This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

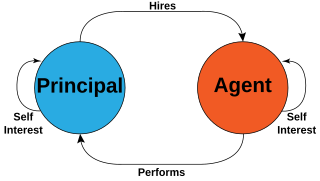

The principal–agent problem refers to the conflict in interests and priorities that arises when one person or entity (the "agent") takes actions on behalf of another person or entity (the "principal").[1] The problem worsens when there is a greater discrepancy of interests and information between the principal and agent, as well as when the principal lacks the means to punish the agent.[2] The deviation from the principal's interest by the agent is called "agency costs".[3]

Common examples of this relationship include corporate management (agent) and shareholders (principal), elected officials (agent) and citizens (principal), or brokers (agent) and markets (buyers and sellers, principals).[4] In all these cases, the principal has to be concerned with whether the agent is acting in the best interest of the principal. Principal-agent models typically either examine moral hazard (hidden actions) or adverse selection (hidden information).[5]

The principal–agent problem typically arises where the two parties have different interests and asymmetric information (the agent having more information), such that the principal cannot directly ensure that the agent is always acting in the principal's best interest, particularly when activities that are useful to the principal are costly to the agent, and where elements of what the agent does are costly for the principal to observe.

The agency problem can be intensified when an agent acts on behalf of multiple principals (see multiple principal problem).[6][7] When multiple principals have to agree on the agent's objectives, they face a collective action problem in governance, as individual principals may lobby the agent or otherwise act in their individual interests rather than in the collective interest of all principals.[8] The multiple principal problem is particularly serious in the public sector.[6][9][10]

Various mechanisms may be used to align the interests of the agent with those of the principal. In employment, employers (principal) may use piece rates/commissions, profit sharing, efficiency wages, performance measurement (including financial statements), the agent posting a bond, or the threat of termination of employment to align worker interests with their own.

Overview

editThe principal's interests are expected to be pursued by the agent; however, when the interests of the agent and principal differ, a dilemma arises. The agent possesses resources such as time, information, and expertise that the principal lacks. At the same time, the principal does not have control over the agent's ability to act in the agent's own best interests. In this situation, the theory posits that the agent's activities are diverted from following the principal's interests and drive the agent to maximize the agent's interests instead.[11]

The principal and agent theory emerged in the 1970s from the combined disciplines of economics and institutional theory. There is some contention as to who originated the theory, with theorists Stephen Ross and Barry Mitnick both claiming authorship.[12] Ross is said to have originally described the dilemma in terms of a person choosing a flavor of ice-cream for someone whose tastes they do not know (Ibid). The most cited reference to the theory, however, comes from Michael C. Jensen and William Meckling.[13] The theory has come to extend well beyond economics or institutional studies to all contexts of information asymmetry, uncertainty and risk.

In the context of law, principals do not know enough about whether (or to what extent) a contract has been satisfied, and they end up with agency costs. The solution to this information problem—closely related to the moral hazard problem—is to ensure the provision of appropriate incentives so agents act in the way principals wish.[citation needed]

In terms of game theory, it involves changing the rules of the game so that the self-interested rational choices of the agent coincide with what the principal desires. Even in the limited arena of employment contracts, the difficulty of doing this in practice is reflected in a multitude of compensation mechanisms and supervisory schemes, as well as in critique of such mechanisms as e.g., Deming (1986) expresses in his Seven Deadly Diseases of management.

Employment contract

editThis section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

In the context of the employment contract, individual contracts form a major method of restructuring incentives, by connecting as closely as optimal the information available about employee performance, and the compensation for that performance. Because of differences in the quantity and quality of information available about the performance of individual employees, the ability of employees to bear risk, and the ability of employees to manipulate evaluation methods, the structural details of individual contracts vary widely, including such mechanisms as "piece rates, [share] options, discretionary bonuses, promotions, profit sharing, efficiency wages, deferred compensation, and so on."[14] Typically, these mechanisms are used in the context of different types of employment: salesmen often receive some or all of their remuneration as commission, production workers are usually paid an hourly wage, while office workers are typically paid monthly or semimonthly (and if paid overtime, typically at a higher rate than the hourly rate implied by the salary).[citation needed] The way in which these mechanisms are used is different in the two parts of the economy which Doeringer and Piore called the "primary" and "secondary" sectors (see also dual labour market).

The secondary sector is characterised by short-term employment relationships, little or no prospect of internal promotion, and the determination of wages primarily by market forces. In terms of occupations, it consists primarily of low or unskilled jobs, whether they are blue-collar (manual-labour), white-collar (e.g., filing clerks), or service jobs (e.g., waiters). These jobs are linked by the fact that they are characterized by "low skill levels, low earnings, easy entry, job impermanence, and low returns to education or experience." In a number of service jobs, such as food service, golf caddying, and valet parking jobs, workers in some countries are paid mostly or entirely with tips.

The use of tipping is a strategy on the part of the owners or managers to align the interests of the service workers with those of the owners or managers; the service workers have an incentive to provide good customer service (thus benefiting the company's business), because this makes it more likely that they will get a good tip.

The issue of tipping is sometimes discussed in connection with the principal–agent theory. "Examples of principals and agents include bosses and employees ... [and] diners and waiters." "The "principal–agent problem", as it is known in economics, crops up any time agents aren't inclined to do what principals want them to do. To sway them [(agents)], principals have to make it worth the agents' while ... [in the restaurant context,] the better the diner's experience, the bigger the waiter's tip."[15] "In the ... language of the economist, the tip serves as a way to reduce what is known as the classic "principal–agent" problem." According to "Videbeck, a researcher at the New Zealand Institute for the Study of Competition and Regulation[,] '[i]n theory, tipping can lead to an efficient match between workers' attitudes to service and the jobs they perform. It is a means to make people work hard. Friendly waiters will go that extra mile, earn their tip, and earn a relatively high income...[On the other hand,] if tipless wages are sufficiently low, then grumpy waiters might actually choose to leave the industry and take jobs that would better suit their personalities.'"[16]

As a solution to the principal–agent problem, though, tipping is not perfect. In the hopes of getting a larger tip, a server, for example, may be inclined to give a customer an extra large glass of wine or a second scoop of ice cream. While these larger servings make the customer happy and increase the likelihood of the server getting a good tip, they cut into the profit margin of the restaurant. In addition, a server may dote on generous tippers while ignoring other customers, and in rare cases harangue bad tippers.

