This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2008) |

The Rainier Valley (/reɪˈnɪər/ ray-NEER) is a neighborhood in southeastern Seattle, Washington. It is located east of Beacon Hill; west of Mount Baker, Seward Park, and Leschi; south of the Central District and north of Rainier Beach. It is part of Seattle's South End.

Rainier Valley | |

|---|---|

Aerial view of Rainier Valley, with downtown Seattle in the background, taken in 2001 | |

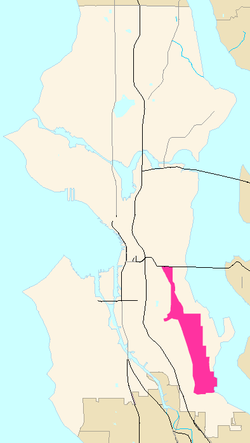

Map of Seattle with the general boundaries of Rainier Valley highlighted | |

| Coordinates: 47°32′10″N 122°16′30″W / 47.536°N 122.275°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Washington |

| County | King County |

| City | Seattle |

| Area code | 206 |

History

editWhite explorers and settlers first arrived in the area in the 1850s, and an explorer named Issac Ebey surveyed the area in 1850, with Ebey's assessment printed in an Oregon newspaper to entice other settlers. Native Americans had several encampments in the area prior to the settlers, and a permanent village at the south end of the valley.[1]

Italians were prominent in the north Valley in the early 20th century, the Central Valley was mostly settled by the same settlers and northern-European immigrants (primarily British and Scandinavian) who settled most of Seattle. Japanese farmers lived in the Valley since its inception and established two historic Japanese-American nurseries in the Valley - Mizukis and Holly Park, with Holly Park Nursery. Two housing projects were completed in the Valley during World War II named; Holly Park and Rainier Vista. The housing projects were completed by the Seattle Housing Authority to house Boeing and shipyard workers during the war.[2] Following the war through the Boeing crash of 1971, the Valley boomed with middle-class residential construction and with all of this construction, the Valley continued its historic diversity. [citation needed] Interracial couples in the 1950s found the Valley more accepting than the northern half of the city because of the relative lack of "deed covenants" found in the South End (covenants ruled unconstitutional by the United States Supreme Court in the 1960s).

The Civil Rights Act precipitated a "white flight" from the valley despite its historic diversity. The general exodus of whites from the valley, Beacon Hill, and Seward Park, which began in the mid-60s, was primarily over by the mid-80s, when some historic "children of the Valley" began to return to it, as well as other new residents. With the end of the Vietnam War in 1975, a wave of Vietnamese immigrants opened businesses along abandoned areas of Martin Luther King Jr. Way South, extending four miles south of the official Little Saigon neighborhood on South Jackson Street. Additional population growth was seen with the arrival of Filipinos throughout the Valley, though their businesses are fewer. St. Edward Roman Catholic Church is the cultural heart of the Filipino community in the Valley.

The Valley neighborhoods lying along Rainier Avenue South rival any other part of Seattle for age, since they are near the historic streetcar (removed in 1937) that in 1892 connected downtown Seattle to Columbia City and then later to Renton, known as the "Rainier Valley and Renton Railroad." The railroad, the reorientation of the Duwamish River and the lowering of Lake Washington, which caused the lake to drain west through Lake Union and the Ship Canal rather than south, made the valley dry enough to allow building, [citation needed] where it boomed along with the rest of Seattle on and after the Alaskan Gold rush right up to the Depression of the 1930s. Because Seattle was a hamlet before the 1889 Alaskan Gold Rush, there is little to distinguish the historic parts of Rainier Valley from other historic neighborhoods in Seattle. Away from Rainier Avenue South, a fair amount of the development is postwar, when the Valley was filled out as part of the "Boeing boom," but historic pre-World War II housing can be found in every part of the Valley, where these often imposing homes once commanded large spreads that were later subdivided and sold off. One such estate was owned from 1902 to 1916 by a certain up-and-coming dry-goods purveyor by the name of J. Walter Nordstrom, who brought up his young family of three children there, as documented by the Rainier Valley Historical Society in 2017 (the estate was at the 3700 block of South Juneau Street). Unlike most of Seattle, then, the Valley has an interesting mix of pre- and post-war houses cheek-to-jowl (in Seattle residential style), with only the neighborhood immediately surrounding Columbia City almost exclusively pre-World War II.

Geography

editThere are several identifiable neighborhoods within Rainier Valley, including (from north to south) "Garlic Gulch" (or the north Valley, from Dearborn to the junction of MLK and Rainier), "Genesee" (from the junction to Alaska), Columbia City (Alaska to Dawson), Hillman City (Dawson to Graham), Brighton (Graham to Kenyon), Dunlap (Kenyon to Cloverdale), and Rainier Beach, which is the only neighborhood in the city where Black Americans make up the majority, at 55%.

