Robert Elliot Pollack (born September 2, 1940) is an American academic, administrator, biologist, and philosopher, who served as a long-time Professor of Biological Sciences at Columbia University.

Robert Pollack | |

|---|---|

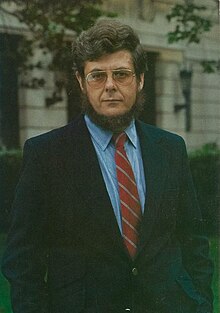

Pollack in 1982 | |

| Born | September 2, 1940 New York City, US |

| Alma mater | Columbia College (BA), Brandeis University (PhD) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Biology |

| Institutions | Stony Brook University, Columbia University |

| Website | https://scienceandsociety.columbia.edu/directory/robert-e-pollack |

Born in Brooklyn, Pollack earned a Bachelor of Arts in physics at Columbia College in 1961. He received a PhD in Biological Sciences from Brandeis University in 1966, and subsequently was a postdoctoral Fellow in Pathology at NYU Langone Health and the Weizmann Institute of Science. He was a senior staff scientist at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory for nearly a decade, before becoming Associate Professor of Microbiology at Stony Brook University in 1975. He returned to Columbia University as a Professor of Biological Sciences in 1978. He served as Dean of Columbia College from 1982 to 1989. He founded the Center for the Study of Science and Religion (CSSR) in 1999, dedicated to exploring the intersection between faith and science. He served as Director of the Columbia University University Seminars from 2011 to 2019. He retired as Director of the CSSR, later renamed to the Research Cluster on Science and Subjectivity, in 2023.

Pollack has been credited as the father of reversion therapy, for his observation that cancer cells infected with different types of viruses could revert to non-oncogenic phenotypes.[1] Subsequently, he published nearly one hundred scientific articles related to reversion. He later became a philosopher, examining his faith with a scientific lens, and, at the same time, reinterpreting science through faith. Pollack has authored over 200 scientific articles, seven books, and dozens of speeches, mostly delivered at Columbia University.

As the first Jewish Dean of an Ivy League institution, Pollack faced significant fundraising challenges, the AIDS epidemic, and conflict surrounding the issue of South African divestment. Being a scientific activist, he was the first to raise concerns about recombinant DNA technology, which eventually led to the Asilomar Conference. He also decried the corrupting relationship between scientific academia and industry and promoted scientific literacy among the general public. He set the stage for the inclusion of science in the Columbia College Core Curriculum. He ultimately converted the Research Cluster on Science and Subjectivity to an institution promoting undergraduates, encouraging a legacy of student-centered innovation. He has collaborated with and mentored many prominent scientists, including Nancy Hopkins and Bettie Steinberg.

Education and early life

editRobert Elliot Pollack was born on September 2, 1940, in Brooklyn, NY, growing up in the neighborhood of Seagate.[2] His parents did not finish high school;[3] his father ran a factory, manufacturing cardboard boxes.[2] He attended Abraham Lincoln High School and studied at Columbia College, graduating in 1961 with a physics major.[4] While at Columbia, he was a member of Jester Magazine[5] and Columbia Daily Spectator.[6][7][8][9] He took a freshman Core Course with Robert Belknap,[10] whom he later succeeded as the Director of University Seminars at Columbia University.[11] His favorite professors were Sidney Morgenbesser and Richard Neustadt, who taught philosophy and government, respectively.[2] He worked as a laboratory assistant under the direction of Arno Penzias, then a graduate student in the lab of Charles H. Townes.[12] Upon graduation, Pollack received a New York State Regents Teaching Fellowship to pursue graduate work at Brandeis University,[13] examining differential expression of leucine transfer RNA in different strains of Escherichia coli following T2 or T4 virus infection.[14]

Research

editIn 1968, while working for Howard Green, Pollack published the first demonstration of reversion, a phenomenon whereby certain cancer cells demonstrated decreased growth and increased contact inhibition, thereafter being considered as reverted to a more normal non-oncogenic phenotype.[15] Reversion was later suggested as a potential treatment for cancer.[16] Pollack's work sparked a novel subfield of oncogenic research, elucidating the distinct mechanisms directing cell reversion.[17]

Academic career

editMicrobiologist

editGraduating with a PhD in Biology from Brandeis University in 1966, he spent sixteen years as a research scientist, completing postdoctoral work at both N.Y.U. Medical Center and the Weizmann Institute in Israel. He thereafter served as a senior scientist at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory from 1971 to 1975, became an Associate Professor of Biology at Stonybrook University from 1975 to 1978, and finally headed his own laboratory as a full Professor of Biology at Columbia University from 1978 to 1994.[2]

Dean of Columbia College

editPollack served as Dean of Columbia College from 1982 to 1989.[18][19] At the time of his appointment, the College was firmly in the Sovern era, facing a severe financial crisis, student protests related to South African divestment and concerns regarding the quality of student life, following the institution of co-education and subsequently declining admissions rates.[20][21][22][23] During his tenure, he joined with the Columbia College faculty to oppose a merger with the faculties of other schools at Columbia University.[24] Upon his resignation, he was praised for his honesty, independence, and involvement in student affairs.[25][26][27][28][29][30][31]

Academic Initiatives

editPollack took a variety of academic stances during his tenure. At his encouragement, the faculty of the College voted to move up the pass-fail course registration deadline by one month.[32] Pollack opposed the inclusion of computer science in the Core Curriculum.[33] Pollack organized faculty committees to examine the development of additional majors in both African-American studies and gender studies.[34][35] In 1983, Pollack awarded an honorary degree to Isaac Asimov, who had been forced due to racial quotas to attend Seth Low Junior College, later folded into the Columbia University School of General Studies.[36][37][38]

