Raphael Gamaliel Warnock[1] (/ˈrɑːfiɛl ˈwɔːrnɒk/ RAH-fee-el WOR-nok; born July 23, 1969) is an American Baptist pastor and politician serving as the junior United States senator from Georgia since 2021. A member of the Democratic Party, Warnock has been the senior pastor of Atlanta's Ebenezer Baptist Church since 2005.[2][3]

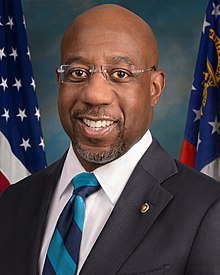

Raphael Warnock | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, 2021 | |

| United States Senator from Georgia | |

| Assumed office January 20, 2021 Serving with Jon Ossoff | |

| Preceded by | Kelly Loeffler |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Raphael Gamaliel Warnock July 23, 1969 Savannah, Georgia, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Oulèye Ndoye

(m. 2016; div. 2020) |

| Children | 2 |

| Residence(s) | Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. |

| Education | Morehouse College (BA) Union Theological Seminary (MDiv, MPhil, PhD) |

| Occupation |

|

| Website | Senate website |

| Religious life | |

| Religion | Christian |

| Denomination | Baptist (Progressive National Baptist Convention) |

| Church | Ebenezer Baptist Church |

| Senior posting | |

| Post | Senior pastor (2005–present) |

Warnock was the senior pastor of Douglas Memorial Community Church from 2001 to 2005.[4] He came to prominence in Georgia politics as a leading activist in the campaign to expand Medicaid in the state under the Affordable Care Act. He was the Democratic nominee in the 2020 United States Senate special election in Georgia, and defeated incumbent Republican Kelly Loeffler in the runoff election.[5] He was reelected to a full term in 2022, defeating Republican nominee Herschel Walker.

Warnock and Ossoff are the first Democrats elected to the U.S. Senate from Georgia since Zell Miller in 2000.[6][7] Warnock is the first African American to represent Georgia in the Senate, and the first Black Democrat elected to the Senate from a Southern state.[8][9][10]

Early life and education

editWarnock was born in Savannah, Georgia, on July 23, 1969.[11] He grew up in public housing as the eleventh of twelve children born to Verlene and Jonathan Warnock, both Pentecostal pastors.[12][13] His father served in the U.S. Army during World War II, where he learned automobile mechanics and welding, and subsequently opened a small car restoration business where he restored junked cars for resale.[14] His mother picked cotton and tobacco in the summers in Waycross, Georgia, as a teenager and became a pastor.[15]

Warnock graduated from Sol C. Johnson High School in 1987,[16] and having wanted to follow in the footsteps of Martin Luther King Jr., attended Morehouse College, from which he graduated cum laude in 1991 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in psychology.[17][18] He credits his participation in the Upward Bound program for making him college-ready, as he was able to enroll in early college courses through Savannah State University.[16][18] He then earned Master of Divinity, Master of Philosophy, and Doctor of Philosophy degrees from Union Theological Seminary, a school affiliated with Columbia University.[19][20][14]

Religious work

editWarnock began his ministry as an intern and licentiate at the Sixth Avenue Baptist church in Birmingham, Alabama,[22] under the civil rights movement leader John Thomas Porter.[22][23] In the 1990s, he served as youth pastor and then assistant pastor at Abyssinian Baptist Church in New York.[24][25] While Warnock was pastor at Abyssinian, the church declined to hire workfare recipients as part of organized opposition to then-mayor Rudy Giuliani's workfare program.[26] The church also hosted Fidel Castro on October 22, 1995, while Warnock was youth pastor. There is no evidence Warnock was involved in that decision. During the 2020–21 United States Senate special election in Georgia, his campaign refused to say whether Warnock attended the event.[27]

In January 2001, Warnock was elected senior pastor of Douglas Memorial Community Church in Baltimore, Maryland.[28][29] He and an assistant minister were arrested and charged with obstructing a 2002 police investigation into suspected child abuse at a summer camp the church ran. The police report called Warnock "extremely uncooperative and disruptive". Warnock had demanded that the counselors have lawyers present when being interviewed by police.[30] The charges were later dropped with the deputy state's attorney's acknowledgment that it had been a "miscommunication", adding that Warnock had aided the investigation and that prosecution would be a waste of resources.[31][32] Warnock said he was merely asserting that lawyers should be present during the interviews[33] and that he had intervened to ensure that an adult was present while a juvenile suspect was being questioned.[34] Warnock stepped down as the church's senior pastor in 2005.[4]

On Father's Day 2005, Warnock was named senior pastor of the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, Georgia, Martin Luther King Jr.'s former congregation;[35] he is the fifth and the youngest person to serve as Ebenezer's senior pastor since its founding.[16][36][37] He has continued in the post while serving in the Senate.[38][39]

As pastor, Warnock advocated for clemency for Troy Davis, who was executed in 2011.[40] In 2013, he delivered the benediction at the public prayer service at the second inauguration of Barack Obama.[41] After Fidel Castro died in 2016, Warnock told his church to pray for the Cuban people, calling Castro's legacy "complex, kind of like America's legacy is complex".[27] In March 2019, Warnock hosted an interfaith meeting on climate change at his church, featuring Al Gore and William Barber II.[42] He presided at Representative John Lewis's funeral at Ebenezer Church in July 2020.[43][21]

On Easter Sunday 2021, Warnock's Twitter account tweeted, "The meaning of Easter is more transcendent than the resurrection of Jesus Christ. Whether you are a Christian or not, through a commitment to helping others we are able to save ourselves." Some conservative Christians and political commentators criticized the tweet, including Benjamin Watson, Allie Beth Stuckey, and Jenna Ellis, who called it "heretical". The tweet was deleted that afternoon, with a spokesperson for Warnock saying, "the tweet was posted by staff and was not approved" but declining to say whether it reflected Warnock's beliefs.[44][45]

Political activism

editWarnock came to prominence in Georgia politics as a leader in the campaign to expand Medicaid in the state.[46] In 2013, he wrote an editorial for the Atlanta Journal Constitution that criticized Governor Nathan Deal for not supporting an integrated prom at the Wilcox County High School.[47] In March 2014, Warnock led a sit-in at the Georgia State Capitol to press state legislators to accept the expansion of Medicaid offered by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.[48][49] He and other leaders were arrested during the protest.[48][50] Warnock also actively campaigned for Georgia Democrats to increase outreach to low-income communities.[51] In 2015, Warnock considered running in the 2016 election for the United States Senate seat held by Johnny Isakson as a member of the Democratic Party.[52] He opted not to run.[53][54]

