Johnson, who had first cataloged the Yale library back in 1719 when its books were moved from Saybrook to New Haven, and who had secured the large Berkeley donation of books, selecting which volumes would go to Yale from the wealthy philosopher's large collection, has been called “The Father of American Library Classification”.[37]

Also in 1743, for his successful missionary work and his defense of the Anglican church in America he received an honorary doctorate of divinity from Oxford. He was only the third American to receive this honor.[38] That same year he built the second Christ Church in Stratford, startling his Puritan neighbors with Gothic-style architectural elements, heating, an organ, and a steeple with a clock and a bell, topped by a gold-brass rooster.

Johnson revised his moral philosophy textbook again, titling it Ethices Elementa: or the First Principles of Moral Philosophy. According to educator Henry Barnard, “This work had a high reputation at the time of its publication, and met with an extensive sales.”[39] He revised it again with editions released in 1752 in Philadelphia and 1754 in London. Professor Mark Garett Longaker noted that it contained "a system of morals built upon his philosophical idealism, and the conclusion of this entire system (moral, philosophical, and rhetorical) is that all human endeavor aims towards happiness, a condition realized when one fully understands and obeys God's will."[40]

King's College in New York City

editJohnson had been considering a college in New York since 1749.[41] In 1750, Johnson began to exchange a series of letters with Benjamin Franklin over the founding of a "new-model" or "English" college. Franklin admired Johnson's moral philosophy, and asked him to head up a proposed College of Philadelphia.[42] Johnson declined the offer, and instead worked with his wife's relations, his step-sons, former students, and the rector and vestrymen of the Anglican Trinity Church in New York City to found a college there.

In 1751, a board of trustees had been appointed by the New York colonial assembly to manage money raised in a lottery for a college in New York City. In 1752, Johnson was proposed as the logical choice for its president.[43] They decided to name it King's College to help them secure an official royal charter from King George II. Johnson had recently met William Smith, a young Scot immigrant tutor, at the New York City salon of Mrs. De Lancey, wife of Lt. Governor James De Lancey. Johnson had suggested and mentored Smith's writing of a Utopian book of college education, titled A General Idea of the College of Mirania (1753). Johnson recommenced the young William Smith to Franklin.

During the colonial era, "The chair of moral philosophy stood above all other faculty positions in importance and prestige."[44] Selecting a moral philosophy was thus a fundamentally important consideration when founding a college. In 1752, at Franklin's urging, Johnson revised his philosophy textbook again to create a philosophy suitable for the proposed new-model colleges. Franklin took the unusual step (for him) of self-funding the domestic printing of Elementa Philosophica (1752).

New American college model

editAlong with Benjamin Franklin and William Smith, Johnson created what President James Madison of the College of William and Mary called a new-model[45] plan or style of American college. They decided it would be profession-oriented, with classes taught in English instead of Latin, have subject matter experts as professors instead of one tutor leading a class for four years, and there would be no religious test for admission.[46] They also replaced the study of theology with non-denominational moral philosophy, using Johnson's "new system of morality" and his philosophy textbook as the core of the curriculum.

Johnson, Franklin, and Smith met in Stratford in June 1753. They planned two new-model colleges: Johnson would open King's College in New York City, and Franklin and Smith would open the College of Philadelphia, now the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Immediately after the meeting, Smith left for London to raise funds and receive Anglican orders. Franklin and the board of trustees appointed him Provost of the College of Philadelphia when he returned. Johnson with the help of his stepson Benjamin Nicoll, his former students. who were now powerful merchants, the De Launcey-Nicoll Popular downstate majority party in the New York Assembly, and the clergy and vestry of Trinity Church, New York City, created a board of Governors for the new college, ensuring that it had an Anglican majority though it included Dutch Reformed Church and Presbyterian Church members. The assembly voted that a lottery be established to raise funds for the new college.

