Pentecost (also called Whit Sunday, Whitsunday or Whitsun) is a Christian holiday which takes place on the 49th day (50th day when inclusive counting is used) after Easter Day.[1] It commemorates the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Apostles of Jesus while they were in Jerusalem celebrating the Feast of Weeks, as described in the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 2:1–31).[2] The Catholic Church believes the Holy Spirit descended upon Mary, the mother of Jesus, at the same time, as recorded in the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 1:14).[3]

| Pentecost | |

|---|---|

| |

| Also called |

|

| Observed by | Catholic Church, Old Catholics, Lutherans, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Amish, Anglicans and other Christians |

| Type | Christian |

| Significance | Celebrates the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Apostles and other followers of Jesus; birth of the Church |

| Celebrations | Church services, festive meals, processions, baptism, confirmation, ordination, folk customs, dancing, spring and woodland rites. |

| Observances | Prayer, vigils, fasting (pre-festival), novenas, retreats, Holy Communion, litany |

| Date | 50 days after Easter |

| 2024 date |

|

| 2025 date |

|

| 2026 date |

|

| 2027 date |

|

| Related to | Jesus Day, Shavuot, Rosalia, Green Week, Pinkster, Whit Monday, Whit Tuesday, Whit Friday, Trinity Sunday |

Pentecost is one of the Great feasts in the Eastern Orthodox Church, a Solemnity in the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church, a Festival in the Lutheran Churches, and a Principal Feast in the Anglican Communion. Many Christian denominations provide a special liturgy for this holy celebration. Since its date depends on the date of Easter, Pentecost is a "moveable feast". The Monday after Pentecost is a legal holiday in many European, African and Caribbean countries.

Etymology

editThe term Pentecost comes from Koinē Greek: πεντηκοστή, romanized: pentēkostē, lit. 'fiftieth'. One of the meanings of "Pentecost" in the Septuagint, the Koine translation of the Hebrew Bible, refers to the festival of Shavuot, one of the Three Pilgrimage Festivals, which is celebrated on the fiftieth day after Passover according to Deuteronomy 16:10,[i] and Exodus 34:22,[4] where it is referred to as the "Festival of Weeks" (Koinē Greek: ἑορτὴν ἑβδομάδων, romanized: heortēn hebdomádōn).[5][6][7] The Septuagint uses the term Pentēkostē in this context in the Book of Tobit and 2 Maccabees.[clarification needed][8][9][10]

The translators of the Septuagint also used the word in two other senses: to signify the year of Jubilee (Leviticus 25:10)[11][8] an event which occurs every 50th year, and in several passages of chronology as an ordinal number.[ii] The term has also been used in the literature of Hellenistic Judaism by Philo of Alexandria and Josephus to refer to Shavuot.[7]

Background

editIn Judaism, Shavuot is a harvest festival that is celebrated seven weeks and one day after the first day of Passover in Deuteronomy 16:9, or seven weeks and one day after the Sabbath according to Leviticus 23:16.[18][19][20] It is discussed in the Mishnah and the Babylonian Talmud, tractate Arakhin.[21] The actual mention of fifty days comes from Leviticus 23:16.[5][22]

The Festival of Weeks is also known as the Feast of Harvest in Exodus 23:16 and the Day of First Fruits in Numbers 28:26.[19] In Exodus 34:22, it is called the "first fruits of the wheat harvest."[20]

Sometime during the Hellenistic period, the ancient harvest festival also became a day of renewing the Noahic covenant, described in Genesis 9:17, which is established between God and "all flesh that is upon the earth".[6] After the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE, offerings could no longer be brought to the Temple in Jerusalem and the focus of the festival shifted from agriculture to the Israelites receiving the Torah.[23]

By this time, some Jews were already living in the Diaspora. According to Acts 2:5–11 there were Jews from "every nation under heaven" in Jerusalem, possibly visiting the city as pilgrims during Pentecost.[24]

New Testament

editThe narrative in Acts 2 of the Pentecost includes numerous references to earlier biblical narratives like the Tower of Babel, and the flood and creation narratives from the Book of Genesis. It also includes references to certain theophanies, with certain emphasis on God's incarnate appearance on biblical Mount Sinai when the Ten Commandments were presented to Moses.[6] Theologian Stephen Wilson has described the narrative as "exceptionally obscure" and various points of disagreement persist among bible scholars.[26]

Some biblical commentators have sought to establish that the οἶκος ("house") given as the location of the events in Acts 2:2 was one of the thirty halls of the Temple where St. John's school is now placed (called οἶκοι), but the text itself is lacking in specific details. Richard C. H. Lenski and other scholars contend that the author of Acts could have chosen the word ἱερόν (sanctuary or temple) if this meaning were intended, rather than "house".[24][27] Some semantic details suggest that the "house" could be the "upper room" (ὑπερῷον) mentioned in Acts 1:12–26, but there is no literary evidence to confirm the location with certainty and it remains a subject of dispute amongst scholars.[6][24]

The events of Acts Chapter 2 are set against the backdrop of the celebration of Pentecost in Jerusalem. There are several major features to the Pentecost narrative presented in the second chapter of the Acts of the Apostles. The author begins by noting that the disciples of Jesus "were all together in one place" on the "day of Pentecost" (ἡμέρα τῆς Πεντηκοστῆς).[28] The verb used in Acts 2:1 to indicate the arrival of the day of Pentecost carries a connotation of fulfillment.[27][29][30]

There is a "mighty rushing wind" (wind is a common symbol for the Holy Spirit)[30][31] and "tongues as of fire" appear.[32] The gathered disciples were "filled with the Holy Spirit, and began to speak in other tongues as the Spirit gave them utterance".[33] Some scholars have interpreted the passage as a reference to the multitude of languages spoken by the gathered disciples,[34] while others have taken the reference to "tongues" (γλῶσσαι) to signify ecstatic speech.[26][35]

In Christian tradition, this event represents fulfillment of the promise that Christ will baptize his followers with the Holy Spirit.[27][36] Out of the four New Testament gospels, the distinction between baptism by water and the baptism by Christ with "Holy Spirit and fire" is only found in Matthew and Luke.[37][38]

The narrative in Acts evokes the symbolism of Jesus's baptism in the Jordan River, and the start of his ministry, by explicitly connecting the earlier prophecy of John the Baptist to the baptism of the disciples with the Holy Spirit on the day of Pentecost.[24][39] The timing of the narrative during the law giving festival of Pentecost symbolizes both continuity with the giving of the law, but also the central role of the Holy Spirit for the early church. The central role of Christ in Christian faith signified a fundamental theological separation from the traditional Jewish faith, which was grounded in the Torah and Mosaic Law.[24]

