This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2012) |

Rhabdoviridae is a family of negative-strand RNA viruses in the order Mononegavirales.[1] Vertebrates (including mammals and humans), invertebrates, plants, fungi and protozoans serve as natural hosts.[2][3][4] Diseases associated with member viruses include rabies encephalitis caused by the rabies virus, and flu-like symptoms in humans caused by vesiculoviruses. The name is derived from Ancient Greek rhabdos, meaning rod, referring to the shape of the viral particles.[5] The family has 40 genera, most assigned to three subfamilies.[6]

| Rhabdoviridae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Vesicular stomatitis Indiana virus (VSV), the prototypical rhabdovirus | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Negarnaviricota |

| Class: | Monjiviricetes |

| Order: | Mononegavirales |

| Family: | Rhabdoviridae |

| Genera | |

Structure

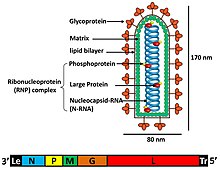

editThe individual virus particles (virions) of rhabdoviruses are composed of RNA, protein, carbohydrate and lipid. They have complex bacilliform or bullet-like shapes. All these viruses have structural similarities and have been classified as a single family.[7]

The virions are about 75 nm wide and 180 nm long.[2] Rhabdoviruses are enveloped and have helical nucleocapsids and their genomes are linear, around 11–15 kb in length.[5][2] Rhabdoviruses carry their genetic material in the form of negative-sense single-stranded RNA. They typically carry genes for five proteins: large protein (L), glycoprotein (G), nucleoprotein (N), phosphoprotein (P), and matrix protein (M).[8] The sequence of these protein genes from the 3 'end to the 5' end in the genome is N–P–M–G–L.[9] Every rhabdoviruses encode these five proteins in their genomes. In addition to these proteins, many rhabdoviruses encode one or more proteins.[10] The first four genes encode major structural proteins that participate in the structure of the virion envelope.[9]

The matrix protein (M) constitutes a layer between the virion envelope and the nucleocapsid core of the rhabdovirus.[10] In addition to the functions about virus assembly, morphogenesis and budding off enveloped from the host plasma membrane, additional functions such as the regulation of RNA synthesis, affecting the balance of replication and transcription products was found, making reverse genetics experiments with rabies virus, a member of the family Rhabdoviridae.[11] The large (L) protein has several enzymatic functions in viral RNA synthesis and processing.[8] The L gene encodes this L protein, which contains multiple domains. In addition to RNA synthesis, it is thought to be involved in methyl capping and polyadenylation activity.[9]

P protein plays important and multiple roles during transcription and replication of the RNA genome. The multifunctional P protein is encoded by the P gene. P protein acts as a non-catalytic cofactor of large protein polymerase. It is binding to N and L protein. P protein has two independent binding regions. By forming N-P complexes, it can keep the N protein in the form suitable for specific encapsulation. P protein interferes with the host's innate immune system through inhibition of the activities of interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) and signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1), thus eliminating the cellular type 1 interferon pathway. Also, P protein acts as an antagonist against antiviral PML function.[12][13]

Rhabdoviruses that infect vertebrates (especially mammals and fishes), plants, and insects are usually bullet-shaped.[14] However, in contrast to paramyxoviruses, rhabdoviruses do not have hemagglutinating and neuraminidase activities.[14]

Transcription

editTranscriptase of rhabdovirus is composed of 1 L and 3 P proteins. Transcriptase components are always present in the complete virion to permit rhabdoviruses to begin transcription immediately after entry.[citation needed]

The rhabdovirus transcriptase proceeds in a 3' to 5' direction on the genome and the transcription terminates randomly at the end of protein sequences. For example, if a transcription finishes at the end of M sequence; leader RNA and N, P and M mRNAs are formed separately from each other.[citation needed]

Also, mRNAs accumulate according to the order of protein sequences on the genome, solving the logistics problem in the cell. For example, N protein is necessary in high quantities for the virus, as it coats the outside of the replicated genomes completely. Since the N protein sequence is located at the beginning of the genome (3' end) after the leader RNA sequence, mRNAs for N protein can always be produced and accumulate in high amounts with every termination of transcription. After the transcription processes, all of the mRNAs are capped at the 5' end and polyadenylated at the 3' end by L protein.