From June 2017 to January 2020, Warnock chaired the New Georgia Project, a nonpartisan organization focused on increasing voter registration.[55][36]

Warnock supports expanding the Affordable Care Act and has called for the passage of the John Lewis Voting Rights Act.[56][46] He also supports increasing COVID-19-relief funding.[57] A proponent of abortion rights and gay marriage, he has been endorsed by Planned Parenthood.[58][59] He opposes the concealed carry of firearms, saying that religious leaders do not want guns in places of worship.[60] Warnock has long opposed the death penalty.[61]

U.S. Senate

editElections

edit2020–21 Special

editIn January 2020, Warnock decided to run in the 2020 special election for the United States Senate seat held by Kelly Loeffler, who was appointed after Johnny Isakson's resignation.[62] Stacey Abrams encouraged him to run and coordinated his support from Democratic leadership.[63] He was endorsed by Democratic senators Chuck Schumer, Cory Booker, Sherrod Brown, Kirsten Gillibrand, Jeff Merkley, Chris Murphy, Bernie Sanders, Brian Schatz, and Elizabeth Warren; the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee, Stacey Abrams, and former presidents Barack Obama and Jimmy Carter.[64][36][65][66][67] Several players of the Atlanta Dream, a WNBA team Loeffler co-owned at the time, wore shirts endorsing Warnock in response to controversial comments Loeffler made about the Black Lives Matter movement.[68]

The closing argument of Warnock's campaign focused on the $2,000 stimulus payments that he and Ossoff would approve if they were elected, giving Democrats a Senate majority.[69][70]

In the January 5 runoff election, Warnock defeated Loeffler with 51.04% of the vote. With this victory, he became the first African American to represent Georgia in the Senate, the first Black Democratic U.S. senator elected in the South, and the first Black Democrat elected to the Senate by a former state of the Confederacy.[8][9][10][71] Warnock and Ossoff are the first Democrats elected to the U.S. Senate from Georgia since Zell Miller in 2000.[6][7] On January 7, Loeffler conceded.[72] The election result was certified on January 19.[73]

2022

editOn January 27, 2021, Warnock announced that he would seek election to a full term in 2022.[74]

Since no candidate received a majority of the vote in the general election on November 8, 2022, Warnock faced Walker in a runoff election on December 6, and won.[75][76] He became the first Georgia Democrat to win reelection to the Senate since Sam Nunn in 1990[77] and the first Deep South Democrat to win reelection to the Senate since Mary Landrieu of Louisiana in 2008.[78]

Tenure

editOn January 20, 2021, Warnock was sworn into the United States Senate in the 117th Congress by Vice President Kamala Harris.[79][80][81]

On February 13, 2021, Warnock voted to convict former president Donald Trump of inciting the January 6 United States Capitol attack.[82][83]

On March 5, 2021, he co-sponsored an amendment to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour, along with 29 other Democratic and independent senators.[84]

On March 17, 2021, he delivered his first speech on the Senate floor, in support of the passage of the For the People Act and the John Lewis Voting Rights Act.[85]

In January 2022, when former U.S. senator Johnny Isakson died, Warnock introduced a Senate resolution to honor Isakson, which was enacted with bipartisan support, while commenting that Isakson was "a patriot, a public servant" who "knew how to show up for people".[86][87]

In October 2022, a bill by Warnock and Senator Jon Ossoff was enacted into law, naming a United States Post Office building in Atlanta, Georgia after John Lewis, who was a U.S. representative for Atlanta until his death in 2020.[88][89]

In September 2023, Warnock was the only Democrat on the Senate Banking Committee to vote against the Secure and Fair Enforcement Regulation (SAFER) Banking Act, which provides a safe harbor for legal state-level marijuana dispensaries and growers to access federally regulated banks.[90]

Committee assignments

editWarnock has been assigned to the following committees for the 117th United States Congress:[91]

- Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry

- Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation

- Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs

- Congressional Joint Economic Committee

- Special Committee on Aging

Caucuses

editPolitical positions

editIn April 2021, Politico reported that Warnock, as a U.S. senator, had embraced "a progressive agenda".[94] As of December 2022, Warnock had voted in line with President Joe Biden's stated position 96.5% of the time.[95]

According to website GovTrack, for Warnock's Senate term from January 2021 to January 2023, he was ranked "most politically right" of all Senate Democrats in the 117th Congress, and was noted to have joined "bipartisan bills the 2nd most often" of all Senate Democrats in the 117th Congress.[96]

Abortion

editWarnock has described himself as a "pro-choice pastor".[97][98]

In December 2020, during Warnock's Senate campaign, a group of 25 Black ministers wrote him an open letter asking him to reconsider his abortion stance, calling it "contrary to Christian teachings" and saying abortion disproportionately affects African Americans. The Warnock campaign responded with a statement, writing that "Warnock believes a patient's room is too small a place for a woman, her doctor, and the US government and that these are deeply personal health care decisions – not political ones."[99]

Warnock called the June 2022 overturning of Roe v. Wade "misguided" and "devastating for women and families in Georgia and nationwide."[100][101][102]

Agriculture

editWarnock was the main sponsor of S.278 - Emergency Relief for Farmers of Color Act of 2021.[103] The bill would aid historically disaffected minority groups in the agriculture sector.[104]

Warnock worked with Senator Tommy Tuberville to reduce barriers to trade for peanut exports, to assist peanut farmers in Georgia.[105][106][107]

Capital punishment and criminal justice

editWarnock opposes the death penalty.[108] He unsuccessfully attempted to stop death row inmate Troy Davis's execution.[108]

Defense

editAfter President Joe Biden recommended in March 2022 that the Air National Guard's Combat Readiness Training Center in Savannah, Georgia, be closed, Warnock was one of several Georgia lawmakers to oppose the move, calling Biden's recommendation "bad for Savannah and bad for our national security"; the Appropriations subcommittee of the House of Representatives rejected the recommendation in June 2022.[109]

Warnock supported the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022, which provides funding for defense purposes, saying: "Georgia is an important military state ... Fort Stewart will get an upgrade in its energy plant to the tune of $22 million. There is also $100 million in this bill for barracks at Fort Stewart. We have to make sure that those who we ask to serve have what they need in order to serve".[110] The barracks are slated to house over 370 soldiers.[111]

Economy and infrastructure

editWarnock worked together with Senator Ted Cruz to introduce legislation to prioritize the building of Interstate 14 connecting Augusta, Macon, and Columbus in Georgia to Texas; Warnock said the interstate would be "helpful for our military installations" and "for the economy in this region".[112] The prioritization was ultimately approved within the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act that passed in November 2021, with the interstate slated to also pass through Midland–Odessa, Texas; Alexandria, Louisiana; Laurel, Mississippi; and Montgomery, Alabama.[113]

