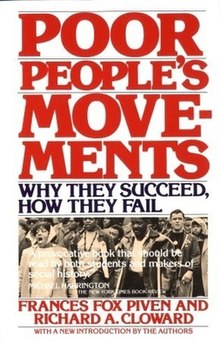

Poor People's Movements

Poor People's Movements: Why They Succeed, How They Fail (1977; second edition 1979) is a book about social movements by the American academics and political activists Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward. The book advanced Piven and Cloward's theories about the possibilities and limits of social change through protest. The book uses four case studies: the Unemployed Workers' Movement of the Great Depression, the Industrial Workers' Movement, the Civil Rights Movement, and the Welfare Rights Movement, particularly the activity of the National Welfare Rights Organization.[1][2][3]

| |

| Author | Frances Fox Piven and Richard A. Cloward |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Subject | Social Movements |

| Publisher | Pantheon Books, Random House (second edition) |

Publication date | 1977 (2nd Edition: 1979) |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover and Paperback) |

| Pages | 382 |

| ISBN | 0-394-72697-9 |

The book evoked strong reactions at the time of its publication, with founder of the Democratic Socialists of America Michael Harrington calling it "a provocative book that should be read by both students and makers of social history."[4] Following its publication, it was frequently assigned in American university courses. [5][6]

It has had an enduring effect on academic understandings of political movements led by the poor, leading to such spinoffs as "Rich People's Movements."[7] The book was described as a "classic" by Jannie Jackson in 2019 and Daniel Devir in 2020, as "seminal" by Sam Adler-Bell, and as "the progressive bible" by Ed Pilkington.[8][9][10] [11]

Synopsis

editThe book argues that organizing the poor to form long-term political pressure groups is futile and distracts from winning larger gains in moments of opportunity opened by mass protest: "...that by endeavoring to do what they cannot do, organizers fail to do what they can do...all too often, when workers erupted in strikes, organizers collected dues cards; when tenants refused to pay rent and stood off marshals, organizers formed building committees; when people were burning and looting, organizers used that 'moment of madness' to draft constitutions."[12]

People generally acquiesce to material inequality. Only in moments of crisis do people question the arrangement of society. Massive, rapid economic change creates these crises. Piven and Cloward identify three signals indicating the possibility of mass protest: first, that the harm and indignity falling upon people is a fault of the system and not due to individual failing; second, when ordinarily fatalistic people begin to demand rights or other forms of change; and third, when people who ordinarily consider themselves helpless begin to see themselves as capable of changing their conditions.[13]

Protest by the poor faces greater constraints than other groups. Welfare recipients cannot easily go to Congress or state legislatures en masse, and when they do, they are easily ignored, whereas at the welfare offices they are difficult to ignore and can meaningfully disrupt operations.[14] Context also constrains the possible targets of protests, "[t]enants experience the leaking ceilings and cold radiators, and they recognize the landlord. They do not recognize the banking, real estate, and construction systems....when the poor rebel they so often rebel against the overseer of the poor, or the slumlord, or the middling merchant, and not against the banks or the governing elites to whom the overseer, the slumlord, and the merchant also defer."[15] The authors argue that "people cannot defy institutions to which they have no access, and to which they make no contribution."[16]

Cloward and Piven examine the Unemployed Workers' Movement, Industrial Workers' Movement, the Civil Rights Movement, and the Welfare Rights Movement. They find that in each movement, activists and organizers concentrated on building formally structured mass-membership organizations of poor and working-class people, with the hope that these organizations would win concessions from elites that would allow the organizations to grow or at least maintain membership. Attempts to grow these mass-membership opposition groups inevitably lead to conciliation with elites to support such groups and attempts by organizers to rein in the disruptive potential of mass movements.[17]

The authors explore the welfare rights movement's fight to increase welfare eligibility. They give Edward Sparer as an example of a welfare rights lawyer working in this area who challenged "[m]an-in-the-house rules, residence laws, employable mother rules, and a host of other statutes, policies, and regulations which kept people off the roles were eventually struck down."[18]

Reception

editIn a review for The Nation, Jack Beatty said the book was "bound to have a wide and various influence" and called it "disturbing". While praising the analysis of the industrial workers' movement, Beatty criticized the Piven-Cloward plan for backfiring, noting that in the urban politics of the late 1960s, one "could not talk to a cabdriver or a counterman, a waitress or a barber without hearing a bitter diatribe against the welfare poor". Beatty argued that the backlash to increased use of the welfare system led to working class support for Republican candidates like Richard Nixon.[19] The book also attracted detractors from the right, who accused the authors of "blunt extremism".[20]