Pollack supported the founding of the Rabi Scholar's cohort, named after Nobel Laureate Isidor Isaac Rabi.[39] The program is designed to encourage talented students in the sciences to attend Columbia College.[40] In 1989, Pollack applied for and received a one million dollar grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, aimed at enhancing undergraduate science education and community outreach, which ensured long-term financial support for the Rabi Scholars program.[41] Additionally, he founded the Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship program in the Department of Biology, funding students pursuing on-campus summer research internships.[42] He encouraged these students to consider careers in academic post-graduation.[43]

Student Life

editNotably, Pollack oversaw the admission of the first female-inclusive class in 1983,[44][45] appointing a co-education coordinator to facilitate the transition.[46][47][48] At the same time, he engineered a merger between the athletics programs of Barnard College and Columbia College.[49] He pushed for renovations to the main student life center, later rebuilt as Alfred Lerner Hall.[50]

Pollack forwarded initiatives to ensure guaranteed housing for all students.[51][52] A contemporary editorial by the Managing Board of the Columbia Daily Spectator noted that: "College Dean Robert Pollack is clinging to his guarantee of housing for all freshmen like a mother bear to its threatened cub."[53] In addition to the acquisition of the Carlton Arms dormitory, he pushed for the construction of a new dorm on 115th street,[54] which eventually became Schapiro Hall.[55] He successfully convinced Morris Schapiro to donate an addition two million dollars to fund a student center for the arts in the basement of this dorm.[56] Additionally, the college negotiated directly with manufacturers to install computer labs in residence.[57]

In the face of significant financial constraints,[58][59][60] Pollack vigorously and successfully defended Columbia College's need-blind admissions policy with alumni donations.[61][62][63] A focus within his tenure was to support a more racially and ethnically diverse student body.[64][65][66] To this end, he supported the development of an intercultural resource center, bolstering undergraduate student life.[67][68][69]

AIDS Epidemic

editPollack was one of the first university administers to meet with LGBTQ groups during the AIDS epidemic.[70] He later led an initiative to formulate an AIDS-related policy for Columbia's campus.[71][72][73] Additionally, Pollack called for the development of an AIDS vaccine.[74]

South African Divestment

editIn response to increasing student activism related to divestment from South Africa, the Columbia University Senate voted on March 25, 1983, to recommend total divestment, which was in turn rejected by the Trustees of the University.[75] In response, the University Senate appointed Pollack, alongside Louis Henkin and then-student Barbara Ransby, to a seven-member committee, charged with researching university divestment and reporting their results to the trustees.[76] Pollack was selected to chair the committee.[77] Due to opposition from Ransby, the report could not be presented to the University Senate by the end of the 1984 academic year.[78][79] In response, Pollack directly requested that Columbia University President Michael Sovern recommend that the trustees freeze investments in South Africa,[80] a principal recommendation of the report, which thereafter became known as the Pollack Report.[81][82][83] The trustees responded favorably to Pollack's request, instituting a freeze on new investments in June, 1984.[84] The committee, containing a new student representative,[85] approved the report on November 15, 1984,[86] followed by ratification in December, 1984 by the University Senate.[87] In addition to a freeze on investments, the report recommended the formation of a consortium of universities to organize against apartheid, the continuous monitoring of current South African investments by a standing committee, and the funding of educational programs to study social politics in South Africa.[88] Although Pollack strongly defended the committee's work,[89] student activists continued to push for total divestment, organizing a fast[90] and protest simultaneously,[91] blockading the entrance to Hamilton Hall for three weeks.[92][93][94] While the trustees accepted only three proposals from the Pollack Report, choosing to maintain the temporary investment freeze agreed to with Pollack in 1984,[95] a worsening human rights situation in South Africa led Pollack and other university administrators to also push for total divestment.[96] The trustees thereafter accepted a two-year divestment plan in October, 1985, making Columbia University the first private institution to move toward total divestment.[97][98][99] In order to fund the educational programs recommended by the Pollack Report, the University received a one million dollar grant in 1986 from the Ford Foundation to support interdisciplinary courses in human rights.[100]

Columbia College Bicentennial

editIn 1987, Columbia College celebrated its bicentennial, commemorating the signing of the College charter, in 1987.[101][102] Pollack led a series of reflection sessions in advance of the event, championing recent advances in African American and Women's studies.[103][104][105][106] He later gave speeches at major gatherings and parades, celebrating the close ties between Columbia College and New York City.[107][108][109]

Racial Tensions at Columbia

editProtests by hundreds of students erupted following a racially motivated fight between students in the College in March, 1987.[110][111] In response, Pollack organized a meeting between black student leaders and Columbia University President Michael Sovern.[112][113][114] Sovern next met with the Columbia College student council, yielding limited results.[115] As a result, approximately one month later, student leaders organized a protest blockading Hamilton Hall, reminiscent of the protests during South African Divestment.[116] 50 students were arrested, sparking a nearly one thousand person strong protest.[117][118] In response, Pollack released a report regarding the March 22nd fight, charging junior Drew Krause with racial harassment and suspending him for one semester.[119][120][121][122] In response, Krause sued Columbia University for discrimination, winning in federal court and overturning his suspension.[123][124] When the University appealed this ruling, the two parties entered arbitration, settling outside of court.[125][126]

In 1984, Pollack came out against an African-American studies major, favoring a more broadly encompassing minority studies major.[127] Therefore, in 1986, minority studies became an approved major, while proposals for African-American studies languished.[128][129] Four days after the March 22nd fight, the African-American studies proposal was brought before the committee on instruction with Pollack's approval, and ratified by the faculty nearly a month afterwards.[130][131][132] Therefore, the 1987-1988 academic year therefore became the first where African-American studies was an offered major.[133]

