The yellow-billed magpie (Pica nuttalli), also known as the California magpie, is a large corvid that inhabits California's Central Valley and the adjacent chaparral foothills and mountains. Apart from its having a yellow bill and a yellow streak around the eye, it is virtually identical to the black-billed magpie (Pica hudsonia) found in much of the rest of North America. The scientific name commemorates the English naturalist Thomas Nuttall.

| Yellow-billed magpie Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Turlock, California | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Corvidae |

| Genus: | Pica |

| Species: | P. nuttalli

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pica nuttalli (Audubon, 1837)

| |

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Taxonomy

editmtDNA sequence analysis[3] indicates a close relationship between the yellow-billed magpie and the black-billed magpie, rather than between the outwardly very similar black-billed and European magpies (P. pica).

The Korean subspecies of the European magpie (P. p. sericea) is more distantly related to all other (including North American) forms judging from the molecular evidence, and thus, either the North American forms are maintained as specifically distinct. The Korean (and possibly related) subspecies are also elevated to species status, or all magpies are considered to be subspecies of a single species, Pica pica.

Combining fossil evidence[4] and paleobiogeographical considerations with the molecular data indicates that the yellow-billed magpie's ancestors became isolated in California quite soon after the ancestral magpies colonized North America due to early ice ages and the ongoing uplift of the Sierra Nevada, but that during interglacials there occurred some gene flow between the yellow- and black-billed magpies until reproductive isolation was fully achieved in the Pleistocene.

The yellow-billed magpie is adapted to the hot summers of California's Central Valley and experiences less heat stress than the black-billed magpie.[5]

Behaviour

editThe yellow-billed magpie is gregarious and roosts communally.[6] There may be a cluster of communal roosts in one general area made up of a central roost containing many birds and several outlying roosts with fewer.[6]

Yellow-billed magpie flocks are known to engage in funeral-like behavior for their dead. When a magpie dies, a gathering of them congregates around the deceased bird where they call out loudly for 10–15 minutes.[7]

Breeding

editThe yellow-billed magpie prefers groves of tall trees along rivers and near open areas, though in some cities they have begun to nest in vacant lots and other weedy places. A pair of birds build a dome-shaped nest with sticks and mud on a high branch.[8] Nests maybe 14 meters above the ground and are sometimes built far out on long branches to prevent predators from reaching them.[5] They nest in small colonies, or occasionally alone.[8] Even when nesting close to other birds they may exhibit some territorial behavior.[5] These birds are permanent residents and do not usually wander far outside of their breeding range.[5]

Extra-pair copulation is not uncommon among yellow-billed magpies. After mating, a male will exhibit mate-guarding, preventing the female from mating with other males until she lays the first egg.[9] The clutch contains 5 to 7 eggs which are incubated by the female for 16 to 18 days.[5] Both parents feed the nestlings a diet of mostly insects until fledging occurs in 30 days.[5]

Food and feeding

editThese omnivorous birds forage on the ground, mainly eating insects, especially grasshoppers, but also carrion, acorns and fruit in fall and winter.[10] They are attracted to recently butchered carcasses on farms and ranches. They pick through garbage at landfills and dumping sites, and sometimes hunt rodents.[5]

Diseases

editThis bird is extremely susceptible to West Nile virus. Between 2004 and 2006 it is estimated that 50% of all yellow-billed magpies died of the virus.[11] Because the bird tends to roost near water bodies such as rivers, it is often exposed to mosquitoes.[6]

Avian poxvirus is another contagious viral infection that Yellow-billed magpies face that have raised concerns for their population. It has been documented in some individuals, leading to the development of skin lesions, nodules, and sometimes death. While the prevalence of avian poxvirus in Yellow-billed magpies varies, it is considered a potential concern for the species.

The birds are also at risk of lead poisoning, primarily due to the ingestion of spent lead ammunition fragments found in carrion or discarded game animals. Lead poisoning has been a significant issue for scavenging birds, and efforts to reduce the use of lead ammunition in hunting areas adjacent to Yellow-billed magpie habitats are being undertaken to mitigate this threat.

Conservation

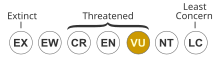

editThe IUCN classifies the bird as a vulnerable species.[1] The Nature Conservancy places it in the vulnerable category.[2] Besides West Nile Virus, threats include loss of habitat and rodent poison.[5] The bird has a limited area of distribution but is widespread throughout the area and still common in many places.[5]

Habitat Loss is the ongoing urbanization and agricultural development in California's Central Valley have led to the destruction and fragmentation of the Yellow-billed magpie's preferred nesting and foraging habitats. As groves of tall trees are cleared for development, the available breeding sites for these birds are diminishing.

Rodent Poison also is the use of rodenticides and pesticides in agricultural and urban areas poses a direct threat to the Yellow-billed magpie population. These chemicals can contaminate the bird's food sources and have detrimental effects on their health.

Climate Change and its associated impacts, such as increased temperatures and altered precipitation patterns, may affect the availability of the bird's food sources and nesting sites. Prolonged droughts and extreme weather events can further stress their populations.

Conservation Efforts where several organizations, including The Nature Conservancy and local conservation groups, are actively engaged in efforts to protect and preserve the Yellow-billed magpie. These efforts include habitat restoration, monitoring of populations, and education campaigns to raise awareness about the importance of safeguarding this species.

References

edit- ^ a b c BirdLife International. 2018. Pica nuttalli. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T22705874A94039098. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-3.RLTS.T22705874A94039098.en. Accessed 15 December 2018.

- ^ a b "NatureServe Explorer 2.0". explorer.natureserve.org. Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- ^ Lee, Sang-im; Parr, Cynthia S.; Hwang, Youna; Mindell, David P. & Choea, Jae C. (2003). "Phylogeny of magpies (genus Pica) inferred from mtDNA data" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 29 (2): 250–257. doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00096-4. PMID 13678680.

- ^ Miller, Alden H. & Bowman, Robert I. (1956). "A Fossil Magpie from the Pleistocene of Texas" (PDF). Condor. 58 (2): 164–165. doi:10.2307/1364980. JSTOR 1364980.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Yellow-billed Magpie Species Account. Yolo Conservation Plan.

- ^ a b c Protocol for censusing Yellow-billed Magpies at communal roosts. PRBO Conservation.

- ^ "Black-billed Magpie Life History, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved 2020-02-09.

- ^ a b Protocol for monitoring Yellow-billed Magpie nests. PRBO Conservation.

- ^ Birkhead, T.R.; Clarkson, K.; Reynolds, M.D.; Koenig, W.D. (1992). "Copulation and mate guarding in the Yellow-Billed Magpie Pica nuttalli and a comparison with the Black-Billed Magpie P. pica". Behaviour. 121 (1–2): 110–30. doi:10.1163/156853992X00462. JSTOR 4535022.

- ^ "Yellow-billed Magpie". Audubon. Retrieved 2024-04-22.

- ^ Veterinary Geneticists Already on the Side of Audubon's Bird of the Year. UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine. December 10, 2009