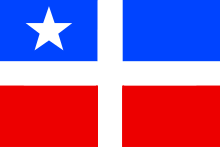

Throughout the history of Puerto Rico, its inhabitants have initiated several movements to gain independence for the island, first from the Spanish Empire between 1493 and 1898 and since then from the United States. Today, the movement is most commonly represented by the flag of the Grito de Lares (Cry of Lares) revolt of 1868.

A spectrum of pro-autonomy, pro-nationalism, and pro-independence sentiments and political parties exist on the island. Since the beginning of the 19th century, organizations advocating independence in Puerto Rico have attempted both peaceful political means as well as violent revolutionary actions to achieve its objectives. The declaration of independence of Puerto Rico occurred on September 23, 1868 during the Grito de Lares revolt against Spanish rule. The revolting members and followers of the Revolutionary Committee of Puerto Rico proclaimed the flag of the revolt as the national flag of an independent “Republic of Puerto Rico”, making it the first flag of Puerto Rico. Since the second half of the 20th century, the independence movement has trailed significantly behind the pro-Commonwealth and pro-statehood movements at the ballots. Independence also received the least support, less than 4.5% of the vote, in the status referendums in 1967 (0.60%), 1993 (4.47%), 1998 (2.6%).

A fourth referendum was held on November 6, 2012, with 54% voting to change Puerto Rico's status but the federal government took no action to do so.[1][2] The fifth plebiscite was held on June 11, 2017, With a voter turnout of 23%, it had the lowest turnout of any status referendum held in Puerto Rico. The independence option was linked to the Commonwealth option, obtaining 1.50%. A sixth referendum was held on November 3, 2020, with 52.52% voting to being a state. A seventh referendum will be held on November 5, 2024.

In the 2020 Puerto Rican general election, the Puerto Rican Independence Party achieved 13.6% of the vote, a significant increase in support from the 2016 Puerto Rican general election when it received only 2.1% of votes.[3][4]

Seeking independence from Spain

editTaíno revolts

editSome Modern Puerto Rican independence movements have claimed historic connection to the 16th century and the Taíno rebellion of 1511 led by Agüeybaná II. In this revolt, Agüeybaná II, the most powerful cacique of the native Taíno people of Puerto Rico at the time, together with Urayoán, cacique of Añasco, organized a revolt in 1511 against the spanish conquistadors in the southern and western parts of the island. He was joined by Guarionex, cacique of Utuado, who attacked the Villa de Sotomayor (Sotomayor Village) in present-day Aguada, killing 80 Spanish settlers.[5] First explorer and governor of Puerto Rico, Juan Ponce de León, led the Spaniards in a series of offensives that culminated in the Battle of Yagüecas.[6] Agüeybaná II's people, who were armed only with spears, bows, and arrows, were no match for the guns of the Spanish forces, resulting in Agüeybaná II being shot and killed in the battle.[7] The revolt ultimately failed, and many Taíno either committed suicide or fled to the interior, mountainous regions of the island.[8][9]

Puerto Rican revolts

editSeveral revolts against the Spanish rulers by the native born, or Criollos, occurred in the 19th century. These include the conspiracy at San Germán in 1809,[10] and the uprisings of people in Ciales, San Germán and Sabana Grande in 1898.[11]

Many Puerto Ricans became inspired by the ideals of Simón Bolívar to liberate South America from Spanish rule. Bolívar sought to create a federation of Latin American nations, to include Puerto Rico and Cuba. Brigadier General Antonio Valero de Bernabé, also known as "The Liberator from Puerto Rico", fought for the independence of South America together with Bolívar; he also wanted an independent Puerto Rico.

María de las Mercedes Barbudo, the first female Puerto Rican Independentista, joined forces with the Venezuelan government, under the leadership of Simón Bolívar, to lead an insurrection against the Spanish colonial forces in Puerto Rico.[12][13] The Spanish occupation forces were the object of more than thirty conspiracies. Some, like the Lares uprising, the riots and sedition of 1897 and the Secret Societies at the end of the 19th century, became popular rebellions. The most widespread popular revolts, however, were the one in Lares in 1868, and the one in Yauco in 1897.

In 1868, the Grito de Lares (Cry of Lares) took place, in which revolutionaries occupied the town of Lares and declared the independence of the Republic of Puerto Rico on September 23, 1868. Ramón Emeterio Betances was the leader of this revolt. Earlier, Segundo Ruiz Belvis and Betances had founded the Comité Revolucionario de Puerto Rico (Revolutionary Committee of Puerto Rico) from their exile in the New York. Betances wrote several Proclamas, or statements attacking the exploitation of the Puerto Ricans by the Spanish colonial system, and called for immediate insurrection. These statements were rapidly circulated throughout the island as local dissident groups began to organize.

Most dissidents were Criollos (born on the island). The critical state of the economy, along with the increasing repression imposed by the Spanish, served as catalysts for the rebellion. The stronghold of the movement were towns located on the mountains of the west of the island. The rebels looted local stores and offices owned by peninsulares (Spanish-born residents) and took over the city hall. They took as prisoners Spanish merchants and local government officials. The revolutionaries placed their revolutionary flag on the high altar of the church to signify that the revolution had begun.[14] The Republic of Puerto Rico was proclaimed, and Francisco Ramírez Medina was proclaimed interim president. The revolutionaries offered immediate freedom to any slave who would join them.