Over the course of the Fall, 1987 semester, Pollack developed a plan to use a 25 million dollar donation from John Kluge to encourage graduate studies for underrepresented groups.[134][135] He additionally appointed a race relations committee, headed by Professor Charles Hamilton.[136] The committee provided fourteen recommendations, accepted by Pollack, including an investment in the Columbia University Double Discovery Center along with increased hiring of minority faculty.[137][138][139]

Research Contributions During Deanship

editAlongside his administrative responsibilities, Pollack maintained an active role in scientific research.[140][141] His work focused on understanding the molecular mechanisms of cellular differentiation and cancer cell transformation, specifically investigating the role of viral proteins and the cellular cytoskeleton in oncogenesis. Notable publications include studies on insulin binding by 3T3 cells,[142] the role of the cytoskeleton in colonic epithelial cells,[143] and adipocyte differentiation by DNA transfection.[144] Additionally, he spoke out regarding the relationship between academia and industry science.[145][146]

Co-Chair of the Jewish Campus Life Fund

editNear the end of his term as Dean and afterwards, Pollack was considered for a wide variety of academic positions at other universities, including as provost at University of Pennsylvania,[147][148] as president of University of Vermont,[149][150] as president of Bowdoin College,[151] and as president of Brandeis University.[152] He ultimately continued as Professor of Biological Sciences at Columbia University, becoming the Co-Chair of the Jewish Campus Life Fund.[153][12] In this role, he convinced Robert Kraft to donate the necessary funds to establish the Robert K. Kraft Family Center for Jewish Student Life at Columbia, which opened in 2000.[154][155][156][157][158] He continued to comment on current issues, defending David Baltimore during the Imanishi-Kari case[159] and advocating for need-blind admissions policies.[160]

He was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1993 to write a book on the definition of disease.[161][162] From these efforts arose Pollack's first book geared for the general public, entitled Signs of Life: the Language and Meanings of DNA (1994).[163][164] In 1999, Pollack published his second book, The Missing Moment: How the Unconscious Shapes Modern Science (Houghton Mifflin), which offers reflection on mortality, morality, and the role of science in society.[165] The Missing Moment ultimately critiques the biomedical field's tendency to overlook human needs by operating within a paradigm that denies personal mortality.[166]

Director of the Center for the Study of Science and Religion

editPollack founded the Center for the Study of Science and Religion, later renamed the Research Cluster for Science and Subjectivity, in 1999, receiving a number of notable grants to power its operations, spanning diverse colloquial efforts, undergraduate course support, and a medical writer-in-residence program.[167] In 2000, he published The Faith of Biology and the Biology of Faith: Order, meaning and free will in modern science, examining the relationship between religious belief and scientific practice.[168] Originally presented at the Columbia University Seminar 1999 Leonard Hastings Schoff Memorial Lecture,[169] the text was republished in 2013, with a new preface emphasizing individual responsibility over scientific institutions, in discussing the role of free will in scientific practice.[170] He participated in a 2003 interview with Robert Wright, underscoring Pollack's approach to finding balance and meaning at the intersection between scientific inquiry and spiritual belief.[171] He partnered with Jeffrey Sachs, moving the CSSR to the Earth Institute, turning his attention to the study of climate change during the later 2000s.[172]

From 2011 to 2019, Pollack concurrently served as the Director of the Columbia University seminars, a movement fostering interdisciplinary conversations between academics, founded by Frank Tannenbaum.[173][174][175][176] In his role as Director, he played an important role in the creation of the University Seminar Archive.[177]

Starting in 2014, Pollack changed the mission of the RCSS to focus on empowering undergraduate projects.[178] He received an endowment from College alumnus Harvey Krueger ’51 to perpetually fund these undergraduate efforts.[179] An exemplar of this vision is the fully-funded Black Undergraduate Mentorship Program in Biology at Columbia, providing summer research housing stipends and significant individualized mentorship, with support from both Harmen Bussemaker and Nobel Laureate Martin Chalfie.[180] Pollack retired as director in 2023.[181] He continues to serve on the advisory board of the RCSS and as an executive committee member for the Columbia University Center for Science and Society.[182][183]

Teaching

editCold Spring Harbor Laboratory

editAs a research scientist in Nobel Laureate James Watson's laboratory,[184] Pollack taught a yearly summer course on animal cells and viruses.[185] In 1971, his class heard a presentation from Janet Mertz, then a graduate student in the laboratory of Paul Berg, who proposed an experiment cloning SV40 genes from monkeys into bacteria.[186] Pollack reacted to this presentation by directly calling Berg to relay his concerns and drafting an unsent letter calling for a moratorium on this kind of cloning.[187][188] His concerns centered on the potential for these bacteria to be capable of inducing cancer, which could possibly spread rapidly through the human population.[189] Berg accepted these concerns, starting a voluntary moratorium.[190] In 1973, a conference was held at Asilomar, with Pollack editing the proceedings into a book entitled Biohazards in biological research, specifically identifying the necessary experiments to deem recombinant DNA technologies safe.[191] In 1974, this expanded into the first national moratorium on a specific subset of scientific research, followed by the more-famous Asilomar Conference in 1975, which answered many of the safety concerns recombinant DNA technologies raised at the 1973 conference, thereby paving the way to lift the national moratorium.[192] The response of the scientific community to recombinant DNA technologies has been scrutinized in debates regarding CRISPR-based genome modification technologies.[193]

Columbia University

editPollack has taught a variety of lecture and seminar style courses at Columbia University, including, [BIOL W2001] Environmental Biology, [BIOL W3500] Independent research, [BIOL G4065] Molecular Biology of Disease, [RELI V2660] Science & Religion East & West, and [EEEBGU4321] Human Nature: DNA, Race & Identity: Our Bodies, Our Selves.[194][195] Arriving at Columbia in 1978,[196] he soon joined the Columbia College Committee on Instruction,[197] responsible for approving academic policy changes, new courses, and new major proposals.[198] Pollack has been a consistent supporter of the Core Curriculum as a mandatory component of undergraduate education.[199][200]