Non-financial compensation

editPart of this variation in incentive structures and supervisory mechanisms may be attributable to variation in the level of intrinsic psychological satisfaction to be had from different types of work. Sociologists and psychologists frequently argue that individuals take a certain degree of pride in their work, and that introducing performance-related pay can destroy this "psycho-social compensation", because the exchange relation between employer and employee becomes much more narrowly economic, destroying most or all of the potential for social exchange. Evidence for this is inconclusive—Deci (1971), and Lepper, Greene and Nisbett (1973) find support for this argument; Staw (1989) suggests other interpretations of the findings.

Incentive structures as mentioned above can be provided through non-monetary recognition such as acknowledgements and compliments on an employee (agent) in place of employment. Research conducted by Crifo and Diaye (2004) [17] mentioned that agents who receive compensations such as praises, acknowledgement and recognition help to define intrinsic motivations that increase performance output from the agents thus benefiting the principal.

Furthermore, the studies provided a conclusive remark that intrinsic motivation can be increased by utilising the use of non-monetary compensations that provide acknowledgement for the agent. These higher rewards, can provide a principal with the adequate methodologies to improve the effort inputs of the agent when looking at the principal agent theory through an employer vs employee level of conduct.

Team production

editOn a related note, Drago and Garvey (1997) use Australian survey data to show that when agents are placed on individual pay-for-performance schemes, they are less likely to help their coworkers. This negative effect is particularly important in those jobs that involve strong elements of "team production" (Alchian and Demsetz 1972), where output reflects the contribution of many individuals, and individual contributions cannot be easily identified, and compensation is therefore based largely on the output of the team. In other words, pay-for-performance increases the incentives to free-ride, as there are large positive externalities to the efforts of an individual team member, and low returns to the individual (Holmström 1982, McLaughlin 1994).

The negative incentive effects implied are confirmed by some empirical studies, (e.g., Newhouse, 1973) for shared medical practices; costs rise and doctors work fewer hours as more revenue is shared. Leibowitz and Tollison (1980) find that larger law partnerships typically result in worse cost containment. As a counter, peer pressure can potentially solve the problem (Kandel and Lazear 1992), but this depends on peer monitoring being relatively costless to the individuals doing the monitoring/censuring in any particular instance (unless one brings in social considerations of norms and group identity and so on). Studies suggest that profit-sharing, for example, typically raises productivity by 3–5% (Jones and Kato 1995, Knez and Simester 2001), although there are some selection issues (Prendergast).

Empirical evidence

editThere is however considerable empirical evidence of a positive effect of compensation on performance (although the studies usually involve "simple" jobs where aggregate measures of performance are available, which is where piece rates should be most effective). In one study, Lazear (1996) saw productivity rising by 44% (and wages by 10%) in a change from salary to piece rates, with a half of the productivity gain due to worker selection effects. Research shows that pay for performance increases performance when the task at hand is more repetitive, and reduces performance when the task at hand requires more creative thinking.[18]

Furthermore,[19] formulated from their studies that compensation tend to have an impact on performance as a result of risk aversion and the level of work that a CEO is willing to input. This showed that when the CEO returned less effort then the data correlated a pay level of neutral aversion based on incentives. However, when offered incentives the data correlated a spike in performance as a direct result.

Conclusively, their studies indicated business owner (principal) and business employees (agents) must find a middle ground which coincides with an adequate shared profit for the company that is proportional to CEO pay and performance. In doing this risk aversion of employee efforts being low can be avoided pre-emptively.

- Paarsch and Shearer (1996) also find evidence supportive of incentive and productivity effects from piece rates, as do Banker, Lee, and Potter (1996), although the latter do not distinguish between incentive and worker selection effects.

- Rutherford, Springer and Yavas (2005) find evidence of agency problems in residential real estate by showing that real estate agents sell their own houses at a price premium of approximately 4.5% compared to their clients' houses.

- Fernie and Metcalf (1996) find that top British jockeys perform significantly better when offered percentage of prize money for winning races compared to being on fixed retainers.

- McMillan, Whalley and Zhu (1989) and Groves et al. (1994) look at Chinese agricultural and industrial data respectively and find significant incentive effects.

- Kahn and Sherer (1990)find that better evaluations of white-collar office workers were achieved by those employees who had a steeper relation between evaluations and pay.

- Nikkinen and Sahlström (2004) find empirical evidence that agency theory can be used, at least to some extent, to explain financial audit fees internationally.

- There is very little correlation between performance pay of CEOs and the success of the companies they manage.[20]

Contract design

editMilgrom and Roberts (1992) identify four principles of contract design: When perfect information is not available, Holmström (1979)[21] developed the Informativeness Principle to solve this problem. This essentially states that any measure of performance that (on the margin) reveals information about the effort level chosen by the agent should be included in the compensation contract. This includes, for example, Relative Performance Evaluation—measurement relative to other, similar agents, so as to filter out some common background noise factors, such as fluctuations in demand. By removing some exogenous sources of randomness in the agent's income, a greater proportion of the fluctuation in the agent's income falls under their control, increasing their ability to bear risk. If taken advantage of, by greater use of piece rates, this should improve incentives. (In terms of the simple linear model below, this means that increasing x produces an increase in b.)

However, setting incentives as intense as possible is not necessarily optimal from the point of view of the employer. The Incentive-Intensity Principle states that the optimal intensity of incentives depends on four factors: the incremental profits created by additional effort, the precision with which the desired activities are assessed, the agent's risk tolerance, and the agent's responsiveness to incentives. According to Prendergast (1999, 8), "the primary constraint on [performance-related pay] is that [its] provision imposes additional risk on workers ..." A typical result of the early principal–agent literature was that piece rates tend to 100% (of the compensation package) as the worker becomes more able to handle risk, as this ensures that workers fully internalize the consequences of their costly actions. In incentive terms, where we conceive of workers as self-interested rational individuals who provide costly effort (in the most general sense of the worker's input to the firm's production function), the more compensation varies with effort, the better the incentives for the worker to produce.