Warnock has helped to obtain millions in funding for the Port of Savannah and for the new Northeast Georgia Inland Port in Hall County, Georgia.[114][115]

Warnock supports raising the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour.[116][117]

Environment

editIn 2022, Warnock emphasized the importance of the national climate bill within his campaign.[118] Warnock referenced the contaminated water and air in Black and brown communities, such as the water crises in Jackson, Mississippi, and Flint, Michigan, and the burden placed on low-income families that pay a larger portion of their income on utilities.[118]

After attending a groundbreaking at Hyundai's electric vehicle plant in Savannah, Georgia alongside Brian Kemp, Warnock told reporters that climate policy is a "moral" issue.[119] He said, "I've also put forward a lot of legislation focused on creating a green energy future, everything from electric vehicles to electric batteries being manufactured in the state to investing in solar manufacturing".[119]

Warnock was a cosponsor of the Recycling Infrastructure and Accessibility Act of 2022,[120] a bipartisan bill that "requires the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to establish a pilot grant program for improving recycling accessibility in communities".[121]

Gun control

editWarnock received a grade of "F" from the NRA Political Victory Fund during his Senate campaign.[122] The NRA accused him of supporting the criminalization of private gun transfers and banning standard issue magazines, and endorsed Loeffler.[123] In 2014, Warnock gave a sermon in which he criticized Georgia's gun laws, saying that "somebody decided that they had the bright idea to pass a piece of legislation that would allow guns and concealed weapons to be carried in churches. Have you ever been to a church meeting?... Whoever thought of that had never been to a church meeting."[124]

Healthcare

editIn October 2021, Warnock and Ossoff said that they had acquired federal funding under the American Rescue Plan for health centers across Georgia, including two in Macon and four in Albany, each of which received between $500,000 to $1,100,000.[125][126] Reacting to this, Warnock affirmed his support for the American Rescue Plan, saying: "We must continue to do all we can to provide support and funding to our health care infrastructure and workers on the front lines of this pandemic."[125]

A bipartisan bill on maternal health by Warnock and Senator Marco Rubio was incorporated into a $1.5 trillion federal spending package that passed Congress in March 2022.[127] Warnock's bill allocated $50 million for integrated healthcare services grants, $45 million to innovation grants, $25 million for training of healthcare workers, and approval of a study on how to teach health professionals to reduce discrimination.[127] Warnock said, "Georgia is dead last when it comes to women and their access to healthcare" and that the bill's aim was "to make sure that when women are trying to bring a child in this world, they don't have to do so with one foot in the grave".[127]

In August 2022, the Senate passed the Inflation Reduction Act, which included two proposals by Warnock: a $2,000 annual limit on prescription drug costs for seniors on Medicare, and a $35 monthly limit on insulin costs for people on Medicare.[128] Republican lawmakers removed a third proposal by Warnock that would have imposed a $35 monthly limit on out-of-pocket insulin costs for people on private insurance.[128]

Immigration

editWarnock criticized Trump's "shithole countries" comment in 2018 and his subsequent signing of a proclamation honoring Martin Luther King Jr., saying, "I would argue that a proclamation without an apology is hypocrisy. There is no redemption without repentance and the president of the United States needs to repent."[129]

Warnock also has supported keeping Title 42 expulsions, saying, "We need assurances that we have security at the border and that we protect communities on this side of the border."[130]

LGBTQ rights

editWarnock was endorsed by the Human Rights Campaign in 2020 and 2022 for his views on LGBTQ rights.[131][132] He supports the Equality Act, which would prohibit discrimination based on gender identity and sexual orientation.[133] Warnock also supported and cosponsored the Respect for Marriage Act, which would codify same-sex and interracial marriages, but was absent for the final vote due to campaigning.[134][135]

Supreme Court

editWarnock twice declined to answer when asked whether he supported "packing the Supreme Court" by adding additional justices during a December 2020 debate.[136]

Veterans and military families

editIn June 2021, Warnock and Ossoff assisted six Georgia organizations that work to reduce veteran homelessness by obtaining between $375,000 to $500,000 of federal funds for each organization, using funds from the Department of Labor's Homeless Veterans' Reintegration Program, which are intended to help the veterans find jobs.[137][138]

In September 2021, Warnock worked together with Senator Cindy Hyde-Smith to introduce legislation designating September 19 to 25 as Gold Star Families Remembrance Week nationwide, to honor sacrifices made by families of servicemen who died serving the United States; the legislation passed the Senate unanimously.[139]

In November 2021, a bill of Warnock's was enacted that approved a government study into whether there were racial disparities in benefits provided by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs.[140]

Voting rights

editIn his maiden speech on the U.S. Senate floor, Warnock said one of his primary goals upon assuming office was to oppose voting restrictions and support federal voting reforms.[141] He has said that passing legislation to expand voting rights is important enough to end the Senate filibuster.[94][142]

On March 17, 2021, Warnock said in a Senate floor speech that voting rights were under attack at a rate not seen since the Jim Crow era.[143][144] On April 20, 2021, Warnock and voting rights activist Stacey Abrams testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee in favor of passing the John Lewis Voting Rights Act and For the People Act. He was again critical of the new election laws passed in his home state, calling it a "full-fledged assault on voting rights, unlike anything we seen since the era of Jim Crow."[145] He is not opposed to voter ID laws, but criticizes them when they discriminate against certain groups.[146][147]

Welfare

editWarnock opposed New York mayor Rudy Giuliani's workfare reforms while he was assistant pastor at Abyssinian Baptist Church. In 1997, he told The New York Times, "We are worried that workfare is being used to displace other workers who receive respectable compensation... We are concerned that poor people are being put into competition with other poor people, and in that respect, we think workfare is a hoax".[148]

Israeli-Palestinian conflict

editWarnock has expressed a range of views on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. He has criticized Israel's actions, particularly in a May 2018 sermon where he discussed Israel's shooting of nonviolent Palestinian protesters, comparing the Palestinian cause to the Black Lives Matter movement. Warnock emphasized the struggle for human dignity and the Palestinians' right to self-determination, while also advocating for a two-state solution where "all of God's children can live together".[149]

In 2019, after a visit to Israel and the West Bank, Warnock signed a statement with other clergy that was critical of Israel's military occupation and settlement expansion in the West Bank. This statement compared the West Bank's heavy militarization to apartheid South Africa's occupation of Namibia, highlighting concerns about the viability of a two-state solution given these conditions.[150]