Pollack was an early advocate for the inclusion of science curriculum within Columbia's Core Curriculum.[201][202][203] To accomplish this goal, Pollack, alongside Herbert Goldstein and Jonathon Gross, developed a course entitled the Theory and Practice of Science, aimed at providing scientific literacy to the general student population, funded by a $30,000 grant from the Exxon Mobil Foundation along with an anonymous $30,000 donation, later revealed to be a personal donation from Columbia University President Michael Sovern.[204][205][206] Based on a belief that fundamental scientific papers double as literary masterpieces,[207] Pollack's portion of the course was organized around key publications in biochemistry, evolution, and genetics.[208][209] In 1983, the course received an additional $240,000 in support from the Mellon Foundation.[210] Although the course was taught for at least fourteen years,[211] it failed enter the core curriculum, due to concerns regarding the breadth of technical concepts within the discussed works.[212] Pollack later contributed[213] to and taught[214] in Frontiers of Science,[215] a general science curriculum developed by David Helfand[216] and Darcy Kelley, former instructors for The Theory and Practice of Science,[217] which was added to the Core Curriculum in 2005.[218][219][220]

Awards and honors

editPollack has received the Alexander Hamilton Medal from Columbia University, Columbia College's most distinguished award for alumni.[221] He has additionally received the Gershom Mendes Seixas Award from the Columbia/Barnard Hillel organization.[222] His book Signs of Life: the Language and Meanings of DNA (1994)[223] received the Lionel Trilling Award.[224] In 1986, he was appointed by NYC mayor Ed Koch to an advisory committee on science and technology.[225]

Personal life

editPollack is married to Amy Steinberg, an artist.[226][227][228] They co-authored The Course of Nature: A Book of Drawings on Natural Selection and Its Consequences (2014), consisting of Steinberg's drawings and Pollack's commentary.[229] Their daughter Marya Pollack, who graduated as a member of the first coeducational class of students from Columbia College in 1987,[227] is an attending physician at New York Presbyterian Hospital and Assistant Clinical Professor in Psychiatry at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons.[230]

Books

editIn addition to his academic and administrative positions, Pollack has written many articles and books on diverse subjects, ranging from laboratory science to religious ethics.

- Readings in mammalian cell culture, first edition (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 1975) ISBN 0879691166

- Readings in mammalian cell culture, second edition (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 1982) ISBN 9780879691370

- Signs of Life: The Language and Meanings of DNA (Houghton Mifflin, 1994) ISBN 0395735300

- The Missing Moment: How the Unconscious shapes Modern Science (Houghton Mifflin, 1999) ISBN 0395709857

- The Faith of Biology and the Biology of Faith (Columbia University Press, 2000) ISBN 9780231529051

- The Faith of Biology and the Biology of Faith, With a New Preface by the Author (Columbia University Press, 2013) ISBN 9780231115070

- The Course of Nature: A Book of Drawings on Natural Selection and Its Consequences (Stony Creek Press, 2014) ISBN 1499122241

References

edit- ^ Telerman, A; Amson, R; Hendrix, MJ (August 2010). "Tumor reversion holds promise". Oncotarget. 1 (4): 233–4. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.131. PMC 3248106. PMID 21304173.

- ^ a b c d Katz, James C. (September 1, 1982). "Around the Quads: A life spent asking questions". Columbia College Today.

- ^ Pollack, Robert. "Commemoration of Robert Belknap" (PDF). Columbia University - Department of Biological Sciences.

- ^ Gelder, Lawrence Van (October 2, 1983). "STUDY OF LIFE LEADS TO LIFE AS DEAN". New York Times. ProQuest 424798602.

- ^ "Elect Paul Nagano New Jester Head". Columbia Spectator. April 13, 1959.

- ^ "The Supplement". Columbia Spectator. November 18, 1960.

- ^ "The Supplement". Columbia Spectator. December 13, 1960.

- ^ "The Supplement". Columbia Spectator. February 17, 1961.

- ^ "The Supplement". Columbia Spectator. March 16, 1961.

- ^ Pollack, Robert. "Commemoration of Robert Belknap" (PDF). Columbia University - Department of Biological Sciences.

- ^ "About Bob Pollack". WordPress. 18 October 2013.

- ^ a b Pollack, Robert. "Seeing and Knowing". Columbia Current.

- ^ "71 Fellowships Won by Seniors". Columbia Spectator. June 5, 1961.

- ^ Pollack, Robert E. (1 July 1966). "Changes in Leucine-Specific sRNA after Infection of E. coli by Phages T2 and T4". Journal of General Physiology. 49 (6): 1139–1145. doi:10.1085/jgp.0491139. PMC 3328318. PMID 5332365.

- ^ Pollack, R E; Green, H; Todaro, G J (May 1968). "Growth control in cultured cells: selection of sublines with increased sensitivity to contact inhibition and decreased tumor-producing ability". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 60 (1): 126–133. Bibcode:1968PNAS...60..126P. doi:10.1073/pnas.60.1.126. PMC 539091. PMID 4297915.

- ^ Powers, Scott; Pollack, Robert E. (April 2016). "Inducing stable reversion to achieve cancer control". Nature Reviews Cancer. 16 (4): 266–270. doi:10.1038/nrc.2016.12. PMID 27458638. S2CID 25582297.