In the next town, San Sebastián del Pepino, the Grito de Lares (Cry of Lares) revolutionaries encountered heavy resistance from the Spanish militia and retreated to Lares. The Spanish militia rounded up the rebels and quickly brought the insurrection to an end. The government imprisoned some 475 rebels, and a military court imposed the death penalty, for treason and sedition, on all the prisoners. But in Madrid, Eugenio María de Hostos and other prominent Puerto Ricans were successful in interceding, and the national government ordered a general amnesty and release of all the prisoners. Numerous leaders, such as Betances, Rojas, Lacroix, Aurelio Méndez and others, were sent into exile.[15]

In 1896, a group of residents of Yauco who supported independence joined forces to overthrow the Spanish government in the island. The group was led by Antonio Mattei Lluberas, a wealthy coffee plantation owner, and Mateo Mercado. Later that year, the local Civil Guard discovered their plans and arrested all those involved. They were soon released and allowed to return home.[16]

In 1897, Lluberas traveled to New York City and visited the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Committee, which included the exiled group from the Grito de Lares (Cry of Lares) revolt of 1868. They made plans for a major coup in Puerto Rico.[17] Lluberas returned to Puerto Rico with the new revolutionary flag of Puerto Rico adopted by the committee in 1895, the current flag of the island, to be flown at the coup.[18] The Mayor of Yauco, Francisco Lluch Barreras, learned of the planned uprising, and notified the island's Spanish governor. When Fidel Velez, one of the separatist leaders, learned that the word was out, he met with other leaders and forced them to begin the insurrection immediately.[18]

On March 24, 1897, Velez and his men marched towards Yauco, planning to attack the barracks of the Spanish Civil Guard, to gain control of their arms and ammunition. At arrival, they were ambushed by Spanish forces. When a firefight broke out, the rebels quickly retreated. On March 26, a group headed by Jose Nicolas Quiñones Torres and Ramon Torres fought Spanish colonial forces (mostly island men) in a barrio called Quebradas of Yauco, but were overcome.[18] The government arrested more than 150 rebels, charged them with various crimes against the state, and sent them to prison in the City of Ponce.[19] These attacks became known as the Intentona de Yauco (Attempted Coup of Yauco). It was the first time that the flag of Puerto Rico was flown on the island.[20][21]

Velez fled to St. Thomas where he lived in exile. Mattei Lluberas went into exile in New York City, joining a group known as the Puerto Rican Commission.[19]

Spanish Charter of Autonomy

editAfter four hundred years of colonial rule by the Spanish Empire, Puerto Rico gained autonomy as an overseas autonomous community of Spain on November 25, 1897 through a Carta de Autonomía (Charter of Autonomy). It was signed by Spanish Prime Minister Práxedes Mateo Sagasta and ratified by the Spanish Cortes.[22][23] The newfound autonomy was short-lived, as Puerto Rico was invaded, occupied, and annexed by the United States during the Spanish-American War in 1898.

Seeking independence from the United States

editThe United States was granted possession of Puerto Rico as part of the Treaty of Paris of 1898, which concluded the Spanish–American War.

After Puerto Rico became an American possession during the Spanish–American War in 1898, Manuel Zeno Gandía traveled to Washington, D.C. where, together with Eugenio María de Hostos, he proposed the idea of independence for Puerto Rico. The men were disappointed when their ideas were rejected by the US government and the island was organized as a US territory. Zeno Gandia returned to the island and continued as an activist.

A number of leaders, including a well-known intellectual and legislator called José de Diego, sought independence from the United States via political accommodation. On June 5, 1900, President William McKinley named De Diego, together with Rosendo Matienzo Cintrón, José Celso Barbosa, Manuel Camuñas, and Andrés Crosas to an Executive Cabinet under U.S.-appointed Governor Charles H. Allen. The Executive Cabinet also included six American members.[24]

Diego resigned from the position in order to pursue independence. On 19 February 1904, he co-founded the Unionist Party, or the Union of Puerto Rico, the first mass party to advocate for independence for Puerto Rico in the form of a sovereign nation, along with Luis Muñoz Rivera, Rosendo Matienzo Cintrón and Antonio R. Barceló.[25][26] Diego was elected to the House of Delegates, the only locally elected body of government then allowed by the U.S., over which Diego presided from 1904 to 1917. The House of Delegates was subject to the U.S. President's veto power and unsuccessfully voted for the island's right to independence and self-government. It petitioned against imposition of U.S. citizenship to Puerto Ricans in 1917, but the US granted citizenship to island residents. Despite these failures, Diego became known as the "Father of the Puerto Rican Independence Movement."[27]

The newly created Puerto Rico Union Party advocated allowing voters to choose among non-colonial options, including annexation, an independent protectorate, and full autonomy. Another new party called the Puerto Rico Independence Party emerged, founded by Rosendo Matienzo Cintrón in 1912, which promoted Puerto Rico's independence. That same year, Scott Colón, Zeno Gandía, Matienzo Cintrón, and Luis Lloréns Torres wrote a manifesto for independence.[28] The Independence Party was the first party in the history of the island to openly support independence from the United States as part of its platform.[24]

American business

editThrough the 1930s, U.S. banking interests and corporations expanded their control of lands throughout Latin America.[29] Taking Puerto Rico was seen as a part of American "Manifest destiny."[30] The American government supported American corporations with military force on occasion. The profits generated by this one-sided arrangement were enormous, as US corporations developed large plantations.[31]

Several years after leaving office, in 1913 Charles H. Allen, the first civilian U.S. governor of Puerto Rico, succeeded to the presidency of the American Sugar Refining Company after serving as treasurer.[32] He resigned in 1915, but stayed on the board. The company operated the largest sugar-refining operation in the world[33] and was later renamed as the Domino Sugar company.[34] According to historian Federico Ribes Tovar, Charles Allen leveraged his governorship of Puerto Rico into a controlling interest over the entire Puerto Rican economy through Domino Sugar.[29][31]