Warnock reversed course on some of these positions during his Senate campaign in November 2020, calling the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement against Israel "anti-Semitic" and a refusal to acknowledge Israel's right to exist. He has said that he does not believe Israel is an apartheid state and recognizes Israel's significance as a democracy in the Middle East and its importance as America's partner in the region. Warnock has also expressed a commitment to working toward ensuring Iran does not obtain a nuclear weapon and has voiced his opposition to conditioning U.S. assistance to Israel.[149]

In October 2023, Warnock publicly condemned Hamas's acts of violence against Israel at the start of Israel-Hamas War. In a statement, he called the violence "heinous" and emphasized the importance of seeking a "lasting peace grounded in justice and human dignity for all of God's creatures."[151]

In February 2024, Warnock delivered a Senate speech emphasizing American leadership in achieving Israeli-Palestinian peace. He called for a negotiated ceasefire in the Israel-Hamas conflict, the release of hostages, and opening humanitarian corridors to aid Gaza, and underscored the need for a two-state solution based on peace, security, and self-determination for both peoples.[152]

In March 2024, Warnock was one of 19 Democratic senators to sign a letter to the Biden administration urging the U.S. to recognize a "nonmilitarized" Palestinian state after the war in Gaza.[153]

In November 2024, Warnock voted for all three Israel-related measures proposed by Bernie Sanders: to block sales to Israel of JDAMS, tank rounds, and mortar rounds. The measures would have blocked approximately $20 billion in U.S. arms sales to Israel.[154][155]

Personal life

editWarnock lives in Atlanta.[156] He married Oulèye Ndoye in a public ceremony on February 14, 2016; the couple had held a private ceremony in January.[17][157] They have two children. The couple separated in November 2019, and their divorce was finalized in 2020.[24]

In March 2020, when Warnock and Ndoye were going through divorce proceedings, Ndoye accused Warnock of running over her foot with his car during a verbal argument; Warnock denied the accusation.[158] According to an Atlanta Police Department report, after Warnock called police to the scene, Ndoye was reluctant to show her foot to the responding police officer, who "did not see any signs that Ms. Ouleye's foot was ran [sic] over"; medical professionals then arrived at the scene, but were "not able to locate any swelling, redness, or bruising or broken bones" on Ndoye's foot.[159] Police did not charge Warnock with any crimes regarding the incident.[160]

In February 2022, Ndoye asked the court to modify their child custody agreement, granting her "additional custody of their two young children so she can complete a Harvard University program", and for a recalculation of child support payments.[161]

In October 2022, Savannah's city government honorarily renamed Cape Street, the street where Warnock grew up in public housing during the 1980s, Raphael Warnock Way.[162]

Electoral history

edit| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Raphael Warnock | 1,617,035 | 32.90 | |

| Republican | Kelly Loeffler (incumbent) | 1,273,214 | 25.91 | |

| Republican | Doug Collins | 980,454 | 19.95 | |

| Democratic | Deborah Jackson | 324,118 | 6.60 | |

| Democratic | Matt Lieberman | 136,021 | 2.77 | |

| Democratic | Tamara Johnson-Shealey | 106,767 | 2.17 | |

| Democratic | Jamesia James | 94,406 | 1.92 | |

| Republican | Derrick Grayson | 51,592 | 1.05 | |

| Democratic | Joy Felicia Slade | 44,945 | 0.91 | |

| Republican | Annette Davis Jackson | 44,335 | 0.90 | |

| Republican | Kandiss Taylor | 40,349 | 0.82 | |

| Republican | Wayne Johnson (withdrawn) | 36,176 | 0.74 | |

| Libertarian | Brian Slowinski | 35,431 | 0.72 | |

| Democratic | Richard Dien Winfield | 28,687 | 0.58 | |

| Democratic | Ed Tarver | 26,333 | 0.54 | |

| Independent | Allen Buckley | 17,954 | 0.37 | |

| Green | John Fortuin | 15,293 | 0.31 | |

| Independent | Al Bartell | 14,640 | 0.30 | |

| Independent | Valencia Stovall | 13,318 | 0.27 | |

| Independent | Michael Todd Greene | 13,293 | 0.27 | |

| Total votes | 4,914,361 | 100.0 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Raphael Warnock | 2,289,113 | 51.04% | +10.00% | |

| Republican | Kelly Loeffler (incumbent) | 2,195,841 | 48.96% | −5.84% | |

| Total votes | 4,484,954 | 100.0% | |||

| Democratic gain from Republican | |||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Raphael Warnock (incumbent) | 1,946,117 | 49.44% | +1.05% | |

| Republican | Herschel Walker | 1,908,442 | 48.49% | −0.88% | |

| Libertarian | Chase Oliver | 81,365 | 2.07% | +1.35% | |

| Total votes | 3,935,924 | 100.0% | |||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Raphael Warnock (incumbent) | 1,820,633 | 51.40% | +0.36% | |

| Republican | Herschel Walker | 1,721,244 | 48.60% | −0.36% | |

| Total votes | 3,541,877 | 100.0% | |||

| Democratic hold | |||||

Publications

edit| External videos | |

|---|---|

| After Words interview with Warnock on A Way Out of No Way, June 26, 2022, C-SPAN |

Books

edit- Warnock, Raphael G. (December 2013). The Divided Mind of the Black Church: Theology, Piety, and Public Witness. New York: NYU Press. ISBN 9780814794463. OCLC 844308880.

- Warnock, Raphael G. (June 2022). A Way Out of No Way. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 9780593491546.[167][168] OCLC 1281244406.

Articles

edit- "I Can Still Hear My Father's Voice", New York Times, June 15, 2022[169]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Sen. Raphael Warnock - D Georgia, In Office - Biography | LegiStorm". www.legistorm.com. Archived from the original on December 3, 2022. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- ^ Brack, Naomii (November 19, 2020). "Raphael G. Warnock (1969- )". BlackPast.org. Archived from the original on August 4, 2022. Retrieved August 3, 2022.

- ^ Bowman, Bridget (November 23, 2022). "Warnock launches direct-to-camera Thanksgiving ad". NBC News. Archived from the original on December 3, 2022. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- ^ a b Fausset, Richard (November 1, 2020). "Can Raphael Warnock Go From the Pulpit to the Senate?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020.

- ^ Rogers, Alex (January 30, 2020). "Rev. Raphael Warnock enters US Senate race in Georgia | CNN Politics". CNN. Archived from the original on February 20, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Williams, Ross (January 11, 2021). "Record turnout among Black voters helped Democrats claim Senate". Georgia Recorder. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- ^ a b Relman, John L. Dorman, Eliza. "Georgia voters will decide which party controls the Senate in 2 unusual runoff races in January". Business Insider. Archived from the original on November 27, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Martin, Jonathan; Fausset, Richard (January 6, 2021). "Warnock beats Loeffler in Georgia Senate race". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 7, 2021. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

The victory is a landmark breakthrough for African-Americans in politics. Mr. Warnock becomes the first Black Democrat to be elected to the Senate from the Deep South since reconstruction.