- ^ Cho, Kwang-Hyun; Lee, Soobeom; Kim, Dongsan; Shin, Dongkwan; Joo, Jae Il; Park, Sang-Min (April 2017). "Cancer reversion, a renewed challenge in systems biology". Current Opinion in Systems Biology. 2: 49–58. doi:10.1016/j.coisb.2017.01.005.

- ^ "Deans of the College". Columbia College.

- ^ "METRO DATELINE; Dean of Columbia Plans To Step Down". New York Times. April 15, 1989.

- ^ Sandomir, Richard (22 January 2020). "Michael I. Sovern, Who Led Columbia in Eventful Era, Dies at 88". The New York Times.

- ^ Pomper, Miles (April 16, 1987). "CC admissions increase more than any other Ivy". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ WIMPHEIMER, AHUVA (April 28, 1997). "Columbia examines consequences of co-education". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ RUGGIERO-CORLISS, ANGELA (April 1, 2009). "Reception honors anniversary of CC coeducation". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Connor, Tracy (October 20, 1987). "CC profs resolve to oppose faculty merger at meeting". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Hardt, Robert J.; Botkin, Joshua (April 13, 1989). "Columbia College Dean Robert Pollack resigns". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Hall, Rachel; Schultz, Evan P. (April 13, 1989). "Faculty members speculate reasons dean is resigning". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Kaufman, David; Sehgal, A. Cassidy (April 13, 1989). "Student leaders criticize Pollack's record". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Landau, Lisa; Pustilnik, Alix (May 17, 1989). "Pollack's progress". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Schultz, Evan P. (May 24, 1989). "Wouk reminisces CC experience". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Schultz, Evan P. (May 31, 1989). "Search committee for CC Dean begins nominations". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Markowitz, Murray (February 22, 1991). "Remembering the way things were". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Schultz, Evan P. (February 27, 1989). "CC faculty votes to move pass-fail date up a month". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ LoPRESTI, MARY ANN (March 20, 1985). "Comp sci requirement debated". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ BENDAVID, NAFTALI (November 21, 1983). "Panel weighs gender studies". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Tucker, Irene (November 12, 1985). "Group meets on black studies". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Oppenheimer, Mark. "Ep. 1: Columbia and Its Forgotten Jewish Campus". Gatecrashers. Tablet Magazine.

- ^ Gohn, Claudia (April 15, 2019). "Nearly a Century Ago, Columbia's Jewish Applicants Were Sent to Brooklyn". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Craig, Jeffrey (May 17, 1983). "Last all-male College class to graduate today". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ "College Briefs". Columbia Spectator. 4 April 1989. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ "Rabi Scholars Program fosters community among science students". Columbia Spectator. 2 March 2005. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ Evan Ambinder (31 May 1989). "CU receives million dollar science grant". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Vadino, Diane (October 31, 1994). "Undergraduate researchers present findings". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Gat, Michael (November 30, 1983). "There is life after CC: Pollack". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Froehlich, Richard (April 6, 1982). "CC biology prof picked to be new College dean". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Staff, Spectator (August 29, 1983). "At Last 229-year tradition ends as College women arrive". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Froehlich, Richard (November 19, 1982). "CC looks for coordinator to ease coed transition". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Froehlich, Richard (December 6, 1982). "College still has to pick coordinator for coeducation". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Bashman, Howard (February 22, 1983). "CC picks coed coordinator". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Greene, Liz; Butler, Charles (March 3, 1983). "Bears turn into Lions: consortium is okayed Athletes, coaches pleased with deal". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Oswald, John (November 5, 1986). "FBH fix-up stalls over budgeting". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Adler, Philippe (August 29, 1984). "College looks to future with high hopes". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ "Housing Guaranteed to All Undergraduates". Columbia Spectator. December 13, 1999.

- ^ "Remember The Carlton?". Columbia Spectator. September 6, 1983.

- ^ Froehlich, Richard (August 11, 1982). "Columbia contemplating increase in class size, dorm to go on 115th". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Berger, Joseph (1988-08-26). "New Dorm at Columbia Means Diversity". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-11-14.

- ^ Phillip, Francis. "Schapiro Hall to have first CU arts center". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Bashman, Howard J. (January 24, 1984). "CC diversifies in computer uses". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Bashman, Howard (January 25, 1983). "CU puts aid limit on College, SEAS May end need-blind admissions". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ "MISSING PIECES: SEAS may deny aid". Columbia Spectator. February 3, 1983.

- ^ Genachowski, Julius (February 11, 1983). "Low Library aid policy jeopardizes need-blind CC, SEAS scramble for aid funds". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Lewis, Mark (March 7, 1983). "CC, SEAS using new tactics to get gifts". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Kornhauser, Anne (April 11, 1983). "CC gets $1 million for financial aid from Beller family". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ "Editorials: Need-blind must stay top priority". Columbia Spectator. February 20, 1984.

- ^ Lynch, Hollis R. (February 22, 1983). "After bad start, CU must be more representative". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Cameron, Roger (February 28, 1983). "Prospective minority students lured in weekend". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ MIRANDA, MOLLY (February 25, 1998). "1983-1998: 15 years of change for Columbia Diverse and co-ed: The changing student body". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ BENDAVID, NAFTALI (September 19, 1984). "Student groups seek center for minorities". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ TUCKER, IRENE (November 15, 1985). "Intercultural center seeks outside funds". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ BAYER, AMY (October 29, 1986). "UMB leaders angered by FBH space allotted". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Gat, Michael (October 27, 1983). "Pollack, gay students discuss AIDS, harassment at forum". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Editorial Board (September 10, 1985). "AIDS and Columbia". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ FREEDMAN, ALLAN (September 10, 1985). "CU officials to start discussions on AIDS". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ FREEDMAN, ALLAN (September 18, 1985). "Group will define AIDS policy". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Pollack, Robert E. (November 27, 1985). "For a National Effort to Develop A Vaccine to Counteract AIDS: It is feasible and overdue". New York Times.