Peter's sermon in Acts 2:14–36 stresses the resurrection and exaltation.[9] In his sermon, Peter quotes Joel 2:28–32 and Psalm 16 to indicate that first Pentecost marks the start of the Messianic Age. About one hundred and twenty followers of Christ (Acts 1:15) were present, including the Twelve Apostles (Matthias was Judas's replacement) (Acts 1:13, 26), Jesus's mother Mary, other female disciples and his brothers (Acts 1:14). While those on whom the Spirit had descended were speaking in many languages, the Apostle Peter stood up with the eleven and proclaimed to the crowd that this event was the fulfillment of the prophecy.[40]

In Acts 2:17, it reads: "'And in the last days,' God says, 'I will pour out my spirit upon every sort of flesh, and your sons and your daughters will prophesy and your young men will see visions and your old men will dream dreams." He also mentions (Acts 2:15) that it was the third hour of the day (about 9:00 am). Acts 2:41 then reports: "Then they that gladly received his word were baptized: and the same day there were added unto them about three thousand souls."[41]

Some critical scholars believe some features of the narrative are theological constructions. They believe that even if the Pentecost narrative is not literally true, it does signify an important event in the history of the early church which enabled the rapid spread of Christianity. Within a few decades important congregations had been established in all major cities of the Roman Empire.[9]

Concerning Acts 2, Gerd Lüdemann considers the Pentecost gathering as very possible,[42] and the apostolic instruction to be historically credible.[43] Wedderburn acknowledges the possibility of a ‘mass ecstatic experience’,[44] and notes it is difficult to explain why early Christians later adopted this Jewish festival if there had not been an original Pentecost event as described in Acts.[45] He also holds the description of the early community in Acts 2 to be reliable.[46][47]

Lüdemann views Acts 3:1–4:31 as historical.[48] Wedderburn notes what he sees as features of an idealized description,[49] but nevertheless cautions against dismissing the record as unhistorical.[50] Hengel likewise insists that Luke described genuine historical events, even if he has idealized them.[51][52]

Biblical commentator Richard C. H. Lenski has noted that the use of the term "Pentecost" in Acts is a reference to the Jewish festival. He writes that a well-defined, distinct Christian celebration did not exist until later years, when Christians kept the name of "Pentecost" but began to calculate the date of the feast based on Easter rather than Passover.[27]

Peter stated that this event was the beginning of a continual outpouring that would be available to all believers from that point on, Jews and Gentiles alike.[53]

Liturgical celebration

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2018) |

Eastern churches

editIn the Eastern Orthodox Church, Pentecost is one of the Orthodox Great Feasts and is considered to be the highest ranking Great Feast of the Lord, second in rank only to Pascha (Easter). The service is celebrated with an All-night Vigil on the eve of the feast day, and the Divine Liturgy on the day of the feast itself. Orthodox churches are often decorated with greenery and flowers on this feast day, and the celebration is intentionally similar to the Jewish holiday of Shavuot, which celebrates the giving of the Mosaic Law. In the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, Pentecost is one of the seven Major "Lord's Feasts".

The feast itself lasts three days. The first day is known as "Trinity Sunday"; the second day is known as "Spirit Monday" (or "Monday of the Holy Spirit"); and the third day, Tuesday, is called the "Third Day of the Trinity."[54] The Afterfeast of Pentecost lasts for one week, during which fasting is not permitted, even on Wednesday and Friday. In the Orthodox Tradition, the liturgical color used at Pentecost is green, and the clergy and faithful carry flowers and green branches in their hands during the services.

All of the remaining days of the ecclesiastical year, until the preparation for the next Great Lent, are named for the day after Pentecost on which they occur. This is again counted inclusively, such that the 15th day of Pentecost is 14 days after Trinity Sunday. The exception is that the Melkite Greek Catholic Church marks Sundays "after Holy Cross".

The Orthodox icon of the feast depicts the Twelve Apostles seated in a semicircle (sometimes the Theotokos (Virgin Mary) is shown sitting in the center of them). At the top of the icon, the Holy Spirit, in the form of tongues of fire, is descending upon them. At the bottom is an allegorical figure, called Kosmos, which symbolizes the world. Although Kosmos is crowned with earthly glory he sits in the darkness caused by the ignorance of God.[citation needed] He is holding a towel on which have been placed 12 scrolls, representing the teaching of the Twelve Apostles.

Kneeling Prayer

editAn extraordinary service called the "Kneeling Prayer" is observed on the night of Pentecost. This is a Vespers service to which are added three sets of long poetical prayers, the composition of Basil the Great, during which everyone makes a full prostration, touching their foreheads to the floor (prostrations in church having been forbidden from the day of Pascha (Easter) up to this point). Uniquely, these prayers include a petition for all of those in hell, that they may be granted relief and even ultimate release from their confinement, if God deems this possible.[55] In the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, it is observed at the time of ninth hour (3:00 pm) on the Sunday of Pentecost.

Apostles' Fast

editThe Second Monday after Pentecost is the beginning of the Apostles' Fast (which continues until the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul on June 29). Theologically, Orthodox do not consider Pentecost to be the "birthday" of the church; they see the church as having existed before the creation of the world (cf. The Shepherd of Hermas).[56] In the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, the "Apostles Fast" has a fixed end date on the fifth of the Coptic month of Epip (which currently falls on July 12, which is equivalent to June 29, due to the current 13-day Julian-Gregorian calendar offset). The fifth of Epip is the commemoration of the Martyrdom of St. Peter and Paul.

Western churches

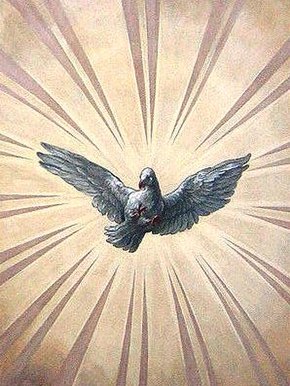

editThe liturgical celebrations of Pentecost in Western churches are as rich and varied as those in the East. The typical image of Pentecost in the West is that of the Virgin Mary seated centrally and prominently among the disciples with flames resting on the crowns of their heads. Occasionally, parting clouds suggesting the action of the "mighty wind";[57] rays of light and the Dove are also depicted. the Western iconographic style is less static and stylized than that of the East, and other very different representations have been produced, and, in some cases, have achieved great fame such as the Pentecosts by Titian, Giotto, and el Greco.

St. Paul already in the 1st century notes the importance of this festival to the early Christian communities: see: Acts 20:16 and 1 Corinthians 16:8. Since the lifetime of some who may have been eyewitnesses, annual celebrations of the descent of the Holy Spirit have been observed.