The funding was bitterly opposed in print by board member William Livingston and other Presbyterian politicians along with their Provincial upstate party allies in an intense two year newspaper war. Without funding and without an official charter, Johnson defiantly opened King's College (now Columbia University) in July 1754. On October 31, it finally received the Royal charter. Its charter promoted a college without a religious test for admission, was practice and profession oriented, public spirited, inclusive and diverse, and taught the then new disciplines of English literature and moral philosophy. It was polytechnic in scope, teaching math, science, history, commerce, government, and nature. Colonial historian Richard Gummere noted that, "Had Johnson himself offered a specific course for each of these fields, he would have been presiding, mutatis muntandis, over the equivalent of a twentieth-century university."[47]

Johnson also presented a values-focused curriculum, proposing in the Advertisement "in May 1754, to teach student to be “Ornaments to their Country and useful to the public Weal in their Generations” and "to lead them from the study of nature to knowledge of themselves, and of the God of nature and their duty to him, themselves, and one another, and everything that can contribute to their true happiness, both here and hereafter."[48] Once again, the pursuit of happiness was the focus of Johnson's curriculum, his table of philosophy, and his textbook.

In addition to the burden of dealing with the political Presbyterians attacking his college as a devious Anglican plot, and hence leading Presbyterian parents to refuse to send their sons to it, and the usual ramp-up problems of starting a new college, the nine-year-long French and Indian War coincided almost exactly with Johnson's tenure at King's College, drying up funds and draining the pool of potential students while raising fears of invasion. He also had to deal with periodic outbreaks of smallpox, during which he had to leave the college to be run by his tutors for months at a time. Yet he persevered.

In the 22-year period from 1758 to 1776, when the college closed due to the Revolutionary War, 226 men attended, and 113 graduated.[49][50] Among the 83 college students who attended King's College during Johnson's 8+1⁄2-year tenure were some prominent future Loyalists, including Adolph Philipse, Daniel Robart, Abraham De Peyster, and John Vardill. But he taught many more men who became prominent Patriots, including John Jay, Samuel Prevoost, Robert R. Livingston, Richard Harrison, Henry Cruger, Egbert Benson, Edward Antill, Dr. Samuel Bard, John Stevens, Anthony Lispenard, and Henry Rutgers. Among the students taught by his successor Dr. Myles Cooper, were Alexander Hamilton and Gouverneur Morris.

In 1764, he returned to his ministry, replacing as Rector his successor at Christ Church, the Rev. Edward Winslow, who moved to Braintree, Massachusetts. Johnson also began working on another revision of his philosophy. This time Johnson wrote not a textbook but a dialogue titled Raphael, or The Genius of the English America (c. 1764–5), which Johnson called "a Rhapsody". It begins with the arrival of "guardian or genius of New England" of a "beautiful countenance" who tells Arisctocles, named after Aristocles of Messene, and who represents Johnson, to "call me Raphael". His son William Samuel Johnson in 1765 would represent Connecticut at the Stamp Act Congress, and the work hints at the controversies of the period; historian Joseph Ellis suggests that a disillusioned Johnson believed that "the underlying cause of the growing discontent between England and America was the breakdown of a sense of community".[51] Parts of the work praise the British form of Parliamentary government, while others foreshadow the Declaration of Independence, including its core principle that, “The natural obligation to virtue is founded in the necessity that God and nature lays us under to desire and pursue our happiness.”[52] By 1767, Johnson was calling the British ministers in Parliament " a pack of Courtiers, who have no Religion at all.”[53]

In 1767, his son William Samuel Johnson, was appointed Colonial Agent to Great Britain for Connecticut, and left Stratford for London, where he would remain for five years. Johnson was left in Stratford with his daughter-in-law and grandchildren. He continued to minister, teach and write. He also taught prospective Anglican priests in a kind of “little Academy, or resource for young students of Divinity, to prepare them for Holy Orders”.[54] He taught his two grandsons English and Hebrew, as his own grandfather had taught him 70 years before. He wrote for them the first English Grammar (1765) and the first Hebrew grammar (1767) published in America authored by an American. In a 1771 revised edition of Hebrew grammar, he printed his last revision of his table, presenting the sum of all knowledge.

In October 1771, just before he finished his Autobiography, his son William Samuel returned home from London to Johnson's "great and unspeakable comfort and satisfaction".[55] Johnson died a few months later, on January 6, 1772. His protegee and friend President Myles Cooper penned the inscription which adorns his monument in Christ Church, Stratford, where Johnson was minister for most of the 47 years between 1723 and his death, minus the eight and a half years he spent at King's College in New York City.