- ^ Froehlich, Richard (September 26, 1983). "Senate rethinks pro-divest stance". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Froehlich, Richard (October 17, 1983). "Senate forms new panel on S. Africa". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Schimek, Paul (October 17, 1983). "University can set precedent on divestment issue: Pollack". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Bashman, Howard J. (April 19, 1984). "One holds out on investment report". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Bashman, Howard J. (April 26, 1984). "Ransby opposes plan to freeze investment". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Bashman, Howard J. (May 16, 1984). "Trustees to consider freeze option on S.A." Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Feldman, Jeremy J. (June 13, 1984). "Pollack and Sovern become focus of divestment debate". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ "Editorial: What happened to divestment?". Columbia Spectator. November 26, 1984.

- ^ "The Pollack Committee Report". Columbia College Today. June 1, 1985.

- ^ Feldman, Jeremy J. (June 6, 1984). "Trustees freeze investments". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Kornhauser, Anne (October 5, 1984). "Students critical of divest panel appointment". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Kornhauser, Anne (November 16, 1984). "Pollack group finally okays report". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Kornhauser, Anne (December 3, 1984). "Senate passes S. Africa freeze resolution". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ "Spectrum S. Africa: Freeze or thaw? The four point plan". Columbia Spectator. November 29, 1984.

- ^ Pollack, Robert (November 29, 1984). "From the Committee: Freeze is not a 'compromise'". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Murphy, Jacqueline Shea (March 25, 1985). "Coalition begins protest fast today". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Schwartz, Elizabeth; Kornhauser, Anne (April 7, 1985). "Hamilton blockade In 4th day; 8 students warned; fast still on". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ "Protestors blockade Hamilton". Columbia Spectator. April 5, 1985.

- ^ Kornhauser, Anne (April 12, 1985). "Talks end between blockaders and CU: No agreement on amnesty issue". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Rohter, Larry (April 5, 1985). "COLUMBIA STUDENTS TO END ANTI-APARTHEID PROTEST". New York Times.

- ^ Murphy, Jacqueline Shea (July 24, 1985). "Trustees delaying freeze decision". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ West, Steve (August 28, 1985). "S. Af. freeze decision is postponed". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Kornhauser, Anne (August 29, 1985). "CU plans full divestment". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Schoolmeester, Kelly (July 2, 2010). "Columbia University students win divestment from apartheid South Africa, United States, 1985". Swarthmore College.

- ^ West, Steve; Lynch, Jennifer (October 8, 1985). "Trustees vote for divestment". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Chipman, Andrea (February 19, 1986). "Ford grant to expand human rights center". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Winship, Frederick M. (April 13, 1987). "Columbia College, the nation's oldest state-chartered college, celebrated its". United Press International, Inc.

- ^ Carmody, Deirdre (April 5, 1987). "Columbia Celebrates Its Bicentennial (Again)". New York Times.

- ^ "Reflections on the College". Columbia Spectator. February 18, 1987.

- ^ Michelson, Melissa (February 23, 1987). "Bicentennial celebration to start with reflections". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ "Reflections on the College". Columbia Spectator. February 25, 1987.

- ^ Michelson, Melissa (February 26, 1987). "From Pollack to Navab: CC remembers 200 years". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Michelson, Melissa (April 8, 1987). "Students apathetic about bicentennial". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Michelson, Melissa (April 13, 1987). "Koch joins speakers in praise of Columbia and its charter". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Michelson, Melissa (April 14, 1987). "150 gather in St. Paul's to celebrate charter day". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Drew, Duchesne Paul (March 23, 1987). "Racial tensions explode following weekend brawl". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Justice, Jade; Cheng, Annie (March 17, 2021). "The Fight, The Movement, and The Backlash: Columbia's Reckoning with Racism in 1987". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Drew, Duchesne Paul (March 25, 1987). "Sovern to meet with black leaders". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Drew, Duchesne Paul (March 27, 1987). "Black student group meets with CU president today". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Oswald, John A.; Drew, Duchesne Paul (March 30, 1987). "Black students disappointed with first Sovern meeting CBSC may join CC discipline procedure". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Pomper, Miles (March 31, 1987). "Council calls Sovern meet about CU racism fruitless". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Drew, Duchesne Paul (May 13, 1987). "A spring of dissent: Columbia faces racism Fight leads to protests, blockade, and police arrests". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Staff, Spectator (April 22, 1987). "Sovern calls in police to end blockade". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Earle, Jonathan; Gillette, Josh (April 23, 1987). "1,000 attend Low Library protest yesterday". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Oswald, John A. (March 26, 1987). "CC disciplinary hearings proceed without key input". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Drew, Duchesne Paul; Pomper, Miles (April 23, 1987). "CC report disciplines one Deans say race harassment occurred". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ "Deans release Columbia College report about race incident". Columbia Spectator. April 23, 1987.

- ^ "Blockade aftermath". Columbia Spectator. April 23, 1987.

- ^ "White Columbia Student Ia Ruled Bias Victim". New York Times. January 13, 1988.