In the Roman Catholic liturgy, Pentecost marks the end and completion of the Easter season, and the birth or "great beginning" of the church.[58]

Before the Second Vatican Council Pentecost Monday as well was a Holy Day of Obligation[citation needed] during which the Catholic Church addressed the newly baptized and confirmed. Since the council, Pentecost Monday is no longer solemnized. Pentecost Monday remains an official festival in many Protestant churches, such as the (Lutheran) Church of Sweden, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland, and others. In the Byzantine Catholic Rite Pentecost Monday is no longer a Holy Day of Obligation, but rather a simple holiday. In the Extraordinary Form of the liturgy of the Roman Catholic Church, as at Easter, the liturgical rank of Monday and Tuesday of Pentecost week is a Double of the First Class[59] and across many Western denominations, Pentecost is celebrated with an octave culminating on Trinity Sunday. However, in the modern Roman Rite (Ordinary Form), Pentecost ends after Evening Prayer on the feast day itself, with Ordinary Time resuming the next day.

Marking the festival's importance, as the principal feast of the church and the fulfilment of Christ's purpose in coming into the world, namely bringing the Holy Spirit which had departed with Adam and Eve's fall, back into the world, all 33 following Sundays are "Sundays after Pentecost" in the Orthodox Church. In several denominations, such as the Lutheran, Episcopal, and United Methodist churches, and formerly in the Roman Catholic Church, all the Sundays from the holiday itself until Advent in late November or December are designated the 2nd, 3rd, etc. Sunday after Pentecost, again traditionally reckoned inclusively. Throughout the year, in Roman Catholic piety, Pentecost is the third of the Glorious Mysteries of the Holy Rosary, as well as being one of the Stations of the Resurrection or Via Lucis.

In some Evangelical and Pentecostal churches, where there is less emphasis on the liturgical year, Pentecost may still be one of the greatest celebrations in the year, such as in Germany or Romania. In other cases, Pentecost may be ignored as a holy day in these churches. In many evangelical churches in the United States, the secular holiday, Mother's Day, may be more celebrated than the biblical feast of Pentecost.[60] Some evangelicals and Pentecostals are observing the liturgical calendar and observe Pentecost as a day to teach the Gifts of the Holy Spirit.[clarification needed]

Across denominational lines Pentecost has been an opportunity for Christians to honor the role of the Holy Spirit in their lives, and celebrate the birth of the Christian Church in an ecumenical context.[61]

Red symbolism

editThe main sign of Pentecost in the West is the colour red. It symbolizes joy and the fire of the Holy Spirit.

Priests or ministers, and choirs wear red vestments, and in modern times, the custom has extended to the lay people of the congregation wearing red clothing in celebration as well. Red banners are often hung from walls or ceilings to symbolize the blowing of the "mighty wind"[57] and the free movement of the Spirit.[62]

In some cases, red fans, or red handkerchiefs, are distributed to the congregation to be waved during the procession, etc. Other congregations have incorporated the use of red balloons, signifying the "Birthday of the Church". These may be borne by the congregants, decorate the sanctuary, or released all at once.

Flowers, fruits, and branches

editThe celebrations may depict symbols of the Holy Spirit, such as the dove or flames, symbols of the church such as Noah's Ark and the Pomegranate, or especially within Protestant churches of Reformed and Evangelical traditions, words rather than images naming for example, the gifts and Fruits of the Spirit. Red flowers at the altar/preaching area, and red flowering plants such as geraniums around the church are also typical decorations for Pentecost masses/services.[63]

These symbolize the renewal of life, the coming of the warmth of summer, and the growth of the church at and from the first Pentecost.[63] In the southern hemisphere, for example, in southern Australia, Pentecost comes in the mellow autumntide, after the often great heat of summer, and the red leaves of the poinsettia have often been used to decorate churches then.

These flowers often play an important role in the ancestral rites, and other rites, of the particular congregation. For example, in both Protestant and Catholic churches, the plants brought in to decorate for the holiday may be each "sponsored" by individuals in memory of a particular loved one, or in honor of a living person on a significant occasion, such as their Confirmation day.[63]

In German-speaking and other Central European countries, and also in overseas congregations originating from these countries through migration, green branches are also traditionally used to decorate churches for Pentecost. Birch is the tree most typically associated with this practice in Europe, but other species are employed in different climates.[citation needed]

Lowering of doves

editIn the Middle Ages, cathedrals and great churches throughout Western Europe were fitted with a peculiar architectural feature known as a Holy Ghost hole: a small circular opening in the roof that symbolized the entrance of the Holy Spirit into the midst of the congregation. At Pentecost, these Holy Ghost holes would be decorated with flowers, and sometimes a dove figure lowered through into the church while the narrative of Pentecost was read. Holy Ghost holes can still be seen today in European churches such as Canterbury Cathedral.[64]

Similarly, a large two dimensional dove figure would be, and in some places still is, cut from wood, painted, and decorated with flowers, to be lowered over the congregation, particularly during the singing of the sequence hymn, or Veni Creator Spiritus. In other places, particularly Sicily and the Italian peninsula, rose petals were and are thrown from the galleries over the congregation, recalling the tongues of fire. (see below) In modern times, this practice has been revived, and adapted as well, to include the strewing of origami doves from above or suspending them, sometimes by the hundreds, from the ceiling.[65]

Hymns and music

editThe singing of Pentecost hymns is also central to the celebration in the Western tradition. Hymns such as Martin Luther's "Komm, Heiliger Geist, Herre Gott" (Come, Holy Spirit, God and Lord),[66][67] Charles Wesley's "Spirit of Faith Come Down"[68][69] and "Come Holy Ghost Our Hearts Inspire"[70] or Hildegard von Bingen's "O Holy Spirit Root of Life"[71][72] are popular. Some traditional hymns of Pentecost make reference not only to themes relating to the Holy Spirit or the church, but to folk customs connected to the holiday as well, such as the decorating with green branches.[73] Other hymns include "Oh that I had a Thousand Voices" ("O daß ich tausend Zungen hätte")[74][75] by German, Johann Mentzer Verse 2: "Ye forest leaves so green and tender, that dance for joy in summer air ..." or "O Day Full of Grace" ("Den signede Dag")[76] by Dane, N. F. S. Grundtvig verse 3: "Yea were every tree endowed with speech and every leaflet singing ...".

As Pentecost closes the Easter Season in the Roman Catholic Church, the dismissal with the double alleluia is sung at the end of Mass.[77] The Paschal Candle is removed from the sanctuary at the end of the day. In the Roman Catholic Church, Veni Sancte Spiritus is the sequence hymn for the Day of Pentecost. This has been translated into many languages and is sung in many denominations today. As an invocation of the Holy Spirit, Veni Creator Spiritus is sung during liturgical celebrations on the feast of Pentecost.[78][79]

Trumpeters or brass ensembles are often specially contracted to accompany singing and provide special music at Pentecost services, recalling the Sound of the mighty wind.[57] While this practice is common among a wide spectrum of Western denominations (Eastern Churches do not employ instrumental accompaniment in their worship) it is particularly typical, and distinctive to the heritage of the Moravian Church.[80]

Another custom is reading the appointed Scripture lessons in multiple foreign languages recounting the speaking in tongues recorded in Acts 2:4–12.[81]

Fasting and devotions

editFor some Protestants, the nine days between Ascension Day, and Pentecost are set aside as a time of fasting and universal prayer in honour of the disciples' time of prayer and unity awaiting the Holy Spirit. Similarly among Roman Catholics, special Pentecost novenas are prayed. The Pentecost Novena is considered the first novena, all other novenas prayed in preparation of various feasts deriving their practice from those original nine days of prayer observed by the disciples of Christ.