The Valley is centered on Rainier Avenue South and Martin Luther King Jr. Way South, its main (northwest- and southeast-bound) thoroughfares. Both Rainier Avenue South and the Valley were named after Mount Rainier, towards which "[t]hrough a fortunate geographic circumstance"[3] the Valley (and hence the street) is oriented. Rainier Avenue South goes through several distinct phases as it winds southeasterly toward Renton, with the north portion being mainly commercial, the central (Columbia City) portion a densely populated historic district, and the southern portion a less dense collection of businesses, apartments, and houses.

Martin Luther King Jr. Way South (usually shortened to "MLK Way"), formerly known as Empire Way (renamed in the 1980s), now carries Seattle's light rail line for the length of the valley until it veers west to serve the North Beacon Hill neighborhood, SoDo industrial area, and downtown Seattle. Light rail and its attendant improvements (most notably underground wiring) have breathed new life into Martin Luther King Jr. Way South, considered at least since the 1970s beset by "social, physical, and economic blight",[4] tracing difficulties to the Boeing bust – hitting hard in Rainier Valley with its high density of factory workers – and exacerbated by the later construction of a freeway interchange that disrupted a once vital commercial district.[5] The construction of light rail brought new residential and commercial development to stations at Columbia City and Othello.[6]

Demographics

editIt is among the most culturally and economically diverse neighborhoods in the Pacific Northwest. The neighborhood's population is 34,241, with Asians making up the largest group (with Filipinos the largest within the Asian population of the Valley). However, there remains a large African American population, as well as European Americans. Its zip code is 98118, which also includes the neighborhood directly east of Rainier Valley of Seward Park. Beacon Hill to the west is largely 98108. "Greater Rainier Valley" can be thought of as including the western slope of Lakewood/Seward Park, and the eastern rise of Beacon Hill.[citation needed]

Rainier Valley's racial breakdown is 20.9% Caucasian, 32% African American, 34.1% Asian, 1% Native American, 1.6% Pacific Islander, 6.5% Mixed Race, and 3.4% from other races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 7.2% of the population. 11.1% of families and 13.9% of the population were below the poverty line.[7] Nearly one quarter of the cities' African-American population resides in Rainier Valley.

Public safety

editBeginning in the 1960s, Rainier Valley began to be viewed as "unsafe," with this view peaking in the 1980s and the Valley did include two housing projects; Rainier Vista and Holly Park. The area is the home of organized gangs with rivalries against each other and groups in other neighborhoods.[8] Of the 28 homicides in Seattle in 2008, six occurred in Rainier Valley.[9]

In 2006, the Seattle Police Department announced that the South Precinct, which includes Rainier Valley had dropped in crime rate by 8% for the first ten months of 2006. Auto thefts and thefts in general had decreased with robbery and gang activity still highly reported.[10]

Economy

editThere are many different areas to purchase food within the neighborhood, with many small delis, bakeries and restaurants.[10]

References

edit- ^ Rainier Valley Historical Society (2012). Rainier Valley. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9780738588971.

- ^ Lyons, William (2002). The Politics of Community Policing; Rearranging the Power to Punish. Michigan: University of Michigan Press. p. 63. ISBN 9780472089017.

- ^ Steinbrueck, Victor (1962). Seattle Cityscape. Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 93.

- ^ SR 90 Final Environmental Impact Statement, United States Department of Transportation and Washington State Department of Transportation, September 22, 1978, FHWA-WN-EIS-75-05-F

- ^ Lyons, William (1999). "Communities and crime on the south side of Skid Road". The Politics of Community Policing. University of Michigan Press. pp. 57–76. ISBN 0472023861. OCLC 39800590.

- ^ Stiles, Marc (December 10, 2013). "Big apartment project in Rainier Valley will be built in phases". Puget Sound Business Journal. Retrieved December 23, 2019.

- ^ "98118". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12.

- ^ Castro, Hector; Reporter, P.-I. (2006-05-30). "Rival gangs might be behind rise in shootings". seattlepi.com. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ McNerthney, Casey (2008-12-31). "A map of 2008 Seattle homicides". Seattle 911 -- A Police and Crime Blog. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ a b Christensen, Maria (2007). Newcomer's Handbook for Moving to and Living in Seattle; Including Bellevue, Redmond, Everett, and Tacoma. Portland, Oregon: First Books. p. 67. ISBN 9780912301730.

External links

edit- Seattle City Clerk's Neighborhood Map Atlas — Rainier Valley

- Rainier Valley through the years, 88 historic Rainier Valley photos from the Seattle Post-Intelligencer