If decent dignity, and modest mien,

The cheerful heart, and countenance serene;

If pure religion and unsullied truth,

His age's solace, and his search in youth;

In charity, through all the race he ran,

Still wishing well, and doing good to man;

If learning free from pedantry and pride;

If faith and virtue walking side by side;

If well to mark his being's aim and end,

To shine through life the father and the friend;

If these ambition in thy soul can raise,

Excite thy reverence or demand thy praise,

Reader, ere yet thou quit this earthly scene,

Revere his name, and be what he has been.

Personal life

editIn 1725, Johnson married the widow Charity Floyd Nicoll, the mother of three young children, one of whom, William Nicoll, was heir to the vast estate of Islip Grange, in Sayville, New York, then part of a 100 square mile estate on Long Island owned by the Matthias Nicoll family. Johnson acquired close contacts with the leading merchant, legal, and political families of the colonial-era Province of New York, many who sent their sons to board with him in Stratford, to be prepared for college.[56] His first son by Charity, William Samuel Johnson, was born on October 7, 1727; his second son, William "Billy" Johnson, was born on March 9, 1731.

Johnson turned 60 in 1756. That year, he lost his first grandson. The same year, his beloved son William "Billy" died of smallpox on his ordination trip to England. His wife Charity died of smallpox two years later, in 1758. His stepdaughter Anna and his student and wife's nephew Gilbert Floyd died in 1759. His stepson Benjamin Nicoll, his best tutor Daniel Treadwell, and his fellow Great Apostate Rev. Wetmore died in 1760.

On June 18, 1761, Johnson married Sarah Beach, the widow of his old friend William Beach, and his son's mother-in-law, and for a brief time he was "very happy".[57]

In 1762, Johnson and the board of Governors hired the University of Oxford-trained minister Myles Cooper, a young man recommended by the Archbishop of Canterbury, as professor of moral philosophy with the expectation that Cooper would someday succeed him.[58] Johnson quickly bonded with Cooper, who "was with him as a son".[59]

On February 9, 1763, Johnson lost his second wife Sarah to smallpox, and a few weeks after, amidst an unpleasant controversy with the Board of Governors over funding his pension, "he committed the care of his affairs to Mr. Cooper",[60] and returned to Stratford, Connecticut by sleigh during a snowstorm.

Works

editJohnson published his first philosophy work in 1731 as an essay in the English Journal The Republick of Letters; his name also appears as author in 34 books in the English Short Title Catalog printed before 1800.[61] In 1874 Dr. Eben Edwards Beardsley published "portions of diary and of his correspondence with "eminent men in [America], and with Bishops and leading minds in the Church of England" in Life and Correspondence of Samuel Johnson D.D. : missionary of the Church of England in Connecticut, and first president of King's College, New York.[62] In 1929, Herbert and Carol Schneider published a four volume work of Johnson's Career and Writings, reprinting seven of these works. The Schneiders also published for the first time his Autobiography, various letters, a catalog of over 1400 books he read, Synopsis Philosophiae, Encyclopedia of Philosophy, The Revised Encyclopedia, Logic, Miscellaneous Notes, selections from his textbooks on philosophy, Raphael or the Genius of the English America, Reflections on Old Age and Death, twenty-four selected Sermons, various liturgical writings, and various documents relating to the founding of King's College and its early years. Herbert Schneider provides a bibliography of all of Johnson's writings at the end of Volume IV. Many of Johnson's sermons and diaries remain unpublished.