While the Eve of Pentecost was traditionally a day of fasting for Catholics, contemporary canon law no longer requires it. Both Catholics and Protestants may hold spiritual retreats, prayer vigils, and litanies in the days leading up to Pentecost. In some cases vigils on the Eve of Pentecost may last all night. Pentecost is also one of the occasions specially appointed for the Lutheran Litany to be sung.[82]

On the morning of Pentecost, a popular custom is "to ascend hill tops and mountains during the early dawn of Whitsunday to pray. People call this observance 'catching the Holy Ghost.' Thus they express in symbolic language the spiritual fact that only by means of prayer can the divine Dove be 'caught' and the graces of the Holy Spirit obtained."[83]

Another custom is for families to suspend "artfully carved and painted wooden doves, representing the Holy Spirit" over the dining tables as "a constant reminder for members of the family to venerate the Holy Spirit."[83] These are left hanging year-round and are cleaned before the feast of Pentecost, often being "encased in a globe of glass".[83]

On the vigil of Pentecost, a traditional custom is practiced, in which "flowers, fields, and fruit trees" are blessed.[83]

Sacraments

editFrom the early days of Western Christianity, Pentecost became one of the days set aside to celebrate Baptism. In Northern Europe Pentecost was preferred even over Easter for this rite, as the temperatures in late spring might be supposed to be more conducive to outdoor immersion as was then the practice. It is proposed that the term Whit Sunday derives from the custom of the newly baptized wearing white clothing, and from the white vestments worn by the clergy in English liturgical uses. The holiday was also one of the three days each year (along with Christmas and Easter) Roman Catholics were required to confess and receive Holy Communion in order to remain in good ecclesiastical standing.[84][failed verification]

Holy Communion is likewise often a feature of the Protestant observance of Pentecost as well. It is one of the relatively few Sundays some Reformed denominations may offer the communion meal, and is one of the days of the year specially appointed among Moravians for the celebration of their Love Feasts. Ordinations are celebrated across a wide array of Western denominations at Pentecost, or near to it. In some denominations, for example the Lutheran Church, even if an ordination or consecration of a deaconess is not celebrated on Pentecost, the liturgical color will invariably be red, and the theme of the service will be the Holy Spirit.

Above all, Pentecost is a day to hold Confirmation celebrations for youth. Flowers, the wearing of white robes or white dresses recalling Baptism, rites such as the laying on of hands, and vibrant singing play prominent roles on these joyous occasions, the blossoming of Spring forming an equal analogy with the blossoming of youth.

Rosalia

editA popular tradition arose in both west and east of decorating the church with roses on Pentecost, leading to a popular designation of Pentecost as Latin: Festa Rosalia or "Rose Feast"; in Greek this became ρουσάλια (rousália).[85] This led to Rusalii becoming the Romanian-language term for the feast, as well as the Neapolitan popular designation Pasca rusata ("rosey Easter").[citation needed] In modern times, the term in Greek refers to the eve of Pentecost, not Pentecost itself; or, in the case of Megara in Attica, to the Monday and Tuesday after Pascha,[86] as roses are often used during the whole liturgical season of the Pentecostarion, not just Pentecost. John Chrysostom warned his flock not to allow this custom to replace spiritually adorning themselves with virtue in reception of the Fruits of the Holy Spirit.[85]

Mariology

editA secular iconography in both Western and Eastern Churches reflects the belief of the presence of the Blessed Virgin Mary on the day of Pentecost and her central role in the divine concession of the gift of the Holy Spirit to the Apostles. Acts 1.14 confirms the presence of the Mother of Jesus with the Twelve in a spiritual communion of daily prayer. It is the unique reference to the Mother of God after Jesus's entrusting to John the Apostle during the Crucifixion.

According to that iconographic tradition, the Latin encyclical Mystici Corporis Christi officially stated:

She it was through her powerful prayers obtained that the spirit of our Divine Redeemer, already given on the Cross, should be bestowed, accompanied by miraculous gifts, on the newly founded Church at Pentecost; and finally, bearing with courage and confidence the tremendous burden of her sorrows and desolation, she, truly the Queen of Martyrs, more than all the faithful "filled up those things that are wanting of the sufferings of Christ...for His Body, which is the Church"; and she continues to have for the Mystical Body of Christ, born of the pierced Heart of the Savior, the same motherly care and ardent love with which she cherished and fed the Infant Jesus in the crib.

— Pope Pius XII, Mystici Corporis Christi, 2 March 1943[87]

The Catholic and the Orthodox Churches accord the Mother of God a special form of veneration called hyperdulia. It corresponds to the special power of intercessory prayers dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary over those of all saints. Popes have stated that Mary prayed to God and her intercession was capable to persuade God to send the Holy Spirit as a permanent gift to the Twelve and their successors, thus forming the Apostolic Church.

In a similar way, Pope John Paul II, in the general audience held in Vatican on May 28, 1997, affirmed:

Retracing the course of the Virgin Mary’s life, the Second Vatican Council recalls her presence in the community waiting for Pentecost. “But since it had pleased God not to manifest solemnly the mystery of the salvation of the human race before he would pour forth the Spirit promised by Christ, we see the Apostles before the day of Pentecost ‘persevering with one mind in prayer with the women and Mary the Mother of Jesus, and with his brethren’ (Acts 1:14), and we also see Mary by her prayers imploring the gift of the Spirit, who had already overshadowed her in the Annunciation” (Lumen gentium, n.59). The first community is the prelude to the birth of the Church; the Blessed Virgin’s presence helps to sketch her definitive features, a fruit of the gift of Pentecost. [...]

In contemplating Mary’s powerful intercession as she waits for the Holy Spirit, Christians of every age have frequently had recourse to her intercession on the long and tiring journey to salvation, in order to receive the gifts of the Paraclete in greater abundance. [...]

In the Church and for the Church, mindful of Jesus’s promise, she waits for Pentecost and implores a multiplicity of gifts for everyone, in accordance with each one's personality and mission.

— Pope John Paul II, General Audience, 28 May 1997, Rome[88]

The Marian intercessory prayer is dated to the day before Pentecost; while it is not explicitly stated that she was with the Apostles, it is in consideration of the fact she was called “full of grace” by the Archangel Gabriel at the Annunciation.