- ^ a b Beaumont, Peter (January 6, 2021). "Why Raphael Warnock was elected Georgia's first black US senator". the Guardian. Archived from the original on December 3, 2022. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ a b Waxman, Olivia (January 7, 2021). "'Another Milestone in the Long, Long Road.' Rev. Raphael Warnock's Georgia Senate Victory Made History in Multiple Ways". Time. Archived from the original on December 3, 2022. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ "Warnock, Raphael G." Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ Lewis, Ricardo (February 15, 2016). "From Public Housing to the People's Pastor: Savannah native uses pulpit as platform for change". WSAV-TV. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- ^ Jones, Tayari (June 23, 2022). "Senator Raphael Warnock Is Running Again for the Soul of Georgia". Time. Archived from the original on December 3, 2022. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ a b Jealous, Ben; Shorters, Trabian (February 3, 2015). Reach: 40 Black Men Speak on Living, Leading, and Succeeding. Simon and Schuster. pp. 227–. ISBN 978-1-4767-9983-4. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- ^ Bella, Timothy; Elfrink, Tim (January 6, 2021). "Warnock, Georgia's first Black senator, honors mother and 'the 82-year-old hands that used to pick somebody else's cotton'". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c Clark Felty, Dana (October 6, 2006). "From Kayton Homes to King's pulpit". Savannah Morning News. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- ^ a b Poole, Shelia (February 16, 2016). "Ebenezer's Pastor Raphael Warnock to wed in public ceremony on Sunday". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ a b "The Reverend Raphael Gamaliel Warnock, Ph. D." African American Heritage House. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- ^ McMahon, Julie (December 18, 2019). "Pastor at historic MLK Jr. church to speak at SU". The Post-Standard. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- ^ Woods, A. (January 30, 2020). "Who Is Raphael Warnock?: Everything To Know About Ebenezer Baptist Pastor Running For Georgia Senate". News One. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- ^ a b Raymond, Jonathan (July 30, 2020). "Rev. Raphael Warnock contrasts John Lewis with those who exhibit 'political cynicism and narcissism'". 11Alive.com. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ a b "Social activist, pastor of historic Ebenezer Baptist Church, to speak at Divinity School". YaleNews. February 21, 2013. Archived from the original on February 23, 2013. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ Beaumont, Peter (January 6, 2021). "Why Raphael Warnock was elected Georgia's first black US senator". the Guardian. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ a b Fausset, Richard (November 1, 2020). "Can Raphael Warnock Go From the Pulpit to the Senate?". New York Times. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ King, Maya (November 19, 2020). "Republicans paint Raphael Warnock as a religious radical". Politico. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ Greenhouse, Steven (August 4, 1997). "2 Well-Known Churches Say No to Workfare Jobs". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ a b Hollis, Henri (December 10, 2020). "Campaign check: Loeffler tries to link Warnock to Cuban dictator". ajc. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ^ "King's speech revered, but call to action missed". The Baltimore Sun. January 14, 2001. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ "Social activist, pastor of historic Ebenezer Baptist Church, to speak at Divinity School". YaleNews. February 21, 2013. Archived from the original on December 6, 2022. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ Phillips, Morgan (December 9, 2020). "Warnock allegedly 'extremely uncooperative' during 2002 child-abuse investigation, police records show". Fox News. Archived from the original on October 5, 2022. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ "2 ministers no longer facing charges of hindering probe". baltimoresun.com. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ Kertscher, Tom. "PolitiFact - No proof Warnock 'ran over' wife; obstruction case dropped". Politifact. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ Walker, Childs; Rivera, John (August 3, 2002). "City ministers accused of obstructing abuse probe". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- ^ "Ministers impeded probe, police allege". The News Journal. Wilmington, Delaware. Associated Press. August 4, 2002. p. B5. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Blake, John (October 1, 2005). "Lessons learned at dinner table". The Atlanta Constitution.

- ^ a b c Fausset, Richard (January 30, 2020). "Citing 'Soul of Our Democracy,' Pastor of Dr. King's Church Enters Senate Race". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- ^ McMahon, Julie (December 18, 2019). "Pastor at historic MLK Jr. church to speak at Syracuse University". Syracuse Post Standard. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ^ Rodriguez, Sabrina (December 1, 2022). "Obama returns to Georgia to rally support for Warnock in tight runoff race". New York Times. Archived from the original on December 3, 2022. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- ^ King, Maya (October 30, 2022). "The Senator-Pastor From Georgia Mixes Politics and Preaching on the Trail". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 5, 2022. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- ^ Dreyfuss, Joel (September 21, 2011). "Noted Reverend on Troy Davis: 'Moral Disaster'". Theroot.com. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- ^ Banks, Adelle M. (January 22, 2013). "Preachers pray for unity at National Cathedral inaugural service". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- ^ "The Rev. Raphael Warnock, Ebenezer Baptist Church to host interfaith meeting on climate with Al Gore, the Rev. William Barber II". The Atlanta Voice. March 13, 2019. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- ^ Fausset, Richard; Rojas, Rick (July 30, 2020). "John Lewis, a Man of 'Unbreakable Perseverance,' Is Laid to Rest". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 12, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2022.

- ^ Boorstein, Michelle (April 5, 2021). "Sen. Raphael Warnock's deleted Easter tweet reflects religious and political chasms about Christianity". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ Ellefson, Lindsay (April 5, 2021). "Sen Raphael Warnock Deletes Easter Tweet After Backlash From Religious Right". www.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on May 22, 2021. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ a b Bunn, Curtis (November 7, 2020). "'My ideals are driven by my faith': Raphael Warnock on his Senate runoff race". NBC News. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- ^ Warnock, Raphael (April 24, 2013). "Governor should follow students' example". Atlanta Journal Constitution.

- ^ a b "Atlanta's 55 Most Powerful: 51. Raphael Warnock". Atlantamagazine.com. October 1, 2015. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- ^ Buchsbaum, Herbert (March 18, 2014). "Budding Liberal Protest Movements Begin to Take Root in South". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 3, 2022. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ Davis, Janel (March 18, 2014). "Arrests follow protests at state Capitol". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- ^ Moser, Bob (July 29, 2014). "A bridge in Georgia". Facing South. The American Prospect. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved January 9, 2021.