This transcription mechanism thus provides mRNAs according to the need of the viruses.[10]: 173–184

Translation

editThe virus proteins translated on free ribosomes but G protein is translated by the rough endoplasmic reticulum. This means G protein has a signal peptide on its mRNA's starting codes. Phosphoproteins (P) and glycoprotein (G) undergo post-translational modification. Trimers of P protein are formed after phosphorylation by kinase activity of L protein. The G protein is glycosylated in the rough endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi complex.[10]: 180

Replication

editViral replication is cytoplasmic. The replication cycle is the same for most rhabdoviruses. All components required for early transcription and the nucleocapsid are released to the cytoplasm of the infected cell after the first steps of binding, penetration and uncoating take place.[9] Entry into the host cell is achieved by attachment of the viral G glycoproteins to host receptors, which mediates clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Replication follows the negative stranded RNA virus replication model. Negative stranded RNA virus transcription, using polymerase stuttering is the method of transcription. The virus exits the host cell by budding, and tubule-guided viral movement. Transmission routes are zoonosis and bite.[5][2]

Replication of many rhabdoviruses occurs in the cytoplasm, although several of the plant infecting viruses replicate in the nucleus.[15] The rhabdovirus matrix (M) protein is very small (~20–25 kDa) however plays a number of important roles during the replication cycle of the virus. These proteins of rhabdoviruses constitute major structural components of the virus and they are multifunctional proteins and required for virus maturation and viral budding process that also regulate the balance of virus RNA synthesis by shifting synthesis from transcription to replication.[16] In order for replication, both the L and P protein must be expressed to regulate transcription.[17] Phosphoprotein (P) also plays a crucial role during replication, as N-P complexes, rather than N alone, are necessary for appropriate and selective encapsidation of viral RNA. Therefore, replication is not possible after infection until the primary transcription and translation produce enough N protein.[18]

The L protein has a lot of enzymatic activity such as RNA replication, capping mRNAs phosphorylation of P. L protein gives feature in about replication in cytoplasm.[17] Transcription results in five monocistronic mRNAs being produced because the intergenic sequences act as both termination and promoter sequences for adjacent genes. This type of transcription mechanism is explained by stop-start model (stuttering transcription). Owing to stop-start model, the large amounts of the structural proteins are produced. According to this model, the virus-associated RNA polymerase starts firstly the synthesis of leader RNA and then the five mRNA which will produce N, P, M, G, L proteins, respectively. After the leader RNA was produced, the polymerase enzyme reinitiates virion transcription on N gene and proceeds its synthesis until it ends 3′ end of the chain. Then, the synthesis of P mRNAs are made by same enzyme with new starter sinyal. These steps continue until the enzyme arrives the end of the L gene. During transcription process, the polymerase enzyme may leave the template at any point and then bound just at the 3′ end of the genome RNA to start mRNA synthesis again. This process will results concentration gradient of the amount of mRNA based on its place and its range from the 3′ end. In the circumstances, the amounts of mRNA species change and will be produced N>P>M>G>L proteins.[19] During their synthesis the mRNAs are processed to introduce a 5' cap and a 3’ polyadenylated tail to each of the molecules. This structure is homologous to cellular mRNAs and can thus be translated by cellular ribosomes to produce both structural and non-structural proteins.

Genomic replication requires a source of newly synthesized N protein to encapsidate the RNA. This occurs during its synthesis and results in the production of a full-length anti-genomic copy. This in turn is used to produce more negative-sense genomic RNA. The viral polymerase is required for this process, but how the polymerase engages in both mRNA synthesis and genomic replication is not well understood.

Replication characteristically occurs in an inclusion body within the cytoplasm, from where they bud through various cytoplasmic membranes and the outer membrane of the cell. This process results in the acquisition of the M + G proteins, responsible for the characteristic bullet- shaped morphology of the virus.

Classification

editClades

editThese viruses fall into four groups based on the RNA polymerase gene.[20] The basal clade appears to be novirhabdoviruses, which infect fish. Cytorhabdoviruses and the nucleorhabdoviruses, which infect plants, are sister clades. Lyssaviruses form a clade of their own which is more closely related to the land vertebrate and insect clades than to the plant viruses. The remaining viruses form a number of highly branched clades and infect arthropods and land vertebrates.

A 2015 analysis of 99 species of animal rhabdoviruses found that they fell into 17 taxonomic groupings, eight – Lyssavirus, Vesiculovirus, Perhabdovirus, Sigmavirus, Ephemerovirus, Tibrovirus, Tupavirus and Sprivivirus – which were previously recognized.[21] The authors proposed seven new taxa on the basis of their findings: "Almendravirus", "Bahiavirus", "Curiovirus", "Hapavirus", "Ledantevirus", "Sawgravirus" and "Sripuvirus". Seven species did not group with the others suggesting the need for additional taxa.

Proposed classifications

editAn unofficial supergroup – "Dimarhabdovirus" – refers to the genera Ephemerovirus and Vesiculovirus.[22] A number of other viruses that have not been classified into genera also belong to this taxon. This supergroup contains the genera with species that replicate in both vertebrate and invertebrate hosts and have biological cycles that involve transmission by haematophagous dipterans (bloodsucking flies).