- ^ Oswald, John A. (January 25, 1988). "Jury rules for Krause, says deans discriminated". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Hardt, Jr., Robert (February 4, 1988). "Columbia to appeal discrimination case". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Hardt, Jr., Robert (February 24, 1988). "University and Krause settle out of court". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Chung, Alton (December 3, 1984). "University sees need for minority courses". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Bayer, Amy (May 14, 1986). "Minority studies major approved". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Gilette, Josh (September 23, 1986). "Afro-American proposal readied for end of year". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Michelson, Melissa (March 26, 1987). "COI to consider black studies major". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Michelson, Melissa (April 9, 1987). "Afro-American major receives COI go-ahead". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Michelson, Melissa (April 23, 1987). "Faculty approve African studies major". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Pollack, Robert (March 25, 1988). "Staying serious on African-American studies". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ WongSam, Annie-Marie (September 10, 1987). "Kluge gift to aid minority Ph.D. students". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Kanthak, Kris (December 5, 1989). "Minorities struggle for strong presence at Columbia Divestment battle, racial brawl mar CU's affirmative action efforts". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Hardt, Jr., Robert (May 18, 1988). "Race relations comm report released tues". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Gillette, Joshua C. (September 20, 1988). "Hamilton report suggests means to improve race relations on campus". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Gillette, Joshua C. (September 21, 1988). "Hamilton report: admins must back minority hiring". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Moffitt-Hawasly, Kelly (August 16, 2023). "Community Leaders Visit Columbia's Flourishing Double Discovery Center College Prep Program for Local Students". Columbia Neighbors.

- ^ Stiefel, Larry (April 6, 1984). "Pollack still loves life in the laboratory". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ "Columbia Dean Finds Time for Cancer Research". New York Times. December 9, 1984.

- ^ Murphy, R.; Powers, S.; Cantor, C.; Pollack, R. (1982). "Insulin binding by 3T3 cells". Cytometry. 2 (6): 402–406. doi:10.1002/cyto.990020608. PMID 6804197.

- ^ Friedman, E.; Verderame, M.; Winawer, S.; Pollack, R. (1984). "Cytoskeleton in colonic epithelial cells". Cancer Research.

- ^ Chen, S.; Kazim, N.; Kravecka, J.; Pollack, R. (1989). "Adipocyte differentiation by DNA transfection". Science. 244 (4904): 582–585. doi:10.1126/science.2470149. PMID 2470149.

- ^ Pollack, Robert (October 1982). "Biologists in Pinstripes". The Sciences. 22 (7): 35–37. doi:10.1002/j.2326-1951.1982.tb02104.x. PMID 11650586.

- ^ Pollack, Robert (April 5, 1983). "Biologists in Pinstripes". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Connor, Tracy; Luhby, Tami (July 15, 1987). "Pollack considered for Penn Provost spot". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Connor, Tracy (July 29, 1987). "CC Dean Pollack not chosen for Penn provost spot". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Danis, Kirsten (April 19, 1990). "Pollack: Next UVM prez?". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Reza, Elizabeth (July 18, 1990). "Pollack nixed for UVM spot". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Pollack, Robert (November 11, 1989). "Handwritten letter from Robert Pollack to James D. Watson". CSHL Archives Repository.

- ^ Roston, Eric (February 22, 1991). "Former CC dean up for Brandeis job". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ TELLER, DAVID (February 23, 1998). "Torah scroll dedicated in Low Library". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Vadino, Dian (March 20, 1995). "Trustees approve $6M Jewish center". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Trimel, Suzanne (March 30, 2000). "The Dedication Of The Robert K. Kraft Family Center For Jewish Student Life Is Sunday, April 2, at 1 p.m." Columbia News.

- ^ Trimel, Suzanne (March 30, 2000). "The Dedication Of The Robert K. Kraft Family Center For Jewish Student Life Is Sunday, April 2, at 1 p.m." Columbia News.

- ^ Goldman, Julianna (April 3, 2000). "Dancing Presidents Help Dedicate Jewish Center". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Schwartz, Robyn (April 12, 2000). "Rabbis Inaugurate New Jewish Student Center". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Pollack, Robert E. (May 2, 1989). "In Science, Error Isn't Fraud". New York Times.

- ^ Pollack, Robert E. (February 21, 1992). "Questions and answers concerning the financial aid crisis". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ "Robert E. Pollack". John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation.

- ^ Bickley, Saara (April 16, 1993). "Faculty members receive fellowships". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ "Review of Signs of Life by Robert Pollack". Kirkus Reviews. December 1, 1993.

- ^ LANDRES, SHAWN (February 7, 1994). "Will knowledge set us free?". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Hall, Stephen S. (December 19, 1999). "Review of The Missing Moment by Robert Pollack". NY Times.

- ^ Robert Pollack (1999). The Missing Moment: How the Unconscious Shapes Modern Science. Houghton Mifflin.

- ^ Trimel, Suzanne (October 30, 2000). "Center for Study of Science and Religion Receives $100,000 Templeton Grant". Columbia University News.

- ^ Pollack, Robert E. (31 December 2000), The Faith of Biology and the Biology of Faith: Order, Meaning, and Free Will in Modern Medical Science, doi:10.7312/poll11506, ISBN 9780231529051

- ^ "Leonard Hastings Schoff Memorial Lecture Series". Columbia University Seminars. Columbia University. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ^ Pollack, Robert (2013). The faith of biology & the biology of faith: order, meaning, and free will in modern medical science (Paperback ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231115070.

- ^ "Interview: Robert Wright & Robert Pollack - Combining Science and Religion". YouTube. 25 May 2017. Retrieved January 21, 2024.

- ^ "Robert Pollack". Columbia Climate School. Columbia University.

- ^ "History of the Seminars" (PDF). Columbia University Seminars. Columbia University.

- ^ "About the University Seminars". Columbia University Seminars. Columbia University.

- ^ "2020-2021 University Seminars Directory" (PDF). Columbia University Seminars. Columbia University.

- ^ Thai Jones (2011). "Professor Anarchist". Columbia Daily Spectator.

- ^ "The University Seminars Archive". Columbia University Seminars. Columbia University.

- ^ "Rethinking Our Vision of Success".

- ^ Pollack, Robert (2016–2017). "Director's Letter" (PDF). RCSS Journal of Undergraduate Research.

