The Estonian Reform Party (Estonian: Eesti Reformierakond) is a liberal political party in Estonia.[2][3] The party has been led by Kristen Michal since 2024. It is colloquially known as the "Squirrel Party" (Estonian: Oravapartei), referencing its logo.[4][5]

Estonian Reform Party Eesti Reformierakond | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chairperson | Kristen Michal |

| General Secretary | Timo Suslov |

| Founder | Siim Kallas |

| Founded | 18 November 1994 |

| Merger of |

|

| Headquarters | Tallinn, Tõnismägi 9 10119 |

| Newspaper | Paremad Uudised Reformikiri |

| Youth wing | Estonian Reform Party Youth |

| Membership (2024) | |

| Ideology | Liberalism (Estonian) |

| Political position | |

| European affiliation | Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Party |

| European Parliament group | Renew Europe |

| International affiliation | Liberal International |

| Colours |

|

| Slogan | Parem Eesti kõigile ('A Better Estonia for Everyone') |

| Riigikogu | 38 / 101 |

| Municipalities | 244 / 1,717 |

| European Parliament | 1 / 7 |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Website | |

| reform | |

It was founded in 1994 by Siim Kallas, then-president of the Bank of Estonia, as a split from Pro Patria National Coalition Party. As the Reform Party has participated in most of the government coalitions in Estonia since the mid-1990s, its influence has been significant, especially regarding Estonia's free market and policies of low taxation. The party has been a full member of Liberal International since 1996, having been an observer member between 1994 and 1996, and a full member of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE). Reform Party leaders Siim Kallas, Taavi Rõivas, Andrus Ansip and Kaja Kallas have all served as prime ministers of Estonia. From 17 April 2023, the party has been the senior member in a coalition government with the Social Democratic Party and Estonia 200.

History

editThe Estonian Reform Party was founded on 18 November 1994,[6] joining together the Reform Party – a splinter from the Pro Patria National Coalition (RKEI) – and the Estonian Liberal Democratic Party (ELDP). The new party, which had 710 members at its foundation,[6] was led by Siim Kallas, who had been president of the Bank of Estonia. Kallas was not viewed as being associated with Mart Laar's government and was generally considered a proficient central bank governor, having overseen the successful introduction of the Estonian kroon.[7] The party formed ties with the Free Democratic Party of Germany, the Liberal People's Party of Sweden, the Swedish People's Party of Finland, and Latvian Way.[6]

Siim Kallas

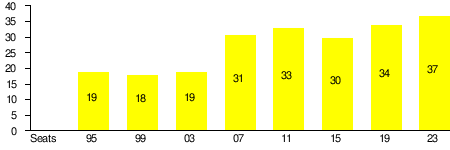

editSiim Kallas was leader of the Reform Party from 1994 to 2004. He was Prime Minister of Estonia from 2002 to 2003. In the party's first parliamentary election in March 1995, it won 19 seats, catapulting it into second place, behind the Coalition Party. Tiit Vähi tried to negotiate a coalition with the Reform Party, but the talks broke down over economic policy,[8] with the Reform Party opposing agricultural subsidies and supporting the maintenance of Estonia's flat-rate income tax.[7] While the Coalition Party formed a new government with the Centre Party at first, a taping scandal involving Centre Party leader Edgar Savisaar led to the Reform Party replacing the Centre Party in the coalition in November 1995.[9] Kallas was appointed as Minister of Foreign Affairs, with five other Reform Party members serving in the cabinet. The Reform Party left the government in November 1996 after the Coalition Party signed a cooperation agreement with the Centre Party without consulting them.[9]

At the 1999 election, the Reform Party dropped one seat to 18, finishing third behind the Centre Party and the conservative Pro Patria Union.[10] The ER formed a centre-right coalition with the Pro Patria Union and the Moderates, with Mart Laar as Prime Minister and Siim Kallas as Minister of Finance, and with Toomas Savi returned as Speaker.[10] Although the coalition was focused on EU and NATO accession, the Reform Party successfully delivered its manifesto pledge to abolish the corporate tax,[10] one of its most notable achievements.[11] After the October 1999 municipal elections, the three parties replicated their alliance in Tallinn.[12]

The party served in government again from March 1999 to December 2001 in a tripartite government with Pro Patria Union and People's Party Moderates, from January 2002 to March 2003 with the Estonian Centre Party, from March 2003 to March 2005 with Res Publica and People's Union, from March 2005 to March 2007 with the Centre Party and People's Union, from March 2007 to May 2009 with the Pro Patria and Res Publica Union and the Social Democratic Party. From May 2009 the Reform Party was in a coalition government with the Pro Patria and Res Publica Union.