Prototypical rhabdoviruses

editThe prototypical and best studied rhabdovirus is vesicular stomatitis Indiana virus. It is a preferred model system to study the biology of rhabdoviruses, and mononegaviruses in general. The mammalian disease rabies is caused by lyssaviruses, of which several have been identified.

Rhabdoviruses are important pathogens of animals and plants. Rhabdoviruses are transmitted to hosts by arthropods, such as aphids, planthoppers, leafhoppers, black flies, sandflies, and mosquitoes.

In September 2012, researchers writing in the journal PLOS Pathogens described a novel species of rhabdovirus, called Bas-Congo virus (BASV), which was discovered in a blood sample from a patient who survived an illness that resembled hemorrhagic fever.[20] No cases of BASV have been reported since its discovery and it is uncertain if BASV was the actual cause of the patient's illness.[23]

In 2015 two novel rhabdoviruses, Ekpoma virus 1 and Ekpoma virus 2, were discovered in samples of blood from two healthy women in southwestern Nigeria. Ekpoma virus 1 and Ekpoma virus 2 appear to replicate well in humans (viral load ranged from ~45,000 - ~4.5 million RNA copies/mL plasma) but did not cause any observable symptoms of disease.[24] Exposure to Ekpoma virus 2 appears to be widespread in certain parts of Nigeria where seroprevalence rates are close to 50%.[24]

Taxonomy

editIn the Alpharhabdovirinae subfamily, the following genera are recognized:[6]

- Almendravirus

- Alphanemrhavirus

- Alphapaprhavirus

- Alpharicinrhavirus

- Arurhavirus

- Barhavirus

- Caligrhavirus

- Curiovirus

- Ephemerovirus

- Hapavirus

- Ledantevirus

- Lostrhavirus

- Lyssavirus

- Merhavirus

- Mousrhavirus

- Ohlsrhavirus

- Perhabdovirus

- Sawgrhavirus

- Sigmavirus

- Sprivivirus

- Sripuvirus

- Sunrhavirus

- Tibrovirus

- Tupavirus

- Vesiculovirus

- Zarhavirus

The genera of the other subfamilies are as follows:[6]

- Betarhabdovirinae

- Alphanucleorhabdovirus (currently; see nucleorhabdovirus)

- Betanucleorhabdovirus (currently; see nucleorhabdovirus)

- Cytorhabdovirus

- Dichorhavirus

- Gammanucleorhabdovirus (currently; see nucleorhabdovirus)

- Varicosavirus

- Gammarhabdovirinae

The following genera are unassigned to the a subfamily:[6]

- Alphacrustrhavirus

- Alphadrosrhavirus

- Alphahymrhavirus

- Betahymrhavirus

- Betanemrhavirus

- Betapaprhavirus

- Betaricinrhavirus

In addition to the above, there are a large number of rhabdo-like viruses that have not yet been officially classified by the ICTV.[5]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Walker PJ, Blasdell KR, Calisher CH, Dietzgen RG, Kondo H, Kurath G, et al. (April 2018). "ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Rhabdoviridae". The Journal of General Virology. 99 (4): 447–448. doi:10.1099/jgv.0.001020. hdl:10871/31776. PMID 29465028.

- ^ a b c d "Viral Zone". ExPASy. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ Bird, R.G.; McCaul, T.F. (March 1976). "The rhabdoviruses of Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba invadens". Annals of Tropical Medicine & Parasitology. 70 (1): 81–93. doi:10.1080/00034983.1976.11687098. PMID 178279.

- ^ Fan Mu,Bo Li,Shufen Cheng,Jichun Jia,Daohong Jiang,Yanping Fu,Jiasen Cheng,Yang Lin,Tao Chen,Jiatao Xie (2021). Nine viruses from eight lineages exhibiting new evolutionary modes that co-infect a hypovirulent phytopathogenic fungus. Plos Pathogens.

- ^ a b c d "Family: Rhabdoviridae | ICTV". www.ictv.global.

- ^ a b c d "Virus Taxonomy: 2020 Release". International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). March 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ Jackson, A. O.; Francki, R. I. B.; Zuidema, Douwe (1987). "Biology, Structure, and Replication of Plant Rhabdoviruses". The Rhabdoviruses. pp. 427–508. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-7032-1_10. ISBN 978-1-4684-7034-5.

- ^ a b Ogino M, Ito N, Sugiyama M, Ogino T (May 2016). "The Rabies Virus L Protein Catalyzes mRNA Capping with GDP Polyribonucleotidyltransferase Activity". Viruses. 8 (5): 144. doi:10.3390/v8050144. PMC 4885099. PMID 27213429.