American professor and activist Noam Chomsky argued in the late 20th century that, after 1898 "Puerto Rico was turned into a plantation for U.S. agribusiness, later an export platform for taxpayer-subsidized U.S. corporations, and the site of major U.S. military bases and petroleum refineries."[35] By 1930, over 40 percent of all the arable land in Puerto Rico had been converted into sugar plantations owned by Domino Sugar and U.S. banking interests. These bank syndicates also owned the insular postal system, the coastal railroad, and the San Juan international seaport.[29][31][36]

Formation of the Nationalist Party

editIn 1919, Puerto Rico had two major organizations that supported independence: the Nationalist Youth and the Independence Association. Also in 1919, José Coll y Cuchí, a member of the Union Party of Puerto Rico, left the party and formed the Nationalist Association of Puerto Rico. In 1922, these three political organizations joined forces and formed the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party, with Coll y Cuchi as party president. The party's chief goal was to achieve independence from the United States. This party contended that by international law, the Spanish had no authority under the Treaty of Paris to cede the island, as it was no longer theirs.[22][29] In 1924 Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos joined the party and was named vice-president.

On May 11, 1930, Pedro Albizu Campos was elected president of the Nationalist Party. Under his leadership, in the 1930s the party became the largest independence movement in Puerto Rico. But, after disappointing electoral outcomes and strong repression by the territorial police, by the mid-1930s Albizu opted against the electoral political process. He advocated violent revolution as the means to achieve independence.

In 1932, the pro-independence Liberal Party of Puerto Rico was founded by Antonio R. Barceló. The Liberal Party's political agenda was the same as that of the original Union Party, urging independence for Puerto Rico.[37] Among those who joined him in the "new" party were Felisa Rincón de Gautier and Ernesto Ramos Antonini.

By 1932 Luis Muñoz Rivera's son, Luis Muñoz Marín, had also joined the Liberal Party. Muñoz Marín was eventually the first democratically elected Governor of Puerto Rico.

During the 1932 elections, the Liberal Party faced the Alliance, then a coalition of the Republican Party of Puerto Rico and Santiago Iglesias Pantin's Socialist Party. Barceló and Muñoz Marín were both elected Senators. By 1936, differences between Muñoz Marín and Barceló began to surface, as well as between those followers who considered Muñoz Marín the true leader and those who considered Barceló as their leader.[38]

Muñoz Marín and his followers, who included Felisa Rincón de Gautier and Ernesto Ramos Antonini, held an assembly in the town of Arecibo to found the Partido Liberal, Neto, Auténtico y Completo (Clear, Authentic and Complete Liberal Party), later named the People's Democratic Party (PPD for Spanish name).

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| Newsreel scenes of the Ponce Massacre here |

During the 1930s and 1940s, Nationalist partisans/guerrilleros took part in violent incidents:

- On April 6, 1932, Nationalist partisans marched into the Capitol building in San Juan to protest the legislative proposal to approve the present Puerto Rican flag, the official flag of the insular government. Nationalists preferred the flag used during the Grito de Lares.

- On October 24, 1935, a confrontation with police at University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras campus, killed four Puerto Rican Nationalist Party supporters and one policeman. The event came to be known as the Río Piedras massacre.[39]

- On February 23, 1936, Colonel Elisha Francis Riggs, formerly of the US Army and the highest police officer in the island, was assassinated in retaliation for the Río Piedras events by Nationalists Hiram Rosado and Elías Beauchamp. Rosado and Beauchamp were arrested, and summarily executed without a trial at the police headquarters in San Juan.[40]

- In 1936, the U.S. Senator Millard Tydings presented a legislative proposal to grant independence to Puerto Rico, but many people believed that it had unfavorable economic conditions.[41][42] Barceló and the Liberal Party favored the Bill, because it would give Puerto Rico its independence; Muñoz Marín opposed the Bill because he wanted Puerto Rico's immediate independence but with favorable conditions.[38]

- On March 21, 1937, a march in Ponce by the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party, organized to commemorate the ending of slavery in Puerto Rico, resulted in the deaths of 17 unarmed citizens and 2 policemen at the hands of the territorial police, an event known as the Ponce massacre.

- On July 25, 1938, shots were fired at the US colonial governor, Blanton Winship during a parade; they killed Police Colonel Luis Irizarry. Soon afterward, two Nationalist partisans/guerrilleros attempted to assassinate Robert Cooper, judge of the Federal Court in Puerto Rico. Winship tried to suppress the Nationalists.

- On June 10, 1948, the United States-appointed Governor of Puerto Rico, Jesús T. Piñero, signed into law a bill passed by the Puerto Rican Senate, which was controlled by elected PPD representatives. It prohibited discussion of independence, militant independence activism, and significantly curtailed other Puerto Rican independence activities. The Ley de la Mordaza (Gag Law) also made it illegal to sing a patriotic song, and reinforced the 1898 law that had made it illegal to display the Flag of Puerto Rico, with anyone found guilty of disobeying the law in any way being subject to a sentence of up to ten years imprisonment, a fine of up to US$10,000 (equivalent to $127,000 in 2023), or both.

Events under Commonwealth status

edit| External videos | |

|---|---|

| Newsreel scenes in Spanish of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party revolts of the 1950s here |

The Puerto Rican independence movement took new measures after the Free Associate State was authorized. On October 30, 1950, with the new autonomist Commonwealth status about to go into effect, multiple Nationalist uprisings occurred, in an effort to focus world attention on the Movement's dissatisfaction with the new commonwealth status.