Andrus Ansip

editAndrus Ansip was Prime Minister of Estonia from April 2005 to March 2014. After the 2007 parliamentary election the party held 31 out of 101 seats in the Riigikogu, receiving 153,040 votes (28% of the total), an increase of +10%, resulting in a net gain of 12 seats.

Taavi Rõivas

editFollowing the resignation of Andrus Ansip, a new cabinet was installed on 24 March 2014, with Taavi Rõivas of the Reform Party serving as Prime Minister in coalition with the Social Democratic Party (SDE).[13]

In the 2014 European elections held on 25 May 2014, the Reform Party won 24.3% of the national vote, returning two MEPs.[14]

In the 2015 parliamentary election held on 1 March 2015, the Reform Party received 27.7% of the vote and 30 seats in the Riigikogu.[15] It went on to form a coalition with Social Democratic Party and Pro Patria and Res Publica Union. In November 2016, the coalition split because of internal struggle.[16] After coalition talks, a new coalition was formed between Center Party, SDE and IRL, while Reform Party was left in the opposition for the first time since 1999.[17] Rõivas subsequently stepped down as the chairman of the party.[18]

Hanno Pevkur

editOn 7 January 2017, Hanno Pevkur was elected the new chairman of the Reform Party.[19] Pevkur's leadership was divided from the start and he faced increasing criticism till the end of the year. On 13 December 2017, Pevkur announced that he would not run for the chairmanship from January 2018.[20]

Kaja Kallas

editKaja Kallas was elected party leader on 14 April 2018.[21]

Under Kallas' leadership during the 2019 election, the Reform Party achieved its best electoral result to date with 28.8% of the vote and 34 seats, although it initially did not form a government and remained in opposition to the second Ratas government.

In January 2021, after the resignation of Jüri Ratas as Prime Minister, Kallas formed a Reform Party-led coalition government with the Estonian Centre Party.[22] However, on 3 June 2022, Kallas dismissed the seven ministers affiliated with the Centre Party,[23] governing as a minority government until a new coalition government with Isamaa and SDE as minority partners was formed on 8 July.[24]

In the 2023 parliamentary election, the Reform Party improved on its 2019 electoral performance, with 31.2% of the vote 37 seats. On 7 March 2023, the party initiated coalition negotiations with the new Estonia 200 party and the SDE.[25] A coalition agreement between the three parties was reached by 7 April,[26] allocating seven ministerial seats for the Reform Party,[27] and was officially signed on 10 April.[28] On 17 April, the third Kallas government was sworn into office.[29]

In July 2024, Kristen Michal became Estonia’s new prime minister to succeed Kaja Kallas, who resigned as prime minister on July 15 to become the European Union’s new High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy.[30]

Ideology and platform

editThis section needs to be updated. (March 2023) |

Described as being on the centre,[31][32] centre-right,[33] or right-wing[34] of the political spectrum, the Estonian Reform Party has variously been described in its ideological orientation as liberal,[2][3][35] classical-liberal,[36][37] liberal-conservative,[38][39] and conservative-liberal.[40][41] The party has consistently advocated policies of economic liberalism[11][42] and fiscal conservatism,[43] and has also been described as neoliberal.[34][44]

- The party supports Estonian 0% corporate tax on re-invested income and wants to eliminate the dividend tax.

- The party wanted to cut flat income tax rate from 22% (in 2007) to 18% by 2011. Because of the economic crisis, the campaign for cutting income tax rate was put on hold with the tax rate at 21% in 2008 and 2009.