- ^ a b c d Assenberg, R.; Delmas, O.; Morin, B.; Graham, S.C.; De Lamballerie, X.; Laubert, C.; Coutard, B.; Grimes, J.M.; Neyts, J.; Owens, R.J.; Brandt, B.W.; Gorbalenya, A.; Tucker, P.; Stuart, D.I.; Canard, B.; Bourhy, H. (August 2010). "Genomics and structure/function studies of Rhabdoviridae proteins involved in replication and transcription" (PDF). Antiviral Research. 87 (2): 149–161. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.02.322. PMID 20188763. S2CID 8840157.

- ^ a b c d Carter JB, Saunders VA (2007). Virology: Principles and Applications. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-02386-0. OCLC 124160564.

- ^ Finke S, Conzelmann KK (November 2003). "Dissociation of rabies virus matrix protein functions in regulation of viral RNA synthesis and virus assembly". Journal of Virology. 77 (22): 12074–12082. doi:10.1128/JVI.77.22.12074-12082.2003. PMC 254266. PMID 14581544.

- ^ Wang L, Wu H, Tao X, Li H, Rayner S, Liang G, Tang Q (January 2013). "Genetic and evolutionary characterization of RABVs from China using the phosphoprotein gene". Virology Journal. 10 (1): 14. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-10-14. PMC 3548735. PMID 23294868.

- ^ Okada K, Ito N, Yamaoka S, Masatani T, Ebihara H, Goto H, et al. (September 2016). Lyles DS (ed.). "Roles of the Rabies Virus Phosphoprotein Isoforms in Pathogenesis". Journal of Virology. 90 (18): 8226–37. doi:10.1128/JVI.00809-16. PMC 5008078. PMID 27384657.

- ^ a b Nicholas H (2007). Fundamentals of Molecular Virology. England: Wiley. pp. 175–187.

- ^ "Genus: Alphanucleorhabdovirus - Rhabdoviridae - Negative-sense RNA Viruses - ICTV". talk.ictvonline.org. Archived from the original on 23 June 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ^ Graham SC, Assenberg R, Delmas O, Verma A, Gholami A, Talbi C, et al. (December 2008). "Rhabdovirus matrix protein structures reveal a novel mode of self-association". PLOS Pathogens. 4 (12): e1000251. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000251. PMC 2603668. PMID 19112510.

- ^ a b Acheson NH (2011). Fundamentals of Molecular Virology (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-0470900598.

- ^ Finke S, Conzelmann KK (November 2003). "Dissociation of rabies virus matrix protein functions in regulation of viral RNA synthesis and virus assembly". Journal of Virology. 77 (22): 12074–82. doi:10.1128/JVI.77.22.12074-12082.2003. PMC 254266. PMID 14581544.

- ^ Maclachlan NJ, Dubovi EJ, eds. (2011). "Rhabdoviridae". Fenner's Veterinary Virology. pp. 327–41. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-375158-4.00018-3. ISBN 978-0-12-375158-4.

- ^ a b Grard G, Fair JN, Lee D, Slikas E, Steffen I, Muyembe JJ, et al. (September 2012). "A novel rhabdovirus associated with acute hemorrhagic fever in central Africa". PLOS Pathogens. 8 (9): e1002924. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002924. PMC 3460624. PMID 23028323.

- ^ Walker PJ, Firth C, Widen SG, Blasdell KR, Guzman H, Wood TG, et al. (February 2015). "Evolution of genome size and complexity in the rhabdoviridae". PLOS Pathogens. 11 (2): e1004664. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004664. PMC 4334499. PMID 25679389.

- ^ Bourhy H, Cowley JA, Larrous F, Holmes EC, Walker PJ (October 2005). "Phylogenetic relationships among rhabdoviruses inferred using the L polymerase gene". The Journal of General Virology. 86 (Pt 10): 2849–2858. doi:10.1099/vir.0.81128-0. PMID 16186241.

- ^ Branco LM, Garry RF (3 December 2018). "Bas-Congo virus - not an established pathogen". Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ a b Stremlau MH, Andersen KG, Folarin OA, Grove JN, Odia I, Ehiane PE, et al. (March 2015). Rupprecht CE (ed.). "Discovery of novel rhabdoviruses in the blood of healthy individuals from West Africa". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 9 (3): e0003631. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003631. PMC 4363514. PMID 25781465.

Further reading

edit- Rose JK, Whitt MA (2001). "Rhabdoviridae: The viruses and their replication". In Knipe DM, Howley PM (eds.). Field's Virology. Vol. 1 (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1221–44. ISBN 978-0781718325.

- Wagner RR, ed. (1987). The Rhabdoviruses. Plenum Press. ISBN 978-0-306-42453-3.