- ^ Bluestein, Greg (August 6, 2015). "Exclusive: Pastor of historic Ebenezer Baptist Church considers U.S. Senate run". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ Bluestein, Greg (October 2, 2015). "Pastor of MLK's church will not run for Georgia Senate seat". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on July 6, 2017. Retrieved October 3, 2015.

- ^ Galloway, Jim; Bluestein, Greg; Mitchell, Tia (January 13, 2020). "The Jolt: Raphael Warnock prepares to run for Senate against Kelly Loeffler". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ "Board chair named at the New Georgia Project". Valdosta Today. Atlanta. June 8, 2017. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- ^ Fausset, Richard (November 1, 2020). "Can Raphael Warnock Go From the Pulpit to the Senate?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- ^ Miao, Hannah (December 23, 2020). "Democrats seize on Trump's push for $2,000 stimulus checks for boost in Georgia Senate race". CNBC. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved December 26, 2020.

- ^ Fausset, Richard (November 1, 2020). "Can Raphael Warnock Go From the Pulpit to the Senate?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2020.

- ^ Bluestein, Greg (May 20, 2020). "Georgia Senate: Abortion rights group backs Warnock's bid to unseat Loeffler". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2020.

- ^ Eloy, Michell (March 12, 2014). "Gun Control Advocates Decry Revamped House Gun Bill". WABE. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2020.

- ^ Suggs, Ernie (October 7, 2020). "Profile of Raphel Warnock, candidate for George U.S. Senate". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved December 15, 2020.

- ^ Bluestein, Greg (January 30, 2020). "Raphael Warnock, pastor of famed church, enters Georgia Senate race". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- ^ "Abrams' aide says Democrat had 'nearly impossible' chance to beat Kemp". ajc. Retrieved December 10, 2022.

- ^ Bluestein, Greg (September 29, 2020). "Jimmy Carter backs Warnock in crowded U.S. Senate race in Georgia". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- ^ Arkin, James (January 30, 2020). "Stacey Abrams, Dems rally around pastor in burgeoning Georgia Senate race". Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- ^ "Elizabeth Warren". Facebook. June 15, 2020. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

As a champion for fair wages, Reverend Raphael Warnock has stood up for working families for years. I'm proud to endorse him because I know with him in the Senate, Georgians will have a leader with the courage and conviction to put working families first.

- ^ Nadler, Ben (September 25, 2020). "Obama endorses Warnock in crowded Georgia Senate race". ABC News. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- ^ Deb, Sopan (August 5, 2020). "W.N.B.A. Players Escalate Protest of Anti-B.L.M. Team Owner". The New York Times. p. B9. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ Kapur, Sahil (January 5, 2021). "In Georgia, Democrats close with populist pitch vowing $2,000 stimulus checks". NBC News. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- ^ Stein, Jeff; Werner, Erica (January 6, 2021). "$2,000 stimulus checks could become a reality with Democratic control of the Senate". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 7, 2021.

- ^ Peoples, Steve; Barrow, Bill; Bynum, Russ (January 6, 2021). "Georgia election updates: Raphael Warnock makes history with win as Democrats near control of Senate; 2nd runoff race too early to call". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved January 9, 2021.

- ^ Ryan Nobles and Caroline Kenny. "Loeffler concedes Georgia Senate runoff to Warnock". CNN. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Gardner, Amy; Werner, Erica (January 19, 2021). "Georgia certifies Ossoff and Warnock victories, paving way for Democratic control of Senate". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on January 19, 2021. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- ^ Warnock, Reverend Raphael [@ReverendWarnock] (January 27, 2021). "Thanks to your support, we made history and flipped Georgia blue. But I'm already up for re-election, and Republicans are making plans right now to turn GA red again. Will you chip in $5 right now to jumpstart our re-election campaign?" (Tweet). Archived from the original on May 31, 2022. Retrieved February 12, 2021 – via Twitter.

- ^ Dorn, Sara (November 9, 2022). "Walker, Warnock Headed For A Runoff In Georgia Senate Race". Forbes. Archived from the original on November 11, 2022. Retrieved November 11, 2022.

- ^ "Raphael Warnock defeats Herschel Walker in Georgia Senate race". MSNBC. December 7, 2022.

- ^ "Raphael Warnock wins the Georgia Senate runoff | Fast facts about his victory". 11Alive.com. December 6, 2022. Retrieved December 7, 2022.

- ^ Weisman, Jonathan; King, Maya (December 6, 2022). "Warnock Beats Walker, Giving Democrats 51st Senate Seat". The New York Times.

- ^ "WATCH: Jon Ossoff, Raphael Warnock and Alex Padilla sworn into U.S. Senate, giving Democrats control". PBS NewsHour. January 20, 2021. Archived from the original on June 23, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2022.

- ^ Hayes, Christal. "Democrats officially take control of Senate after Harris swears in Ossoff, Warnock and Padilla". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on October 23, 2022. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ Harper, Averi; Thorbecke, Catherine (January 20, 2021). "Kamala Harris swears in 3 senators making their own history". ABC News. Archived from the original on November 9, 2022. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ "The Voter's Self Defense System". Vote Smart. Archived from the original on December 9, 2006. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ^ Booker, Brakkton (February 13, 2021). "Trump Impeachment Trial Verdict: How Senators Voted". NPR. Archived from the original on October 31, 2022. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ Sanders, Bernard (March 5, 2021). "S.Amdt.972 to S.Amdt.891 to H.R.1319 - 117th Congress (2021-2022) - Cosponsors". www.congress.gov. Archived from the original on June 14, 2021. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ Mitchell, Tia (March 17, 2021). "Warnock, in first floor speech, champions federal voting laws to blunt GA's proposed restrictions". AJC.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Nunez, Gabriella (January 6, 2022). "Sen. Rev. Warnock honors legacy of Johnny Isakson on the Senate floor". 11Alive. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ "Senate passes unanimous resolution honoring late Sen. Johnny Isakson". Fox 5 Atlanta. January 5, 2022. Archived from the original on November 12, 2022. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ Nunez, Gabriella (October 4, 2022). "Atlanta's John R. Lewis Post Office is now established in his former congressional district". 11Alive. Retrieved November 30, 2022.

- ^ Figueroa, Ariana (February 2, 2022). "U.S. House votes to name Atlanta post office for the late Rep. John Lewis". Georgia Recorder. Archived from the original on December 5, 2022. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ Glorno, Taylor (September 27, 2023). "Cannabis banking bill clears Senate committee". The Hill. Retrieved October 15, 2023.