The third principle—the Monitoring Intensity Principle—is complementary to the second, in that situations in which the optimal intensity of incentives is high corresponds highly to situations in which the optimal level of monitoring is also high. Thus employers effectively choose from a "menu" of monitoring/incentive intensities. This is because monitoring is a costly means of reducing the variance of employee performance, which makes more difference to profits in the kinds of situations where it is also optimal to make incentives intense.

The fourth principle is the Equal Compensation Principle, which essentially states that activities equally valued by the employer should be equally valuable (in terms of compensation, including non-financial aspects such as pleasantness of the workplace) to the employee. This relates to the problem that employees may be engaged in several activities, and if some of these are not monitored or are monitored less heavily, these will be neglected, as activities with higher marginal returns to the employee are favoured. This can be thought of as a kind of "disintermediation"—targeting certain measurable variables may cause others to suffer. For example, teachers being rewarded by test scores of their students are likely to tend more towards teaching 'for the test', and de-emphasise less relevant but perhaps equally or more important aspects of education; while AT&T's practice at one time of paying programmers by the number of lines of code written resulted in programs that were longer than necessary—i.e., program efficiency suffering (Prendergast 1999, 21). Following Holmström and Milgrom (1990) and Baker (1992), this has become known as "multi-tasking" (where a subset of relevant tasks is rewarded, non-rewarded tasks suffer relative neglect). Because of this, the more difficult it is to completely specify and measure the variables on which reward is to be conditioned, the less likely that performance-related pay will be used: "in essence, complex jobs will typically not be evaluated through explicit contracts." (Prendergast 1999, 9).

Where explicit measures are used, they are more likely to be some kind of aggregate measure, for example, baseball and American Football players are rarely rewarded on the many specific measures available (e.g., number of home runs), but frequently receive bonuses for aggregate performance measures such as Most Valuable Player. The alternative to objective measures is subjective performance evaluation, typically by supervisors. However, there is here a similar effect to "multi-tasking", as workers shift effort from that subset of tasks which they consider useful and constructive, to that subset which they think gives the greatest appearance of being useful and constructive, and more generally to try to curry personal favour with supervisors. (One can interpret this as a destruction of organizational social capital—workers identifying with, and actively working for the benefit of, the firm – in favour of the creation of personal social capital—the individual-level social relations which enable workers to get ahead ("networking").)

Linear model

editThe four principles can be summarized in terms of the simplest (linear) model of incentive compensation:

where w (wage) is equal to a (the base salary) plus b (the intensity of incentives provided to the employee) times the sum of three terms: e (unobserved employee effort) plus x (unobserved exogenous effects on outcomes) plus the product of g (the weight given to observed exogenous effects on outcomes) and y (observed exogenous effects on outcomes). b is the slope of the relationship between compensation and outcomes.

The above discussion on explicit measures assumed that contracts would create the linear incentive structures summarised in the model above. But while the combination of normal errors and the absence of income effects yields linear contracts, many observed contracts are nonlinear. To some extent this is due to income effects as workers rise up a tournament/hierarchy: "Quite simply, it may take more money to induce effort from the rich than from the less well off." (Prendergast 1999, 50). Similarly, the threat of being fired creates a nonlinearity in wages earned versus performance. Moreover, many empirical studies illustrate inefficient behaviour arising from nonlinear objective performance measures, or measures over the course of a long period (e.g., a year), which create nonlinearities in time due to discounting behaviour. This inefficient behaviour arises because incentive structures are varying: for example, when a worker has already exceeded a quota or has no hope of reaching it, versus being close to reaching it—e.g., Healy (1985), Oyer (1997), Leventis (1997). Leventis shows that New York surgeons, penalised for exceeding a certain mortality rate, take less risky cases as they approach the threshold. Courty and Marshke (1997) provide evidence on incentive contracts offered to agencies, which receive bonuses on reaching a quota of graduated trainees within a year. This causes them to 'rush-graduate' trainees in order to make the quota.

Options framework

editIn certain cases agency problems may be analysed by applying the techniques developed for financial options, as applied via a real options framework.[22][23] Stockholders and bondholders have different objective—for instance, stockholders have an incentive to take riskier projects than bondholders do, and to pay more out in dividends than bondholders would like. At the same time, since equity may be seen as a call option on the value of the firm, an increase in the variance in the firm value, other things remaining equal, will lead to an increase in the value of equity, and stockholders may therefore take risky projects with negative net present values, which while making them better off, may make the bondholders worse off. Nagel and Purnanandam (2017) notice that since bank assets are risky debt claims, bank equity resembles a subordinated debt and therefore the stock's payoff is truncated by the difference between the face values of the corporation debt and of the bank deposits.[24] Based on this observation, Peleg-Lazar and Raviv (2017) show that in contrast to the classical agent theory of Michael C. Jensen and William Meckling, an increase in variance would not lead to an increase in the value of equity if the bank's debtor is solvent.[25]

Performance evaluation

editObjective

editThe major problem in measuring employee performance in cases where it is difficult to draw a straightforward connection between performance and profitability is the setting of a standard by which to judge the performance. One method of setting an absolute objective performance standard—rarely used because it is costly and only appropriate for simple repetitive tasks—is time-and-motion studies, which study in detail how fast it is possible to do a certain task. These have been used constructively in the past, particularly in manufacturing. More generally, however, even within the field of objective performance evaluation, some form of relative performance evaluation must be used. Typically this takes the form of comparing the performance of a worker to that of his peers in the firm or industry, perhaps taking account of different exogenous circumstances affecting that.