- The party used to oppose VAT general rate increases until late spring 2009, when it changed its position in the light of the dire economic crisis and the need to find more money for the budget. VAT was increased from 18% to 20% on 1 July 2009.[45]

Political support

editThis section needs to be updated. (September 2021) |

The party is supported predominantly by young, well-educated, urban professionals. The Reform Party's vote base is heavily focused in the cities; although it receives only one-fifth of its support from Tallinn, it receives three times as many votes from other cities, despite them being home to fewer than 40% more voters overall.[46]

Its voter profile is significantly younger than average,[47] while its voters are well-educated, with the fewest high school drop-outs of any party.[46] Its membership is the most male-dominated of all the parties,[48] yet it receives the support of more female voters than average.[47] Reform Party voters also tend to have higher incomes, with 43% of Reform Party voters coming from the top 30% of all voters by income.[46]

Organisation

editThis article needs to be updated. (December 2016) |

The Reform Party has been a full member of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Party (formerly the European Liberal Democrat and Reform Party, ELDR) since December 1998.[49] In the European Parliament, the party's MEPS Andrus Ansip and Urmas Paetsits in the ALDE group in the Assembly. The Reform Party has been a full member of the Liberal International since 1996, having been an observer member from 1994 to 1996.

The party claims to have 12,000 members.[50]

The party's youth wing is the Estonian Reform Party Youth, which includes members aged 15 to 35. The organisation claims to have 4,500 members, and its chairman is Doris Lisett Rudnevs.[51]

Election results

editParliamentary elections

edit| Election | Leader | Votes | % | Seats | +/– | Government |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | Siim Kallas | 87,531 | 16.19 (#2) | 19 / 101

|

New | Opposition (1995) |

| Coalition (1995–1996) | ||||||

| Opposition (1996–1999) | ||||||

| 1999 | 77,088 | 15.92 (#3) | 18 / 101

|

1 | Coalition | |

| 2003 | 87,551 | 17.69 (#3) | 19 / 101

|

1 | Coalition | |

| 2007 | Andrus Ansip | 153,044 | 27.82 (#1) | 31 / 101

|

12 | Coalition |

| 2011 | 164,255 | 28.56 (#1) | 33 / 101

|

2 | Coalition | |

| 2015 | Taavi Rõivas | 158,970 | 27.69 (#1) | 30 / 101

|

3 | Coalition (2015–2016) |

| Opposition (2016–2019) | ||||||

| 2019 | Kaja Kallas | 162,363 | 28.93 (#1) | 34 / 101

|

4 | Opposition (2019–2021) |

| Coalition (2021–2023) | ||||||

| 2023 | 190,632 | 31.24 (#1) | 37 / 101

|

3 | Coalition |

European Parliament elections

edit| Election | List leader | Votes | % | Seats | +/– | EP Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | Toomas Savi | 28,377 | 12.22 (#3) | 1 / 6

|

New | ALDE |

| 2009 | Kristiina Ojuland | 79,849 | 15.32 (#3) | 1 / 6

|

0 | |

| 2014 | Andrus Ansip | 79,849 | 24.31 (#1) | 2 / 6

|

1 | |

| 2019 | 87,158 | 26.2 (#1) | 2 / 7

|

0 | RE | |

| 2024 | Urmas Paet | 66,017 | 17.93 (#3) | 1 / 7

|

1 |

European representation

editIn the European Parliament, the Estonian Reform Party sits in the Renew Europe group with two MEPs.[52][53]

In the European Committee of the Regions, the Estonian Reform Party sits in the Renew Europe CoR group, with two full and one alternate members for the 2020–2025 mandate.[54][55]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Äriregistri teabesüsteem" (in Estonian). Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ a b Mindaugas Kuklys (2014). "Recruitment of parliamentary representatives in an ethno-liberal democracy". In Elena Semenova; Michael Edinger; Heinrich Best (eds.). Parliamentary Elites in Central and Eastern Europe: Recruitment and Representation. Routledge. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-317-93533-9.

