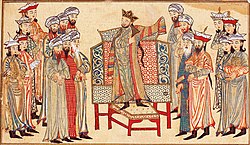

A robe of honour (Arabic: خلعة, romanized: khilʿa, plural khilaʿ, or Arabic: تشريف, romanized: tashrīf, pl. tashārif or tashrīfāt[1]) were rich garments given by medieval and early modern Islamic rulers to subjects as tokens of honour, often as part of a ceremony of appointment to a public post, or as a token of confirmation or acceptance of vassalage of a subordinate ruler. They were usually produced in government factories and decorated with the inscribed bands known as ṭirāz.

History

editThe endowment of garments as a mark of favor is an ancient Middle Eastern tradition, recorded in sources such as the Hebrew Bible and Herodotus.[1]

In the Islamic world, Muhammad himself set a precedent when he removed his cloak (burda) and gave it to Ka'b ibn Zuhayr in recognition of a poem praising him. Indeed, the term khilʿa "denotes the action of removing one's garment in order to give it to someone".[1]

The practice of awarding robes of honour appears in the Abbasid Caliphate, where it became such a regular feature of government that ceremonies of bestowal occurred almost every day, and the members of the caliph's court became known as 'those who wear the khilʿa' (aṣḥāb al-khilʿa).[1] The bestowal of garments became a fixed part of any investment into office, from that of a governor to the heir-apparent to the throne. As important court occasions, these events were often commemorated by poets and recorded by historians.[1]

In Egypt in the Fatimid Caliphate, the practice spread to the wealthy upper middle classes, who began conferring robes of honor on friends and relatives, in emulation of the aristocracy.[1] Later, under the Mamluk Sultanate, the system was standardized into a system of classes reflecting the divisions of Mameluke society, each with its own ranks: the military (arbāb al-suyūf), the civilian bureaucracy (arbāb al-aqlām), and the religious scholars (al-ʿulamāʾ).[1]

The distribution of the robes of honour was the responsibility of the Keeper of the Privy Purse (nāẓir al-khāṣṣ), who supervised the Great Treasury (al-khizāna al-kubra), where the garments were stored.[1] Al-Maqrizi provides a detailed description of the garments worn by the various classes and ranks; in addition, Mamluk practice included the bestowal of arms or even a fully outfitted horse from the Sultan's own stables as a tashrīf.[1] The practice remained very common until the early 20th century; in 19th-century India, the bestowal gift or khillaut (khelat, khilut, or killut) might comprise from five up to 101 articles of clothing.[2]

As the practice spread in the Muslim world, and robes began to be given for every conceivable occasion, they also acquired distinct names. Thus for example the khilaʿ al-wizāra ('robe of the vizierate') would be given on the appointment to the vizierate, while the khilaʿ al-ʿazl ('robe of dismissal') upon an—honourable—dismissal, the khilaʿ al-kudūm might be given to an arriving guest, while the khilaʿ al-safar would to a departing guest, etc.[2]

Sums of money or other valuables were also given as part of the bestowal ceremony, or, in some cases, in lieu of the robe. In the Ottoman Empire, such a sum was known as khilʿet behā ('price of khilʿa'); most commonly this referred to the donativum received by the Janissaries on the accession of a new sultan.[3]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i Stillmann 1986, p. 6.

- ^ a b Stillmann 1986, p. 7.

- ^ Stillmann 1986, pp. 6–7.

Sources

edit- Mayer, Leo Ary (1952). Mamluk Costume: A Survey. A. Kundig.

- Stillmann, N. A. (1986). "K̲h̲ilʿa". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume V: Khe–Mahi. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 6–7. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0507. ISBN 978-90-04-07819-2.

- Stillman, Yedida Kalfon (2003). Norman A. Stillman (ed.). Arab Dress, A Short History: From the Dawn of Islam to Modern Times (Revised Second ed.). Leiden and Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11373-2.