Mary’s special relationship with the Holy Spirit and her presence at Pentecost gave way to one of her devotional titles being “Mother of the Church”. In 2018 Pope Francis designated the Monday after Pentecost each year as the feast of Mary, Mother of the Church.

Music

editSeveral hymns were written and composed for Pentecost, the earliest in use today being Veni Creator Spiritus in (Come, Creator Spirit), attributed to the 9th-century Rabanus Maurus, and translated throughout the centuries in different languages.

This one and some more are suitable also for other occasions imploring the Holy Spirit, such as ordinations and coronations, as well as the beginning of school years.

Classical compositions

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2018) |

The Lutheran church of the Baroque observed three days of Pentecost. Some composers wrote sacred cantatas to be performed in the church services of these days. Johann Sebastian Bach composed several cantatas for Pentecost, including Erschallet, ihr Lieder, erklinget, ihr Saiten! BWV 172, in 1714 and Also hat Gott die Welt geliebt, BWV 68, in 1725. Gottfried Heinrich Stölzel wrote cantatas such as Werdet voll Geistes (Get full of spirit) in 1737.[89] Mozart composed an antiphon Veni Sancte Spiritus in 1768.

Gustav Mahler composed a setting of Maurus' hymn "Veni, Creator Spiritus" as the first part of his Symphony No. 8, premiered in 1910.

Olivier Messiaen composed an organ mass Messe de la Pentecôte in 1949/50. In 1964 Fritz Werner wrote an oratorio for Pentecost Veni, sancte spiritus (Come, Holy Spirit) on the sequence Veni Sancte Spiritus, and Jani Christou wrote Tongues of Fire, a Pentecost oratorio. Richard Hillert wrote a Motet for the Day of Pentecost for choir, vibraphone, and prepared electronic tape in 1969. Violeta Dinescu composed Pfingstoratorium, an oratorio for Pentecost for five soloists, mixed chorus and small orchestra in 1993. Daniel Elder's 21st century piece, "Factus est Repente", for a cappella choir, was premiered in 2013.

Regional customs and traditions

editIn Italy it was customary to scatter rose petals from the ceiling of the churches to recall the miracle of the fiery tongues; hence in Sicily and elsewhere in Italy, the feast is called Pasqua rosatum. The Italian name Pasqua rossa comes from the red colours of the vestments used on Whitsunday.[90]

In France it was customary to blow trumpets during Mass, to recall the sound of the mighty wind which accompanied the Descent of the Holy Spirit.[90]

In the northwest of England, church and chapel parades called Whit Walks take place at Whitsun (sometimes on Whit Friday, the Friday after Whitsun).[91] Typically, the parades contain brass bands and choirs; girls attending are dressed in white. Traditionally, Whit Fairs (sometimes called Whitsun Ales)[92] took place. Other customs such as morris dancing[93] and cheese rolling[94] are also associated with Whitsun.

In Hungary the day (called Pünkösd in Hungarian) is surrounded by many unique rites, which probably have their origins in ancient Hungarian customs. The girls dressed in festive costumes choose a Little Queen (Kiskirályné not to be confused with the Pünkösdi Királyné), who is raised high. Then a figure dressed as an animal appears and dies, and is brought back to life by his attendant chanting a joke incantation.[95]

In Finland there is a saying known virtually by everyone which translates as "if one has no sweetheart until Pentecost, he/she will not have it during the whole summer."[96]

In Port Vila, the capital of Vanuatu, people originating from Pentecost Island usually celebrate their island's name-day with a special church service followed by cultural events such as dancing.[citation needed]

In Ukraine the springtime feast day of Zeleni Sviata became associated with the Pentecost. (The exact origin of the relationship is not known). The customs for the festival were performed in the following order: first, home and hearth would be cleaned; second, foods were prepared for the festival; finally, homes and churches were decorated with wildflowers and various types of green herbs and plants. A seven course meal may have been served as the Pentecost feast which may have included traditional dishes such as cereal with honey (kolyvo), rice or millet grains with milk, sauerkraut soup (kapusniak), chicken broth with handmade noodles (yushka z zaterkoiu), cheese turnovers (pyrizhky z syrom), roast pork, buckwheat pancakes served with eggs and cheese (mlyntsi), and baked kasha.[97]

Date and public holiday

edit| Year | Western | Eastern |

|---|---|---|

| 2018 | May 20 | May 27 |

| 2019 | June 9 | June 16 |

| 2020 | May 31 | June 7 |

| 2021 | May 23 | June 20 |

| 2022 | June 5 | June 12 |

| 2023 | May 28 | June 4 |

| 2024 | May 19 | June 23 |

| 2025 | June 8 | |

| 2026 | May 24 | May 31 |

| 2027 | May 16 | June 20 |

| 2028 | June 4 | |

| 2029 | May 20 | May 27 |

| 2030 | June 9 | June 16 |

| 2031 | June 1 | |

| 2032 | May 16 | June 20 |

The earliest possible date is May 10 (as in 1818 and 2285). The latest possible date is June 13 (as in 1943 and 2038). The day of Pentecost is seven weeks after Easter Sunday: that is to say, the fiftieth day after Easter inclusive of Easter Sunday.[98] Pentecost may also refer to the 50 days from Easter to Pentecost Sunday inclusive of both.[99] Because Easter itself has no fixed date, this makes Pentecost a moveable feast.[100] In the United Kingdom, traditionally the next day, Whit Monday, was until 1970 a public holiday. Since 1971, by statute, the last Monday in May has been a Bank Holiday.

While Eastern Christianity treats Pentecost as the last day of Easter in its liturgies, in the Roman liturgy it is usually a separate feast.[101] The fifty days from Easter Sunday to Pentecost Sunday may also be called Eastertide.[101]

Since Pentecost itself is on a Sunday, it is automatically considered to be a public holiday in countries with large Christian denominations. However in Hungary, it is distinguished from a regular Sunday due to the stricter trading laws, forcing most businesses to close on even if they are normally open on Sundays (the same restrictions apply to the following Monday).[102]

Pentecost Monday is a public holiday in many countries including Andorra, Austria, Belgium, Benin, Cyprus, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Romania (since 2008), Senegal, (most parts of) Switzerland, Togo and Ukraine. It is also a public holiday in Catalonia, where it is known as la Segona Pasqua (Second Easter).[103]

In Sweden it was also a public holiday, but Pentecost Monday (Annandag Pingst) was replaced by Swedish National Day on June 6, by a government decision on December 15, 2004. In Italy and Malta, it is no longer a public holiday. It was a public holiday in Ireland until 1973, when it was replaced by Early Summer Holiday on the first Monday in June. In the United Kingdom the day is known as Whit Monday, and was a bank holiday until 1967 when it was replaced by the Spring Bank Holiday on the last Monday in May. In France, following reactions to the implementation of the Journée de solidarité envers les personnes âgées, Pentecost Monday has been reestablished as a regular (not as a working) holiday on May 3, 2005.[104]

Literary allusions

editAccording to legend, King Arthur always gathered all his knights at the round table for a feast and a quest on Pentecost:

So ever the king had a custom that at the feast of Pentecost in especial, afore other feasts in the year, he would not go that day to meat until he had heard or seen of a great marvel. [105]

German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe declared Pentecost "das liebliche Fest" – the lovely Feast, in a selection by the same name in his Reineke Fuchs.