Johnson's major works include:

| 1715 | Encyclopedia of Philosophy in Latin (printed 1929, translation by Herbert Schneider) |

| 1716 | Revised Encyclopedia of Philosophy (1716). (printed 1929 by Herbert Schneider) |

| 1733–37 | Three Letters from a minister of the Church of England to his dissenting parishioners |

| 1743 | An introduction to the study of philosophy exhibiting a general view of all the arts and sciences, for the use of pupils. With a catalogue of some of the most valuable authors necessary to be read in order to instruct them in a thorough knowledge of each of them (a second edition was published in London in 1744) |

| 1745 | A letter from Aristocles to Authades, concerning the sovereignty and the promises of God |

| 1746 | A sermon concerning the obligations we are under to love and delight in the public worship of God |

| 1746 | Ethices elementa. Or The first principles of moral philosophy. And especially that part of it which is called ethics. In a chain of necessary consequences from certain facts (also printed in 1929 in Schneider) |

| 1747 | A letter to Mr. Jonathan Dickinson, in defence of Aristocles to Authades, concerning the sovereignty & promises of God. |

| 1747 | A Sermon Concerning the Intellectual World (published in Schneider, republished in Michael Warner, American Sermons: The Pilgrims to Martin Luther King, Jr., The Library of America, 1999). |

| 1752 | Elementa philosophica: containing chiefly, Noetica, or things relating to the mind or understanding: and Ethica, or things relating to the moral behavior (2 editions, one printed by Benjamin Franklin, one edited by Provost William Smith and printed in London; also printed in 1929 in Schneider) |

| 1753 | A short catechism for young children, proper to be taught them before they learn the Assembly's, or after they have learned the church catechism (2 editions) |

| 1754 | The Elements of Philosophy: containing, I. The most useful parts of logic, including both Metaphysics and Dialectic, or the Art of Reasoning: with a brief Account of the Progress of the Mind towards its highest perfection |

| 1761 | A Sermon on the Beauty of Holiness, in the worship of the Church of England |

| 1764-5 | Raphael, or the Genius of the English America, (printed in 1929 in Schneider) |

| 1767–71 | An English and Hebrew grammar, being the first short rudiments of those two languages, taught together. To which is added, a synopsis of all the parts of learning. (3 editions) |

| 1768 | The Christian Indeed; Explained, in Two Sermons, of Humility and Charity. Preached at NEW-HAVEN, June 28, 1767. |

Reputation

editJohnson has not garnered anywhere near the attention of his student and great rival, the Puritan theologian Johnathan Edwards; he received, for example, only two pages compared to sixteen on Jonathan Edwards in Sydney Ahlstrom's classic work A Religious History of the American People.[63] But he has been admired for his missionary work, his educational ideas, and his philosophy. Johnson has been called "a towering intellect of colonial America, a man of great curiosity and philosophical interests",[64] "the most erudite colonial Anglican theologian of the eighteenth century",[65] "The Founder of American Philosophy",[66] the "first important philosopher in colonial America and author of the first philosophy textbook published there",[67] "the first to give to education that thought and attention which his countrymen have continued to devote to it",[68] the "Father of the Episcopal Church in Connecticut",[69] and "The First Psychological Author in America".[70] His works and his list of books read between 1719 and 1755 have been used to trace the evolution of the American colonial mind by Norman Fiering and Joseph Ellis. He is the subject of two 19th-century biographies, each of which went to two editions; three 21st-century books; a number of book-length dissertations; and is the focus of two 21st-century books.

Influence

editJohnson was among the few colonial Americans whose cultural and intellectual achievements garnered notice in Great Britain. He was a friend of both Bishop George Berkeley and his son, the Rev. George Berkeley, Jr. The author of the English Dictionary, Samuel Johnson of London, was a warm friend of his son William Samuel[71] and "knew of" the other transatlantic Dr. Johnson.[72] The American Dr. Johnson corresponded regularly with English archbishops and bishops, colonial governors, college heads in England and America, and the secretaries of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts.[73]

His influence in the British American colonies was even greater. He was well known at Yale, where he tutored, co-administered the Berkeley scholarship program from its inception in the 1730s, and partnered with President Clap to create an Enlightenment curriculum and reform the college in the 1740s. He created the Anglican church in Connecticut, beginning with parishes founded in 1723 in New Haven, North Haven, and West Haven, and a church he built in 1724 in Stratford. By the time of his death in 1772, there were forty-three churches in the colony.[74] His Anglican disciples had spread out through all thirteen colonies and Canada by 1776. Johnson noted in a 1752 letter to Benjamin Franklin that he had "the great Satisfaction to see some of them in the first pulpits not only in Connecticut but also in Boston and York and others in some of the first places in the Land."[75]