The reason that employees are often paid according to hours of work rather than by direct measurement of results is that it is often more efficient to use indirect systems of controlling the quantity and quality of effort, due to a variety of informational and other issues (e.g., turnover costs, which determine the optimal minimum length of relationship between firm and employee). This means that methods such as deferred compensation and structures such as tournaments are often more suitable to create the incentives for employees to contribute what they can to output over longer periods (years rather than hours). These represent "pay-for-performance" systems in a looser, more extended sense, as workers who consistently work harder and better are more likely to be promoted (and usually paid more), compared to the narrow definition of "pay-for-performance", such as piece rates. This discussion has been conducted almost entirely for self-interested rational individuals. In practice, however, the incentive mechanisms which successful firms use take account of the socio-cultural context they are embedded in (Fukuyama 1995, Granovetter 1985), in order not to destroy the social capital they might more constructively mobilise towards building an organic, social organization, with the attendant benefits from such things as "worker loyalty and pride (...) [which] can be critical to a firm's success ..." (Sappington 1991,63)

Subjective

editSubjective performance evaluation allows the use of a subtler, more balanced assessment of employee performance, and is typically used for more complex jobs where comprehensive objective measures are difficult to specify and/or measure. Whilst often the only feasible method, the attendant problems with subjective performance evaluation have resulted in a variety of incentive structures and supervisory schemes. One problem, for example, is that supervisors may under-report performance in order to save on wages, if they are in some way residual claimants, or perhaps rewarded on the basis of cost savings. This tendency is of course to some extent offset by the danger of retaliation and/or demotivation of the employee, if the supervisor is responsible for that employee's output.

Another problem relates to what is known as the "compression of ratings". Two related influences—centrality bias, and leniency bias—have been documented (Landy and Farr 1980, Murphy and Cleveland 1991). The former results from supervisors being reluctant to distinguish critically between workers (perhaps for fear of destroying team spirit), while the latter derives from supervisors being averse to offering poor ratings to subordinates, especially where these ratings are used to determine pay, not least because bad evaluations may be demotivating rather than motivating. However, these biases introduce noise into the relationship between pay and effort, reducing the incentive effect of performance-related pay. Milkovich and Wigdor (1991) suggest that this is the reason for the common separation of evaluations and pay, with evaluations primarily used to allocate training.

Finally, while the problem of compression of ratings originates on the supervisor-side, related effects occur when workers actively attempt to influence the appraisals supervisors give, either by influencing the performance information going to the supervisor: multitasking (focussing on the more visibly productive activities—Paul 1992), or by working "too hard" to signal worker quality or create a good impression (Holmström 1982); or by influencing the evaluation of it, e.g., by "currying influence" (Milgrom and Roberts 1988) or by outright bribery (Tirole 1992).

Incentive structures

editTournaments

editMuch of the discussion here has been in terms of individual pay-for-performance contracts; but many large firms use internal labour markets (Doeringer and Piore 1971, Rosen 1982) as a solution to some of the problems outlined. Here, there is "pay-for-performance" in a looser sense over a longer time period. There is little variation in pay within grades, and pay increases come with changes in job or job title (Gibbs and Hendricks 1996). The incentive effects of this structure are dealt with in what is known as "tournament theory" (Lazear and Rosen 1981, Green and Stokey (1983), see Rosen (1986) for multi-stage tournaments in hierarchies where it is explained why CEOs are paid many times more than other workers in the firm). See the superstar article for more information on the tournament theory.

Workers are motivated to supply effort by the wage increase they would earn if they win a promotion. Some of the extended tournament models predict that relatively weaker agents, be they competing in a sports tournaments (Becker and Huselid 1992, in NASCAR racing) or in the broiler chicken industry (Knoeber and Thurman 1994), would take risky actions instead of increasing their effort supply as a cheap way to improve the prospects of winning.

These actions are inefficient as they increase risk taking without increasing the average effort supplied. Neilson (2007) further added to this from his studies which indicated that when two employees competed to win in a tournament they have a higher chance of bending and or breaking the rules to win. Nelson (2007) also indicated that when the larger the price (incentive) the more inclined the agent (employee in this case) is to increase their effort parameter from Neilson's studies.[26]

A major problem with tournaments is that individuals are rewarded based on how well they do relative to others. Co-workers might become reluctant to help out others and might even sabotage others' effort instead of increasing their own effort (Lazear 1989, Rob and Zemsky 1997). This is supported empirically by Drago and Garvey (1997). Why then are tournaments so popular? Firstly, because—especially given compression rating problems—it is difficult to determine absolutely differences in worker performance. Tournaments merely require rank order evaluation.

Secondly, it reduces the danger of rent-seeking, because bonuses paid to favourite workers are tied to increased responsibilities in new jobs, and supervisors will suffer if they do not promote the most qualified person. This effectively takes the factors of ambiguity away from the principal agent problem by ensuring that the agent acts in the best interest of the principal but also ensures that the quality of work done is of an optimal level.

Thirdly, where prize structures are (relatively) fixed, it reduces the possibility of the firm reneging on paying wages. As Carmichael (1983) notes, a prize structure represents a degree of commitment, both to absolute and to relative wage levels. Lastly when the measurement of workers' productivity is difficult, e.g., say monitoring is costly, or when the tasks the workers have to perform for the job is varied in nature, making it hard to measure effort and/or performance, then running tournaments in a firm would encourage the workers to supply effort whereas workers would have shirked if there are no promotions.

Tournaments also promote risk seeking behavior. In essence, the compensation scheme becomes more like a call option on performance (which increases in value with increased volatility (cf. options pricing). Each of the players competing for the asymmetrically large top prize may benefit from reducing the expected value of their overall performance to the firm in order to increase their chance to have outstanding performance and win the prize. In moderation this can offset the greater risk aversion of agents vs principals because their social capital is concentrated in their employer while in the case of public companies the principal typically owns its stake as part of a diversified portfolio. Successful innovation is particularly dependent on employees' willingness to take risks. In cases with extreme incentive intensity, this sort of behavior can create catastrophic organizational failure. If the principal owns the firm as part of a diversified portfolio this may be a price worth paying for the greater chance of success through innovation elsewhere in the portfolio. If however the risks taken are systematic and cannot be diversified e.g., exposure to general housing prices, then such failures will damage the interests of principals and even the economy as a whole (cf. Kidder Peabody, Barings, Enron, AIG to name a few). Ongoing periodic catastrophic organizational failure is directly incentivized by tournament and other superstar/winner-take-all compensation systems (Holt 1995).