They catalyzed roughly a dozen skirmishes throughout Puerto Rico including Peñuelas,[43] the Jayuya Uprising,[44] the Utuado Uprising, the San Juan Nationalist revolt, and other shootouts in Mayagüez, Naranjito, and Arecibo. During the 1950 Jayuya Uprising, Blanca Canales declared Puerto Rico a free republic. Two days after the creation of the Commonwealth, two Nationalists attempted to assassinate US President Harry S. Truman in Washington, DC.

Acknowledging the importance of the question of Puerto Rican status, Truman supported a plebiscite in Puerto Rico in 1952 on the new constitution, to determine the status of the island's relationship to the U.S.[45] The people voted by nearly 82% in favor of the new constitution and Free Associated State, or Commonwealth.[46] Nationalists criticized the constitution because the Commonwealth was subject to US laws and to approval by the US executive and legislative branches of government, branches which Puerto Ricans did not participate in electing. As the government suppressed the Nationalist leaders, their political activities and influence waned.[47]

In the 1954 United States Capitol shooting incident, four nationalists opened fire on US Representatives during a debate on the floor of the US Congress, wounding five men, one seriously. The Nationalists were tried and convicted in federal court and sentenced effectively to life imprisonment. In 1978 and 1979, their sentences were commuted by President Jimmy Carter to time served, and they were allowed to return to Puerto Rico.

In the 1960s, the United States received international condemnation for holding onto the world's oldest colony.[48] By the 1960s, a new phase of the Puerto Rican independence movement began. Several organizations began to use "clandestine armed struggle" against the US government. Underground "people's armies" such as Movimiento Independentista Revolucionario en Armas (MIRA, in english: Revolutionary Independence Movement in Arms),[49] Comandos Armados de Liberación (CAL, in english: Armed Liberation Commands),[50] Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional (FALN, in english: Armed Forces of National Liberation), Organización de Voluntarios por la Revolución Puertorriqueña (OVRP, in english: Organization of Volunteers for the Puerto Rican Revolution),[51] The Ejército Popular Boricua (EPB, in english: Boricua Popular Army), and others began engaging in subversive activities against the US government and military to bring attention to the colonial condition of Puerto Rico. In 1977, Rubén Berríos Martínez, then the President of the Puerto Rican Independence Party, wrote a long and detailed article in Foreign Affairs that declared that the 'only solution' was independence for Puerto Rico.[52]

In January 2025, the CIA admitted in a declassified document that it had collected information on Puerto Rican independence groups at the request of Democratic congressmen, the Central Intelligence Agency probed for links to the Cuban government, and Puerto Rican independence movements in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s[53].

Political support

editA number of social groups, political parties, and individuals worldwide have supported the concept of Puerto Rican independence. On the island itself, it is a fringe but intense movement, with The Washington Post reporting that "calls for Puerto Rico's independence have existed since the days of Spanish colonial rule and continued after the United States seized control of the island in 1898 (...) although many Puerto Ricans express deep patriotism for the island, the independence impulse has never translated in the polls."[54]

The Democratic Party in the United States asserted in its 2012 platform that it "will continue to work on improving Puerto Rico's economic status by promoting job creation, education, health care, clean energy, and economic development on the Island."[55] The Republican Party asserts that it "support[s] the right of the United States citizens of Puerto Rico to be admitted to the Union as a fully sovereign state if they freely so determine," that Congress should "define the constitutionally valid options for Puerto Rico" to gain permanent non-territorial status, and said that, while Puerto Rico's status should be supported by a referendum sponsored by "the U.S. government."[56] Neither of the two major parties in Puerto Rico supports independence: the Popular Democratic Party supports the current status of Puerto Rico as a self-governing unincorporated territory, and the New Progressive Party of Puerto Rico supports statehood.

Minority parties have expressed different positions: in 2005, Communist Party USA passed a resolution about Puerto Rico, condemning American imperialism, while stating that "the Communist Party of the USA continues its support for independence of Puerto Rico and the transfer of all sovereign powers to Puerto Rico."[57] Their platform supported the people's "acquisition of their internationally recognized right to independence and self-determination ..."[58] In 2012, the Green Party of the United States had a platform supporting independence.[59] Socialist Party USA does not support independence for Puerto Rico, but calls for "full representation for the U.S. territories of Guam and Puerto Rico, all Native American reservations, and the District of Columbia."[60]

During the summit of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States in Havana, Cuba in January 2014, Nicolas Maduro, the President of Venezuela, told The Wall Street Journal that he supported Puerto Rican independence, saying that "it's an embarrassment that Latin America and the Caribbean in the 21st century still have colonies. Let the imperial elites of the U.S. say whatever they want."[61][62] Also at this summit, the president of Argentina, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, pledged to vote for independence of Puerto Rico; and Raúl Castro "called for an independent Puerto Rico."[61]

Other individuals and groups supporting Puerto Rican independence have included: poet Martín Espada, professor and writer Jason Ferreira, the group Calle 13, FALN leader Oscar López Rivera, Roberto Barreto, a member of Organizacion Socialista Internacional; Puerto Rican nationalist Carlos Alberto Torres, and US Representative Luis Gutiérrez.[63][64][65][66][67][68]

In March 2023, Cuba reiterated its commitment to self-determination and independence of the people of Puerto Rico.[69]

20th century to present

editLevinson and Sparrow in their 2005 book suggest the Foraker Act (Pub. L. 56–191, 31 Stat. 77, enacted April 12, 1900), and the Jones–Shafroth Act (Pub. L. 64–368, 39 Stat. 951, enacted March 2, 1917) reduced political opposition in the island, as they vested the U.S. Congress with authority and veto power over any legislation or referendum initiated by Puerto Rico.[70][71]

Founded in 1922, the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party worked for independence. In 1946, Gilberto Concepción de Gracia founded the Puerto Rican Independence Party (PIP). It has continued to participate in the island's electoral process.