- ^ Mitchell, Tia. "Ossoff, Warnock receive their Senate committee assignments". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- ^ "Congressional Black Caucus". cbc.house.gov. Archived from the original on December 5, 2022. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ Mitchell, Tia. "Georgia lawmakers welcome return of Black Caucus conference, festivities". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. ISSN 1539-7459. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ a b Everett, Burgess; Arkin, James (April 27, 2021). "Democrats' surprising 2-man team to hold the Senate". POLITICO. Archived from the original on March 24, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ^ Bycoffe, Aaron; Silver, Nate. "Does Your Member Of Congress Vote With Or Against Biden? – Raphael Warnock". FiveThirtyEight. ABC News. Archived from the original on February 11, 2022. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- ^ "Sen. Raphael Warnock's 2022 Report Card". GovTrack. February 12, 2023. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ Ziegler, Mary (December 31, 2020). "How Raphael Warnock Came to Be an Abortion-Rights Outlier". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on February 11, 2022. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ King, Maya (May 11, 2022). "How abortion is already animating the Senate race in Georgia". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 5, 2022. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ Peebles, Will. "Group of Black pastors criticizes Senate candidate Raphael Warnock for his abortion stance". Savannah Morning News. Archived from the original on May 14, 2021. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ Warnock, Raphael (June 24, 2022). ""The Supreme Court's misguided decision to overturn Roe v. Wade is devastating for women and families in Georgia and nationwide."". Twitter. Archived from the original on October 5, 2022. Retrieved June 24, 2022.

- ^ Bluestein, Greg (June 24, 2022). "Abortion ruling likely shifts focus of Georgia 2022 campaigns". ajc. Archived from the original on December 5, 2022. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ "Georgia lawmakers, leaders react to overturning of Roe v. Wade". 11Alive.com. June 24, 2022. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ "Emergency Relief for Farmers of Color Act of 2021 (S. 278)". GovTrack.us. Archived from the original on October 25, 2022. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ Wiley, Kenny (June 19, 2021). "USDA, Prairie View A&M leaders discuss debt relief plan for farmers of color". The Bryan-College Station Eagle. Archived from the original on April 17, 2022. Retrieved October 4, 2022.

- ^ Kenmore, Abraham (October 14, 2022). "Abortion? Inflation? What will Herschel Walker-Raphael Warnock U.S. Senate debate cover?". Savannah Morning News. Archived from the original on December 6, 2022. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ Kruse, Michael (August 5, 2022). "'There's Never Been Anybody Like Him in the United States Senate'". Politico Magazine. Archived from the original on November 28, 2022. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ Warren, Michael (October 14, 2022). "In battleground Georgia, the Kemp-Warnock voter is the target for both parties in 2022 and beyond". CNN. Archived from the original on October 27, 2022. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ a b Scott, Eugene (January 6, 2021). "Analysis | What you need to know about Raphael Warnock". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ Mitchell, Tia (June 20, 2022). "U.S. House subcommittee rejects Biden plan to close Savannah military facility". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on November 12, 2022. Retrieved November 30, 2022.

- ^ Coy, Greg (December 1, 2021). "Georgia senator says NDAA will benefit military bases in Savannah". WJCL (TV). Archived from the original on January 26, 2022.

- ^ "New housing facility coming to Fort Stewart". WTOC-TV. September 29, 2021. Archived from the original on November 30, 2022. Retrieved November 30, 2022.

- ^ Volk, Will (August 21, 2021). "Warnock visits Augusta, discusses plans for I-14 to stretch from Texas to CSRA". WRDW-TV. Archived from the original on August 22, 2021.

- ^ "Congress designates Interstate 14 across five states with I-14 corridor through San Angelo". San Angelo Standard-Times. November 15, 2021. Archived from the original on November 12, 2022. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ Bunch, Riley (October 21, 2022). "U.S. Senate race voter guide: Warnock, Walker on the issues". Georgia Public Broadcasting. Archived from the original on December 2, 2022. Retrieved November 30, 2022.

- ^ "Inland rail port for NE Georgia getting $2M federal grant". AP NEWS. June 13, 2021. Archived from the original on October 22, 2022. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ Ford, Hope (March 6, 2021) [March 5, 2021]. "Senator Warnock on stimulus package, federal minimum wage, and voting rights bills". 11 Alive, WXIA-TV.

- ^ Iacurci, Greg (January 6, 2021). "$15 minimum wage edges closer as Democrats win Senate control". CNBC. Archived from the original on May 18, 2022.

- ^ a b Lutz, Meris. "Climate change remains partisan issue in Georgia elections". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. ISSN 1539-7459. Archived from the original on November 9, 2022. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- ^ a b Waldman, Scott. "Young Climate Voters Could Tilt Georgia's Runoff Election for Senate". Scientific American. Archived from the original on November 29, 2022. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- ^ "Senator Raphael G. Warnock (1969 - )".

- ^ "S.3742 - Recycling Infrastructure and Accessibility Act of 2022".

- ^ "NRAPVF | Grades | Georgia". nrapvf.org. NRA-PVF. Archived from the original on January 5, 2021. Retrieved August 30, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Defend Freedom. Defeat Raphael Warnock". NRA-PVF. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ Richardson, Valerie (December 1, 2020). "NRA ad rips Georgia Democrat Warnock for joking about concealed-carry in church". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on March 29, 2021. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ a b Helm, Clare (October 5, 2021). "Macon community health centers get $1.3M in American Rescue Plan funds". WGXA. Archived from the original on November 30, 2022. Retrieved November 30, 2022.

- ^ "Albany community health centers get $2.8M in American Rescue Plan funds". WXFL. October 5, 2021. Archived from the original on November 30, 2022. Retrieved November 30, 2022.

- ^ a b c Ford, Hope (March 10, 2022). "Georgia has one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the nation. Here's how the government spending plan can help". 11Alive. Retrieved November 30, 2022.

- ^ a b Bunch, Riley (August 8, 2022). "Georgia Democrats score legislative wins in Senate spending bill". Georgia Public Broadcasting. Archived from the original on November 30, 2022. Retrieved November 30, 2022.

- ^ "CNN.com - Transcripts". transcripts.cnn.com. Archived from the original on June 14, 2021. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ Mitchell, Tia; Murphy, Patricia; Bluestein, Greg. "The Jolt: Immigrant groups unhappy with Warnock criticism of new border policy". Political Insider (The Atlanta Journal-Constitution). Archived from the original on May 15, 2022. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ "HRC Endorses Warnock for U.S. Senate, Bush and Williams for U.S. House". September 22, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2023.

- ^ Luneau, Delphine (November 9, 2022). "Human Rights Campaign Congratulates Senator Raphael Warnock, Pledges Continued Support as He Heads to December Runoff Election". Retrieved October 15, 2023.