- ^ a b Elisabeth Bakke (2010). "Central and Southeast European Politics since 1989". In Sabrina P. Ramet (ed.). Central and East European party systems since 1989. Cambridge University Press. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-1-139-48750-4.

- ^ Oskolkov, Petr (January 2020). "Estonia's party system today: electoral turbulence and changes in ethno-regional patterns". Baltic Region. 12. Moscow: 6. doi:10.5922/2079-8555-2020-1-1. S2CID 216522189.

- ^ "Estonia: Kaja Kallas and the liberal Estonia of the future". www.freiheit.org. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ a b c Bugajski (2002), p. 64

- ^ a b Nørgaard (1999), p. 75

- ^ Dawisha, Karen; Parrott, Bruce (1999). The Consolidation of Democracy in East-Central Europe. London: Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 352. ISBN 978-1-85898-837-5.

- ^ a b Europa Publications (1998), p 336

- ^ a b c Bugajski (2002), p. 52

- ^ a b Berglund et al (2004), p 67

- ^ Bugajski (2002), p. 53

- ^ "Estonia swears in EU's youngest PM, Taavi Roivas". Vanguard News. 26 March 2014. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ "Euroopa Parlamendi valimised". ep2014.vvk.ee.

- ^ "Riigikogu valimised". rk2015.vvk.ee.

- ^ "Prime Minister loses no confidence vote, forced to resign". ERR. 9 November 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- ^ "49th cabinet of Estonia sworn in under Prime Minister Jüri Ratas". ERR. 23 November 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ "Reform Party chairmanship debate behind closed doors, internal voting to end on Thursday". ERR. 5 January 2017. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- ^ "Hanno Pevkur elected new Reform Party chairman". ERR. 8 January 2017. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- ^ "Pevkur not to run for Reform lead again, Kallas not announcing yet". ERR. 13 December 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ "Estonia's struggling Reform Party picks first female leader". The Sydney Morning Herald. 15 April 2018. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ^ "Kaja Kallas to become Estonia's first female prime minister". euronews. 24 January 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ "Estonian prime minister dismisses junior coalition partner from government". 3 June 2022.

- ^ "Reform, SDE, Isamaa strike coalition agreement". 8 July 2022.

- ^ "Estonia's Reform Party starts coalition government talks". The Independent. 8 March 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ "SDE leader: Coalition agreement ready, includes tax changes". 7 April 2023.

- ^ "Coalition agreement: VAT, income tax to rise by 2 percentage points". 8 April 2023.

- ^ "Gallery: Reform, Eesti 200 and SDE sign coalition agreement". Err. 10 April 2023.

- ^ "Riigikogu gives Kaja Kallas mandate to form new government". Err. 12 April 2023.

- ^ "Estonia's parliament backs Kristen Michal as new PM". POLITICO. 22 July 2024.

- ^ Garlick, Stuart; Sibierski, Mary (1 March 2015). "Estonia's pro-NATO Reform party wins vote overshadowed by Russia". AFP via Yahoo! News. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

"The Reform Party is the 2015 winner of the parliamentary elections," Roivas announced on Estonia's ERR public television late Sunday as official results showed his centrist Reform party won despite losing three seats.

- ^ Walker, Shaun. "Racism, sexism, Nazi economics: Estonia's far right in power". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- ^

- Marju Lauristin; Sten Hansson (2019). "Estonia". In Miloš Gregor; Otto Eibl (eds.). Thirty Years of Political Campaigning in Central and Eastern Europe. Springer International. p. 27. ISBN 978-3-03-027693-5.Vello Pettai (2019). "Estonia: From Instability to the Consolidation of Centre-Right Coalition Politics". In Torbjörn Bergman; Gabriella Ilonszki; Wolfgang C. Müller (eds.). Coalition Governance in Central Eastern Europe. Oxford University Press. pp. 170–185. ISBN 978-0-19-884437-2.

- Kjetil Duvold; Sten Berglund; Joakim Ekman (2020). Political Culture in the Baltic States: Between National and European Integration. Springer Nature. p. 72. ISBN 978-3-030-21844-7.