In the mid-century, the "Cointelpro program" was a project conducted by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to surveil, infiltrate, discredit, and disrupt domestic political organizations which it classified as suspect or subversive. The police documented thousands of extensive carpetas (files) concerning individuals of all social groups and ages. Approximately 75,000 persons were listed as under political police surveillance. Historians and critics found that the massive surveillance apparatus was directed primarily against Puerto Rico's independence movement. As a result, many independence supporters moved to the Popular Democratic Party to support its opposition to statehood.[72]

In the 21st century, a majority of Independentistas seek to achieve independence either through peaceful political means or violent revolutionary actions. The Independence Party has elected some legislative candidates, but in recent elections has not won more than a small percentage of votes for its gubernatorial candidates (2.04% in 2008) or the legislative elections (4.5-5% of the island-wide legislative vote in 2008).[73]

In March 2023, a diaspora group petitioned the United States Congress to create an American-Puerto Rican Commission to promote the decolonization and independence of Puerto Rico from the United States of America.[74]

In April 2023, Puerto Rico's Status Act, which seeks to resolve its territorial status and relationship with the United States through a binding plebiscite at the federal level, was reintroduced in the House by Democrats.[1].

United Nations' view

editSince 1953, the United Nations has been considering the Political status of Puerto Rico and how to assist it in achieving "independence" or "decolonization". In 1978, the Special Committee determined that a "colonial relationship" existed between the US and Puerto Rico.[75]

Note that the UN's Special Committee has often referred to Puerto Rico as a nation in its reports, because, internationally, the people of Puerto Rico are often considered to be a Caribbean nation with their own national identity.[76][77][78] Most recently, in a June 2016 report, the Special Committee called for the United States to expedite the process to allow self-determination in Puerto Rico. More specifically, the group called on the United States to expedite a process that would allow the people of Puerto Rico to exercise fully their right to self-determination and independence: "allow the Puerto Rican people to take decisions in a sovereign manner, and to address their urgent economic and social needs, including unemployment, marginalization, insolvency and poverty".[79]

2012 status referendum

editThe main political parties in Puerto Rico have supported a continuing relationship with the United States and been supported by the electorate. By the 1940s, voters had elected a majority of Partido Popular Democrático (PPD) members in the legislature. In 1952, they voted by nearly 82% in support of the new constitution of the Estado Libre Associado or Commonwealth.

Sixty years later, a majority of those who voted on the second question of a 2012 referendum, to indicate what type of arrangement they preferred, voted to seek admission as a state into the United States. 61.16% voted for statehood, 33.34% voted for free association and 5.49% voted for independence. Hundreds of thousands of voters abstained from the question, so the proportion of voters for statehood was actually 45% of the total eligible electorate rather than a majority.[80]

In a status referendum in 2012, which had a two-part vote, 5.5% voted for independence.[1][2] Analysts noted that the results were ambiguous because of issues related to the structure of questions and supporters of the commonwealth status urging voters to abstain from voting on the second question. Journalist Roque Planas, co-founder of the Latin American News Dispatch, wrote as an editor in HuffPost:

the referendum consisted of two questions. First, it asked voters if they wanted to keep their current U.S. commonwealth status. Dissatisfaction emerged victorious with 52 percent of the vote. The referendum then asked if voters wanted to become a U.S. state, an independent country, or a freely associated state -- a type of independence in close alliance with the United States. Some 61 percent of those who answered the second question chose statehood. That 61 percent wasn't the majority, however. Over 470,000 voters intentionally left the second question blank, meaning that only 45 percent of those casting ballots supported statehood.[81]

Similarly, as reported by the New York Daily News, Juan Gonzalez, journalist and a co-host of the TV show Democracy Now! said:

the referendum on the island's future was, in fact, a two-part vote that actually revealed that most want an end to the status quo, but not necessarily statehood ... And the results were: 809,000 votes for statehood, only 73,000 for independence, and 441,000 for sovereign free association ... So statehood did not actually receive 61% of the vote — until you ignore the nearly half a million people who cast blank ballots.[82]

In October 2013, The Economist reported on the island economy's "dire financial straits."[83] Referring to the 2012 referendum, it said that "Puerto Rico is unlikely to become a state any time soon. Because the island remains a territory, the decision is ultimately out of boricuas' hands ... the legislature is highly unlikely to prioritise a Puerto Rican statehood bill ... the Republican Party would surely use every tactic at its disposal to block a statehood bill," as the island voters have been overwhelmingly supportive of Democratic Party presidential candidates and could be expected to vote for the same party for Congressional seats if statehood were approved by Congress.[83]

The Washington Post reported in December 2013 that, since Puerto Ricans became US citizens in 1917, they have "been divided over their relationship with the mainland" on whether to become a US state, become independent, or a self-governing territory under US control.[84]

2017 status referendum

editThe previous plebiscites provided voters with three options: statehood, free association, and independence. The 2017 referendum offered three options: Statehood, Commonwealth and Independence/Free Association. If the majority vote for the latter, a second vote will be held to determine the preference: full independence as a nation or associated free state status with independence but with a "free and voluntary political association" between Puerto Rico and the United States.[85]

The White House Task Force on Puerto Rico offers the following specifics: "Free Association is a type of independence. A compact of Free Association would establish a mutual agreement that would recognize that the United States and Puerto Rico are closely linked in specific ways as detailed in the compact. Compacts of this sort are based on the national sovereignty of each country, and either nation can unilaterally terminate the association."[86] The content of the Compact of Free Association might cover topics such as the role of the US military in Puerto Rico, the use of the U.S. currency, free trade between the two entities, and whether Puerto Ricans would be U.S. citizens.[87]