Deferred compensation

editTournaments represent one way of implementing the general principle of "deferred compensation", which is essentially an agreement between worker and firm to commit to each other. Under schemes of deferred compensation, workers are overpaid when old, at the cost of being underpaid when young. Salop and Salop (1976) argue that this derives from the need to attract workers more likely to stay at the firm for longer periods, since turnover is costly. Alternatively, delays in evaluating the performance of workers may lead to compensation being weighted to later periods, when better and poorer workers have to a greater extent been distinguished. (Workers may even prefer to have wages increasing over time, perhaps as a method of forced saving, or as an indicator of personal development. e.g., Loewenstein and Sicherman 1991, Frank and Hutchens 1993.) For example, Akerlof and Katz 1989: if older workers receive efficiency wages, younger workers may be prepared to work for less in order to receive those later. Overall, the evidence suggests the use of deferred compensation (e.g., Freeman and Medoff 1984, and Spilerman 1986—seniority provisions are often included in pay, promotion and retention decisions, irrespective of productivity.)

Energy consumption

editThe "principal–agent problem" has also been discussed in the context of energy consumption by Jaffe and Stavins in 1994. They were attempting to catalog market and non-market barriers to energy efficiency adoption. In efficiency terms, a market failure arises when a technology which is both cost-effective and saves energy is not implemented. Jaffe and Stavins describe the common case of the landlord-tenant problem with energy issues as a principal–agent problem. "[I]f the potential adopter is not the party that pays the energy bill, then good information in the hands of the potential adopter may not be sufficient for optimal diffusion; adoption will only occur if the adopter can recover the investment from the party that enjoys the energy savings. Thus, if it is difficult for the possessor of information to convey it credibly to the party that benefits from reduced energy use, a principal/agent problem arises."[27]

The energy efficiency use of the principal agent terminology is in fact distinct from the usual one in several ways. In landlord/tenant or more generally equipment-purchaser/energy-bill-payer situations, it is often difficult to describe who would be the principal and who the agent. Is the agent the landlord and the principal the tenant, because the landlord is "hired" by the tenant through the payment of rent? As Murtishaw and Sathaye, 2006 point out, "In the residential sector, the conceptual definition of principal and agent must be stretched beyond a strictly literal definition."

Another distinction is that the principal agent problem in energy efficiency does not require any information asymmetry: both the landlord and the tenant may be aware of the overall costs and benefits of energy-efficient investments, but as long as the landlord pays for the equipment and the tenant pays the energy bills, the investment in new, energy-efficient appliances will not be made. In this case, there is also little incentive for the tenant to make a capital efficiency investment with a usual payback time of several years, and which in the end will revert to the landlord as property. Since energy consumption is determined both by technology and by behavior, an opposite principal agent problem arises when the energy bills are paid by the landlord, leaving the tenant with no incentive to moderate her energy use. This is often the case for leased office space, for example.

The energy efficiency principal agent problem applies in many cases to rented buildings and apartments, but arises in other circumstances, most often involving relatively high up-front costs for energy-efficient technology. Though it is challenging to assess exactly, the principal agent problem is considered to be a major barrier to the diffusion of efficient technologies. This can be addressed in part by promoting shared-savings performance-based contracts, where both parties benefit from the efficiency savings. The issues of market barriers to energy efficiency, and the principal agent problem in particular, are receiving renewed attention because of the importance of global climate change and rising prices of the finite supply of fossil fuels.[28]

Trust relationships

editThe problem arises in client–attorney, probate executor, bankruptcy trustee, and other such relationships. In some rare cases, attorneys who were entrusted with estate accounts with sizeable balances acted against the interests of the person who hired them to act as their agent by embezzling the funds or "playing the market" with the client's money (with the goal of pocketing any proceeds).[citation needed]

This section can also be explored from the perspective of the trust game which captures the key elements of principal–agent problems. This game was first experimentally implemented by Berg, Dickhaut, and McCabe in 1995.[29] The setup of the game is that there are two players – trustor/principal (investor) and agents (investee). The trustor is endowed with a budget and can transfer some of the amounts to an agent in expectation of return over the transferred amount in the future. The trustee may send any part of the transferred amount back to the trustor. The amount transferred back by the trustee is referred to as trustworthiness. Most of the studies find that 45% of the endowment was transferred by the principal and around 33% transferred back by an agent. This means that investors are not selfish and can be trusted for economic transactions.

Trust within the principal-agent problem can also be seen from the perspective of an employer-employee relationship, whereby the employee (agent) has distrust in the employer (principal) which causes greater demotivation of the employee. It has been assumed that the principal having control in an organisational culture has benefits to for the organisation by creating greater productivity and efficiency. However it also entails some drawbacks that reduce the employee satisfaction such as reduced motivation, creativity, innovation and greater anxiety and stress.[30]

Personnel management

editWhen managing personnel in an organisational setting, the principal-agent problem surfaces when employees are hired to perform specific tasks and fulfil certain roles. In this environment, the goals of employee and employer may not be aligned. Often employees have the desire to further their own career or financial goals where employers often have the output interests of the organisation at the forefront of their actions and goals.[31]

Employees may reveal the principal-agent problem in their work by slacking off and not meeting targets or KPIs and Employers may reveal the principal-agent problem by implementing damaging policies or actions that make the working environment unsustainable.[31]

Bureaucracy and public administration

editIn the context of public administration, the principal–agent problem can be seen in such a way where public administration and bureaucrats are the agents and politicians and ministers are the principal authorities.[32] Ministers in the government usually command by framing policies and direct the bureaucrats to implement the public policies. However, there can be various principal-agent problems in the scenario such as misaligned intentions, information asymmetry, adverse selection, shirking, and slippage.

There are various situations where the ambitions and goals of the principals and agents may diverge. For example, politicians and the government may want public administration to implement a welfare policy program but the bureaucrats may have other interests as well such as rent-seeking. This results in a lack of implementation of public policies, hence the wastage of economic resources. This can also lead to the problem of shirking which is characterized as avoidance of performing a defined responsibility by the agent.