- ^ Bauer, Sydney (January 9, 2021). "LGBTQ Georgians hopeful following Warnock, Ossoff Senate victories". NBC News. Archived from the original on February 11, 2022. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ^ Mitchell, Tia. "Warnock breaks from campaigning to cast vote on gay marriage protection". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. ISSN 1539-7459. Archived from the original on November 24, 2022. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- ^ Kapur, Sahil (November 29, 2022). "Senate passes bill to protect same-sex and interracial marriage over GOP opposition". NBC News. Retrieved April 9, 2023.

- ^ Hollis, Henri (December 16, 2020). "Campaign check: Loeffler says Warnock will 'pack' Supreme Court". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on February 11, 2022. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ Cieslak, McKenna (August 31, 2021). "Sens. Ossoff & Warnock announce over $2.5 million to help homeless Georgia veterans reenter the workforce". WSAV-TV. Archived from the original on November 30, 2022. Retrieved November 30, 2022.

- ^ "Sens. Ossoff, Warnock announce resources to help veterans reenter the workforce". WFXL. July 6, 2022. Archived from the original on November 30, 2022. Retrieved November 30, 2022.

- ^ McCullough, Kim (September 23, 2021). "Warnock, Hyde-Smith pass bipartisan resolution honoring Gold Star families". WRDW-TV. Archived from the original on November 12, 2022. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ Kheel, Rebecca (November 30, 2021). "Racial Disparities in VA Benefits Advocates Say Are Rampant Set to Get Watchdog Probe". Military.com. Archived from the original on November 30, 2022. Retrieved November 30, 2022.

- ^ Mitchell, Tia. "Warnock, in first floor speech, champions federal voting laws to blunt GA's proposed restrictions". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. ISSN 1539-7459. Archived from the original on October 5, 2022. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

- ^ Kelly, Mary Louise (March 11, 2021). "Sen. Raphael Warnock On Ending The Filibuster: 'All Options Must Be On The Table'". NPR.org. Archived from the original on February 11, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ^ Garcia, Catherine (March 18, 2021). "Georgia Sen. Warnock warns voting rights are under assault at a rate not seen 'since the Jim Crow era'". The Week. Archived from the original on March 18, 2021. Retrieved March 19, 2021.

- ^ Barrow, Bill (March 17, 2021). "Warnock: GOP voting restrictions resurrect 'Jim Crow era'". Associated Press. Archived from the original on March 29, 2021. Retrieved March 19, 2021.

- ^ "Warnock addresses Senate committee on voting rights". wrdw.com. April 20, 2021. Archived from the original on February 11, 2022. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ Blake, Aaron (June 21, 2021). "Stacey Abrams and the Democrats' evolution on voter ID". Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 15, 2022. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ^ Brittany Bernstein (June 17, 2021). "Stacey Abrams Endorses Manchin's Election Law Compromise". National Review. Archived from the original on February 11, 2022. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ^ Greenhouse, Steven (August 4, 1997). "2 Well-Known Churches Say No to Workfare Jobs". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ^ a b "Warnock clarifies stances on Israel, Palestinians after 2018 speech surfaces". Jewish News Syndicate.

- ^ "Raphael Warnock's Israel stance is suddenly an issue in his Georgia Senate campaign". The Forward. November 11, 2020. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "Senator Reverend Warnock Statement on Hamas Attack on Israel » Reverend Raphael Warnock". Reverend Raphael Warnock. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "WATCH: Laying out His Moral Vision for a Peaceful Future, Senator Reverend Warnock Delivers Senate Floor Speech Calling for Negotiated Ceasefire in the Israel-Hamas War » Reverend Raphael Warnock". Reverend Raphael Warnock. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Bolton, Alexander (March 20, 2024). "Senate Democrats press Biden to establish two-state solution for Israel, Palestine". The Hill. Retrieved October 30, 2024.

- ^ "Full List of Democrats Who Voted to Block Weapons to Israel". Newsweek. November 21, 2024. Archived from the original on November 22, 2024. Retrieved December 7, 2024.

- ^ "US Senate to consider measures blocking some arms sales to Israel". Reuters. November 18, 2024. Archived from the original on November 21, 2024. Retrieved December 7, 2024.

- ^ "Editorial: Warnock's Senate bid big for Savannah". Savannah Morning News. January 30, 2020. Archived from the original on December 1, 2021. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

- ^ Poole, Shelia (February 16, 2016). "A look at the wedding of Rev. Raphael Warnock and Ouleye Ndoye". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

The Rev. Raphael G. Warnock, senior pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church, and Ouleye Ndoye were wed publicly on Valentine's Day at the Auburn Avenue church. They initially wed in a private ceremony last month in Danforth Chapel on the campus of Morehouse College, Warnock's alma mater.

- ^ Deese, Kaelan (December 24, 2020). "Warnock says he'll focus on Georgians after video of ex-wife surfaces". The Hill. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved December 26, 2020.

- ^ Kertscher, Tom (November 16, 2020). "No proof Warnock 'ran over' wife; obstruction case dropped". PolitiFact. Archived from the original on November 15, 2022. Retrieved November 10, 2022.

- ^ Deere, Stephen; Bluestein, Greg (March 7, 2020). "Warnock, wife involved in dispute". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- ^ Bluestein, Greg (April 2, 2022). "Warnock's ex-wife takes legal action over child custody". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on April 9, 2022. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ Payne, Benjamin (October 7, 2022). "Raphael Warnock's childhood street in Savannah bears new name in his honor". Georgia Public Broadcasting. Archived from the original on November 24, 2022. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- ^ "2020 General Election Official Results - US SENATE (LOEFFLER) - SPECIAL". Georgia Secretary of State. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ "Georgia U.S. Senate runoff results". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved January 9, 2021.

- ^ "United States Senate - November 8, 2022 General Election". Georgia Secretary of State. November 12, 2022. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ "December 6, 2022 - General Election Runoff Unofficial Results". Georgia Secretary of State. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ Kaiser, Charles (June 18, 2022). "A Way Out of No Way review: Raphael Warnock, symbol of hope for America". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 18, 2022. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ Joyner, Tammy (June 17, 2022). "Sen. Warnock recounts his path from the projects to Georgia politics". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ Warnock, Raphael (June 15, 2022). "Opinion | Raphael Warnock: I Can Still Hear My Father's Voice". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

External links

edit- Senator Raphael Warnock official U.S. Senate website

- Warnock for Georgia Archived March 4, 2021, at the Wayback Machine campaign website

- Biography at the Ebenezer Baptist Church

- Appearances on C-SPAN