Former Governor Ricardo Rosselló was strongly in favor of statehood to help develop the economy and help to "solve our 500-year-old colonial dilemma ... Colonialism is not an option . ... It's a civil rights issue ... 3.5 million citizens seeking an absolute democracy," he told the news media.[88] Benefits of statehood include an additional $10 billion per year in federal funds, the right to vote in presidential elections, higher Social Security and Medicare benefits, and a right for its government agencies and municipalities to file for bankruptcy. The latter is currently prohibited.[89]

At approximately the same time as the referendum, Puerto Rico's legislators voted on a bill that allows the Governor to draft a state constitution and hold elections to choose senators and representatives to the federal Congress. Regardless of the outcome of the 2017 referendum and the bill, action by the United States Congress will be necessary to implement changes to the status of Puerto Rico under the Territorial Clause of the United States Constitution.[89]

Online rise in reunification with Spain

editIn recent years, primarily in online spaces, there has been a growth in support for reunification with Spain rather than statehood, in what is known as Hispanism.[90]

See also

edit- Puerto Rico Democracy Act of 2007

- Latin American and Caribbean Congress in Solidarity with Puerto Rico's Independence

- Latin America-United States relations

- Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional (Puerto Rico)

- Puerto Rico statehood movement

- Proposed political status for Puerto Rico

- Sovereigntism (Puerto Rico)

- Special Committee on Decolonization

- United Nations list of non-self-governing territories

- Falange Boricua

- Movimento Nacional Sindicalista de Puerto Rico

References

edit- ^ a b "CEE Event - CONDICIÓN POLÍTICA TERRITORIAL ACTUAL - Resumen" (in Spanish). Comisión Estatal de Elecciones de Puerto Rico. 2012-11-08. Archived from the original on 2012-11-09. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- ^ a b "CEE Event - OPCIONES NO TERRITORIALES - Resumen" (in Spanish). Comisión Estatal de Elecciones de Puerto Rico. 2012-11-08. Archived from the original on 2012-11-09. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- ^ "Is Statehood Next for Puerto Rico? It's Complicated". Medium. 2021-04-08. Archived from the original on 2021-04-10. Retrieved 2021-04-11.

- ^ ""A Tremendous Jump for Progressive Forces": Puerto Rico Election Signals End of Two-Party Dominance". Democracy Now. 2020-11-20. Archived from the original on 2021-04-14. Retrieved 2021-04-11.

- ^ Puerto Rico Reconstruction Administration (1940). "History from Puerto Rico: A Guide to the Island of Boriquén". The University Society. Archived from the original on 2007-11-05. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

- ^ "A Historical Overview of Colonial Puerto Rico: The Importance of San Juan as a Military Outpost". Archived from the original on 2009-05-31. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Smithsonian Institution (1907). Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology. Harvard University. p. 38. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

Urayoán.

- ^ "Land Tenure Development in Puerto Rico" Archived 2006-09-13 at the Wayback Machine, University of Maine

- ^ "Puerto Rico's First People" Archived 2007-12-31 at the Wayback Machine, Extra News website

- ^ Schwab, Gail M. The French Revolution of 1789 and Its Impact. Greenwood Publishing Group, 1995. ISBN 978-0-313-29339-9. p. 268

- ^ Ayala, César J. Puerto Rico in the American Century: A History Since 1898, UNC Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-8078-3113-7. P.343

- ^ "María de las Mercedes - La primera Independentista Puertorriquena" Archived 2011-04-21 at the Wayback Machine, 80 Grados

- ^ Meaning of "Independentista" Archived 2012-03-26 at the Wayback Machine, Spanish-English Dictionary

- ^ The Women from Puerto Rico. Mariana Bracetti Archived 2011-06-11 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on September 26, 2007.

- ^ "Grito de Lares" Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine, Puerto Rico Encyclopedia

- ^ Héctor Andrés Negroni, Historia militar de Puerto Rico;Pages: 305-06; Publisher: Sociedad Estatal Quinto Centenario (1992); Language: Spanish; ISBN 978-84-7844-138-9

- ^ "Noticias de la XVII Brigada Juan Rius Rivera en Cuba".[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c "Historia militar de Puerto Rico"; by Héctor Andrés Negroni (Author); Pages: 307; Publisher: Sociedad Estatal Quinto Centenario (1992); Language: Spanish; ISBN 978-84-7844-138-9

- ^ a b "1898 La Guerra Hispano Americana". www.proyectosalonhogar.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- ^ Sabia Usted? Archived 2000-12-08 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish), Sabana Grande, Retrieved Feb. 25, 2009

- ^ The Flag Archived 2017-07-04 at the Wayback Machine, Flags of the World, Retrieved Feb. 25, 2009

- ^ a b Maldonado-Denis, Manuel; Puerto Rico: A Socio-Historic Interpretation, pp.46-62; Random House, 1972

- ^ Ribes Tovar et al., p.106-109

- ^ a b Chronology of Puerto Rico in the Spanish–American War Archived 2018-01-04 at the Wayback Machine, Library of Congress

- ^ "José de Diego - Library of Congress". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 11 July 2018. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ Bolivar Pagan. Historia de los Partidos Políticos Puertorriqueños (1898-1956). San Juan, Puerto Rico: Litografía Real Hermanos, Inc. 1959. Tomo I. p. 114.