The information asymmetry problem occurs in a scenario where one of the two people has more or less information than the other. In the context of public administration, bureaucrats have an information advantage over the government and ministers as the former work at the ground level and have more knowledge about the dynamic and changing situation. Due to this government may frame policies that are not based on complete information and therefore problems in the implementation of public policies may occur. This can also lead to the problem of slippage which is defined as a myth where the principal sees that agents are working according to the pre-defined responsibilities but that might not be the reality.[33]

The problem of adverse selection is related to the selection of agents to fulfill particular responsibilities but they might deviate from doing so. The prime cause behind this is the incomplete information available at the desk of selecting authorities (principal) about the agents they selected.[34] For example, the Ministry of Road and Transport Highways hired a private company to complete one of its road projects, however, it was later found that the company assigned to complete road projects lacked technical know-how and had management issues.

The principal-agent problem in the public sector arises when there is a disconnect between politicians and public servants and their goals and interests. Other reasons that this occurs is because of political interference, bureaucratic resistance and public accountability.

Political interference happens when the politicians try and influence the decisions of public servants or bureaucrats to try and push their own interests which ultimately leads to policies being warped.[35]

Bureaucratic Resistance is when public servants are hesitant to implement the policies that have been proposed or agreed on, which ultimately causes policies to be implemented at a slow rate. Bureaucratic resistance may be due to lack of funding, resources or political support.[35]

Public accountability also plays a role in how the principal-agent theory impacts the public sector. When sworn in, politicians and public servants are responsible for ensure that they act in the interest of the public that they represent or work for, however, due to budget and resourcing issues as well as lack of transparency trust in the public sector often falls and a major disconnect grows.[35]

Economic theory

editIn economic theory, the principal-agent approach (also called agency theory) is part of the field contract theory.[36][37] In agency theory, it is typically assumed that complete contracts can be written, an assumption also made in mechanism design theory. Hence, there are no restrictions on the class of feasible contractual arrangements between principal and agent.

Agency theory can be subdivided in two categories: (1) In adverse selection models, the agent has private information about their type (say, their costs of exerting effort or their valuation of a good) before the contract is written. (2) In moral hazard models, the agent becomes privately informed after the contract is written. Hart and Holmström (1987) divide moral hazard models in the categories "hidden action" (e.g., the agent chooses an unobservable effort level) and "hidden information" (e.g., the agent learns their valuation of a good, which is modelled as a random draw by nature).[38] In hidden action models, there is a stochastic relationship between the unobservable effort and the verifiable outcome (say, the principal's revenue), because otherwise the unobservability of the effort would be meaningless. Typically, the principal makes a take-it-or-leave-it offer to the agent; i.e., the principal has all bargaining power. In principal–agent models, the agent often gets a strictly positive rent (i.e. their payoff is larger than their reservation utility, which they would get if no contract were written), which means that the principal faces agency costs. For example, in adverse selection models the agent gets an information rent, while in hidden action models with a wealth-constrained agent the principal must leave a limited-liability rent to the agent.[36] In order to reduce the agency costs, the principal typically induces a second-best solution that differs from the socially optimal first-best solution (which would be attained if there were complete information). If the agent had all bargaining power, the first-best solution would be achieved in adverse selection models with one-sided private information as well as in hidden action models where the agent is wealth-constrained.

Contract-theoretic principal–agent models have been applied in various fields, including financial contracting,[39] regulation,[40] public procurement,[41] monopolistic price-discrimination,[42] job design,[43] internal labor markets,[44] team production,[45] and many others. From the cybernetics point of view, the Cultural Agency Theory arose in order to better understand the socio-cultural nature of organisations and their behaviours.

Negotiation

editIn the negotiation problem, the principal commissions an agent to conduct negotiations on its behalf. The principal may delegate certain authority to the agent, including the ability to conclude negotiations and enter into binding contracts. The principal may consider and assign a utility to each issue in the negotiation.[46] However, it is not always the case that the principal will explicitly inform the agent of what it considers to be the minimally acceptable terms, otherwise known as the reservation price.[47] The successfulness of a negotiation will be determined by a range of factors. These include: the negotiation objective, the role of the negotiating parties, the nature of the relationship between the negotiating parties, the negotiating power of each party and the negotiation type. Where there are information asymmetries between the principal and agent, this can affect the outcome of the negotiation. As it is impossible for a manager to attend all upcoming negotiations of the company, it is common practice to assign internal or external negotiators to represent the negotiating company at the negotiation table. With the principal–agent problem, two areas of negotiation emerge:

- negotiations between the agent and the actual negotiating partner (negotiations at the table)

- internal negotiations, as between the agent and the principal (negotiations behind the table).[48]

The principal-agent problem can arises in representative negotiations where the interests of the principal and the agent are misaligned. The principal cannot directly observe the agent's efforts during the course of the negotiation. In such circumstances, this may lead to the agent employing negotiation tactics which are unfavourable to the principal, but which benefit the agent. Depending upon how the agent's reward is determined, the principal may be able to effectively retain control over the agent. If the agent receives a fixed fee, the agent may nonetheless act in a manner that is inconsistent with the principal's interests. The agent may adopt this strategy if they believe the negotiation is a one-shot game. The agent may adopt a different strategy if they account for reputational consequences of acting against the principal's interests. Similarly, if the negotiation is a repeated game, and the principal is aware of the results of the first iteration, the agent may opt to employ a different strategy which more closely aligns with the interests of the principal in order to ensure the principal will continue to contract with the agent in the following iterations. If the agent's reward is dependent upon the outcome of the negotiation, then this may help align the differing interests.[49]

In popular culture

edit- The Mamas & the Papas 1967 song Creeque Alley refers to the principal–agent problem in the lyric, "Broke, busted, disgusted; agents can't be trusted."

See also

edit- Iron law of oligarchy

- Managerial state

- Professional–managerial class

- Adverse selection

- Alignment problem

- Autonomous agency theory

- Bayesian persuasion - a special case of a principal-agent setting.