Influence

editPoor People's Movements and the associated Cloward-Piven Strategy were criticized following publication and remain a contentious position among activists and organizers.[21] The arguments made in the book have continued to interest scholars, activists, and organizers, with one scholar commenting that "after 25 years, PPM continues to be read, discussed, and taught, warts and all."[22][23]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward. Poor People's Movements: Why They Succeed, How They Fail. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Vintage Books (Random House), 1979.

- ^ "The Problem With Community Land Trusts". jacobinmag.com. Retrieved 2021-11-27.

- ^ "Philly's Housing Encampments of 2020 Led to a Nationally Celebrated Deal. Then It All Began to Unravel". Philadelphia Magazine. 2021-10-10. Retrieved 2021-11-27.

- ^ Harrington, Michael (11 December 1977). "Disturbance From Below". The New York Times. ProQuest 123263063.

[Poor People's Movements] is a provocative book that should be read by both students and makers of social history.

- ^

Traub, Alex (10 May 2019). "This 86-Year-Old Radical May Save (or Sink) the Democrats". New York Times. New York. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

Following the crucible of the '60s and early '70s, Ms. Piven's academic career flourished. Her books, particularly "Poor People's Movements," were assigned in college classes.

- ^

Kerbo, Harold (1 January 1979). "Poor People's Movements: Why They Succeed, How They Fail. By Frances Fox Piven and Richard A. Cloward. New York: Pantheon Books, 1977". Western Sociological Review. 10: 108–110. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

No doubt like many others, I will be offering the book as a required reading in future classes.

- ^

Martin, Isaac (2 September 2013). Rich People's Movements: Grassroots Campaigns to Untax the One Percent. Oxford University Press. pp. xi–xii. ISBN 978-0199389995.

The title of the book is intended to pay homage to the classic study of Poor People's Movements by the sociologists Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward. . . . Their book remains a classic work of social science, and many of its arguments have withstood decades of criticism by other sociologists and political scientists.

- ^ "'Poverty Is Not Just a Measure of How Much Cabbage and Potatoes You Need to Live On'". FAIR. 2019-10-01. Retrieved 2021-11-27.

- ^ Denvir, Daniel (January 2020). "What a Bernie Sanders Presidency Would Look Like". In These Times. Chicago: Institute for Public Affairs. Retrieved 2021-11-27.

- ^ Adler-Bell, Sam (Winter 2021). "Organizing the Unemployed". Dissent. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

- ^ Pilkington, Ed (November 24, 2022), "Interview: 'The US can still become a fascist country': Frances Fox Piven's midterms postmortem", The Guardian, London

- ^ Poor People's Movements (1979) page xxi-xxii.

- ^ Poor People's Movements (1979) page 4.

- ^ Poor People's Movements (1979) page 22.

- ^ Poor People's Movements (1979) page 20.

- ^ Poor People's Movements (1979) page 23.

- ^ Poor People's Movements (1979) page xx.

- ^ Poor People's Movements, page 272.

- ^ Beatty, Jack (October 8, 1977). "The Language of the Unheard". The Nation. New York: Nation Company, L.P.

- ^ Kurtz, Stanley (14 February 2011). "Frances Fox Piven Speaks". National Review. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

Actually, [Fox Piven] is disguising the blunt extremism of her writings.

- ^ Hufnagel, Ashley (2021). "Rearticulating a New Poor People's Campaign: Fifty Years of Grassroots Anti-Poverty Movement Organizing". Feminist Formations. 33 (1): 189–220. doi:10.1353/ff.2021.0009. S2CID 236644826.

- ^ Kling, Joseph (2003). "Poor People's Movements 25 Years Later: Historical Context, Contemporary Issues". Perspectives on Politics. 1 (4): 727–32. doi:10.1017/S1537592703000525. S2CID 145802932.

- ^ Lefkowitz, Joel (2003). "The Success of Poor People's Movements: Empirical Tests and the More Elaborate Model". Perspectives on Politics. 1 (4): 721–726. doi:10.1017/S1537592703000513. S2CID 145448348.