- ^ Articulos Archived 2007-02-03 at the Wayback Machine (Spanish)

- ^ Luis Llorens Torres Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d Ribes Tovar et al., p.122-144

- ^ Dyreson, Mark; Mangan, J.A.; Park, Roberta J. (13 September 2013). Mapping an Empire of American Sport. Routledge. ISBN 9781317980360. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ^ a b c Maldonado-Denis, Manuel; Puerto Rico: A Socio-Historic Interpretation, pp.52-83; Random House, 1972

- ^ Charles H. Allen Resigns" Archived 2020-02-01 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, 16 June 1915, accessed 2 November 2013

- ^ Ayala, Cesar; American Sugar Kingdom: The Plantation Economy of the Spanish Caribbean 1898-1934, pp. 45-47; University of North Carolina Press, 1999

- ^ Arrington, Leonard J.; Beet sugar in the West; a history of the Utah-Idaho Sugar Company, 1891-1966; University of Washington Press, 1966.

- ^ Noam Chomsky, "A Century Later" Archived 2014-02-22 at the Wayback Machine, Peace Review, September 1998

- ^ Ayala, Cesar; American Sugar Kingdom: The Plantation Economy of the Spanish Caribbean 1898-1934, pp.221-227; University of North Carolina Press, 1999

- ^ "Antonio Barcelo". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2014 – via angelfire.com.

- ^ a b Puerto Rico Por Encima de Todo: Vida y Obra de Antonio R. Barceló, 1868-1938; by: Dr. Delma S. Arrigoitia; Page 292; Publisher: Ediciones Puerto (January 2008); ISBN 978-1-934461-69-3

- ^ "19 Were killed including 2 policemen caught in the cross-fire" Archived 2012-11-22 at the Wayback Machine, The Washington Post 28 December 1999; p. A03. "Apology Isn't Enough for Puerto Rico Spy Victims." Retrieved July 8, 2009, hosted at Latin American Studies website.

- ^ The Puerto Ricans: a documentary history, Markus Wiener Publishers, 2008P179

- ^ Strategy as Politics; by Jorge Rodriguez Beruff; Publisher: Universidad de Puerto Rico; pg. 178; ISBN 0-8477-0160-3

- ^ Bosque Pérez, Ramón (2006). Puerto Rico Under Colonial Rule. SUNY Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-7914-6417-5. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ^ El ataque Nacionalista a La Fortaleza; by Pedro Aponte Vázquez; Page 7; Publisher: Publicaciones RENÉ; ISBN 978-1-931702-01-0

- ^ "NY Latino Journal". Archived from the original on 26 August 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ Hunter, Stephen; Bainbridge, John Jr. (2005). American Gunfight: The Plot To Kill Harry Truman – And The Shoot-Out That Stopped It. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 4, 251. ISBN 978-0-7432-6068-8.

- ^ Nohlen, D (2005) Elections in the Americas: A Data Handbook, Volume I, p. 556 ISBN 9780199283576

- ^ FBI Files on Puerto Ricans Archived 2005-03-07 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 2008-12-04

- ^ Navarro, Sharon Ann, and Mejia, Armando Xavier. Latino Americans and Political Participation, Santa Barbara, California: ABC–CLIO, 2004. ISBN 978-1-85109-523-0. p. 106.

- ^ "Movimiento Independentista Revolucionario en Armas (MIRA) - Case # SJ-100-12315. Retrieved on 2008-12-04". Archived from the original on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ http://www.start.umd.edu/data/tops/terrorist_organization_profile.asp?id=3947 Terrorist Organization Profile: Armed Commandos of Liberation. Retrieved on 2008-12-04

- ^ Bosque Pérez, Ramón. Puerto Rico Under Colonial Rule: Political Persecution and the Quest for Human Rights. SUNY Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0-7914-6417-5. P.8.

- ^ Martinez, Ruben Berrios (April 1977). "Independence for Puerto Rico: The Only Solution". foreignaffairs.com. Archived from the original on 23 January 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ https://www.elnuevodia.com/corresponsalias/washington-dc/notas/la-cia-admitio-que-recopilo-informacion-sobre-grupos-independentistas-de-puerto-rico/ La CIA admitió que recopiló información sobre grupos independentistas de Puerto Rico. Retrieved on 2025-01-07

- ^ Paul Lewis, "Recruiting For Iraq War Undercut in Puerto Rico" Archived 2017-05-23 at the Wayback Machine, Washington Post, 18 August 2007

- ^ "Moving America Forward: 2012 Democratic National Platform" (PDF). dstatic.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-15. Retrieved 2014-02-24.

- ^ "We Believe in America: 2012 Republican Platform" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-07-30. Retrieved 2014-02-22.

- ^ "Communist Party, USA: Resolution on Puerto Rico". cpusa.org. 20 July 2005. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "CPUSA Program: Multiracial, Multinational Unity for Full Equality and Against Racism: Core Forces for Progress". cpusa.org. Archived from the original on 7 December 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "2012 Green Party Platform: Puerto Rican Independence". gp.org. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "Platform - Socialist Party USA". SocialistParty-USA.net. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ a b "Americas Summit Sans United States: Venezuela, Argentina To Push For Puerto Rican Independence January 28, 2014". Fox News Latino. Archived from the original on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "Venezuelan Leader to Press for Puerto Rican Independence" Archived 2016-03-11 at the Wayback Machine, Wall Street Journal, 26 January 2014.

- ^ "Puerto Rico still deserves independence" Archived 2014-02-25 at the Wayback Machine, Progressive

- ^ "Research Justice: Decolonizing Knowledge, Building Power" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-26.

- ^ "Calle 13’s René "Residente" Pérez on Revolutionary Music, WikiLeaks & Puerto Rican Independence" Archived 2014-02-21 at the Wayback Machine, Democracy Now!