- ^ "Seed Grant Award: Black Undergraduate Mentorship Program (BUMP) in Biology at Columbia". Columbia University. Office of the Provost. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ "2022-2023 Year in Review". Center for Science and Society. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- ^ Zhang, Dennis. "Robert E. Pollack". Research Cluster on Science and Subjectivity. Columbia University. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ^ "Robert E. Pollack". Center for Science and Society. Columbia University. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ^ Witkowski, Jan (12 September 2019). "How one family secured the future of a laboratory". CSHL Stories and Media. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

- ^ Mukherjee, Siddhartha (2017). The gene: an intimate history (First Scribner trade paperback ed.). New York London Toronto: Scribner. ISBN 978-1-4767-3350-0.

- ^ Fredrickson, Donald S. (1991). Asilomar and Recombinant DNA: The End of the Beginning. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Study Decision Making.

- ^ Lear, John (1978). Recombinant DNA: the untold story. New York: Crown. ISBN 0517531658.

- ^ Pollack, Robert; Cobb, Matthew (14 February 2022). "Are there any good experiments that should not be done?". PLOS Biology. 20 (2): e3001539. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3001539. PMC 8880928. PMID 35157696.

- ^ "Bridging evolutionary barriers, Robert Pollack". DNA Learning Center, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. DNAi.

- ^ "Reaction to outrage over recombinant DNA, Paul Berg". DNA Learning Center, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. DNAi.

- ^ "Biohazards in biological research : proceedings of a conference held at the Asilomar Conference Center, Pacific Grove, California, January 22-24". Wellcome Collection. Conference on Biohazards in Cancer Research.

- ^ Cobb, Matthew (2022). As gods: a moral history of the genetic age (First US ed.). New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-1541602847.

- ^ Kozubek, Jim (26 April 2018). "Modern Prometheus: Editing the Human Genome with Crispr-Cas9". Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108597104.004.

- ^ "Robert Pollack". CULPA.

- ^ "EEEBGU4321 Spring 2019 Syllabus" (PDF). Columbia Center for Science and Society.

- ^ "Robert E. Pollack". Columbia University Center for Science and Society.

- ^ Tabios, Eileen (September 24, 1980). "Officials seek to draw A&S closer into centralized planning process". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ "Columbia College Committee on Instruction". Columbia Undergraduate Admissions.

- ^ Failer, Lisa (December 2, 1982). "Profs defend core as 'timeless'". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Pollack, Robert (December 1, 1987). "No received truths, no forbidden thoughts". Columbia College Today.

- ^ Pollack, Robert (November 1, 1981). "From Theory to Praxis". Columbia College Today.

- ^ VINCIGUERRA, THOMAS (February 23, 1984). "Pollack: We need to pay more attention to 'scientific literacy'". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Magnani, Jared (November 5, 1987). "Pollack calls science necessary for the complete scholar". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Waldman, Mike (July 29, 1981). "CC starting new science course". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ "New College Course Seeks to Reduce 'Scientific Illiteracy'". Columbia University Record. September 11, 1981.

- ^ Hill, Douglas (April 15, 1982). "New dean does not like idea of 'science hum' core course". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Rhodes, Richard (October 16, 1996). How to write : advice and reflections. William Morrow & Co. ISBN 978-0688149482.

- ^ "Syllabus, SCIENCE C1002y: THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF SCIENCE-BIOLOGY". Project 2061. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- ^ Carrier, Emily (November 10, 1992). "Committee stresses innovative science". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Craig, Jeffrey (May 17, 1983). "Science Hum gets $240G donation". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ Pollack, Robert (April 1, 1995). The Theory and Practice of Science - Biology. Columbia University Archives. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Insistent Change: Columbia's Core Curriculum at 100". Columbia University Libraries. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- ^ McPhearson, Timon P.; Gill, Stuart P.D.; Pollack, Robert; Sable, Julia E. "Increasing Scientific Literacy in Undergraduate Education: A Case Study from "Frontiers of Science" at Columbia University" (PDF). Urban Systems Lab.

- ^ "Robert Pollack". CULPA.

- ^ Pollack, Robert (Feb 23, 2013). "Letter to the Editor". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ "Science as a Liberal Art". Columbia Spectator. April 5, 1983.

- ^ The Theory and Practice of Science. Columbia University Archives. 1 April 1985. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kelley, Darcy; Melnick, Don; Hughes, Ivana (April 11, 2012). "Refining the pursuit". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ "Frontiers of Science receives highest student course evaluation score since its founding - Columbia Spectator". Columbia Daily Spectator. Retrieved 2021-09-05.

- ^ "Frontiers of Science". WikiCU.

- ^ "Alexander Hamilton Medal". Columbia College Alumni Association. Columbia University. 14 December 2016.

- ^ "Annual Dinner". COLUMBIA/BARNARD HILLEL. Columbia University.

- ^ "Review of Signs of Life by Robert Pollack". Kirkus Reviews. December 1, 1993.

- ^ "Trilling and Van Doren Awards". Columbia College. Columbia University.

- ^ CRAIGLOW, ALISON (July 9, 1986). "Pollack's face graces subway walls". Columbia Spectator.

- ^ "DEAN OF COLUMBIA COMMITTED TO COEDUCATION". NY Times. November 7, 1982.

- ^ a b Katz, James C. (April 1, 1989). "Around the Quads: Robert Pollack resigns as Dean of the College". Columbia College Today.

- ^ "Class Notes: 1961". Columbia College Today. December 1, 2021.

- ^ Pollack, Robert (August 14, 2014). The Course of Nature: A Book of Drawings on Natural Selection and Its Consequences. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1499122244.

- ^ "Marya Pollack". Research Cluster on Science and Subjectivity. Retrieved 1 July 2023.