Johnson new-model college reforms spread quickly. Rhode Island College, which is now Brown University, opened in 1764 as a nondenominational college in the "new-model" style not far from where Johnson took philosophical walks with Berkeley.[76]

In 1774, members of the board of trustees of the College of William and Mary, including Benjamin Harrison, Thomas Jefferson, Peyton Randolph, George Wythe, and Thomas Nelson, Jr., who later passed the Lee Resolution and the Declaration of Independence at the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia, proposed to reform the college on the new-model plan of Johnson, Franklin, and Smith, which they accomplished in 1777.[77] During the Revolutionary War, Johnson's protégé, Provost William Smith, would found two more colleges in Maryland: Washington College on the east shore and St. James College on its west shore.

While Johnson's moral philosophy had been taught at Yale since the early 1740s, his most influential textbook on philosophy was his 1752 Elementa Philosophica, a revision and major expansion of his 1731, 1743, and 1746 textbooks on moral philosophy, to include metaphysics and science, made at the request of Benjamin Franklin. In 1752, Franklin printed a fine if expensive first edition in Philadelphia, while a lower-cost second edition printed in London in 1754 appeared with Johnson's corrections and an introduction by Dr. William Smith, provost of the College of Philadelphia. It has been estimated that about half of American college students between 1743 and 1776 were taught Johnson's moral philosophy.[78]

According to Colonial College historian J. David Hoeveler, "In the middle eighteenth century, the collegians who studied" the ideas of the new-model colleges "created new documents of American nationhood."[79] Three members of the Committee of Five who edited the Declaration of Independence were connected to Johnson: his educational partner, promoter, and publisher Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania; his student Robert R. Livingston of New York; and his son's legal and political protégée and Yale treasurer Roger Sherman of Connecticut. Indeed, it has been estimated that fifty-four percent of the contributors to the Declaration of Independence between September 5, 1775, and July 4, 1776, and fifty percent of the men who debated and passed it between June 28 and July 4, 1775, were connected to Johnson or his moral philosophy, making it the dominant morality at the Congress.[80]

Johnson taught many students in his fifty-nine–yearlong career as a teacher in Connecticut and New York. His most important pupil was one of the founders of the American Republic: Johnson was the father of Dr. William Samuel Johnson, a Founding Father of the United States, who attended the Stamp Act Congress, the Continental Congress, the United States Federal Constitutional Convention, and was the first U.S. Senator from Connecticut at the 1st United States Congress, "the only man who attended all four united congresses"[81] that founded America. He followed his father's footsteps, attending Yale and becoming president of Columbia College. A lawyer often called to argue in interstate disputes and a colonial agent to England from 1767 to 1772, he is best known as the chairman of the Committee of Style that wrote the U.S. Constitution: edits to a draft version are in his hand in the Library of Congress.

Legacy

editJohnson's missionary efforts in Connecticut have thrived and expanded. Christ Church, Stratford, remains an active and successful parish. A third church building was built in 1858 in the Carpenter Gothic Style to replace Johnson's 1743 building; but the bell and the golden "brass" rooster weather vane that Johnson donated to the second 1743 church were installed in its steeple, and still call people to worship today. Out of this one church, Johnson founded 26 other churches in Connecticut colony himself, and he lived to see forty-three total founded in the state, with seventeen more founded by his disciples before his death in 1772. Today, there are more than one hundred seventy Episcopalian parishes in the state, serving a membership of nearly sixty thousand people.[82]

Johnson closed his Stratford Common School in 1752, but his name is memorialized in the Stratford Academy's Johnson House, the facility for grades three (3) through six (6). Its motto is Tantum eruditi sunt liberi "Only the educated are free".