- ^ "Oscar Lopez Rivera: Imprisoned for Supporting Puerto Rican Independence" Archived 2014-02-27 at the Wayback Machine, Dissident Voice

- ^ "Who will determine Puerto Rico's future status?". isreview.org. Archived from the original on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "The Future Of Puerto Rico's Independence Movement". citylimits.org. 29 July 2010. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "Cuba repeats commitment to a just, supportive and sustainable world". Prensa Latina - Latin American News Agency. 25 March 2023. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ Sanford Levinson and Bartholomew H. Sparrow, The Louisiana Purchase and American Expansion: 1803-1898, New York: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2005; pp.66, 178. ("U.S. citizenship was extended to residents of Puerto Rico by virtue of the Jones Act, chap. 190, 39 Stat. 951 (1971) (codified at 48 U.S.C. § 731 (1987))")

- ^ "Race Space and the Puerto Rican citizenship" Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine, University of Dayton

- ^ "Puerto Rico Votes on Status: A Primer on Independence". Archived from the original on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "2008 Election Results (Spanish)". Archived from the original on 2009-10-11. Retrieved 2009-10-06.

- ^ "Grupo de la diáspora pide al Congreso crear una comisión estadounidense boricua para promover la descolonización". 15 March 2023. Archived from the original on 15 March 2023. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- ^ López, Ana M. (2014). "Puerto Rico at the United Nations". The North American Congress on Latin America. The North American Congress on Latin America. Archived from the original on February 22, 2017. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- ^ United Nations. General Assembly. Special Committee on the Situation With Regard to the Implementation of the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples (1971). Report of the Special Committee on the Situation with Regard to the Implementation of the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples. Vol. 23. United Nations Publications. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-92-1-810211-9.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "XIV Ministerial Conference of the Movement of Non-Aligned Nations. Durban, South Africa, 2004. See pages 14–15" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-07-31.

- ^ United Nations. General Assembly. Special Committee on the Situation With Regard to the Implementation of the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples (1971). Report of the Special Committee on the Situation with Regard to the Implementation of the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples. Vol. 23. United Nations Publications. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-92-1-810211-9.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Special Committee on Decolonization Approves Text Calling upon United States Government to Expedite Self-Determination Process for Puerto Rico". United Nations. United Nations. June 20, 2016. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- ^ Puerto Rico Election Code for the 21st Century (PDF) (78, 2.003(54)). 2011. Retrieved August 10, 2014. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 21, 2014. Retrieved January 9, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Roque Planas, "Puerto Rico Statehood: 5 Reasons Why The Island Won't Become The 51st State" Archived 2017-10-07 at the Wayback Machine, HuffPost

- ^ "Puerto Rico referendum historic, but complex: 809,000 vote for statehood, only 73,000 for independence, and 441,000 for sovereign free association" Archived 2014-02-26 at the Wayback Machine, New York Daily News

- ^ a b "The Economist explains" blog: D.R., "Could Puerto Rico become America's 51st state?" Archived 2013-12-24 at the Wayback Machine, The Economist, October 2013

- ^ "Statehood remains an uneasy question for Puerto Ricans". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 13 July 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "What's a Free Associated State?". Puerto Rico Report. Puerto Rico Report. February 3, 2017. Archived from the original on February 24, 2017. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- ^ "What's a Free Associated State?". Puerto Rico Report. Puerto Rico Report. February 3, 2017. Archived from the original on February 24, 2017. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- ^ "Puerto Rico Statehood, Independence, or Free Association Referendum (2017)". Ballotpedia. BALLOTPEDIA. February 6, 2017. Archived from the original on May 6, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

With my vote, I make the initial request to the Federal Government to begin the process of the decolonization through: (1) Free Association: Puerto Rico should adopt a status outside of the Territory Clause of the Constitution of the United States that recognizes the sovereignty of the People of Puerto Rico. The Free Association would be based on a free and voluntary political association, the specific terms of which shall be agreed upon between the United States and Puerto Rico as sovereign nations. Such agreement would provide the scope of the jurisdictional powers that the People of Puerto Rico agree to confer to the United States and retain all other jurisdictional powers and authorities. Under this option the American citizenship would be subject to negotiation with the United States Government; (2) Proclamation of Independence, I demand that the United States Government, in the exercise of its power to dispose of territory, recognize the national sovereignty of Puerto Rico as a completely independent nation and that the United States Congress enact the necessary legislation to initiate the negotiation and transition to the independent nation of Puerto Rico. My vote for Independence also represents my claim to the rights, duties, powers, and prerogatives of independent and democratic republics, my support of Puerto Rican citizenship, and a "Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation" between Puerto Rico and the United States after the transition process

- ^ Wyss, Jim. "Will Puerto Rico become the newest star on the American flag?". Miami Herald. Miami. Archived from the original on February 25, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

- ^ a b Coto, Danica (February 3, 2017). "Puerto Rico gov approves referendum in quest for statehood". Washington Post. DC. Archived from the original on February 4, 2017. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- ^ Kassam, Ashifa (2015-08-30). "Puerto Rico movement pitches solution to economic woes: rejoin Spain". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-07-19.

Further reading

edit- Historia del Movimiento Pro Independencia--antecesor historico del MINH. Wilma E. Reverón Collazo. Introducción a la historia del MPI en el 160 Aniversario del Natalicio de Eugenio María de Hostos. Capaprieto /Movimiento Independentista Nacional Hostosiano - Mayagüez. Mayagüez, Puerto Rico. 11 January 1999. Retrieved 4 Juna 2011.

- Go, J. (2000). "Chains of Empire, Projects of State: Political Education and U.S. Colonial Rule in Puerto Rico and the Philippines." Comparative Studies in Society and History, 42(2), 333-362.

- Mireya Navarro (November 28, 2003). "New Light on Old F.B.I. Fight; Decades of Surveillance of Puerto Rican Groups". The New York Times.