- Osborne, Samuel (4 March 2019). "Estonia election: Far right surges as centre-right Reform party pulls off surprise win". The Independent. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- "Estonia general election: Opposition party beats Centre rivals". BBC News. 3 March 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- "Pro-EU opposition wins Estonian elections, far right makes big gains". EURACTIV.com with Reuters. 4 March 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- ^ a b Dorothea Keudel-Kaiser (2014). Government Formation in Central and Eastern Europe: The Case of Minority Governments. Verlag Barbara Budrich. p. 115. ISBN 9783863882372.

- ^ J. Denis Derbyshire; Ian Derbyshire, eds. (2016). Encyclopedia of World Political Systems, Volume One. Routledge. p. 377. ISBN 978-1-317-47156-1.

- ^ Caroline Close; Pascal Delwit (2019). "Liberal parties and elections: Electoral performances and voters' profile". In Emilie van Haute; Caroline Close (eds.). Liberal Parties in Europe. Taylor & Francis. p. 295. ISBN 978-1-351-24549-4.

- ^ Smith, Alison F. (2020). Political party membership in new democracies electoral rules in Central and East Europe. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3-030-41796-3. OCLC 1154544689.

- ^ Alari Purju (2003). "Economic Performance and Market Reforms". In Marat Terterov; Jonathan Reuvid (eds.). Doing Business with Estonia. GMB Publishing Ltd. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-905050-56-7.

- ^ Kjetil Duvold (2017). "When Left and Right is a Matter of Identity: Overlapping Political Dimensions in Estonia and Latvia". In Andrey Makarychev; Alexandra Yatsyk (eds.). Borders in the Baltic Sea Region: Suturing the Ruptures. Springer. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-352-00014-6.

- ^ Hans Slomp (2011). Europe, a Political Profile: An American Companion to European Politics. ABC-CLIO. p. 525. ISBN 978-0-313-39181-1.

- ^ "Die estnischen Parteien". Der Standard. 5 March 2007. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ "Estonia's opposition Reform Party wins general election | DW | 3 March 2019". Deutsche Welle. 3 March 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ "Estonian Politicians Maneuvers to Form Coalition Government". Voice of America. 3 March 2003. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ Piret Ehin; Tonis Saarts; Mari-Liis Jakobson (2020). "Estonia". In Vít Hloušek; Petr Kaniok (eds.). The European Parliament Election of 2019 in East-Central Europe: Second-Order Euroscepticism. Springer Nature. p. 89. ISBN 978-3-030-40858-9.

- ^ "Eesti Rahvus Ringhääling". 21 August 2014.

- ^ a b c Berglund et al (2004), p 65

- ^ a b Kulik and Pshizova (2005), p. 153

- ^ Kulik and Pshizova (2005), p. 151

- ^ "History : ELDR 1976 – 2009". European Liberal Democrat and Reform Party. Archived from the original on 2 March 2009. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ "Organisatsioon" (in Estonian). Estonian Reform Party. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ "Juhtimine" (in Estonian). Estonian Reform Party Youth. 11 April 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ "Home | Andrus ANSIP | MEPs | European Parliament". www.europarl.europa.eu. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ "Home | Urmas PAET | MEPs | European Parliament". www.europarl.europa.eu. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ "Members Page CoR".

- ^ "Members Page CoR".

Cited sources

edit- Bugajski, Janusz (2002). Political Parties of Eastern Europe: A Guide to Politics in the Post-Communist Era. London: M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-1-56324-676-0.

- Europa Publications (1998). Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-85743-058-5.

- Nørgaard, Ole (1999). The Baltic States After Independence. London: Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85898-837-5.

- Berglund, Sten; Ekman, Joakim; Aarebrot, Frank H. (2004). The Handbook of Political Change in Eastern Europe. London: Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84064-854-6.

- Kulik, Anatoly; Pshizova, Susanna (2005). Political Parties in Post-Soviet Space: Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, and the Baltics. New York: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-97344-5.

External links

edit- Official website (in Estonian)

- Estonian Reform Party faction description of the party on the Riigikogu website