- Contract theory

- Control fraud

- Cost overrun

- Fiduciary

- Honest services fraud

- Multiple principal problem

- Participative decision-making

- Self-dealing

- Structure and agency

- The Market for Lemons

- Trustee

- Skin in the game (phrase)

References

edit- ^ Eisenhardt, K.M. (1989), "Agency Theory: An Assessment and Review", The Academy of Management Review, 14 (1): 57–74, doi:10.5465/amr.1989.4279003, JSTOR 258191.

- ^ Adams, Julia (1996). "Principals and Agents, Colonialists and Company Men: The Decay of Colonial Control in the Dutch East Indies". American Sociological Review. 61 (1): 12–28. doi:10.2307/2096404. ISSN 0003-1224. JSTOR 2096404. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ^ Pay Without Performance, Lucian Bebchuk and Jesse Fried, Harvard University Press 2004 (preface and introduction Archived February 14, 2019, at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ "Agency Costs". Investopedia. Archived from the original on April 22, 2019. Retrieved July 3, 2012.

- ^ Gailmard, Sean (2014), "Accountability and Principal–Agent Theory", The Oxford Handbook of Public Accountability, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199641253.013.0016, ISBN 978-0-19-964125-3

- ^ a b Voorn, B.; Van Genugten, M.; Van Thiel, S. (2019). "Multiple principals, multiple problems: Implications for effective governance and a research agenda for joint service delivery". Public Administration. 97 (3): 671–685. doi:10.1111/padm.12587. hdl:2066/207394.

- ^ Downes, Alexander B. (2021). Catastrophic success : why foreign-imposed regime change goes wrong. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-6116-4. OCLC 1252920900.

- ^ Bernheim, B.D.; Whinston, M.D. (1986). "Common agency". Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society. 54 (4): 923. doi:10.2307/1912844. JSTOR 1912844.

- ^ Martimort, D. (1996). "The multiprincipal nature of government". European Economic Review. 40 (3–5): 673–85. doi:10.1016/0014-2921(95)00079-8.

- ^ Moe, T.M. (2005). "Power and political institutions". Perspectives on Politics. 3 (2). doi:10.1017/S1537592705050176 (inactive December 9, 2024). S2CID 39072417.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of December 2024 (link) - ^ Potucek, M (2017). Public Policy: A Comprehensive Introduction. Prague, Charles University: Karolinum Press.

- ^ Mitnick, Barry M. (January 2006). "Origin of the Theory of Agency". Archived from the original on March 7, 2021. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ Jensen, Michael C.; Meckling, William H. (October 1976). "Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure" (PDF). Journal of Financial Economics. 3 (4): 305–360. doi:10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- ^ Pendergast, Canice (1999). "The Provision of Incentives in Firms". Journal of Economic Literature. 37 (1): 7–63. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.558.6657. doi:10.1257/jel.37.1.7. JSTOR 2564725.

- ^ Paula Szuchman, Jenny Anderson. It's Not You, It's the Dishes (originally published as Spousonomics): How to Minimize Conflict and Maximize Happiness in Your Relationship. Random House Digital, Inc., June 12, 2012. Page 210. Accessed on May 31, 2013

- ^ "Only the tip, but size is important". The Age. December 11, 2004. Archived from the original on April 1, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- ^ Crifo, Patricia. "INCENTIVES IN AGENCY RELATIONSHIPS: TO BE MONETARY OR NON-MONETARY?" (PDF). Retrieved October 29, 2020.[dead link]

- ^ Pink, Daniel H. (2009). Drive: The Surprising Truth about What Motivates Us. New York: Riverhead Books. ISBN 9781594488849.

- ^ Haubrich, Joseph (1994). "Risk Aversion, Performance Pay, and the Principal-Agent Problem". Journal of Political Economy. 102 (2): 258–276. doi:10.1086/261931. S2CID 15450754. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- ^ Jensen, M. C.; Murphy, K. J. (1990). "Performance Pay and Top-Management Incentives". Journal of Political Economy. 98 (2): 225–264. doi:10.1086/261677. JSTOR 2937665.

- ^ "Moral Hazard and Observability" Archived April 27, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, The Bell Journal of Economics, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Spring, 1979), pp. 74-91

- ^ Aswath Damodaran: Applications Of Option Pricing Theory To Equity Valuation Archived April 27, 2012, at the Wayback Machine and Option Pricing Applications in Valuation Archived September 16, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ D. Mauer and S. Sarkar (2001). Real Options, Agency Conflicts, and Financial Policy Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine; G. Siller-Pagaza, G. Otalora, E. Cobas-Flores (2006). The Impact of Real Options in Agency Problems Archived June 2, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [S. Nagel and A. Purnanandam (2017). Bank Risk Dynamics and Distance to Default Archived April 23, 2023, at the Wayback Machine;

- ^ [S. Peleg-Lazar and A. Raviv (2017). Bank Risk Dynamics Where Assets are Risky Debt Claims Archived August 5, 2017, at the Wayback Machine;

- ^ Nielson, Williams. Personal Economics (3 ed.). TENNESSEE, KNOXVILLE: Pearson Education. pp. 107–118.

- ^ Jaffe, Adam B; Stavins, Robert N (1994). "The energy efficiency gap: What does it mean?" (PDF). Energy Policy. 22 (10): 805. doi:10.1016/0301-4215(94)90138-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 1, 2019. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- ^ "Mind the Gap". IEA. Archived from the original on May 1, 2019. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- ^ Berg, J., Dickhaut, J., & McCabe, K. (1995). "Trust, Reciprocity, and Social History". Games and Economic Behavior, 10(1), 122–142. doi:10.1006/game.1995.1027

- ^ Falk, Armin; Kosfeld, Michael (December 2006). "The Hidden Costs of Control". American Economic Review. 96 (5): 1611–1630. doi:10.1257/aer.96.5.1611. ISSN 0002-8282. Archived from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved March 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Baker, Rose M. (2019). "The Agency of the Principal–Agent Relationship: An Opportunity for HRD". Advances in Developing Human Resources. 21 (3): 303–318. doi:10.1177/1523422319851274. S2CID 197688734.

- ^ Potucek, M. (2017). Public Policy: A Comprehensive Introduction. Prague: Karolinum Press, Charles University

- ^ Lane, J. E., & Kivistö, J. (2008). "Interests, Information, and Incentives in Higher Education: Principal–Agent Theory and Its Potential Applications to the Study of Higher Education Governance". Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research.