- Pfingsten, das liebliche Fest, war gekommen;

- es grünten und blühten Feld und Wald;

- auf Hügeln und Höhn, in Büschen und Hecken

- Übten ein fröhliches Lied die neuermunterten Vögel;

- Jede Wiese sprosste von Blumen in duftenden Gründen,

- Festlich heiter glänzte der Himmel und farbig die Erde.[106]

"Pfingsten, das liebliche Fest", speaks of Pentecost as a time of greening and blooming in fields, woods, hills, mountains, bushes and hedges, of birds singing new songs, meadows sprouting fragrant flowers, and of festive sunshine gleaming from the skies and coloring the earth – iconic lines idealizing the Pentecost holidays in the German-speaking lands.

Further, Goethe records an old peasant proverb relating to Pentecost in his "Sankt-Rochus-Fest zu Bingen"[107] – Ripe strawberries at Pentecost mean a good wine crop.

Alexandre Dumas, père mentions of Pentecost in Twenty Years After (French: Vingt ans après), the sequel to The Three Musketeers. A meal is planned for the holiday, to which La Ramée, second in command of the prison, is invited, and by which contrivance, the Duke is able to escape. He speaks sarcastically of the festival to his jailor, foreshadowing his escape : "Now, what has Pentecost to do with me? Do you fear, say, that the Holy Ghost may come down in the form of fiery tongues and open the gates of my prison?"[108]

William Shakespeare mentions Pentecost in a line from Romeo and Juliet Act 1, Scene V. At the ball at his home, Capulet speaks in refuting an overestimate of the time elapsed since he last danced: "What, man? 'Tis not so much, 'tis not so much! 'Tis since the nuptial of Lucentio, Come Pentecost as quickly as it will, Some five-and-twenty years, and then we mask'd."[109] Note here the allusion to the tradition of mumming, Morris dancing and wedding celebrations at Pentecost.

"The Whitsun Weddings" is one of Philip Larkin's most famous poems, describing a train journey made through England on a Whitsun weekend.

See also

edit- Acts 2

- Pentecontad calendar

- Pentecost season

- Seven deacons (in Jerusalem and St. Philip in Azotus)

Notes

edit- ^ Deuteronomy 16:10

- ^ As part of the phrase ἐπ᾽ αὐτὴν ἔτους πεντηκοστοῦ καὶ ἑκατοστοῦ[12] (ep autēn etous pentēkastou kai hekatostou, "in the hundred and fiftieth year", or some variation of the phrase in combination with other numbers to define a precise number of years, and sometimes months. See: "... in the hundred and fiftieth year..." (1 Maccabees 6:20, KJV),[13] "In the hundred and one and fiftieth year..." (1 Maccabees 7:1, KJV),[14] " Also the first month of the hundred fifty and second year..." (1 Maccabees 9:3, KJV)[15] with other examples at 1 Maccabees 9:54 (KJV)[16] and 2 Maccabees 14:4 (KJV).[17][8]

References

edit- ^ Pritchard, Ray. "What Is Pentecost?". Christianity.com. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

According to the Old Testament, you would go to the day of the celebration of Firstfruits, and beginning with that day, you would count off 50 days. The fiftieth day would be the Day of Pentecost. So Firstfruits is the beginning of the barley harvest and Pentecost the celebration of the beginning of the wheat harvest. Since it was always 50 days after Firstfruits, and since 49 days equals seven weeks, it always came a 'week of weeks' later.

- ^ Acts 2:1–31

- ^ Acts 1:14

- ^ Exodus 34:22

- ^ a b Bratcher, Robert G; Hatton, Howard (2000). A handbook on Deuteronomy. New York: United Bible Societies. ISBN 978-0-8267-0104-6.

- ^ a b c d Jansen, John Frederick (1993). "Pentecost". In Metzger, Bruce M; Coogan, Michael D (eds.). The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195046458.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-504645-8. Retrieved 2018-12-02.

- ^ a b Danker, Frederick W; Arndt, William; Bauer, Walter (2000). A Greek-English lexicon of the New Testament and other early Christian literature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-03933-6.

- ^ a b c Gerhard, Kittel; Friedrich, Gerhard; Bromiley, Geoffrey William, eds. (2006). "Pentecost". Theological dictionary of the New Testament. Translated by Geoffrey William Bromiley. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2243-7.

- ^ a b c Bromiley, Geoffrey William, ed. (2009). "Pentecost". The International standard Bible encyclopedia (2 ed.). Grand Rapids, Michigan: W.B. Eerdmans.

- ^ Tobit 2:12 Maccabees 12:32

- ^ Leviticus 25:10

- ^ "Septuagint (LXX), 1 Maccabees 6:20". academic-bible.com: The Scholarly Portal of the German Bible Society. German Bible Society. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ 1 Maccabees 6:20

- ^ 1 Maccabees 7:1

- ^ 1 Maccabees 9:3

- ^ 1 Maccabees 9:54

- ^ 2 Maccabees 14:4

- ^ Balz, Horst Robert; Schneider, Gerhard (1994). Exegetical dictionary of the New Testament. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2803-3.

- ^ a b Keil, Carl Friedrich; Delitzsch, Franz (2011). Commentary on the Old Testament. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers. ISBN 978-0-913573-88-4.

- ^ a b Gaebelein, Frank E (1984). The expositors Bible commentary with the New International Version of the Holy Bible in twelve volum. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-36500-6.

- ^ Mishnah Arakhin 7:1–9:8; Tosefta Arakhin 5:1–19; Babylonian Talmud Arakhin 24a–34a.

- ^ NIV archaeological study Bible an illustrated walk through biblical history and culture : New International Version. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan. 2005. ISBN 978-0-310-92605-4.

- ^ "Shavuot - The Holiday of the Giving of the Torah - Chabad.org". chabad.org.

- ^ a b c d e Longenecker, Richard N. (2017). Acts. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-53203-3.

- ^ Maʻoz, Moshe; Nusseibeh, Sari (2000). Jerusalem: Points Beyond Friction, and Beyond. Brill. ISBN 978-90-411-8843-4.

- ^ a b Gilbert, Gary (2002). "The List of Nations in Acts 2: Roman Propaganda and the Lukan Response". Journal of Biblical Literature. 121 (3): 497–529. doi:10.2307/3268158. ISSN 0021-9231. JSTOR 3268158.