The college he founded, King's College, was renamed by the New York Assembly after the Revolutionary War, and is now Columbia University. For over two hundred years, "Columbia has been a leader in higher education in the nation and around the world."[83] In one ranking in 2008, it was tied with two others as the top ranked American university.[84] Nobel Prize winner, Columbia president, and American philosopher Nicholas Murray Butler summed up Johnson's impact as an educator and philosopher: "Suffice it to say here that Samuel Johnson was, with all his obvious limitations, a very remarkable man. No one but a remarkable man could have had his career, have rendered his public service, or have had his vision of what world-wide illumination might follow from the flickering little candle which he lighted in the vestry room of Trinity Church during the summer months of 1754."[85]

In 1999, Johnson's "Sermon Concerning the Intellectual World" was published in Michael Warner's American Sermons: The Pilgrims to Martin Luther King, Jr., an anthology of just fifty-eight American sermons from colonial times to the Civil Rights Movement.[86]

In 2006, the Columbia University Engineering Alumni Association (CEAA) created the Samuel Johnson Medal for Distinguished Achievement Beyond the Realm of Science or Engineering. The medal seeks to commemorate Samuel Johnson's life and emphasis on a well-rounded person applying their training in fields beyond their formal education. The Samuel Johnson Medal honors the highest achievement across the entire arc of human endeavor wherever rigor and methodical thinking and actions are applied beyond the traditional fields of science and engineering. Such fields may include education, law, public affairs, business, social sciences, architecture, and the arts, whether in commerce, public service, or academia.[87][88]

Johnson's moral philosophy did not long outlast the Revolution in college classrooms, as "Scottish realism became the academic prop of American higher education" all the way through "the middle of the eighteenth century".[89] However, Johnson's moral philosophy, defined in his textbook Elementa Philosophica as "the Art of pursuing our highest Happiness by the universal practice of virtue",[90] influenced the core documents of the American Republic, and hence his work is still active in the governing and culture of America as embodied in the phrase, "life, liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness". Dr. Samuel Johnson, along with Dr. Benjamin Franklin and Dr. William Smith, may be considered one of the “Founding Grandfathers” who "first created the idealistic moral philosophy of 'the pursuit of Happiness', and then taught it in American colleges to the generation of men who would become the Founding Fathers."[91] Today, there is once again a great deal of intellectual activity on the philosophy of happiness.[92]

Footnotes

edit- ^ Ellis, Joseph J., The New England Mind in Transition: Samuel Johnson of Connecticut, 1696–1772, Yale University Press, 1973, p. 1.

- ^ Ellis, p. 3.

- ^ Schneider, Herbert and Carol, Samuel Johnson, President of King's College: His Career and Writings, Columbia University Press, 4 vols., 1929, Volume II, pp. 1–22.

- ^ Schneider, Volume II, pp. 56–185.

- ^ Fiering, Norman S., “President Samuel Johnson and the Circle of Knowledge”, The William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, Vol. 28, No. 2 (Apr., 1971), pp. 199–236, p. 201.

- ^ Schneider, Volume I, Autobiography, p.7.

- ^ Schneider, Volume I, Autobiography, p.6.

- ^ Cyclopaedia, or Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences retrieved on September 9, 2013

- ^ Olsen, Neil C., Pursuing Happiness: The Organizational Culture of the Continental Congress, Nonagram Publications, ISBN 978-1480065505 ISBN 1480065501, 2013, p. 147.

- ^ Schneider, Volume I, Autobiography, p. 8

- ^ Dexter, Franklin Bowditch, Documentary history of Yale University: under the original charter of the Collegiate school of Connecticut, 1701–1745,Yale university press, 1916, pp. 158–163.

- ^ Yale, and Johnson, Samuel, Catalogus eorum qui in Collegio Yalensi, quod est Novi-Porti apud Connecticut, ab anno 1702, ad annum 1718 alicujus gradûs laureâdonati sunt, Novi-Londini, Escudebat Timotheus Green, MDCCXVIII (1718).

- ^ Ellis, pp. 44–49

- ^ Ellis, p. 52.

- ^ Ellis, p. 52.

- ^ Schneider, Volume II, pp. 217–244.

- ^ Schneider, Volume I, Autobiography, p.10

- ^ Ahlstrom, Sydney Eckman, and Hall, David D., A Religious History of the American People, Yale University Press, 2004, p. 224.

- ^ Beardsley, Eben Edwards, Life and correspondence of Samuel Johnson D.D.: missionary of the Church of England in Connecticut, and first president of King's College, New York, Hurd & Houghton, 1874, p. 37.

- ^ Olsen, p. 160.