- ^ Garba, et al. (2020). "Government Higher Education Institutions Relationship Vide the Lens of the Principal–Agent Theory". The 27th International Business Information Management Association Conference (pp. 1–11). Milan: International Business Information Management Association.

- ^ a b c Wood, B. Dan (October 14, 2010). Agency Theory and the Bureaucracy. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199238958.003.0008.

- ^ a b Laffont, Jean-Jacques; Martimort, David (2002). The theory of incentives: The principal-agent model. Princeton University Press.

- ^ Bolton, Patrick; Dewatripont, Matthias (2005). Contract theory. MIT Press.

- ^ Hart, Oliver; Holmström, Bengt (1987). "The theory of contracts". In Bewley, T. (ed.). Advances in Economics and Econometrics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 71–155.

- ^ Tirole, Jean (2006). The theory of corporate finance. Princeton University Press.

- ^ Baron, David P.; Myerson, Roger B. (1982). "Regulating a Monopolist with Unknown Costs". Econometrica. 50 (4): 911–930. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.407.6185. doi:10.2307/1912769. JSTOR 1912769.

- ^ Schmitz, Patrick W. (2013). "Public procurement in times of crisis: The bundling decision reconsidered". Economics Letters. 121 (3): 533–536. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2013.10.015.

- ^ Maskin, Eric; Riley, John (1984). "Monopoly with Incomplete Information". RAND Journal of Economics. 15 (2): 171–196. JSTOR 2555674.

- ^ Schmitz, Patrick W. (2013). "Job design with conflicting tasks reconsidered". European Economic Review. 57: 108–117. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2012.11.001.

- ^ Kräkel, Matthias; Schöttner, Anja (2012). "Internal labor markets and worker rents". Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 84 (2): 491–509. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.320.692. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2012.08.008.

- ^ Homström, Bengt (1982). "Moral hazard in teams". Bell Journal of Economics. 13 (2): 324–340. doi:10.2307/3003457. JSTOR 3003457.

- ^ Piasecki, Krzysztof; Roszkowska, Ewa; Wachowicz, Tomasz; Filipowicz-Chomko, Marzena; Łyczkowska-Hanćkowiak, Anna (July 29, 2021). "Fuzzy Representation of Principal's Preferences in Inspire Negotiation Support System". Entropy. 23 (8): 981. Bibcode:2021Entrp..23..981P. doi:10.3390/e23080981. ISSN 1099-4300. PMC 8392366. PMID 34441121.

- ^ Lax, David A.; Sebenius, James K. (September 1991). "Negotiating Through an Agent". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 35 (3): 474–493. doi:10.1177/0022002791035003004. ISSN 0022-0027. S2CID 143173392. Archived from the original on May 2, 2022. Retrieved May 2, 2022.

- ^ Jung, Stefanie; Krebs Peter (15 June 2019). "The Essentials of Contract Negotiation". Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-12866-1 Archived May 2, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Miller, Gary J.; Whitford, Andrew B. (April 1, 2002). "Trust and Incentives in Principal-Agent Negotiations: The 'Insurance/Incentive Trade-Off'". Journal of Theoretical Politics. 14 (2): 231–267. doi:10.1177/095169280201400204. ISSN 0951-6298. S2CID 17436198. Archived from the original on January 20, 2023. Retrieved May 2, 2022.

Further reading

edit- Azfar, Omar (2007). "Chapter 8: Disrupting Corruption" (PDF). In Shah, Anwar (ed.). Performance Accountability and Combating Corruption. World Bank. doi:10.1596/978-0-8213-6941-8. hdl:10986/6732. ISBN 9780821369418.

- Eisenhardt, K. (1989). "Agency theory: An assessment and review". Academy of Management Review. 14 (1): 57–74. doi:10.5465/amr.1989.4279003. JSTOR 258191.

- Fleckinger, Pierre, David Martimort, and Nicolas Roux. 2024. "Should They Compete or Should They Cooperate? The View of Agency Theory." Journal of Economic Literature, 62 (4): 1589–1646.

- Gailmard, Sean (2014), "Accountability and Principal–Agent Theory" in The Oxford Handbook of Public Accountability. Oxford University Press.

- Green, J. R.; Stokey, N. L. (1983). "A Comparison of Tournaments and Contracts". Journal of Political Economy. 91 (3): 349–64. doi:10.1086/261153. JSTOR 1837093. S2CID 18043549.

- Mind the Gap—Quantifying Principal–Agent Problems in Energy Efficiency (PDF), IEA, 2007, archived from the original (PDF) on September 30, 2018, retrieved February 7, 2013.

- Laffont, Jean-Jacques and Martimort, David (2002). The Theory of Incentives: The Principal–Agent Model. Princeton University Press.

- Miller, Gary. 2005. “The Political Evolution of Principal-Agent Models” Annual Review of Political Science 8: 203–25..

- Nikkinen, Jussi; Sahlström, Petri (2004). "Does agency theory provide a general framework for audit pricing?". International Journal of Auditing. 8 (3): 253–262. doi:10.1111/j.1099-1123.2004.00094.x.

- Rees, R., 1985. "The Theory of Principal and Agent—Part I". Bulletin of Economic Research, 37(1), 3–26

- Rees, R., 1985. "The Theory of Principal and Agent—Part II". Bulletin of Economic Research, 37(2), 75–97

- Rutherford, R. & Springer, T. & Yavas, A. (2005). Conflicts between Principals and Agents: Evidence from Residential Brokerage. Journal of Financial Economics (76), 627–65.

- Rosen, S. (1986). "Prizes and Incentives in Elimination Tournaments". American Economic Review. 76 (4): 701–715. JSTOR 1806068.

- Sappington, David E. M. (1991). "Incentives in Principal–Agent Relationships". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 5 (2): 45–66. doi:10.1257/jep.5.2.45. JSTOR 1942685.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (1987). "Principal and agent", The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 3, pp. 966–71.

External links

edit- Quotations related to Principal–agent problem at Wikiquote