- ^ a b c d Lenski, R. C. H. (2008). Commentary on the New Testament: The Interpretation of the Acts of the Apostles 1-14. Augsburg Fortress. ISBN 978-1-4514-1677-0.

- ^ Acts 2:1

- ^ Vine, W. E. (2003). Vine's Expository Dictionary of the Old & New Testament Words. Thomas Nelson Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-7852-5054-8.

- ^ a b Calvin, John. Commentary on Acts – Volume 1 – Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved 2018-12-02.

- ^ Acts 2:2

- ^ Acts 2:3

- ^ Acts 2:4

- ^ Acts 2:6–11

- ^ 1 Corinthians 14

- ^ Acts 1:5, John 14:16–17

- ^ Luke 3:16

- ^ Expositor's Bible Commentary

- ^ Acts 1:5, Acts 11:16

- ^ Joel 2:28–29

- ^ Acts 2:41

- ^ ‘Although doubting that the specification "Pentecost" belongs to the tradition, Lüdemann supposes, on the basis of references to glossolalia in Paul's letters and the ecstatic prophecy of Philip's daughters (Acts 21:9), that "we may certainly regard a happening of the kind described by the tradition behind vv.1–4 as very possible."’, Lüdemann quoted by Matthews, ‘Acts and the History of the Earliest Jerusalem Church’, in Cameron & Miller (eds.), ‘Redescribing Christian origins’, p. 166 (2004)

- ^ ‘"The instruction by the apostles is also to be accepted as historical, since in the early period of the Jerusalem community the apostles had a leading role. So Paul can speak of those who were apostles before him (in Jerusalem!, Gal. 1.17)" (40.)’, Lüdemann quoted by Matthews, ‘Acts and the History of the Earliest Jerusalem Church’, in Cameron & Miller (eds.), ‘Redescribing Christian origins’, p. 166 (2004).

- ^ ‘It is also possible that at some point of time, though not necessarily on this day, some mass ecstatic experience took place.’, Wedderburn, ‘A History of the First Christians’, p. 26 (2004).

- ^ ‘At any rate, as Weiser and Jervell point out,39 it needs to be explained why early Christians adopted Pentecost as one of their festivals, assuming that the Acts account was not reason enough.’, Wedderburn, ‘A History of the First Christians’, p. 27 (2004).

- ^ ‘Many features of them are too intrinsically probable to be lightly dismissed as the invention of the author. It is, for instance, highly probable that the earliest community was taught by the apostles (2:42)—at least by them among others.’, Wedderburn, ‘A History of the First Christians’, p. 30 (2004).

- ^ ‘Again, if communal meals had played an important part in Jesus’ ministry and had indeed served then as a demonstration of the inclusive nature of God’s kingly rule, then it is only to be expected that such meals would continue to form a prominent part of the life of his followers (Acts 2:42, 46), even if they and their symbolic and theological importance were a theme particularly dear to ‘Luke’s’ heart.47 It is equally probable that such meals took place, indeed had to take place, in private houses or in a private house (2:46) and that this community was therefore dependent, as the Pauline churches would be at a later stage, upon the generosity of at least one member or sympathizer who had a house in Jerusalem which could be placed at the disposal of the group. At the same time it might seem unnecessary to deny another feature of the account in Acts, namely that the first followers of Jesus also attended the worship of the Temple (2:46; 3:1; 5:21, 25, 42), even if they also used the opportunity of their visits to the shrine to spread their message among their fellow-worshippers. For without question they would have felt themselves to be still part of Israel.’, Wedderburn, ‘A History of the First Christians’, p. 30 (2004).

- ^ "Despite what is in other respects the negative result of the historical analysis of the tradition in Acts 3–4:31, the question remains whether Luke's general knowledge of this period of the earliest community is of historical value. We should probably answer this in the affirmative, because his description of the conflict between the earliest community and the priestly nobility rests on correct historical assumptions. For the missionary activity of the earliest community in Jerusalem not long after the crucifixion of Jesus may have alarmed Sadducean circles... so that they might at least have prompted considerations about action against the Jesus community.", Lüdemann quoted by Matthews, ‘Acts and the History of the Earliest Jerusalem Church’, in Cameron & Miller (eds.), ‘Redescribing Christian origins’, pp. 168–169 (2004).

- ^ ‘The presence of such idealizing features does not mean, however, that these accounts are worthless or offer no information about the earliest Christian community in Jerusalem.46 Many features of them are too intrinsically probable to be lightly dismissed as the invention of the author.’, Wedderburn, ‘A History of the First Christians’, p. 30 (2004).

- ^ ‘At the same time it might seem unnecessary to deny another feature of the account in Acts, namely that the first followers of Jesus also attended the worship of the Temple (2:46; 3:1; 5:21, 25, 42), even if they also used the opportunity of their visits to the shrine to spread their message among their fellow-worshippers. For without question they would have felt themselves to be still part of Israel.48 The earliest community was entirely a Jewish one; even if Acts 2:5 reflects an earlier tradition which spoke of an ethnically mixed audience at Pentecost,49 it is clear that for the author of Acts only Jewish hearers come in question at this stage and on this point he was in all probability correct.’, Wedderburn, ‘A History of the First Christians’, p. 30 (2004).

- ^ ‘There is a historical occasion behind the description of the story of Pentecost in Acts and Peter's preaching, even if Luke has depicted them with relative freedom.’, Hengel & Schwemer, 'Paul Between Damascus and Antioch: the unknown years', p. 28 (1997).

- ^ ‘Luke's ideal, stained-glass depiction in Acts 2–5 thus has a very real background, in which events followed one another rapidly and certainly were much more turbulent than Acts portrays them.’, Hengel & Schwemer, 'Paul Between Damascus and Antioch: the unknown years', p. 29 (1997).

- ^ Acts 2:39

- ^ All troparia and kontakia · All lives of saints. "Trinity Week – 3rd Day of the Trinity". Ocafs.oca.org. Retrieved 2013-12-21.

- ^ Pentecost – Prayers of Kneeling Archived 2013-11-02 at the Wayback Machine. See the third prayer.

- ^ Patrologia Graecae, 35:1108–9.

- ^ a b c Acts 2:2

- ^ Preface of Pentecost, The New Sunday Missal: Texts approved for use in England and Wales, Ireland, Scotland and Africa, Geoffrey Chapman, 1982, p. 444

- ^ "Catholic Encyclopedia: Pentecost". Newadvent.org. 1912-10-01. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ^ "Pentecost: All About Pentecost (Whitsunday)!". ChurchYear.net. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ^ "Pentecost Picnic 2009". Themint.org.uk. Retrieved 2010-05-17. [permanent dead link]

- ^ John 3:8

- ^ a b c "St. Catherine of Sweden Roman Catholic Church – Bulletin". StCatherineofSweden.org. Archived from the original on 2009-08-29. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ^ "Seeing red, and other symbols of Pentecost - On The Way e-zine". www.ontheway.us. May 2012. Archived from the original on 2021-12-28. Retrieved 2021-12-02.