- ^ Olsen, p. 287.

- ^ Seymour, Origen Storrs, The Beginnings of the Episcopal Church in Connecticut, Tercentenary Commission of the State of Connecticut, 1934, p. 5.

- ^ Ellis, p. 127.

- ^ Schneider, Volume I, Autobiography, p. 58.

- ^ Olsen, p. 181.

- ^ Schneider, Volume I, pp. 336–7, 469, II p. 336.

- ^ Schneider, Volume I, Autobiography, p. 28.

- ^ Olsen, p. 158.

- ^ Johnson, Samuel, An Introduction to the Study of Philosophy, New London, 1743, front matter.

- ^ Olsen, p. 160.

- ^ Johnson, Samuel, An Introduction to the Study of Philosophy, p. 1.

- ^ Olsen, p. 159.

- ^ Schneider, Volume III, Sermon IV, pp. 315–326.

- ^ Johnson, Samuel, An Introduction to the Study of Philosophy, p. 1.

- ^ Olsen, p. 158.

- ^ Olsen, p. 160.

- ^ Olsen, p. 160.

- ^ Olsen, p. 160.

- ^ Barnard, Henry, “Samuel Johnson”, The American Journal of Education, Office of American Journal of Education, Volume 7, 1859, Volume 7, p. 446.

- ^ Longaker, Mark Garrett, Rhetoric and the Republic: Politics, Civic Discourse, and Education in Early America, University of Alabama Press, 2007, p. 143.

- ^ Ellis, p. 174.

- ^ Schneider, Volume I, pp. 140–143.

- ^ Ellis, pp. 175–6.

- ^ Olsen, p. 12. See n15, quoting McCaughey, Elizabeth P., From Loyalist to Founding Father:the political odyssey of William Samuel Johnson, Columbia University Press,1980, p. 246.

- ^ Smith, Horace Wemyss, The Life and Correspondence of the Rev. Wm. Smith, D.D., Philadelphia, 1880, Volume 1: pp. 566–567.

- ^ Olsen, p.163.

- ^ Ellis, p. 207, quoting Colonial historian Richard Gummere.

- ^ Schneider, Volume IV, pp. 222–224.

- ^ Schneider, Volume IV, pp. 243–262.

- ^ McCaughey, Robert A., Stand, Columbia : a history of Columbia University in the City of New York, 1754–2004, Columbia University Press, c2003, p.33.

- ^ Ellis, p. 257.

- ^ Schneider, Volume II, p. 536.

- ^ Ellis, pp. 254–255.

- ^ Beardsley, Eben Edwards, The History of the Episcopal Church in Connecticut, Hurd and Stoughton, 1869, Volume 1, p. 268.

- ^ Schneider, Volume I, Autobiography, p. 49.

- ^ Schneider, Volume I, Autobiography, p.58.

- ^ Schneider, Volume I, Autobiography, p. 40.

- ^ Schneider, Volume I, Autobiography, p. 41.

- ^ Schneider, Volume I, Autobiography, p. 41, p. 335.

- ^ Schneider, Volume I, Autobiography, p. 42.

- ^ http://estc.bl.uk/, (W-Names Index= johnson samuel 1696–1772 ADJ). Retrieved on August 24, 2013.

- ^ Beardsley, Eben Edwards, Life and Correspondence of Samuel Johnson, D. D., Hurd & Houghton, 1874

- ^ Ahlstrom, Sidney E., A Religious History of the American People, Yale University Press, 1976, pp. 295–314.

- ^ Hoeveler, J. David, Creating the American Mind:Intellect and Politics in the Colonial Colleges, Rowman & Littlefield, 2007, p. 144.

- ^ Holified, E. Brooks, Theology in America: Christian Thought from the Age of the Puritans to the Civil War, Yale University Press, 2005, p. 87.

- ^ Walsh, James, Education of the Founding Fathers of the Republic: Scholasticism in the Colonial Colleges, Fordham University Press, New York, 1925, p. 185.

- ^ Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Ed. Edward Craig, Taylor & Francis, 1998, p. 124.