In the Middle Ages, cathedrals and great churches were built with a peculiar architectural feature called the Holy Ghost hole, a small portal in the roof through which the Holy Spirit could descend to reside among the assembled worshippers. As part of the Pentecost celebration, the hole was adorned with flowers and often a lowly servant on the cathedral roof would lower the figure of a dove through the roof into the nave of the church while the Acts account of Pentecost was read. England's Canterbury Cathedral, Mother Church of the Anglican Communion, is one church where a Holy Ghost hole can be seen today.

- ^ "The Episcopal Church and Visual Arts". Ecva.org. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ^ "200–299 TLH Hymns". Lutheran-hymnal.com. Archived from the original on 2020-08-13. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ^ "Come, Holy Ghost, God and Lord". Lutheran-hymnal.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-14. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ^ "HymnSite.com's Suggested Hymns for the Day of Pentecost (Year C)". Hymnsite.com. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ^ "Spirit of Faith, Come Down". Hymntime.com. Retrieved 2010-05-17. [permanent dead link]

- ^ "Come, Holy Ghost, Our Hearts Inspire". Hymntime.com. Retrieved 2010-05-17. [permanent dead link]

- ^ "O Holy Spirit, Root of Life". Hymnsite.com. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ^ "Texts > O Holy Spirit, root of life". Hymnary.org. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ^ "Hymns and Hymnwriters of Denmark | Christian Classics Ethereal Library". Hymnary.com. 2009-08-11. Archived from the original on 2021-12-28. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ^ "O That I Had a Thousand Voices". Hymntime.com. Retrieved 2010-05-17. [permanent dead link]

- ^ "O daß ich tausend Zungen hätte gospel christian songs free mp3 midi download". Ingeb.org. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ^ "Lutheran Worship Online Hymnal – section MO". Lutheranhymnal.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-14. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-07-26. Retrieved 2017-05-31.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Rhabanus Maurus". Hymntime.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-12. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ^ "Catholic Encyclopedia: Veni Creator Spiritus". Newadvent.org. 1912-10-01. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ^ "Moravian Music Foundation". MoravianMusic.org. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ^ Nelson, Gertrud Muller (1986). To Dance With God: Family Ritual and Community Celebration. Paulist Press. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-8091-2812-9. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ^ (P. Drews.). "Litany". Ccel.org. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ^ a b c d Weiser, Francis X. (1956). The Holyday Book. Harcourt, Brace and Company. pp. 44–45.

- ^ "Catholic Encyclopedia: Frequent Communion". Newadvent.org. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ^ a b "Byzantine Catholics and the Feast Of Pentecost: "Your good Spirit shall lead me into the land of righteousness. Alleluia, Alleluia, Alleluia!"". archpitt.org. Byzantine Catholic Archdiocese of Pittsburgh. 2015-12-28. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ "ρουσάλια" [rousalia]. Enacademic.com – Greek Dictionary (in Greek).

- ^ Pope Pius XII (March 2, 1943). "Encyclical "Mystici Corporis Christi"". Holy See. Libreria Editrice Vaticana.

- ^ "General audience of Wednestay 28 May 1997". Holy See. Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Archived from the original on August 30, 2020.

- ^ Cantatas for Pentecost Archived 2011-06-29 at the Wayback Machine review of the 2002 recording by Johan van Veen, 2005

- ^ a b Kellner, Karl Adam Heinrich (May 11, 1908). "Heortology; a history of the Christian festivals from their origin to the present day". London, K. Paul, Trench, Trübner & co., limited – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Whit Friday: Whit Walks". Whitfriday.brassbands.saddleworth.org. 2011-06-18. Archived from the original on 2008-05-09. Retrieved 2013-12-21.

- ^ "'Feasts and Festivals': 23 May: Whitsun Ales". Feastsandfestivals.blogspot.com. 2010-05-23. Retrieved 2013-12-21.

- ^ "Foresters Morris Men". www.cs.nott.ac.uk. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011.

- ^ "Cheese Rolling". BBC. 30 May 2005. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2013..

- ^ Dömötör, Tekla (1972). Magyar Népszokások (in Hungarian) (2nd ed.). Budapest: Corvina. p. 11. ISBN 9631301788.

- ^ "Did You Ever Wonder... about Pentecost Traditions?". Trinity Lutheran Church. Retrieved 2019-06-17.

- ^ Farley, Marta Pisetska (1990). "Pentecost". Festive Ukrainian Cooking. University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 78–84. doi:10.2307/j.ctt7zwbs9.11. ISBN 978-0-8229-3646-6. JSTOR j.ctt7zwbs9.11.

- ^ "Pentecost". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2017-07-11. Retrieved 2017-06-03.

Pentecost... major festival in the Christian church, celebrated on the Sunday that falls on the 50th day after Easter.

- ^ Taft, Robert (2005). "Pentecost". In Kazhdan Alexander P (ed.). Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6. Archived from the original on 2017-08-10. Retrieved 2017-06-07.

- ^ Grassie, William (2013-03-28). "Easter: A Moveable Feast". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 2017-04-13. Retrieved 2017-06-04.

- ^ a b Presbyterian Church (US) (1992). Liturgical Year: The Worship of God. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-25350-9.[page needed]

- ^ "Vasárnap, hétfőn nem lesz bolt!". 18 May 2024. Retrieved 2024-05-18.

- ^ "¿Qué se celebra por la Segunda Pascua?". www.barcelona.cat (in Spanish). 2023-05-24. Retrieved 2024-05-07.

- ^ "Décision du Conseil d'Etat". Archived from the original on 2009-05-28. Retrieved 2009-11-05.

- ^ Le Morte d'Arthur, Thomas Malory. Book 7, chapter 1 Archived 2010-01-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Das Gedicht Pfingsten, das liebliche Fest... von Johann Wolfgang von Goethe". gedichte-fuer-alle-faelle.de.

- ^ "Nachrichten – Kultur". Projekt Gutenberg.spiegel.de. 2009-08-17. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ^ "Nachrichten – Kultur". Projekt Gutenberg.spiegel.de. 2009-08-17. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ^ "Romeo and Juliet Text and Translation – Act I, Scene V". Enotes.com. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

External links

edit- Pentecost on RE:Quest Archived 2012-04-19 at the Wayback Machine

- A collection of 22 prayers for Pentecost

- "Pentecost" article from the Catholic Encyclopedia

- "Pentecost" article from the Jewish Encyclopedia

- Feast of Pentecost Greek Orthodox Archdiocese

- Explanation of the Feast from the Handbook for Church Servers (Nastolnaya Kniga) by Sergei V. Bulgakov

- The Main Event: The Church Takes Center Stage from Mcdonough | Eagle's Landing First Baptist Church Eagle's Landing First Baptist Church in McDonough, Georgia.