- ^ Jones, Adam Leroy, Early American philosophers, Volume 2, Issue 4 of Columbia University contributions to philosophy, psychology and education, The Macmillan Co., 1898, Volume 2, p. 370.

- ^ Seymour, Origen Storrs, The Beginnings of the Episcopal Church in Connecticut, Tercentenary Commission, 1934, p. 5.

- ^ Roback, Abraham Aaron, History of psychology and psychiatry, Philosophical Library, 1961, p. 153.

- ^ Beardsley, Eben Edwards, Life and Times of William Samuel Johnson, LL.D.: First Senator in Congress from Connecticut, and President of Columbia College, New York, Hurd and Houghton, 1876, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Beardsley, Eben Edwards, Life and Times of William Samuel Johnson, LL.D., p. 71.

- ^ Schneider, Letters in Volumes I, II, III, and IV.

- ^ Jarvis, Lucy Cushing (editor), Sketches of Church Life in Colonial Connecticut, Tuttle, Morehouse& Taylor Company, 1902.

- ^ Beardsley, Eben Edwards, Life and correspondence of Samuel Johnson D.D.: missionary of the Church of England in Connecticut, and first president of King's College, New York, Hurd &Houghton, 1874 p. 167.

- ^ Beardsley, Eben Edwards, Life and correspondence of Samuel Johnson D.D.: missionary of the Church of England in Connecticut, and first president of King's College, New York, Hurd &Houghton, 1874 pp. 70-71.

- ^ Olsen, p. 183.

- ^ Olsen, p. 386.

- ^ Hoeveler, J. David, "Creating the American Mind, Rowman & Littlefield, 2007, p. 349.

- ^ Olsen, Appendix I: Morality, pp. 299–300.

- ^ Olsen, p. 287.

- ^ "About the Diocese". Episcopal Diocese of Connecticut. Archived from the original on September 24, 2010. Retrieved June 9, 2023.

- ^ "About Columbia | Columbia University in the City of New York". www.columbia.edu. Retrieved August 24, 2013.

- ^ Toutkoushian, Robert Kevin, and Teichler, Ulrich, University Rankings: Theoretical Basis, Methodology and Impacts on Global Higher Education, Springer, 2011, p. 137.

- ^ Schneider, Volume 1, pp. vi-vii.

- ^ Michael Warner, ed., American Sermons: The Pilgrims to Martin Luther King Jr. (New York: The Library of America, 1999), pp, 365-379.

- ^ "Samuel Johnson Medal". Columbia University Engineering Alumni Association. Archived from the original on September 4, 2012. Retrieved June 9, 2023.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 15, 2016. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Hoeveler, p. 127.

- ^ Schneider, Volume II, p. 372.

- ^ Olsen, p. 13.

- ^ Haybron, Dan, "Happiness", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2011 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2011/entries/happiness/>. Accessed August 26, 2013.

Further reading

edit- Eben Edwards Beardsley, Life and correspondence of Samuel Johnson D.D.: missionary of the Church of England in Connecticut, and first president of King's College, New York, Hurd & Houghton, 1874.

- Peter N. Carroll,The Other Samuel Johnson: A Psychohistory of Early New England, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1978 .

- Thomas Bradbury Chandler, The life of Samuel Johnson, D.D., the first president of King's College, in New York, T. & J. Swords, 1824.

- Joseph J. Ellis, The New England Mind in Transition: Samuel Johnson of Connecticut 1696–1772, Yale University Press, 1973.

- Don R. Gerlach, Samuel Johnson of Stratford in New England, 1696–1772. Athens, GA: Anglican Parishes Association Publications, 2010.

- Elizabeth P. McCaughey, From Loyalist to Founding Father: the political odyssey of William Samuel Johnson, Columbia University Press, 1980.

- Neil C. Olsen, Pursuing Happiness: The Organizational Culture of the Continental Congress, Nonagram Publications, 2009.

- Herbert and Carol Schneider, Samuel Johnson, President of King's College: His Career and Writings, Columbia University Press, 4 vols., 1929.

- Louis Weil, Worship and Sacraments in the Teaching of Samuel Johnson of Connecticut: A Study of the Sources and Development of the High Church Tradition in America, 1722-1789 (doctoral dissertation, 1972)